United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

no tickets required; ages 11 and up.

Could the United States have stopped the Holocaust? The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum attempts to answer this question with its newest exhibit, “Americans and the Holocaust,” which explores the country’s response to Nazism.

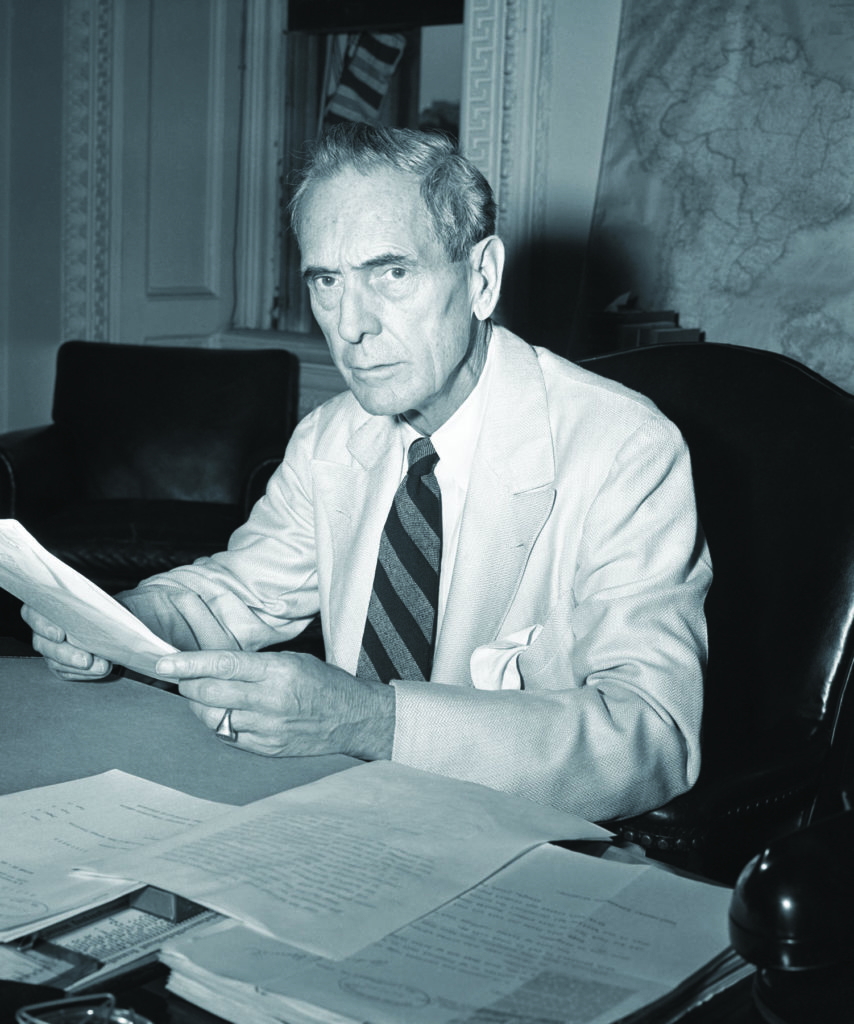

Following the rise of Hitler, many Jews in Germany attempted to seek refuge in the States. But when they arrived by ship at American ports, restrictive immigration policies implemented by Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long turned them away.

Long, who supervised the State Department’s visa division, cited national security concerns in actively seeking to reduce the number of Jewish refugees immigrating to the States. Long—and many Americans—believed the fleeing refugees could include spies or saboteurs. To suppress aid and rescue efforts, he deliberately misrepresented records of U.S. refugee acceptance numbers and even stifled incoming reports to Washington about the mass murder of Jews in Europe.

Beyond Long’s sabotage, “Americans and the Holocaust” highlights evidence of American apathy and racism toward not only Jews but African and Asian Americans within its own borders—including legalized segregation, Jim Crow laws, and Japanese American internment—as well as indifference to news reports of the Nazis’ increasingly violent anti-Semitic rule.

Through interconnecting rooms, visitors can explore a timeline of historical displays featuring coverage of Nazism through American newpapers, newsreels, and film that evidence the mounting pressure for Washington to respond as Hitler’s bloody campaign peaked. Each section contains interactive displays, photos, videos, documents, and short documentaries on wartime views of Nazism.

As news headlines spotlighted Nazi Germany’s ill-treatment of its own citizens throughout the 1930s, the Roosevelt administration stayed uncomfortably silent. One possible reason for that is shown in a display of a 1938 poll revealing that two-thirds of Americans believed that German Jews were either “entirely” or “partly” to blame for their own persecution.

While the museum unmasks the reasons for Washington’s silence, it also provokes questions about why Roosevelt, despite early knowledge of Germany’s atrocities, took no action, and why Americans remained skeptical even when confronted with reports of the death camps. Can America be held responsible? “The United States alone could not have prevented the Holocaust,” the museum’s website explains, “but more could have been done to save some of the six million Jews who were killed.”

In trying to provide an overview of complex answers to complex questions, “Americans and the Holocaust” uncovers the unpleasant truth of what happens when those with the power to help fail to reach out to the most vulnerable of our earthly population.

This review was originally published in the October 2018 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.