Facts, information and articles about The Mountain Meadows Massacre, an event of Westward Expansion from the Wild West

The Mountain Meadows Massacre Facts

Dates

September 7-11, 1857

Location

Mountain Meadows, Utah

Casualties

100-140

Mountain Meadows Massacre Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about The Mountain Meadows Massacre

» See all The Mountain Meadows Massacre Articles

The Mountain Meadows Massacre summary: A series of attacks was staged on the Baker-Fancher wagon train around Mountain Meadows in Utah. This massive slaughter claimed nearly everyone in the party from Arkansas and is the event referred to as the Mountain Meadows Massacre. They were headed toward California and their path took them through the territory of Utah.

The wagon train made it through Utah during a period in time of violence history would later call the Utah War to rest in the area of Mountain meadows. It was leaders from the nearby militia called Nauvoo Legion that staged the attack on the train of pioneers. This militia was comprised of the Mormons that settled Utah. With the intent of pointing the finger at Native Americans they armed Southern Paiute Native Americans and coerced them to join their party in the attack.

The first attack resulted in a siege of five days with the wagon travelers fighting back. After the siege both sides were growing desperate. The travelers were running low on food and water and the militia feared that they would be recognized for not being Native Americans and therefore complicate the war in Utah. As a group of militia men entered the camp under a white flag, they then lead the emigrants from their encampment to their death. The death total was 120 and comprised of men, women and children. They did spare the lives of 17 children who were younger than seven. They quickly buried all the bodies and their haste left the slightly exposed.

Articles Featuring The Mountain Meadows Massacre From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

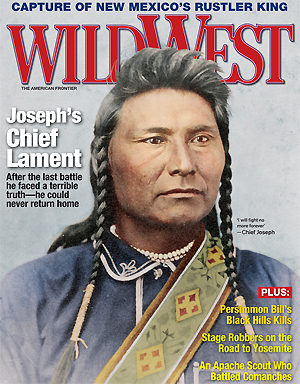

Wild West: The Legacy of Mountain Meadows

At dawn on Monday, September 7, 1857, Major John D. Lee of the Nauvoo Legion, Utah’s territorial militia, led a ragtag band of 60 or 70 Latter-day Saints, better known as Mormons, and a few Indian freebooters in an assault on a wagon train from Arkansas.

The emigrants, now known to history as the Fancher Party, were camped at Mountain Meadows, an alpine oasis on the wagon road between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. The party, led by veteran plainsmen familiar with the California Trail and its variants, consisted of a dozen large, prosperous families and their hired hands. The wagon train comprised 18 to 30 wagons pulled by ox and mule teams, plus several hundred cattle and a number of blooded horses the men were driving to California’s Central Valley. The company included about 140 men, women and children—the women and children outnumbered the able-bodied men 2-to-1.

As daylight broke in the remote Utah Territory valley, a volley of gunfire and a shower of arrows ripped into the wagon camp from nearby ravines and hilltops, immediately killing or wounding about a quarter of the adult males. The surviving men of the Fancher Party leveled their lethal long rifles at their hidden, painted attackers and stopped the brief frontal assault in its tracks. The Arkansans pulled their scattered wagons into a circle l and quickly improved their wagon fort, digging a pit to protect the women and children from stray projectiles. Cut off from any source of water and under continual gunfire, the emigrants fended off their assailants for five long, hellish days.

On Friday, September 11, hope appeared in the form of a white flag. The emigrants let the emissary, a Mormon from a nearby settlement, into their fort, and then John D. Lee, the local Indian agent, followed. Lee told the Arkansans he and his men had come to rescue them from the Indians. If the emigrants would lay down their arms, the local militia would escort them to safety. The travelers had few options: they surrendered and agreed to Lee’s strange terms.

The Mormons separated the survivors into three groups: the wounded and youngest children led the way in two wagons; the women and older children walked behind; and the men, each escorted by an armed guard, brought up the rear. Lee led this forlorn parade more than a mile to the California Trail and the rim of the Great Basin. There, the senior Mormon officer escorting the men gave an order: perhaps “Halt!” but by most accounts, “Do your duty!” A single shot rang out, and each escort turned and shot his man. Painted savages—a few of whom may have been actual Indians—jumped out of the oak brush lining the trail and cut down the women and children, while Lee directed the murder of the wounded. Within five minutes, the atrocity was over. Everyone was dead except for 17 orphans, all under the age of 7, whom the killers deemed too young to be credible witnesses and who qualified as “innocent blood” under Mormon doctrine.

For the men who committed this horrific atrocity, the legacy of Mountain Meadows became a haunting memory they could never escape. Those most guilty of the crime explained it with denials, lies and alibis that twisted and turned as the evidence inevitably came out. Some of the killers went mad, some apparently killed themselves and several fled to Mexico, but only one man faced the music and was executed for the crime: John D. Lee, regarded as a scapegoat by his descendants and historians alike. For the children who survived and the families of the victims, the massacre became a deep and enduring wound. The murderers appropriated the Fancher train’s considerable property and cash. Much of it apparently made its way into Mormon leader Brigham Young’s pockets, and not a penny of compensation was ever offered to the survivors. For many living descendants and relatives of the victims, who have long been slandered as frontier hard cases who got what they deserved, the massacre remains a bitter injustice.

For today’s Latter-day Saints, Mountain Meadows is the most troubling event in their religion’s complicated history. There is nothing like it in the faith’s history of suffering, sacrifice and devotion. For 150 years, leaders and official historians of the LDS Church have worked hard to justify or explain away the crime, and a large part of the legacy of the murders is a tangled web of lies and deception.

On Tuesday, September 11, 2007, another wagon train from Arkansas will arrive at Mountain Meadows to commemorate the sesquicentennial of one of the grimmest anniversaries in American history. After a long forgetfulness, the last five years have seen a flurry of histories, biographies, novels, plays, films and articles about the massacre. Academic presses are primed to release at least three serious nonfiction studies of the event over the next year, including one by the forensic anthropologist who analyzed the bones of 28 men, women and children the U.S. Army buried in 1859. Despite the passage of 150 years, it appears that Latter-day Saints, survivors of the Southern Paiute Nation, descendants of the victims and their murderers, and a scattering of historians and the curious will gather at the meadows. They will wrestle with the complicated legacy of what all agree was an atrocity and some view as America’s first act of religious terrorism.

I’ll be there, too, as I have been for about every other September 11 over the last 20 years. During that time, I’ve witnessed the dedication of two monuments—one near the highway on Dan’s Hill overlooking the killing ground, where a 1990 granite monument financed by descendants and the state of Utah honors the victims; and a second that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints raised in 1999 over the grave of the victims, whose remains were inadvertently unearthed by a backhoe during the monument’s hurried construction. Ironically, the cairn standing at the center of the second memorial is modeled after the “rude monument, conical in form and 50 feet in circumference at the base and 12 feet in height,” that Brevet Major James Henry Carlton’s 1st Dragoons raised in 1859 and Brigham Young directed his minions to destroy two years later. I’ve met grandsons and great-great-great-great grandsons of the men who committed the crime—members of the Lee, Klingensmith, Johnson, Knight, Adair, Pearce, Haight, Higbee, Wilden and Bateman families—all of whom still live under the shadow cast by their ancestors’ act 150 years ago. I’ve encountered even more descendants of the Baker, Cameron, Dunlap, Fancher, Jones, Miller, Mitchell, Prewit and Tackitt families who lost loved ones at the meadows. I admire and respect almost every one, and I have come to love more than a few of them.

I’m also the author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows, which took five years to write; and editor (with David L. Bigler) of Innocent Blood: Essential Narratives of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which took another five years to assemble and should appear next year from the Arthur H. Clark Company. I have a dog in this fight and make no pretensions to being a disinterested party: I happily admit I’ll be fascinated to witness whatever drama plays out at Mountain Meadows late this summer. I am also intrigued by the massacre’s strange legacy and a little astonished to find myself as enmeshed in the awful tale and its ongoing story as was its greatest chronicler, southern Utah historian Juanita Brooks. Like Brooks, I am amazed to find myself slandered, libeled, reviled, hated and even feared for simply following the evidence to its obvious conclusions.

An Incident That Should Be Forgotten: Books

At first glance, it seems incredible that the largest massacre of American citizens in the history of the Oregon and California trails is practically forgotten. Again and again, I’ve had people ask, “Why haven’t I ever heard about this?” Upon consideration, the atrocity’s obscurity is easier to understand: After all, such a tale of blood and sorrow had little to recommend it to those who created the legend of the West. It involved white people killing white people in an act of treachery that does nothing to support our pride in what makes us Westerners. Since the story involved a persecuted religion, historians liked to navigate around it. Latter-day Saints, the people with the biggest stake in the story, long tried to blame it on someone else, anyone else—the victims, the Indians, a single evil fanatic and now, it appears, a whole bunch of fanatics. The bloody tale gave them no comfort whatsoever, and they were happy to see it disappear into the mists of time.

Josiah Gibbs, author of the 1909 book Lights and Shadows of Mormonism, recalled that “a prominent Salt Lake editor” said, “The Mountain Meadows massacre is an incident that should be forgotten,” for the sake of peace in Utah. Yet events surrounding the upcoming sesquicentennial appear primed to bring more attention to the massacre than it has had since the death of Brigham Young.

A surprising number of books, both fiction and nonfiction, have dealt with the massacre during the last five years. They form part of a long tradition: Writers as renowned as Mark Twain and Jack London told the story, and Buffalo Bill Cody rescued his sister May from the massacre in a play that helped launch his career. Amanda Bean’s The Fancher Train won the Western Writers of America’s Spur Award for best novel of the West in 1958, and Danièle Desgranges published Autopsie D’un Massacre: Mountain Meadows in Paris in 1990.

My personal favorite among all the recent books on the massacre is Judith Freeman’s Red Water, which brilliantly reconstructs the lives of three of the wives of John D. Lee. Freeman’s novel transports the reader to a very different time and place: the ragged edge of the Mormon frontier in southern Utah. Unlike historical novelists who simply dress up contemporary characters in funny clothes and put them in quaint places where they encounter famous dead people, Freeman re-creates the alien world of Deseret, where men like Major/Judge/President John Lee held simultaneous power as military officers and legal and religious authorities. Historians operate by strict and often restricting rules, but Freeman’s use of imagination to re-create the past offers perceptions that I often found jarring—and enlightening.

Mountain Meadows fiction keeps appearing, and though most of it is awful, Elizabeth Crook’s The Night Journal, in which the main character’s father is an orphan of the massacre, won the Western Writers of America Spur Award this year for best long novel. Mainstream publishers released two nonfiction works in 2003 that dealt with the atrocity. Alfred A. Knopf published Sally Denton’s study of the killings in American Massacre: The Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, September 1857. Denton is a talented writer, but Mormon historians found her book an easy target. Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith was more successful. His study of modern polygamy and violence provoked such a strong denunciation from Richard Turley, the managing director of the LDS Church’s Family and Church History Department, that Mormon outrage helped propel the book onto bestseller lists for months. (Insiders speculate that Doubleday’s publicity department tore up their promotion plans when the attack appeared on the church’s Web site two weeks before its release: Their work was done.)

Burying the Past: Movies

A surprising hero of the Mountain Meadows wars of the last two decades is Gordon B. Hinckley, who became president, prophet, seer and revelator of the LDS Church in 1995 after effectively running the organization since the early 1980s. When descendants began to lobby to build a monument to the victims of the massacre in the late 1980s, their efforts went nowhere until they enlisted President Hinckley’s support. Once he was on board, powerful southern Utah politicians co-opted the project and eventually claimed credit for the whole idea. The descendants, however, knew the truth and were grateful for Hinckley’s help. At a meeting in 1989, they asked how they could reward his good efforts. Hinckley asked only one favor: “No movies.”

It was a typically astute request from a man who had spent his life working on public relations for the LDS Church. The institution had successfully kept the story off screens both big and little for decades. After The Mountain Meadows Massacre hit the silent silver screen in 1912, almost a century passed before another major film appeared. The church itself shot down several attempts to make a movie about the massacre. Warner Brothers (and later, rumor has it, Paramount) optioned the rights to turn Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre into a movie—despite historian Dale L. Morgan qualifying it as “the least likely candidate for a movie among the books published in 1950.” Powerful Mormon political and financial figures put an end to the project. Following the success of Roots, the 1977 ABC television miniseries, David Susskind hoped to create a similar phenomenon with a series on the massacre. The epic had scheduled production when CBS cancelled it.

As Hinckley surely knew, his hope that no one would ever make a film about Mountain Meadows was wishful thinking. The Arts & Entertainment Channel had already shown an episode on the murders as part of Kenny Rogers’ Real West series. Noted Mormon historian Leonard Arrington served as the main talking head, and the episode relied heavily on legends about “Missouri Wildcats” and other evil emigrant fantasies, with similar blame assigned to the terrifying Southern Paiutes, who in Mormon legend forced the righteous settlers to kill the emigrants.

Along the same lines, Dixie State College cinema professor Eric Young, a descendant of Brigham Young’s brother, made another film in southern Utah in 2000. Based on Juanita Brooks’ study, the documentary is a classic LDS retelling of the story with lots of blame for the victims and the Indians, but it won two “Telly” local television awards. Young became interested in the subject when he tried to date a descendant of John D. Lee. Her mother told him bluntly that because of what Brigham Young did to her ancestor, she wouldn’t let him date her daughter. Ironically, Professor Young “said he made the film with the aim of clearing Brigham Young of responsibility for the massacre, but was unable to find the evidence to do so.”

Bill Kurtis’ Investigating History produced an episode for the History Channel in 2004 about the murders from University of New Mexico professor Paul Hutton’s script. It incorporated Hutton’s updated research and focused largely on the 1859 federal investigation of the atrocity. The channel’s Standards and Practices Committee, which had never objected to any of Kurtis’ productions, took an intense interest in the Mountain Meadows episode. The final script (which won a Spur Award) bore only a passing resemblance to Hutton’s original.

Another film professor, Brian Patrick of the University of Utah, released a more compelling documentary in 2004, Burying the Past: Legacy of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. (I’m one of several historians Patrick interviewed.) Patrick became interested in the story after reading a news article about the reestablishment of the Mountain Meadows Association. It had regrouped in 1998 to prod the state of Utah into restoring the monument at Dan Sill Hill after the granite slab listing the victims toppled over due to poor construction, weather conditions or an earthquake, take your pick. A newspaper story about the association’s attempts at reconciliation among those who share the massacre’s legacy caught his attention. During the five years Patrick spent making the film, the story evolved as the LDS Church dedicated the second monument, and different factions and personalities came into conflict. (The accidental discovery of their ancestors’ grave, and secretly shipping the bones to Brigham Young University for analysis, offended many of the victims’ descendants.) Ultimately, the film dealt not only with reconciliation but—as its title reveals—the difficulty of dealing with the darker side of Mormon history.

Patrick’s film did very well on the independent film festival circuit and garnered 11 awards, but he was unable to persuade PBS to broadcast it and his documentary found no national distributor. It did attract media attention when Spudfest, the fledgling film festival founded by actress Dawn Wells (Mary Ann of Gilligan’s Island), pulled the documentary from its lineup, claiming the film was too violent for a family-oriented event. Patrick heard a different story: local Mormon authorities were up in arms, he told a reporter, claiming “the film is hateful and mean-spirited, and they don’t want their people to see it and, if [Spudfest] is going to show it, there’s going to be big trouble.”

Bigger trouble was brewing. Every LDS public relations flak’s nightmare arrived this June with the release of September Dawn, director Christopher Cain’s romantic telling of the awful tale and the first feature-length film ever made about the massacre (see review in June 2007 Wild West). Cain, best known to Western buffs as the director of Young Guns, financed the project himself and shot it in British Columbia. He added a melodramatic love story to a born-again script by Carole Whang Schutter. Cain assembled a stellar cast, including Terence Stamp, Jon Voight and Lolita Davidovich. Cain’s son Dean (best known as Superman in Lois and Clark) put in a brief appearance as Mormon prophet Joseph Smith. Trent Ford and Tamara Hope gave solid performances as the conflicted Mormon hero and his doomed love. But Terence Stamp created a terrifying vision of Brigham Young, while sticking to dialogue drawn from the religious leader’s fire-and-brimstone sermons and legal statements. Jon Voight, as Bishop Jacob Samuelson, has generated fear and loathing in Mormon country. Latter-day Saints who saw advance screenings objected to the film’s “stereotypical, one-dimensional portrait of blindly obedient church members that bordered on cartoonish at times.” A brief scene showing a frontier version of the sacred Mormon temple ceremony was especially sensitive.

As I write this, how the public will react to September Dawn is an open question. In early May 2007 I attended a preview showing the day after the broadcast of Helen Whitney’s PBS documentary The Mormons, which included a long and powerful segment on Mountain Meadows. (I presented the case that Brigham Young did it, while LDS historian Glen Leonard argued he didn’t.) September Dawn’s producers invited to the viewing more than 100 descendants and relatives of those killed in the massacre, and seeing the film with them was an honor. If nothing else, the movie will introduce millions of people to this forgotten stain on America’s history—and most importantly, it should doom forever attempts to blame the disaster on its victims.

Whodunit? A Case of Vengeance and Retribution

A single question lurks behind almost everything ever written about the Mountain Meadows Massacre: Did Brigham Young order it, and if so why? Predicting how someone will come down on the issue is not hard: “It’s a story I’ve lived with my entire life, being a so-called gentile in Salt Lake City,” rare book dealer Ken Sanders said. “No faithful, believing Mormon will ever accept that Brigham Young had anything to do with the Mountain Meadows Massacre.” At the same time, Sanders is certain no non-Mormon “will ever believe otherwise.”

Attempts to vindicate the Mormon prophet have been underway since news of the murders reached California in early October 1857. It was filtered through Mormon representatives at San Bernardino before the story appeared in the Los Angeles Star. These spin doctors fooled no one. The statements the paper gathered from emigrants with the wagon trains following the Fancher Party “distinctly charge, that this persecution and murder of the emigrants is promoted by the Mormon leaders, [and] that opposition to the Federal Government is the cause of it.” A mass meeting of concerned citizens in Los Angeles on October 12, 1857, denounced the “long, undisturbed, systemized [sic] course of thefts, robberies, and murders, promoted and sanctioned by their leader, and head prophet, Brigham Young, together with the Elders and followers of the Mormon Church, upon American citizens, who necessity has compelled to pass through their Territory.”

I believe Mountain Meadows was a calculated act of vengeance directed and carried out by Brigham Young and his top associates. The Mormon prophet himself viewed the murders that way. Nine days after the massacre, his interpreter, Dimick Huntington, told Ute leader Arapeen in Young’s presence, “Josephs Blood had got to be Avenged.” Why was this particular train the target of prophetic wrath? The answer was no mystery to the editor who first published the news in California. “A general belief pervades the public mind here that the Indians were instigated to this crime by the ‘Destroying Angels’ of the church,” the Los Angeles Star concluded on October 10, less than a month after the slaughter, “and that the blow fell on these emigrants from Arkansas, in retribution of the death of Parley Pratt, which took place in that State.” Brigham Young’s resolute suppression of the truth about the atrocity for almost 20 years and the fact that he sheltered and protected all the perpetrators (except John D. Lee) who could have “put the saddle on the right horse,” supports this conclusion.

The LDS Church presented its first systematic alibi for the massacre in 1884. It claimed Brigham Young issued orders intended to prevent the massacre and remained blissfully ignorant about what happened due to the lies of southern Utah leaders. Such an interpretation is based on an impossibility—that devout frontier Mormon authorities believed they could deceive Brigham Young. “I am watching you,” he said in an 1855 sermon printed in the territory’s only newspaper. “Do you know that I have my threads strung all through the Territory, that I may know what individuals do?” John D. Lee was the newspaper’s agent for Iron County that year, but as a key element in the prophet’s internal intelligence network, Young’s boast would hardly have surprised Lee.

Brigham Young, while serving as both Utah’s governor and Indian superintendent in 1857, never raised a finger to find out what happened or recover the wagon train’s property from the murderers. Four months after the massacre, in his official report of the largest slaughter of American emigrants in the history of the Oregon, California and Mormon trails, Young charged the Arkansans in the wagon train had murdered four Indians with poison. “This conduct so enraged the Indians that they immediately took measures for revenge.” The evildoers fell victim to “the natural consequences of that fatal policy which treats Indians like wolves or other ferocious beasts.” For 13 years, Young insisted Mormons had nothing to do with the massacre: Indians killed the emigrants, who simply got what they deserved.

Powerful men can obstruct justice or try to suppress the truth for a variety of reasons, but personal guilt drives most coverups. Several Mormon historians have made recent attempts to refute Juanita Brooks’ conclusion that “Brigham Young was accessory after the fact, in that he knew what happened, and how and why it happened.” Their efforts seem unwise, especially since Brooks observed, “Evidence of this [Young’s involvement] is abundant and unmistakable, and from the most impeccable Mormon sources.” But Mormon historians as distinguished as Thomas Alexander now insist that Brigham Young investigated the massacre repeatedly over 15 years yet somehow never figured out whodunit. This newly imagined creation, Brigham as Mr. Magoo, might sell in Utah Valley, but elsewhere it will probably not fare well. Young knew the names of the Mormons who participated in the wholesale atrocities, Robert Glass Cleland and Juanita Brooks concluded 51 years ago. “Brigham Young was not a credulous simpleton: he was not duped or hoodwinked: he was not misinformed.”

When historians confront a complex historical event, they try to develop an interpretation that provides the simplest explanation of the evidence—a task complicated when evidence is destroyed, manufactured and relies on testimony of young children or men with blood on their hands. After writing Blood of the Prophets and Innocent Blood, I believe the atrocity is best explained as a calculated act of vengeance. It was not retribution, which is the just application of punishment for a bad act, but revenge, which simply involves getting even and is not particular about who gets the ax.

In May 1861, after destroying the monument the U.S. Army raised over the graves of the victims in 1859, Young told Lee that those “used up at the Mountain Meadowes were the Fathers, Mothe[rs], Bros., Sisters & connections of those that Muerders the Prophets; they Merittd their fate, & the only thing that ever troubled him was the lives of the Women & children, but that under the circumstances [this] could not be avoided.” Lee’s story is difficult to challenge, since a Mormon apostle confirmed the quote that he ascribed to the prophet: “When he came to the Monument that contained their Bones, he made this remark, Vengence is Mine Saith the Lord, & I have taken a litle of it.”

Coverups Never Ending

Yet another battle in the ongoing war over how the story of Mountain Meadows will be told may begin soon. Mormon historians Richard Turley, Ronald Walker and Glen Leonard claim Oxford University Press will release their opus, Tragedy at Mountain Meadows, next year. They have been making the same claim every year for the last five years, but give them credit: They’ve got their story and they’re sticking to it. This is not, lead author Turley insists, an “official” history, despite the fact that the LDS Church has seemingly spent millions of dollars subsidizing the project.

Since the book has not appeared, it would be unfair to judge a pig in a poke, but a “press release” handed out at the book’s 2002 announcement—“Forthcoming in 2003 from Oxford University Press!”—has me waiting on the edge of my seat. “Tragedy at Mountain Meadows takes a fresh look at one of Mormon history’s most controversial topics,” it promises. The work will be drawn “from documents previously not available to researchers.” Like me, I suppose, although sources at the church’s historical department have told friends “Bagley got everything of significance” at LDS Archives. Ah well, “this spell-binding narrative offers fascinating conclusions on why Mormon settlers in isolated southern Utah deceived the emigrant party with a promise of safety and killed the adults and all but a few of the youngest children.”

I would not want to be among those “Mormon settlers in isolated southern Utah” right about now. I’m always eager to read a spellbinding narrative, especially when written by a committee, but the announcement’s last sentence leaves me cold: “Tragedy at Mountain Meadows offers the definitive account of a dark chapter in American history.” Generally it’s best to wait till you’ve written a book before proclaiming it definitive, and even better to leave it to someone else to make that proclamation. “The word ‘definitive’ is often overused,” historian Brigham D. Madsen wrote in his review of Blood of the Prophets in The Western Historical Quarterly. “This account of the killings merits that distinction.”

What will happen this September 11 when another Arkansan wagon train rolls into Mountain Meadows? As of June, the rumor mill is already working overtime with hints of possible breakthroughs on a number of contentious fronts. For years, relatives of the victims and friends of the site have watched in disbelief as the St. George megalopolis has begun to fill up the once-open rangeland at the Meadows with vacation homes and McMansions. For most of a decade, friends of the place have lobbied against long odds to secure federal protection and administration of this contested ground as a National Historic Park Site (or Monument). Those odds would change dramatically if the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints agreed that what its prophet has called “sacred ground” deserves the protection of the American people.

Readers can learn about plans for the 150th anniversary at the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation Web site at http://1857massacre.com/MMM/mmmf.htm. For a Mormon perspective on the September 1857 event, see www.mormonwiki.com/mormonism/Mountain_Meadows_massacre.

This article was written by Will Bagley and originally published in the October 2007 issue of Wild West Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Wild West magazine today!

Featured Article

Wild West: Rescue of the Mountain Meadows Orphans

In the fall of 1857, a party of emigrants from Arkansas camped in southern Utah Territory at Mountain Meadows, a lush alpine oasis on the Spanish Trail where wagon trains rested before crossing the Mojave Desert. The party was made up of about a dozen large, prosperous families and their hiredhands, driving about 18 wagons and several hundred cattle to Southern California.Of its 135 to 140 members, almost 100 were women and children.

As the travelers brewed coffee not long after dawn on Monday, September 7, a volley of gunfire suddenly tore into them from nearby ravines and hilltops, immediately killing or wounding about a quarter of the able-bodied men. The survivors quickly pulled their scattered wagons into a corral and leveled their lethal long rifles at their hidden, painted attackers, stopping a brief frontal assault in its tracks. The Arkansans quickly built a wagon fort and dug a pit at its center to protect the women and children. Cut off from water and under continual gunfire,the emigrants fended off their assailants for five long, hellish days.

Finally, on Friday, September 11, hope appeared in the form of a white flag. The emigrants let the emissary, a Mormon from the nearby settlement of Cedar City, into their fort, and then the local Indian agent, John D. Lee, entered the camp. Lee told them the Indians had gone, and if the Arkansans would lay down their arms, he and his men would escort them to safety. The desperate emigrants, Deputy U.S. Marshal William Rogers reported two years later, trusted Lee’s honor and agreed to his unusual terms. They separated into three groups—the wounded and youngest children, who led the way in two wagons; the women and older children, who walked behind; and then the men, each escorted by an armed member of the Nauvoo Legion, the local militia. The surviving men cheered their rescuers when they fell in with their escort.

Lee led his charges three-quarters of a mile from the campground to a southern branch of the California Trail. As the odd parade approached the rim of the Great Basin, a single shot rang out, followed by an order: “Do your duty!” The escorts turned and shot down the men, painted “Indians” jumped out of oak brush and cut down the women and children, and Lee directed the murder of the wounded. Within five minutes, the most brutal act of religious terrorism in America history was over—and itwould not be surpassed until a bright September morning exactly 144 years later, as airplanes filled with passengers were flown into the Pentagon and New York City’s World Trade Center.

So ended the Mountain Meadows Massacre—but the story of this mass murder and its twisted legacy had only begun. Although “white men did most of the killing,” as participant Nephi Johnson later admitted, Utah Indian Superintendent Brigham Young informed Washington that “Capt. Fancher & Co. fell victims to the Indians’ wrath” and blamed the emigrants for “indiscriminately shooting and poisoning them”—essentially, Young argued, they got what they deserved. Young made no effort to investigate the crime or identify the perpetrators. The murderer—smany of whom stripped for battle and donned war paint to look like Indians—took a blood oath to blame the slaughter on the local Paiutes (see “Warriors and Chiefs” in this issue), and since they thought they had killed everyoneold enough to tell the emigrants’side of the story, whocould contradict them?

The killers, however, made a mistake: They spared 17 of the children, believing they would be too young to be credible witnesses. Mormon doctrine made shedding innocent blood an unforgivable sin, and anyone under the age of 8 was by definition “innocent blood.” Lee later claimed he was ordered to spare only children“who were so young theycould not talk.” The Mormonsactually killed at least half adozen children 8 years old oryounger, but in an atrocitynotably lacking in mercy, thatbelief in not shedding innocentblood saved the lives of 10 girls and sevenboys between infancy and age 6.

Yet their youth did not prevent the orphans from leaving behind some of the most compelling accounts of what actually happened on that black Friday. “The scenes and incidents of the massacre were so terrible that they were indelibly stamped on my mind, notwithstanding I was so young at the time,” Nancy Huff Cates recalled in 1875. The tale of how a hard-bitten crew of colorful frontiersmen rescued these sad orphans is one of the great, untold stories of the American West.

The first news of the worst massacre in the history of the Oregon and California trails appeared in the Los Angeles Star on October 3, 1857. Several children, it reported, “were picked up on the ground, and were being conveyed to San Bernardino.” A week later, that newspaper said the Indians saved 15 “infant children” and sold them to the Mormons at Cedar City. By the end of the year, word of the murders had reached the families of the victims in northwest Arkansas, where an angry citizen asked if the government would send enough men to Utah “to hang all the scoundrels and thieves at once, and give them the same play they give our women and children?”

William C. Mitchell’s married daughter, Nancy Dunlap, had been with the so-called Fancher party, as had a married son, Charles, and an unmarried son, Joel. Mitchell wrote to Senator W.K. Sebastian, chairman of the Committee on Indian Affairs, expressing his hope that an infant grandson had survived. He asked Sebastian to investigate: “I must have satisfaction for the inhuman manner in which they have slain my children,” he wrote,“together with two brothers-in-law and seventeenof their children.” Many of the murdered emigrantscame from powerful Arkansas families. InFebruary 1858, the “deeply aggrieved” people ofCarroll County in northwest Arkansas petitioned Congress to appropriate funds to reclaim andreturn the children saved from the massacre.

Utah was still in a virtual state of rebellion, however, and not long after the massacre Mormon guerrillas had burned Army supply trains on the way to the territory. The government could do nothing much until June 1858, after Brigham Young’s hoped-for alliance with the Indians collapsed and the “Mormon Revolt” fizzled. Young grudgingly accepted a blanket pardon for treason and allowed the new governor and federal judges into the territory. That same month the U.S. Army established the nation’s largest military station at Camp Floyd, 40 miles from Salt Lake City. Alfred Cumming replaced Young as governor, and Jacob Forney took over as Indian superintendent. One of their first priorities was to locate the Mountain Meadows orphans and “use every effort to get possession” of them, as Washington had first orderedForney to do back in March.

Jacob Hamblin, the president of the Mormon Southern Indian Mission, met with Brigham Young in June and told Young “everything” about the murders, including that whites were involved. Young told him, “Don’t say anything about it,” and Hamblin loyally continued to blame the massacre on the Indians. Hamblin told Forney that 15 of the survivors were living near his ranch with white families. With considerable effort, Hamblin claimed, the children had been “recovered, bought and otherwise, from the Indians.” Forney hoped to go south in a month to recover the children, but he put off the job for almost a year, although he didtell Hamblin to collect the children.

In early August, Young sent orders to Isaac Haight and William Dame, religious leaders in southern Utah (and the same men who had given the direct orders to massacre the Arkansans). He told them to have Hamblin“gather up those children that were saved from theIndian Masacre [sic].” Forney also sent orders toHamblin, “All the children must be secured, at anycost or sacrifice, whether among whites or Indians.” He instructed Hamblin to take the childreninto his family. “You will be well compensated forall the trouble you and Mrs. Hamblin will have,”Forney promised.

Hamblin had found 15 of the orphans by December 1858, but he was “satisfied that there were seventeen of them saved from the massacre,” he wrote. He claimed two children had been taken east by the Paiutes, a story apparently concocted to extort government money to pay imaginary ransoms to the Indians. In late January 1859, Forney reported to Washington that he had recovered 17 children (when in fact he had seen none of them), and in March he finally headed south on this errand. Meanwhile, Congress had appropriated$10,000 to locate the survivors of Mountain Meadowsand transport them back to Arkansas.

Not long after setting out, Forney learned that $30,000 worth of property and presumably some cash had been distributed among Mormon church officials at Cedar City within a few days of the massacre. He reported that he hoped to recover at least some of the stolen property. He stopped 40 miles south of Salt Lake City to testify before the grand jury that the fearless Judge John Cradlebaugh was holding in Provo. Forney had aligned himself with the federal officials led by Governor Cumming who had aligned themselves—and sometimes lined their pockets—with Brigham Young’s interests. Forney and Cumming were timid men, and as heavy drinkers both were easily intimidated. Events soon showed that neither of them had the courage to ensure justice was done for the victims of the massacre, let alone the gumption to stand up to a powerhouse like Brigham Young, “the Lion of the Lord.” Despite detailed, credible evidence that whites and not Indians had committed themassacre, Forney hired Mormons to escort him on his trip to southern Utah.

At Nephi, Forney met up with two remarkable frontiersmen: Colonel William Rogers and Captain James Lynch. Rogers, affectionately known as “Uncle Billy” in both California and Carson Valley, was already a Western legend in 1858 when hemoved to Salt Lake City, opened the CaliforniaHouse (a hotel “fitted up in superior style”) andquickly won a legion of friends. Two years later,British explorer Richard Burton found ColonelRogers running the Pony Express station at RubyValley, trading furs and managing a governmentIndian farm for the Western Shoshones. Rogerswas already a veteran of many “adventures amongthe whites and reds,” Burton said, and had “manya hairbreadth escape to relate.” But nothing he didin his long, colorful career was as dangerous as hismission to Mountain Meadows.

Uncle Billy joined Forney at Nephi as an assistant. At the same time, Captain Lynch was leading a party of between 25 and 40 men south from Camp Floyd, where he had worked for the commissary department, to the area that would become Arizona (possibly to prospect there), when he too met Forney at Nephi.

Born in Ireland, Lynch had been orphaned not long after his parents immigrated to Brooklyn, and he had drifted to New Orleans, where he enlisted in the frontier army. Lynch had served under Zachary Taylor and Robert E. Lee in the Mexican War and was cited three times for bravery. (Lynch’s captain title, however, was honorary, not military.) After his discharge, he joined the Utah Expedition as a civilian, but years later he recalled he resigned in disgust at “the continual failure of the soldiers to rescue the orphaned children.”

Forney told Lynch he was “doubtful” about the Mormons he had hired to escort him to Mountain Meadows. When Lynch reached Beaver in late March, he found the Mormons had indeed abandoned Forney, warning that if he pressed on “the people down there would make an eunuch of him.” Forney asked for help, and Lynch placed his whole party at his command, but he expressed concern that Forney had hired Mormons in the first place, “the very confederates of these monsters, who had so wantonly murdered unoffending emigrants, to ferret out the guilty parties.” It would not be the last doubt Lynch would have about thenervous Indian superintendent.

Forney’s party tried to get information as they trekked south, reaching Cedar City on April 16. “But no one professed to have any knowledge of the massacre, ” Rogers recalled, “except that they had heard itwas done by the Indians.” Jacob Hamblin sent IraHatch, a talented Indian interpreter who hadprobably killed at least one of the Arkansans himself,to guide the men to the scene of the massacre.

“Words cannot describe the horrible picture which was here presented to us,” James Lynch wrote a few months after the mid-April visit to the massacre site. What he and the others saw in this beautiful alpine valley would haunt them to their graves: “Human skeletons, disjointed bones, ghastly skulls and the hair of women were scattered in frightful profusion over a distance of two miles.” The men found three mounds, evidence of “the careless attempt that had been made to bury the unfortunate victims.” In a ravine by the side of the road, “a large number of leg and arm bones, and also skulls, could be seen sticking above the surface, as if they had been buried there,” Rogers reported. They spent several hours burying a few of the exposed remains. “When I first passed through the place,” Rogers later wrote, “I could walk for near a mile on bones, and skulls laying grinning at you, and women and children’s hair in bunches as big as a bushel.” The bones of children were lying by those of grown persons, “as if parent and child had met death at the same instant and with the same stroke.” Lynch could not forget seeing the remains of those innocent victims of“avarice, fanatacism and cruelty,” adding, “I have witnessed many harrowing sights on the fields of battle, but never did my heart thrill with such horrible emotions.”

The day after visiting Mountain Meadows, Forney and his escort reached the Mormon settlement at Santa Clara, where they found 13 of the surviving children in the custody of Hamblin, who was just beginning his legendary career as a frontiersman and Indian interpreter for explorers such as John Wesley Powell. In his recollections, Lynch claimed he and a few men might have been sent ahead in disguise to find the children and determine what kind of reception awaited Forney. Fifty years later, Lynch remembered that Hamblin claimed some of the children were being held captive by the Indians. “Produce them or we will kill you,” Lynch recalled saying while pistols and rifles were pointed at Hamblin’s head. “He surrendered.” (It’s a wonderful story, but none of the contemporary reports— including that by Lynch—tell it.) After Forney arrived, the men spent three days at Santa Clara while clothing was made forthe children.

Eyewitnesses gave contradictory reports about the circumstances of the rescued children.“The children when we firstsaw them were in a mostwretched and deplorable condition,” James Lynch charged,“with little or no clothing, coveredwith fillth and dirt, theypresented a sight heart-rendingand miserable in the extreme.”U.S. Army Major James Carletonsaid their captors “keptthese little ones barely alive.”In contrast, William Rogersreported that all the childrenhad sore eyes but were otherwisewell, and Jacob Forneybelieved the children were wellcared for. He found them“happy and contented, exceptthose who were sick” andinsisted the orphans were inbetter condition than most ofthe children in the settlementsin which they lived.

Forney rejected a number of obviously fraudulent claims to repay ransoms allegedly paid to save the children, since it was well known that the children “did not live among the Indians one hour.” He received other claims for the children’s support and indignantly reported he would not “condescend to become the medium of even transmitting such claims”; however, he later authorized $2,961.77 to pay for the cost of the children’s care.

With the orphans in tow, Forney proceeded to John D. Lee’s home in Harmony on April 22, 1859. He had learned that Lee had some of the property of the murdered emigrants in his possession and demanded that he surrender it. On the 23rd, Lee denied he had any of the property and insisted he knew nothing about it except that the Indians took it. “Lee applied some foul and indecent epithets to the emigrants,” William Rogers reported. Lee said they slandered the Mormons “and in general terms justified the killing.”

Forney’s conduct while visiting Lee astounded his escort, who had refused “to share the hospitality of this notorious murderer—this scourge of the desert,” Lynch swore. He was outraged that Forney accepted Lee’s hospitality, despite the statements of the surviving children, who identified Lee as one of the killers. Lee agreed to accompany Forney to Cedar City and discuss the matter of the massacre with other Mormon officials, but on the way he rode ahead and disappeared. The leaders in Cedar City proved no more helpful in tracking down the stolen property. Frustrated and outraged, Forney’s party picked up three additional survivors and headed north with 16 orphans.

Meanwhile, both the U.S. Army and Federal Judge Cradlebaugh had launched their own investigations of the murders. In mid-April, Brig. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, commander of the Department of Utah, ordered one company of dragoons and two of infantry to proceed to Santa Clara to protect travelers on the road to California, investigate reported Indian depredations and provide an escort for the Army paymaster who was on his way to Camp Floyd with a large supply of “spondulicks,” as Utah’s Valley Tan reported—back pay in gold, worth a rumored half-million dollars. Johnston then ordered the “Santa Clara Expedition ” to provide protection for Judge Cradlebaugh, who was on his way to investigate the crime and, if possible, arrest the murderers.

As Forney marched north, Kanosh, chief of the Pahvants, informed him that some Indians had told him there were two more children saved from the massacre than Hamblin had collected. The information was not deemed very reliable, but after meeting the troops from Camp Floyd at Corn Creek, Cradlebaugh swore in William Rogers as a deputy U.S. marshal, and Forney sent him back south to see if he could find any other children.

Rogers soon learned that one child was at a remote settlement named Pocketville. He sent Hamblin to recover the orphan, “a bright-eyed and rosy-cheeked boy, about two years old,” who proved to be Joseph Miller, youngest son of Joseph and Matilda Miller. Rogers “inquired diligently” for the second child but learned nothing. Despite a host of legends about a surviving child who remained in southern Utah, all reliable evidence indicates that the federal officials successfullyrecovered every surviving child.

The orphans and their ages at the time of the massacre included the children of George and Manerva Baker: Mary Elizabeth, 5; Sarah Frances, 3, and William Twitty, 9 months; of Alexander and Eliza Fancher: Christopher “Kit” Carson, 5, and Triphenia D., 22 months; of Joseph and Matilda Miller: John Calvin, 6; Mary, 4, and Joseph, 1; of Jesse and Mary Dunlap: Rebecca J., 6; Louisa, 4, and Sarah Ann, 1; of Lorenzo Dow and Nancy Dunlap: Prudence Angeline, 5, and Georgia Ann, 18 months; of Peter and Saladia Huff: Nancy Saphrona, 4; of Pleasant and Armilda Tackitt: Emberson Milum, 4, and William Henry, 19 months; and of John Milum and Eloah Jones: Felix Marion, 18 months. To his credit, Forney quickly determined that “none of these children have lived among the Indians at all.” He found them “intellectual and good looking” with “not one meanlookingchild among them.”

In late June 1859, the Salt Lake probate court appointed Jacob Forney guardian of the orphans with the power “to collect and receive all property belonging to the murdered Emigrants.” Forney still hoped to recover some of the wealth looted from the Arkansans, but he and his successors failed to reclaim a single nickel stolen from the Fancher party. Forney’s craven behavior with John D. Lee disgusted James Lynch, who swore out an affidavit that called the agent a “veritable old granny.” Lynch accused Forney of assisting the coverup of the crime by undercutting the authority of federal officials like Judge Cradlebaugh by arousing “a feeling of resistance to his authority among the guilty murderers.”

Brigham Young followed the federal investigation closely. In early May, he groused that Congress had appropriated $10,000 and appointed two commissioners to return the orphans to their relatives. “What an expensive and round about method for transacting what any company for the States could easily attend to at any time, and with trifling expense,” he complained.

General Johnston, however, was taking no chances with the survivors’ safety, and he assigned two companies of the 2nd Dragoons to escort the orphans to Fort Leavenworth. As“an act of humanity,” the firm of Russell,Majors & Waddell (which would start the Pony Express in the spring) offered the children free transportation in their freight wagons, but Johnston provided more comfortable spring wagons. Forney hired five women to accompany the “unfortunate, fatherless, motherless, and pennyless children” and made sure they had at least three changes of clothes, plenty of blankets, and “every appliance” to “make them comfortable and happy.”

Forney took two of the survivors, John Calvin Miller and Emberson Milum Tackitt, to Washington, D.C., in December 1859 to provide their “very interesting account of the massacre” to the government. The next day, Brigham Young’s Washington agent reported that Forney had given the Mormon version of the massacre and would “be of service.” Young immediately responded that if Forney continued to be a “friend of Utah,” he would not lose“his reward.”

Interestingly, no record of what the two boys told federal officials survives, but even “Old Granny” had seen enough. Forney reported in September 1859 that he began his inquiries hoping to exonerate“all white men from any participation in this tragedy, and saddle the guilt exclusively on the Indians.” But it simply wasn’t so. “White men werepresent and directed the Indians,” he concluded.Forney named the “hell-deserving scoundrels whoconcocted and brought to a successful termination” the mass murder: Stake President Isaac Haight, Bishop Philip Klingensmith, Branch President John D. Lee, Bishop John Higbee and Forney’s own trusty guide, Ira Hatch. He gave their names to the attorney general, but nothing was done to bring the murderers to justice before the Civil War broke out—and nothing would be done for a dozen years.

William C. Mitchell, who was an Arkansas state senator, had picked up the other 15 children, who included his granddaughters Prudence Angeline and Georgia Ann Dunlap (but not his infant grandson, who was among the dead), at Fort Leavenworth in late August 1859, and on September 15, friends and relatives gathered at Carrollton, Ark., to welcome the orphans home. According to the Arkansian, Mitchell told the crowd the children were “kept secreted by the Mormons” until Forney offered to pay a $6,000 ransom.

No one who witnessed the return of the children ever forgot it. Mary Baker, whose husband Jack had died at the Meadows, took charge of her three grandchildren. “You would have thought we were heroes,” Sarah Frances “Sallie” Baker recalled in 1940. “They had a buggy parade for us.” Her grandmother gave each of the children a powerful hug. The children arrived home not long before Confederate guns opened fire at Fort Sumter, and Arkansas witnessed some of the most brutal conflict of the Civil War. Despite the turmoil, all the children found homes with relatives, who raised them as best they could.

According to John D. Lee, Brigham Young said that the government took the children to St. Louis and sent letters to their relatives to come for them. “But their relations wrote back that they did not want them—that they were the children of thieves, outlaws and murderers, and they would not take them, they did not wish anything to do with them, and would not have them around their houses.” However unreliable Lee’s quote might be, a generation of Mormon historians repeated the slander that most of the children wound up in a St. Louis orphanage.

Efforts continued well into the 20th century to win some kind of compensation for the survivors of Mountain Meadows, but nothing was ever done. For the 17 orphans, the pain of their loss never went away. “I remember I called all of the women I saw `Mother,’” Sallie remembered. “I guess I was still hoping to find my own mother, and every time I called a woman `Mother,’ she would break out crying.”

None of the Mountain Meadows orphans had bleaker prospects than Sarah Dunlap, who was only 1 year old when a gunshot wound almost severed her arm during the massacre. An eye disease acquired in southern Utah left her virtually sightless. After returning to Arkansas, she was educated at the school for the blind in Little Rock and settledwith her sister Rebecca in Calhoun County.

James Lynch wandered the world as a mining expert, but he never lost touch with the orphans. After retiring, Lynch visited his old charges in Arkansas, who greeted him “as a returned father.” The old frontiersman found Sarah Dunlap, now “a cultured lady of 34 years,” and he soon “wooed and won” Miss Sarah. The couple were married on December 30, 1893, when the groom was 74. Lynch ran a store in Woodberry, and Sarah taught Sunday school. They eventually moved to Hampton, where Sarah died in 1901. Her ornate gravestone and vault were “proof of the tenderness that James felt for Sarah.” For decades the community recalled how Captain Lynch “never tired of telling how he rescued her from the Mormons.”

Lynch died about 1910 and was buried next to his wife in an unmarked grave. His fellow Masons conducted his funeral, the Arkansas Gazette recalled, “the likes of which have never again been seen in these parts.” The survivors of Mountain Meadows never forgot “the brave, daring and noble Capt. James Lynch,” but he rested in the unmarked grave until March 21, 1998, when the Arkansas State Society Children of the American Revolution dedicated a monument to his memory.

Will Bagley,who operates the Prairie Dog Press in Salt Lake City, is the author of Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (see interview in “Reviews” in the December 2003 Wild West) and has a second book about the massacre, Innocent Blood, in the works. Bagley was also one of the people interviewed for a Mountain Meadows episode—coproduced by Bill Kurtis and Paul Andrew Hutton, and scheduled to air in late December 2004—of the History Channel’s Investigating History series. Also recommended for further reading: The Mountain Meadows Massacre, by Juanita Brooks.

This article was written by Will Bagley and originally published in the February 2005 issue of Wild West Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Wild West magazine today!