We called her Betty. The American system of nicknaming World War II Japanese aircraft gave female names to bombers, male names to fighters. Betty was actually a waitress in Pennsylvania. A member of the three-man intelligence team that picked the names thus immortalized a one-night stand.

The Japanese might have thought that amusing, but they called the Mitsubishi G4M Rikko, truncating their phrase for “land-based attack bomber.” (The G4M’s predecessor, the Mitsubishi G3M “Nell,” was also called Rikko.)

The Rikko was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s idea, abetted by the young, air-minded naval officers in his orbit. Yamamoto was a smart guy, even though he only got a C+ for his two years of English studies at Harvard from 1919 to 1921. Rather than pull all-nighters, he spent a lot of time in Cambridge playing poker. He beat his affluent opponents like borrowed mules, then used his considerable winnings to finance a summer of travel around the United States, learning as much as he could about the overconfident gunslinger he would outdraw at Pearl Harbor two decades later.

The old-timers in the Imperial Japanese Navy were battleship queens, and it was thanks to them that Japan constructed two expensive but supremely useless super-battleships, Yamato and Musashi, both sunk before their crews even knew the way to the wardroom. Yamamoto’s idea, however, was not to build more ships—you could buy a thousand airplanes for the cost of a warship, he once said—but to build a land-based bomber with huge range and great speed that could quickly fly far out to sea and fight naval battles, either defending the fleet’s capital ships or attacking the enemy.

In 1936 Japan renounced the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, which had stipulated that the capital-ship-building ratio between the U.S., Britain and Japan should be 5:5:3. The Japanese thought that was unfair, and Yamamoto’s desire to build a fleet of very-long-range torpedo bombers—no aircraft carriers needed—was in part a way to circumvent the Washington treaty: If we can’t build floating warships, let’s build flying warships.

Yamamoto’s weapon of choice was the torpedo, and the Betty was first and foremost a torpedo bomber, carrying a single 1,890-pound Type 91 tin fish—the world’s most accurate and powerful aerial torpedo right up until the end of the war. The Type 91 had been designed specifically for the Hawaii attack and Pearl Harbor’s shallow water, though there it was carried by single-engine, carrier-launched Nakajima B5N2 Kates.

The Type 91 was a remarkable torpedo that could be dropped at speeds in excess of 230 mph. It was propelled by a tiny radial engine fueled by kerosene and compressed air, and had a surprisingly sophisticated automatic roll-control mechanism. It carried a huge explosive charge, and bore large wooden tailfins that stabilized it in flight and broke away when the torpedo entered the water.

The Rikko assignment went straight to Mitsubishi, which had already paid its bomber-building dues with the G2M and G3M. The Nell was the scourge of China, ranging far and wide during the Sino-Japanese war that preceded WWII. So the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service laid down the parameters of what would become the Betty by basically saying, “Build a better Nell. Same engines, same twin-engine configuration, same size, give it some guns…just make it a lot faster and longer-legged.”

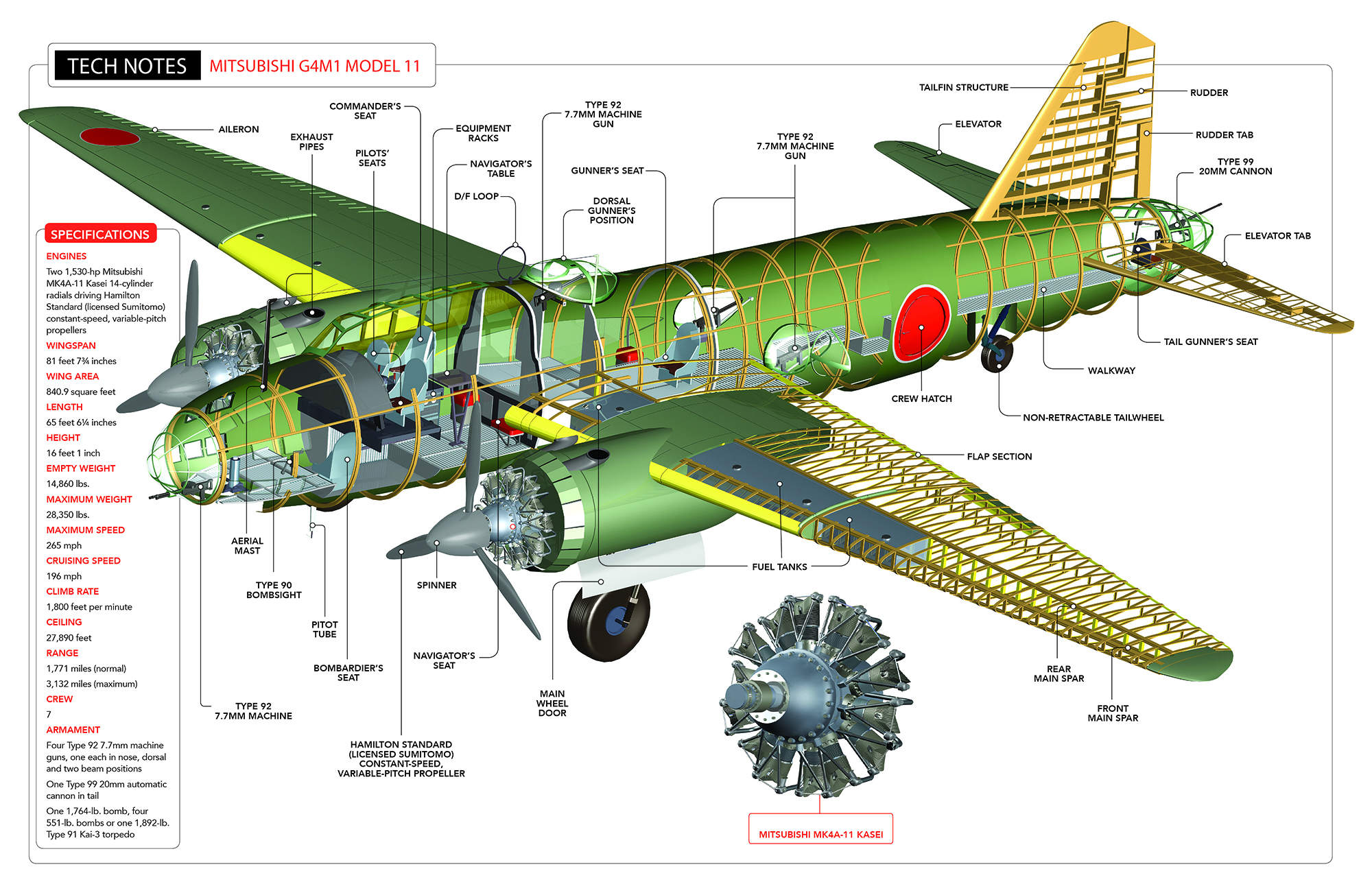

The IJNAS requirements were a top speed of 247 mph, a maximum range of almost 3,000 statute miles and a loaded range of 2,300 miles. Mitsubishi said the bomber would need four engines to accomplish that, but the IJNAS insisted on a twin-engine configuration. Fortunately for the Betty’s engineering team, Mitsu came up with a new 1,530-hp, 14-cylinder, twin-row radial with half again as much grunt as its predecessor had offered. The Betty design would work.

Some sources claim that Japan bought the original Douglas DC-4 prototype, the unsuccessful triple-tail design called the DC-4E, to serve as a model for a four-engine G4M. Imperial Japanese Airways did in fact purchase the DC-4E in late 1939 and immediately handed it over to Nakajima, which was ordered to produce a four-engine heavy bomber, the G5N, based on the Douglas design. Douglas couldn’t have played its hand better if it had tried. The DC-4E design proved to be so bad that the company started over again, producing the successful DC-4 airliner. Nakajima had no such opportunity with the G5N, which turned out to be underpowered and overly complex.

Though the Betty was initially laid out by engineer Joji Hattori, the lead designer was Kiro Honjo, a good friend of Zero fighter designer Jiro Horikoshi. Honjo had studied bomber design at the Junkers works in Germany, and was responsible for the G3M. He took over work on the Betty after returning from a fact-finding trip to the U.S. in 1938.

Before serial production of the Betty began in 1940, Mitsubishi was ordered to first create a G4M heavy fighter variant designated the G6M1. G3Ms attacked in large vee formations of 27 aircraft stacked in nine mini-vees of three aircraft each, a formation-flying nightmare. The two rearmost and outermost Nells were, no surprise, found to suffer the highest casualties from opposing fighters. So why not fill those positions with dedicated gunships? The Japanese called them “wingtip escorts,” assumedly so-named from their position in the main formation, and they were gunned up with extra 20mm cannons in place of light machine guns.

The U.S. Army Air Forces would later try the same thing with its YB-40s, which were B-17s carrying 18 or even more .50-caliber guns, flying as formation escorts. Both the YB-40 and the G6M1 were failures because they were too heavy to keep up with companion bombers that had dropped their ordnance. Mitsubishi also learned that the heavy cannons compromised the Betty’s handling.

Physically, the G4M’s salient feature was a fat but graceful fuselage quite unlike the tapering configuration of typical WWII medium bombers. Honjo gave the Betty a full complement of guns in waist, dorsal-turret, nose and tail positions, and the roomy fuselage was intended to give the airplane’s seven-man crew (later reduced to five when it became increasingly difficult to recruit aircrew) space to move around during long flights and to fill multiple positions. Honjo apparently also decided that an untapered fuselage ending in a large tail-gunner’s station made sense aerodynamically. Whether his engineering team found it aesthetically pleasing is open to question. They called the design the “snail,” sometimes translated as “slug.”

The Japanese more genially nicknamed the Betty “Hamaki” (cigar), and many sources have assumed this was a reference to the airplane’s flammability when struck by enemy fire. In fact it was another moniker based on its shape, chosen long before G4Ms began igniting frequently enough for Americans to call them Zippos.

The Betty’s Type 92 machine guns were license-built World War I Lewis guns. Drum-fed from an archaic 47-round pancake magazine atop the gun, the Lewis had a long history of aviation use. It was the first gun ever fired from an airplane, a Wright Model B Flyer, in 1912. With a relatively slow rate of fire and rifle-caliber (7.7mm) ammunition, the hand-held Type 92 wasn’t about to frighten away .50-caliber Browning-equipped Grumman F4F Wildcats, to say nothing of F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs.

The tail gun was a 20mm cannon, though a relatively ineffective one. Hand held and operating through a 20-degree arc, it required a pursuing fighter to voluntarily position itself within the cannon’s tiny field of fire, though this limitation was removed in later versions of the Betty.

But none of this mattered, because the Betty had a fatal flaw, and Kiro Honjo knew it.

In order to achieve the G4M’s great range and performance, he was forced to equip it with the largest possible fuel tanks and to forego rubberized self-sealing protection for them. Nor did he provide armor for the crew. (His friend Horikoshi seems to have taken the technique to heart in designing the Zero.) The Betty’s wet wings were its tanks, with fuel cells neatly defined by the main spar and a secondary spar forward of it, the ends sealed by solid wing ribs. There was no self-sealing mechanism, which would have required a 1¼-inch-thick soft rubber layer weighing about 660 pounds, either inside or outside the fuel tanks, substantially reducing the tanks’ capacity.

After 663 Bettys had been manufactured (some 2,400 would ultimately be built), Mitsubishi began to fireproof the wings by applying a thick self-sealing layer on the outside of the lower wing skins. This maintained the internal fuel capacity but adversely affected the airplane’s aerodynamics. The rubber mat shaved about 6 mph from the G4M’s speed and reduced range by almost 200 miles. Had they tried putting a matching mat on the exterior top of the wing tanks as well, the airplane probably would never have gotten off the ground.

The final version of the Betty, the G4M4, had an entirely new laminar-flow wing with integrally self-sealing fuel tanks. The benefits of laminar flow were probably illusory on Bettys, since IJNAS aircraft of all types had paint jobs that ranged from beater-bad to junkyard special, peeling and flaking in a manner that would have tripped any incipient laminar airflow. For years it was assumed that the Japanese simply didn’t know how to make good paint, but the reason was even more basic. Mitsubishi aircraft were delivered to combat units in natural metal and spray-painted with camouflage in the field…without the benefit of primer.

The Betty was the product of excellent engineering pushed to the limit and then slightly beyond, to meet requirements created not by aviators but by military bureaucrats. Those procurement officers were aware of the airplane’s main flaw but chose to accept it, dooming many crews.

None of this mattered during the Sino-Japanese campaign, when Bettys were escorted by the new, long-range A6M2 Zero. Nor was it a factor during the early days of WWII, when Bettys ranged virtually unopposed against the Philippines, Australia and, in their greatest single victory, against the Royal Navy.

The British had assembled a Singapore-based task force around the battlecruiser Repulse and the battleship Prince of Wales, with which they intended to protect their Southeast Asian territories. Airpower proponent Billy Mitchell might have told them this was a dumb idea, having demonstrated in the early 1920s what bombers could do to capital ships. The day of big-gun ships was over, though the world’s navies didn’t yet know it.

Nobody is sure how many torpedoes hit the two British battlewagons, but three days after Pearl Harbor, wave after wave of Nells and Bettys achieved at least nine Type 91 hits and possibly as many as 21. It was the first time that aircraft alone had sunk fully maneuverable capital ships at sea. In one stroke, it totally removed the Royal Navy from any effective role in the Pacific War.

For the Betty, however, it was all downhill from there. The next time the Mitsubishi bombers attacked Allied ships, on February 20, 1942, they were after the U.S. carrier Lexington and its task force. Fifteen of the 17 unescorted Bettys were shot down.

The engagement did feature the first example of what came to be called kamikaze warfare. One Betty on a bomb run against Lexington had an engine shot entirely off its mounts, by Lieutenant Butch O’Hare of ORD fame, and then did its best to crash into the carrier. It missed, but it has been written that the entire corps of Rikko pilots, aware that they were riding fiery mounts, had agreed to seek out a target to crash into if their airplane was terminally damaged. One highly regarded Japanese book about Bettys in combat is titled Wings of Flame. (Perhaps something is lost—or gained—in translation.) Betty crews carried no parachutes, since bailing out wasn’t an option.

In August 1942, during the Guadalcanal campaign and this time escorted by fighters, 18 out of 23 attacking Bettys were shot down—the single worst G4M loss during the entire campaign. More than 100 Bettys were lost over Guadalcanal. The G4M air wings eventually learned that daytime missions against well-defended U.S. ships would result in unacceptable losses. The Mitsubishis were large, ponderous targets and needed to follow stable courses during torpedo runs. Anti-aircraft guns decimated them.

The Japanese had become outstanding night pilots during the Sino-Japanese war, when they flew 500-mile missions in darkness purely by dead reckoning, sometimes serving as navigation lead ships for their own fighter escorts. Now they revived the technique with night torpedo missions against U.S. ships that were essentially blind. It worked for a while, but increasingly inexperienced G4M crews and the chaos of night attacks rendered even these desperate measures ineffective.

Amid it all came one of the Betty’s most notorious flights: the mission to carry Admiral Yamamoto on an inspection tour of the Solomon Islands in April 1943. The admiral’s own noted punctuality doomed him, for the two G4Ms carrying him and his aides intersected perfectly with 16 P-38 Lightnings sent on a precise mission to intercept him over Bougainville, and Yamamoto died in the very airplane that he had helped create.

One of the Betty’s last combat assignments was to carry torpedo-shaped Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka single-seat kamikaze rocket planes to within striking distance of U.S. fleets. Striking distance meant 20 miles or less, thanks to the Ohka’s tiny load of rocket fuel, and Betty pilots too often pulled the release handle early. Some ships never knew they had been attacked, since the Ohkas glided into the Pacific before even coming within sight.

The rocket planes were heavy—more than 4,700 pounds—so the overloaded Bettys carrying them were particularly vulnerable to fighter interception. The first Betty/Ohka strike, toward U.S. aircraft carriers off Kyushu in March 1945, consisted of 18 Bettys escorted by 30 Zeros. Within 20 minutes, Hellcats had shot down all 18 bombers. Only one U.S. ship, the destroyer Mannert L. Abele, was ever sunk by an Ohka, and it cost six out of the eight attacking Bettys.

The Betty’s swan song would have involved a fleet of some 60 troop-carrying G4Ms (their roomy fuselages made them particularly appropriate for this) that were to simultaneously land on Guam, Saipan and Tinian. They would disgorge hundreds of commandos dressed in USAAF uniforms. In the confusion, the Japanese troops were to destroy as many B-29s as possible and then head into the jungles to continue fighting as guerrillas. One specially detailed Betty crew was even assigned to seize a Superfortress and fly it back to Japan. The atomic bombs put an end to this sideshow.

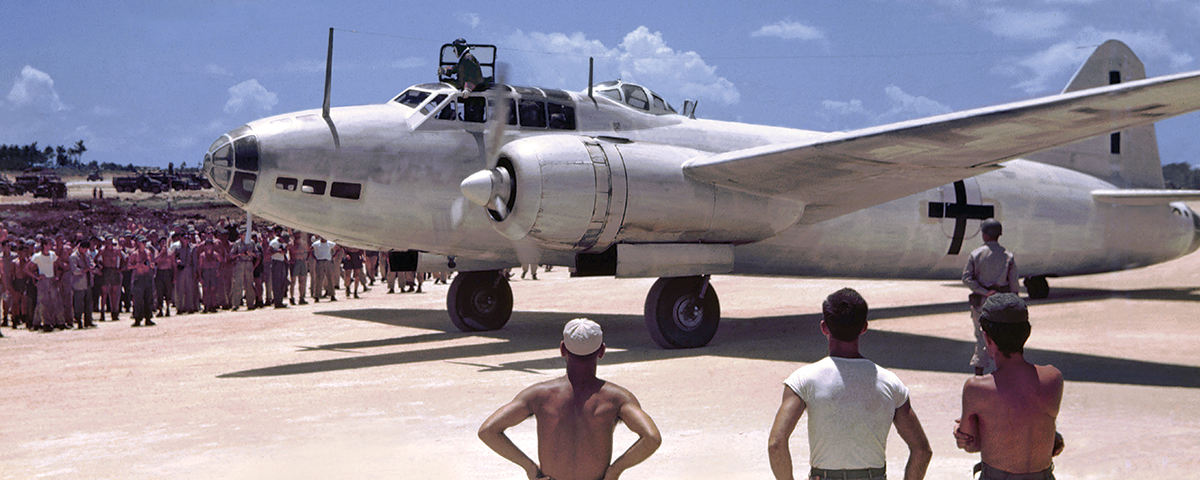

Bettys flew on the opening day of WWII, and they helped close out the war as well. A G4M1 and a G6M1-L, whitewashed and given green-cross insignia, carried a group of Japanese officers assigned the job of arranging the details of surrender negotiations. The August 19, 1945, mission is often characterized as having “carried Japan’s surrender delegation,” but the officers aboard had no such function; the surrender was actually ratified on September 2.

The “white Bettys” flew from Japan to Ie Shima, a small Okinawan island, where the Japanese were transferred to a C-54 and carried on to Manila to meet with Douglas MacArthur and his staff. Homeward bound, the Bettys were appropriately snakebit. One ran off the runway during takeoff from Ie Shima and damaged its landing gear; the other ran out of fuel and ditched short of its destination in Japan.

Not a single Betty survives as anything more than a battered, partial hulk—a situation unique among warbirds built in such numbers and active in so much combat. After the war, the USAAF was test-flying at least one Betty that had been captured in the Philippines, one of four or five flyable G4Ms that the U.S. liberated. Their fate is unknown, though the cockpit and nose of one, plus the tailcone, ended up in storage at the National Air and Space Museum.

The only Betty remnant in Japan is owned by a wealthy automotive importer/exporter, Nobuo Harada. It currently consists of a fully restored fuselage, much of it fabricated by Harada’s restorers, in a museum near Tokyo. Another hulk is in the collection of Australia’s Darwin Aviation Museum.

One of the best-known Betty carcasses was on display for years at the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, Calif. It was recovered from New Guinea in 1991 by warbird salvager Bruce Fenstermaker, in a joint venture with the Santa Monica Museum of Flying. The deal with Santa Monica somehow got derailed and the hulk was instead acquired by Ed Mahoney, who put in on display in Chino—a wrecked fuselage, inboard wings, engines and nacelle—as a jungle diorama.

In November 2015, billionaire Paul Allen bought the wreck for his Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum in Seattle. Judging by what Allen has done with other such acquisitions, it is possible that this Betty will someday fly again. Almost certainly it will eventually be fully restored and placed on display.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: Mitsubishi G4M Betty, by Martin Ferkl, and Mitsubishi Type 1 Rikko ‘Betty’ Units of World War 2, by Osamu Tagaya.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!