Time hasn’t erased a massacre’s haunting images

I visited the hamlet of My Lai, in the village of Son My, Vietnam, on March 16, 2018—the 50th anniversary of an American infantry company’s shameful massacre of unarmed civilians. Led by 2nd Lt. William L. Calley Jr. and Capt. Ernest L. Medina, about 100 men of the 23rd Infantry Division (Americal) entered the village and killed nearly everyone there. Hundreds died—347, the U.S. Army’s official number; 504, according to the Vietnamese government’s list of people killed. Even pigs, chickens and water buffaloes were “wasted,” in the GI slang of the era. Why?

Supposedly the Americans were frustrated by the casualties they were taking in firefights with an enemy they couldn’t see, and My Lai was to make up for their loses. Because of those frustrations, they brutally gunned down innocent, helpless, defenseless women (some pregnant), children and old men.

As I walked the grounds of what was once a peaceful agricultural village along the coast of South Vietnam and now is a memorial, many sights haunted me. The memorial includes a re-creation of the 1968 village with most of the huts depicted as they looked after the Americans left—burned to the ground—but one hut shows how a home might have looked before the shooting started.

Entering the hut, my mind flashed back 50 years to when I was an 18-year-old infantryman in Vietnam. Although I wasn’t at the massacre, most Vietnamese huts I saw were built in the same fashion: straw-matted roofs held up by wooden poles, dirt floors, walls of dirt or bamboo, and a few pieces of wooden furniture and clay pots strewn about. On the outside, farming utensils hung from the side of a pen holding cattle or water buffalo, if the family was lucky enough to own any.

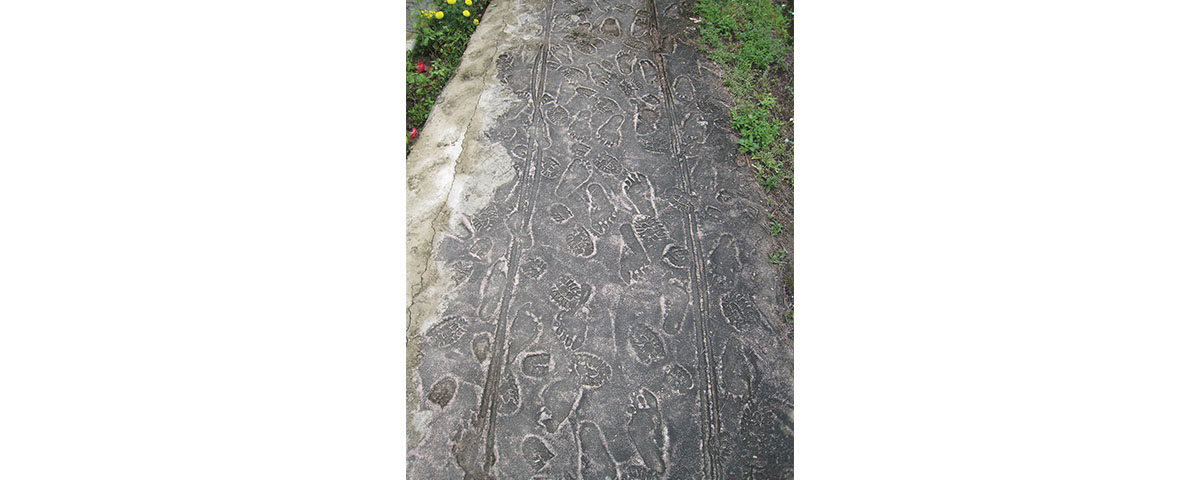

But of all the sounds and sights and smells I encountered at the memorial, one vision haunted me the most, indelibly etched in my brain—the footprints.

The re-creator of My Lai turned the original muddy footpaths into concrete walkways pocked with images of footprints pressed into the concrete. Footprints of children, mothers and old men are surrounded by the boot marks of soldiers who dragged them to their deaths. The path along the irrigation ditch where 170 villagers were systematically shot dead, shocked me the most as I looked down and saw hundreds of footprints in the mud, mostly small bare feet.

I was riveted. What could have been, if those Vietnamese lives had not been snuffed out at such a young age? What was going through their minds as they were thrown into a ditch to be slaughtered with such savagery? We’ll never know.

But I also thought of the American soldiers. What was going through their minds as they were committing these dreadful acts? Were they just “following orders?” Or were they willing participants? Probably both.

But once again, why? How could one human commit such savagery upon another?

A possible answer is training. During basic training and advanced infantry training we were taught that we would fight a people who were subhuman: Our cadre of instructors often used terms such as gooks, dinks and slopeheads. Devaluing the lives of our enemy made it easier for us to kill them.

Even Gen. William Westmoreland, commanding general of all U.S. forces in South Vietnam, conveyed this demeaning attitude. “The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does a Westerner,” he said in a 1974 documentary film, Hearts and Minds. “Life is plentiful. Life is cheap in the Orient.”

When I heard Westmoreland make that remark, I recalled a well-publicized photo of a Vietnamese father standing beside an American armored vehicle, holding his lifeless child in his arms, looking up at the GIs and pleading for help. That image didn’t jive with Westmoreland’s cavalier remarks.

The horrors that American soldiers inflicted at My Lai certainly represent the U.S. Army’s most abysmal failure of leadership at all levels during the war.

But each of us is responsible for our own “moral compass.” What happened to that when we went to Vietnam? Did we leave it at home?

The waste of all those lives at My Lai cannot be rectified. Nothing can undo those tragic, gruesome killings. How does one live with himself after committing such egregious acts?

When I walked through the front gate of My Lai on the solemn anniversary of the shootings, I was shocked to see so many people there, mostly Vietnamese, but also a few Westerners. Though it was a sad, reflective day, I saw a lot of smiles and witnessed many warm greetings. I was no more than 100 feet past the main gate when something unexpected happened. An elderly Vietnamese gentleman approached me, took my hands in his, looked deep into my eyes and mumbled a few words. I didn’t know the words he was speaking, but I could understand what he was saying. He was thanking me for coming to the memorial—and forgiving me for the senseless act of violence. As the kind man walked away, another held my hand and squeezed tightly, saying a few soft, gentle words.

The younger generation was much more gregarious. Kids approached me with big smiles on their faces. They spoke in English and wanted to have pictures taken with me. Initially, I was a little embarrassed. We were there for a somber occasion, and I didn’t want attention focused on me. But then I remembered that time goes on, and the young were born decades after the My Lai massacre. So I attempted to blend my presence with respect, reverence and a bit of good public relations by speaking with the children and discreetly posing for their photographs.

After several hours, I left My Lai—but the image of those ghostly footprints kept nagging at me. The poor bare feet. What pain they must have suffered. What cruelty. And the boot marks of the soldiers. Fifty years have passed, but the few short hours in March 1968 will linger forever in the minds of those soldiers who left their boot marks on the village of My Lai.

Michael H. Cunningham served in Vietnam June 1968-March 1969 with Company C, 1st Battalion, 46th Infantry Regiment, 198th Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division (Americal). He is a retired U.S. Customs official and the author of Walking Point: An Infantryman’s Untold Story.

Do you have reflections on the war that you would like to share? Email your idea or article to Vietnam@HistoryNet.com, subject line: Reflections.