[dropcap]D[/dropcap]espite being widely unknown among modern Americans, Civil War buffs, and even artists, Moses Ezekiel lived a life of firsts and participated in notable historical events. He was the first Jewish cadet enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), in 1862. As corporal of the guard, he took charge of the casket of former VMI instructor and Confederate icon Stonewall Jackson as the general’s body lay in his old classroom on May 14, 1863, the night before his burial. A year later, in May 1864, Ezekiel became the only Jewish cadet, out of 256 other teenagers, to fight in the Battle of New Market. Recalling that fight after many decades, he said it “seems to always bring tears to my eyes, none of us are sorry for what we did and under the same circumstances would repeat it.” And he was the one who read from the New Testament to fellow cadet, roommate, and friend Thomas Garland Jefferson—a great-nephew of Thomas Jefferson—as the young Jefferson lay dying after the battle.

Robert E. Lee and his wife befriended Ezekiel after the war, and during a horseback ride together, the general said to Ezekiel, “I hope you will be an artist as it seems to me you are cut out for one.” Ezekiel did go on to become the only well-known American sculptor who had seen combat in the Civil War and the first renowned Jewish-American sculptor. He created numerous statues and monuments of religious, Southern, and Confederate themes throughout his life, including the Confederate monument “New South,” at Arlington National Cemetery; one of the first Confederate monuments on Northern soil, in Ohio; and the prominent statues at VMI of Stonewall Jackson and “Virginia Mourning Her Dead,” memorializing the 10 cadets who fell at New Market. The latter is still one of the most visited statues at VMI.

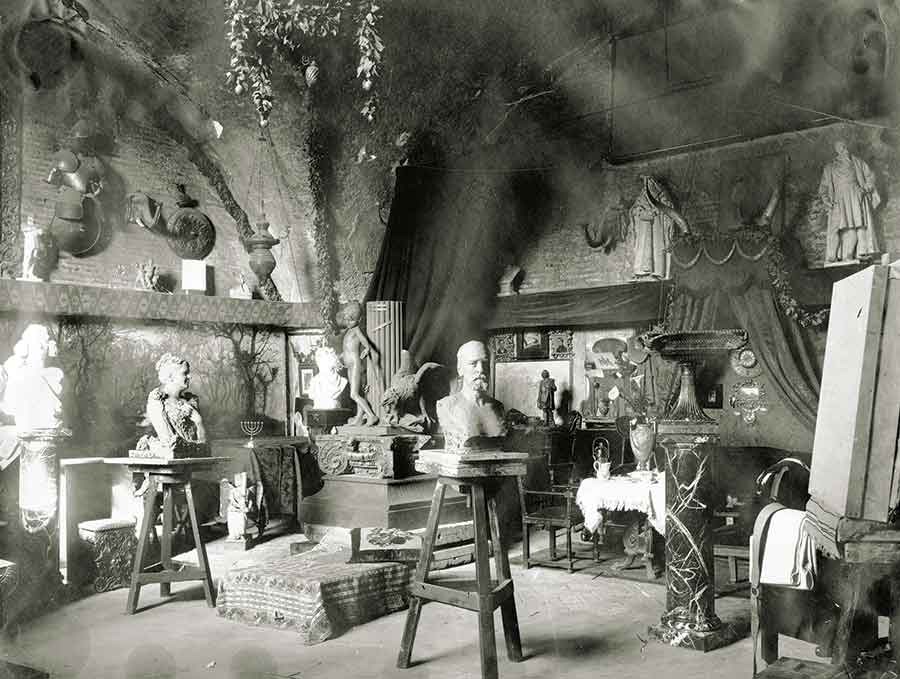

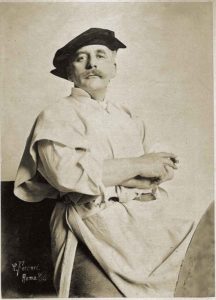

Despite these distinctions, Ezekiel’s renown faded after his death. In life, he achieved international fame and became friends with presidents, kings, and celebrities; his studio was the center of artistic and social activities in Rome, and he was knighted three times for his artwork—he received the Cavalier’s Cross of Merit for Art and Science from George, Grand Duke of Saxe-Meiningen in 1887; the Cavalier’s Golden Cross of the House of Hohenzollern from William II, Emperor of Germany in 1893; and the honorary title of Cavalier Ufficiale della corona d’Italia from King Victor Emmanuel III in 1906.

But in death, the art world ignored and forgot him because he never innovated; he emulated the classical style of the previous masters, focusing on the full human figure and historical and allegorical subjects, even when the time for that style had come and gone.

By his obscurity, he also achieved the recent distinction of being the only Virginian, Confederate, or Jewish sculptor whose work—a statue of young Thomas Jefferson outside the University of Virginia Rotunda—served as the focal point for a hostile protest against the pending removal of a Lee statue, in Charlottesville in 2017. Pro-Confederacy protesters shouted hate speech about Jews while ironically circling around the statue made by Ezekiel—a man unequivocal about his Jewish heritage and a die-hard Southerner and supporter of the Confederate cause, who had hung the Confederate battle flag in his art studio in Rome for 40 years.

In his anonymity, Ezekiel has shattered all stereotypes and assumptions. And despite his seeming invisibility, once you start looking for Ezekiel in bronze and stone, he is everywhere.

These are key moments in his life and art:

RICHMOND, Va. Born in Richmond in 1844, Ezekiel lived in the back of his grandparents’ dry-goods shop on Old Market Street, on the west side of 17th Street between Main and Franklin, near the site of what is now the Richmond Farmer’s Market. “I loved my native city as a child loves its mother,” he once wrote of Richmond.

The store “was filled with ready-made dresses of all sizes to fit any Negro woman or girl…Every Negro who was brought to Richmond from the South to be sold at auction was, on the morning of the sale, brought to our house to be dressed,” he wrote in his memoirs. Though he would come to fight for the South, Ezekiel says he didn’t believe in slavery—“In reality no one in the South would have raised an arm to fight for slavery. It was an evil that we had inherited and that we wanted to get rid of,” he said. “Our struggle…was simply a constitutional one based upon…state’s rights and especially on free trade and no tariff.”

LEXINGTON, Va. When the news broke of the bombardment of Fort Sumter and the secession of South Carolina, “bonfires were built on almost every corner of the town. Around them we little boys howled and jumped for joy,” he recalled. He says he became so enthusiastic that “I begged and entreated my grandparents to let me go to the Virginia Military Institute as a cadet”—hoping it would be a “means of my getting into the war.” He enrolled at VMI in September 1862 at age 18.

Later in life, during his art studies at the Berlin Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1869, he crafted “Virginia Mourning Her Dead,” in plaster, a female figure representing Virginia, sitting on the remains of a fortress. Thirty-one years later, in 1900, VMI asked him to create it in metal. “It was…one of the most sacred duties of my life to remodel my bronze statue…to be placed on the parade grounds of the V.M.I. [in 1903], overlooking the graves of my dead comrades so that their memory may go on in imperishable bronze, sounding their heroism and Virginia’s memory down through all ages and forever.”

NEW MARKET, Va. Ezekiel had been at VMI a little more than a year when early on the morning of May 10, 1864, the cadets were awakened by the beating of a long roll. “I think we all knew, when we heard those drums, what was coming,” he said. The Corps of Cadets was being sent down the Valley of Virginia to help General John Breckinridge “drive back the invaders…. A loud hurrah showed the willingness with which these boys between fifteen and eighteen years of age would leave their alma mater and go towards the battlefields.” They marched for four days from Lexington to New Market.

In his memoirs, he remembered back to May 15, the day of the Battle in New Market: “It was raining, and…we marched through fields of mud, in which I lost my shoes….Our battalion was beautifully in line when we crossed an open field. Halfway across this field, the Minié balls began to whistle around our ears, and the artillery shells came howling toward us.” They noticed a curve in their line and straightened out, then “we advanced in as perfect order as if on dress parade,” charging the enemy’s battery, “which had been firing its hellfire upon us,” and engaged in close-quarter fighting with pistols and bayonets before eventually hoisting the VMI flag on top of a captured Union cannon in victory.

According to VMI, “Never before, nor since, has an entire student body been called from its classrooms into pitched battle.”

CINCINNATI, Ohio In 1867, Ezekiel moved in with his parents who had relocated to Cincinnati, where he began studying sculpture, and in 1869, he left for Europe to study in Berlin. Among many sculptures that ended up in Ohio, Ezekiel created “Southern” in 1910, a soldier standing guard. Commissioned by the Robert Patton Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, it was erected at the former Union prisoner of war camp on Johnson’s Island, on Lake Erie. President Taft would tell Ezekiel he had heard that “veteran soldiers from the Northern army and the Southern army were fraternizing together there and had been photographed arm in arm with each other. ‘You have contributed a great deal towards the peaceful solution of our affairs.’”

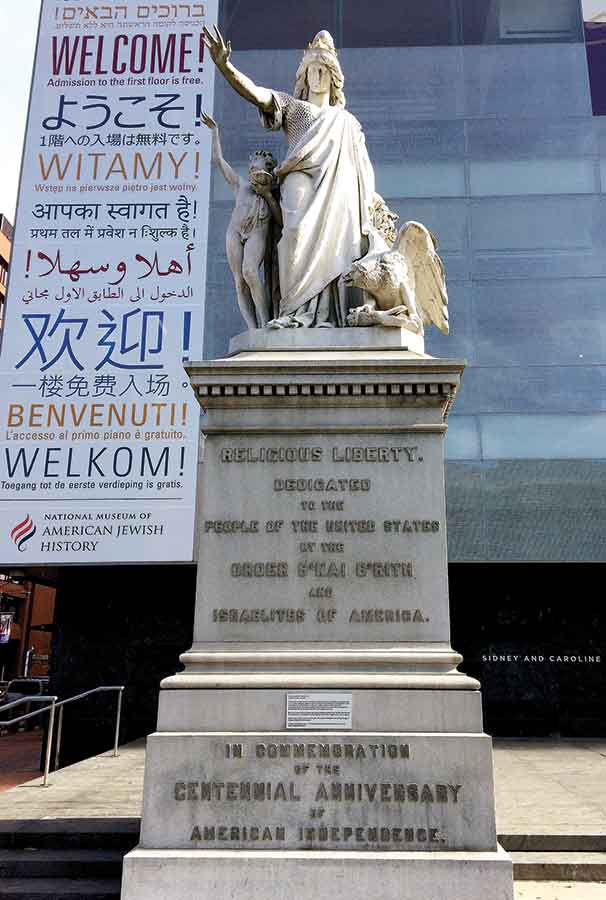

PHILADELPHIA, Pa. In 1873, Ezekiel became the first non-German and first American to win the Berlin Royal Academy of Fine Arts’ prestigious Michel Beer Prix de Rome, allowing him to study art in Rome, where he spent the rest of his life. But he deferred his award for a year because he had just received his first commission (and the first commission from an American Jewish organization to an American Jewish sculptor) from the Independent Order of B’nai Brith: a marble group sculpture called “Religious Liberty,” the first commissioned sculpture to this cause. A woman wears a 13-star crown, representing the original colonies, and clutches the U.S. Constitution, and an eagle grasping a serpent represents democracy vanquishing tyranny. It was intended for the American Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 and now sits on the grounds of the National Museum of American Jewish History within steps of the Liberty Bell.

CHARLESTON, W. Va. Ezekiel created more than 200 works of art, but a statue commissioned by the Charleston chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was perhaps the most exciting at this point in his life. It was placed in front of the state capitol in Jackson’s home town in 1910, and Ezekiel said the figure of Stonewall Jackson (a replica of which he later made for VMI) was, “in reality after 40 years the …[first] commission I ever received from the South.” Having been plagued with poverty and depression for many years, getting this commission “was a rift in the clouds that had been gathering around me.” The governor of Virginia allowed Ezekiel’s beloved VMI Corps of Cadets to come to Charleston for the unveiling.

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. The 1910 bronze Thomas Jefferson statue at UVA is a smaller replica of one originally commissioned by a Louisville businessman and placed in front of the Jefferson County, Ky., courthouse in 1901. Jefferson is 33 years old, presenting the Declaration of Independence to the First Congress, standing atop the Liberty Bell, which is draped with figures representing “Liberty, Equality, Justice, and the Brotherhood of Man.” Continuing a theme throughout his and his family’s life, Ezekiel has the figure of Equality holding a tablet that says “Religious Freedom” with the names of various deities beneath—“God, Jehovah, Brahma, Atma, Ra, Allah, Zeus.”

ARLINGTON, Va. “Religion is a term one might apply without too much exaggeration to Ezekiel’s feeling for his native Virginia. He all but worshipped the state and had an unflagging devotion to memories of the Confederacy,” according to a biographer. The year 1912 brought perhaps the most enthralling commission to Ezekiel: a request from the United Daughters of the Confederacy to make a statue in his own state, memorializing fallen Confederates: The Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery, called “New South,” intended to “permanently mark the union between North and South.”

“It is my greatest pleasure to feel that in the declining years of my life—I have had the honour to place some of my work in my own state.” In fact, he said, “I had been waiting for forty years to have my love for the South recognized.”

Although he spent his life angling for commissions and entering at least four contests to make a public sculpture of Robert E. Lee, which never came to fruition—“It was the one work I would love to do about anything else in the world,” Ezekiel said—his “New South” monument was erected in 1914 on the grounds of Lee’s former home, Arlington House, which had been seized by the Union. Surrounded by 482 Confederate graves in Jackson Circle, the bronze group statue features a heroic figure of a woman representing the South, holding a laurel wreath, with an elaborate frieze depicting various types of people going off to war, such as a blacksmith saying goodbye to his wife, and a variety of symbols commemorating the war. As reported in The Washington Post in May 1914, “It means, primarily, peace.”

President Woodrow Wilson, who presided over a ceremony to unveil the monument, said it was an “emblem of a reunited people,” and told the crowd that “this chapter in the history of the United States is now closed.”

Upon his death in Rome in 1917 and his body’s return to America after World War I, Ezekiel was buried in 1921 beneath his Confederate monument—“the work he loved the most and which he labored at with the greatest satisfaction. [He wanted to lie] among the comrades of his youth, of the heroic period of his life which he always referred to with such pride,” according to a friend. His was the first burial ceremony ever held in the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, built in 1920. His gravestone reflects the one thing of which he was most proud: “Moses J. Ezekiel, Sergeant of Company C, Battalion of Cadets of the Virginia Military Institute.”

Ezekiel’s love for the South, for Virginia, for his fellow VMI cadets, and for the Confederacy never wavered throughout his life. His focus on the past, on history: dissecting it, reliving it, studying it, glorifying it, learning from it—his life’s guiding principles—are reminiscent of the credo of many Civil War buffs and scholars: interested in times gone by, eras past, the way things were, full of melancholy or appreciation for life and times that are no longer. Like Ezekiel, those of us who spend our days looking backward feel richer for it, but we have decidedly not heeded Lee’s post-Appomattox philosophy and recommendation to Ezekiel as a young man starting out in 1866: “I have buried the past with my sword, and I never expect to refer to it again.”

Sue Eisenfeld is the author of Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal and a contributing author in The New York Times’ Disunion: A History of the Civil War. Her articles have appeared in major papers and she teaches nonfiction for the Johns Hopkins M.A. in Writing and Science Writing programs.

Moses Ezekiel Road Trip

See major works by the artist!

Chicago, Ill. In Arrigo Park: A large bronze statue of Christopher Columbus. Ohio At Johnson’s Island Confederate Cemetery: Southern. Statues at the Cincinnati Art Museum, including Eve Hearing the Voice, and the Hebrew Union College Skirball Museum Cincinnati, including Israel, his Prix de Rome winner. In the collections of the University of Cincinnati and the Cincinnati Law Library, as well as the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.

Kentucky In front of the Jefferson County Courthouse in Louisville: the original Thomas Jefferson from which the UVA statue originates, from 1901. At the Crescent Hill branch of the Louisville public library: A bust of Abraham Lincoln. At the Hickman city cemetery: The Confederate Memorial Gateway, a rare architectural piece by Ezekiel.

Ithaca, N.Y. In Sage Chapel at Cornell University: A recumbent marble statue of Mrs. Andrew Dickson White, wife of one of the university’s founders; and a recumbent marble statue of Jennie McGraw Fiske, an early benefactor to the university. In the Goldwin Smith Building, a bust of Goldwin Smith, an early history professor at Cornell. Philadelphia, PA. Outside of the National Museum of American Jewish History: Religious Liberty. At Drexel University: A bronze statue of founder Anthony J. Drexel on the plaza, and a Drexel bust in the university’s main building. In Fairmont Park: A bust of governor Andrew G. Curtain as part of the Smith Memorial Arch, a Civil War monument. Baltimore, Md. At Gordon Plaza at the University of Baltimore: Ezekiel’s last piece of work, a sculpture of Edgar Allen Poe, “our greatest poet,” claimed Ezekiel.

Washington, D.C. At the U.S. Capitol: A small marble bust of Thomas Jefferson created in 1886 by a commission from the U.S. Senate.

Charlottesville, Va. In front of the Rotunda at the University of Virginia: Thomas Jefferson. In front of Cabell Hall: Blind Homer With His Student Guide.

Lexington, Va. On the parade grounds of Virginia Military Institute, his alma mater: Virginia Mourning Her Dead from 1903 and Stonewall Jackson. In the VMI Museum: A variety of smaller statues, busts, and paintings. Lynchburg, Va. Near the intersection of Park Avenue and 9th Street: A 1915 statue of Senator John Warwick Daniel, a former Confederate staff officer and “our Southern hero and great orator,” according to Ezekiel. Norfolk, Va. At the Norfolk Botanical Gardens: 11 figures of sculptors and painters from when William Corcoran, the banker, philanthropist, and art collector commissioned a series of them for the Corcoran Gallery of Art (now the Renwick Gallery), including Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Rembrandt.