When the U.S. Air Force played Misty in Vietnam, the enemy ran for cover.

As U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War escalated in the mid- 1960s, the angry skies over Southeast Asia took a mounting toll on American aircraft. Propeller-driven “slow movers” like the Cessna O-1 Bird Dog and O-2 Skymaster, used primarily by forward air controllers (FACs), were particularly vulnerable to enemy anti-aircraft fire, and before long the losses became unsustainable. As a result, in June 1967 Seventh Air Force commander General William “Spike” Momyer initiated a top-secret program called Commando Sabre that was designed to test whether the superior speed and maneuverability of jet aircraft would improve survivability in areas where stiffening enemy air defenses made it too dangerous for slow movers. The Air Force formed a small volunteer unit of combat-seasoned aviators, nicknamed “Mistys,” and gave them the task of developing groundbreaking Fast FAC tactics.

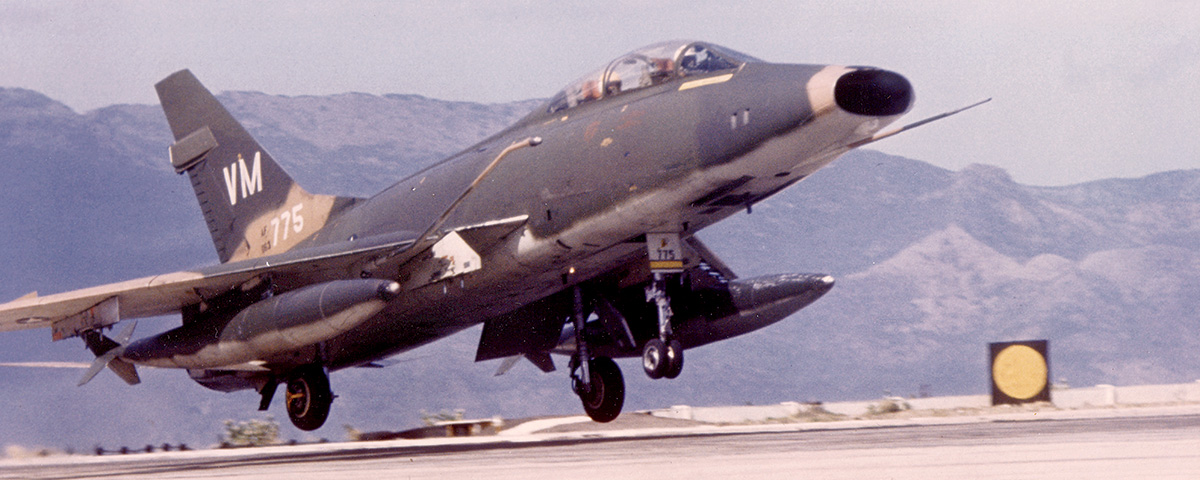

Mistys flew the North American F-100F, a two-seat version of the mighty Super Sabre (affectionately known as the “Hun”) armed with two rocket canisters and a pair of 20mm cannons. The Air Force, in true bureaucratic fashion, chose the F-100 over the more advanced McDonnell RF-4 Phantom mainly because it was less expensive. “I guess we were cheap and expendable,” joked Major Bill Douglass, the Mistys’ first director of operations.

Mistys stared death in the face on every sortie and suffered one of the highest loss rates of the war. “Everyone thought we were nuts!” recalled Misty pilot Jack Doub. Likewise, Jim Mack, the 24th pilot to volunteer for the unit, observed, “War is hell, and especially for the Mistys, as we often thought we were taking boxing gloves to a knife fight.”

Despite the dangerous and costly nature of the operation, Commando Sabre would blossom into arguably the most successful air mission of the war. Indeed, F-100 Fast FACs gave Charlie more than a few unpleasant surprises in their day. Two missions in particular—the “Great Truck Massacre” of March 20, 1968, and another that annihilated nearly 1,000 enemy troops caught in the open on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in February 1970—were remarkable feats in the annals of air warfare. Their results would not be surpassed until two decades later, when more sophisticated American fighters found Saddam Hussein’s army retreating on the roads from Kuwait City.

The Commando Sabre experiment began with 16 pilots and four aircraft as Detachment 1, 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron, at Phu Cat Air Base in South Vietnam on June 15, 1967. The unit’s first commander, Major George “Bud” Day, loved Johnny Mathis’ rendition of the song “Misty,” so pilots adopted it as their radio call sign. Although chosen on a whim, the Misty nickname stuck. From then on, everyone except higher headquarters referred to the unit as Misty rather than by the program’s official name.

One of the song’s verses is especially appropriate for a squadron tasked with marking targets for other fighters: “Don’t you notice how hopelessly I’m lost, that’s why I’m following you.” Misty pilots became intimately familiar with the nooks and crannies of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and were adept at guiding other fighters to well-concealed targets under the jungle canopy. Fighter-bombers often showed up on the scene with inadequate SA (situational awareness) and low gas, but with the Mistys’ help they could “make a fast pass and haul ass.”

The Fast FAC program was actually the brainchild of Jim Chestnut, an experienced fighter pilot and staff officer assigned to the Seventh Air Force. Chestnut would go into the field, solicit opinions on how to improve operations and relay promising ideas to General Momyer. After reviewing “every BDA [battle damage assessment] report on every mission,” Chestnut was particularly dismayed by the poor results reported for strikes in Route Pack 1 (RP-1, the area immediately north of the DMZ) and southern Laos. He convinced Maj. Gen. Gordon “Gordy” Blood, the Seventh Air Force deputy commander for operations, that they could get more bang for the buck if high-speed jets armed with “Willie Pete” (white phosphorus) smoke rockets marked targets for fighter-bombers.

At the time, the standard practice for pilots who were unable to drop their bombs due to weather or other factors was to jettison the ordnance while returning to base. The beauty of Chestnut’s plan was that these fighters could instead contact the Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center (ABCCC) and be redirected south to bomb lucrative targets marked by Fast FACS. Unlike in-country missions that required notifying the local province chief 24 hours in advance of a strike (which usually meant a target was no longer there), Chestnut thought these real-time sorties would have a good chance of catching the enemy “moving in the open with their pants down.” He also predicted that survivability “should be good” if pilots maintained discipline and stuck to well-defined tactics.

Chestnut’s prediction that the program would prove effective was solidly on the mark, but his risk assessment was dead wrong. Of the 157 Mistys who flew in the unit between June 1967 and May 1970, 34 were shot down (22 percent) and two were shot down twice. Although never statistically proven, it was a widely held belief among aircrews that fighter pilots working with Misty suffered the second highest loss rate in the war, behind only the Mistys themselves.

In an ominous forewarning of the dangers of the operation, the first Misty commander was also the first to be knocked out of the sky. On August 26, 1967, Major Day was flying in the back seat of No. 56-3954 on his 23rd Misty mission. He and Captain Corwin “Kipp” Kippenhan were performing visual reconnaissance in RP-1 in search of a reported surface-to-air missile (SAM) site when, according to the after-action report, their jet was “hit by accurate, intense, barrage 37mm flak….the crew ejected due to loss of flight controls and illumination of the engine fire light.” Kippenhan was rescued, but Day would become a POW and endure more than five years of torture. Despite debilitating injuries, he continued to offer maximum resistance and was later awarded the Medal of Honor for “bravery in the face of deadly enemy pressure.”

Commenting on his relatively short Misty tour, Day said: “We had to learn to operate and survive in a very dense threat environment while operating for extended periods at low altitude—dicey stuff! Our loss rate during the first six months was 42 percent—a steep, expensive and tragic learning curve.”

Captain Wells Jackson vividly recalled his own harrowing introduction to Misty: “I watched those tracers come up and streak past the fuselage and canopy. The 37mm rounds looked like flaming golf balls and 57 millimeters looked like flaming baseballs. A shock wave comes off the nose of each round as it goes through the air, and when a round comes very close to the fuselage, the shock wave pushes against the metal skin of the airplane, causing it to pop in and out. This ‘oil canning’ sounded just like someone was taking a hammer and striking the side of the airplane.

“During my first rides this was very disconcerting; however, the pilots I flew with were experienced and seemed to be oblivious to the fact that there were large chunks of red hot steel surrounding high explosive charges traveling at very high velocities just outside my plastic canopy, sent our way on purpose by an enemy force that was trying to kill us! Instead of reacting to the obvious danger, they calmly pointed out the different characteristics to me, so I could identify the different rounds by myself in the future.”

Seventy-six percent of all Fast FAC losses during the Vietnam War were from AAA hits incurred while flying below an altitude of 4,500 feet. Most losses were from 37mm or larger guns. Headquarters would later try to prohibit flight below 4,500 feet, but that rule was largely ignored because pilots could not effectively do their job at nosebleed altitudes. Moreover, the Mistys thought Seventh Air Force reasoning was faulty because it would expose them to an even greater number of AAA batteries when they were flying through concentrated flak traps. “I don’t remember ever flying that high,” commented Jack Doub. “If you ever popped up in altitude, North Vietnamese gunners would just kill your ass.”

Because the mission required Misty pilots to fly at low altitudes for long durations, they developed specific tactics to help counter the constant triple-A threat. They executed the “Misty Weave,” a maneuver that involved a series of 4 to 6G turns in which they would slide from side to side to complicate enemy gunners’ targeting solutions. Mistys also tried to maintain at least 450 knots of airspeed. Speed was life. If the airspeed dipped below 400 knots during hard maneuvering, the guy in back would usually tell the pilot in less than friendly language to move it.

Speed and luck helped Don Shepperd and Jim Fiorelli survive a close encounter with a Russian-made infrared (IR) shoulder-fired missile. Flying at 1,500 feet, the pair had just lost sight of a speeding truck that disappeared under the jungle canopy when “a flaming lance-like object flew from right to left about 1,000 feet in front of our airplane.” They were a little perturbed because intelligence had not told them to expect the threat. After landing, Shepperd and Fiorelli interrogated their intel officer and learned he knew all along that the Russians were starting to supply the North Vietnamese Army with IR SAMs for a big push south. When Fiorelli asked why he had not informed them before the mission, he said, “They are low altitude missiles, and we just assumed you guys obeyed the rules and flew at 4,500 feet and wouldn’t be affected.” An ugly altercation was narrowly averted.

As an experienced, combat-proven Misty, Don Shepperd helped instruct and evaluate new pilots. While watching over Lanny Lancaster on his first front-seat Misty sortie, he would kick off a chain of events that led to the Mistys’ most successful mission of the war, the Great Truck Massacre of March 1968.

Shepperd directed Lancaster to fly through RP-1, north along Routes 101 and 151, but that proved unproductive due to heavy cloud cover. Noting that the weather in adjacent Route Pack (RP-2) was clearing, Lancaster suggested that they take a look even though RP-2 was the Navy’s responsibility.

Top Air Force generals and Navy admirals, not wanting to cede control of air assets to a single planning authority, had developed an air control plan that divided the country into six Route Packages. The Air Force was assigned primary responsibility for Route Packs 1 and 5, while the Navy was assigned 2, 3, 4 and 6. Route Pack 6 was later divided into 6A and 6B, with the Air Force assigned 6A and the Navy 6B. Each service had its own geographic responsibilities and essentially ran uncoordinated air wars in its own fiefdoms. (This failure of the services to work together was a driving factor behind doctrinal changes that now require the appointment of a joint forces air component commander, a single officer responsible for crafting a unified air campaign effort.)

Shepperd agreed, and they flew north. Two minutes later Lancaster saw two, then three trucks. More and more trucks soon came into view. Lancaster climbed for altitude and called “Cricket,” the ABCCC, to share the welcome news of his find. The weather continued to improve, revealing a huge enemy convoy. Lancaster stopped counting at 50, but he estimated there were 150-200 vehicles, including 75 trucks backed up bumper-to-bumper in a large group. Shepperd snapped a recce photo that would later reveal 24 trucks in a single frame. The Mistys rejoiced in finding such ripe targets.

The trucks were rolling south, so Lancaster pushed the stick forward, dived their F-100 to just above tree level and buzzed the convoy in hopes of making it stop. Instead of halting and abandoning their vehicles, though, the enemy drivers accelerated. The two Misty pilots could not wait for other fighters to arrive, so Lancaster strafed the lead truck with his 20mm cannons. At that point, many of the drivers panicked, abandoned their trucks and headed for trenches along the roadside. Lancaster and Shepperd continued to make low, threatening passes and lob an occasional rocket to keep the truck convoy lined up on the road as they waited for the bomb-laden fighters.

Two F-4 Phantoms armed with AGM-12 Bullpup guided missiles arrived first. The F-4 flight leader quickly rolled in on the convoy, but his first missile promptly nose-dived into the ground. “Here we go again,” groaned Shepperd and Lancaster. The F-4 launched a second missile, but once again it failed to guide. Shepperd grimaced at the prospect of another blown opportunity.

After a few notably poor experiences working with Phantom crews, Misty pilots generally preferred working with Republic F-105s rather than F-4s. For example, a couple of weeks earlier one Misty crew had unsuccessfully tried to vector in a two-ship flight of F-4s to finish off a small convoy of trucks. F-105s had crippled many of the vehicles, but they had to leave before finishing the job because they ran out of ammunition. The F-4 flight leader radioed that he had the burning trucks in sight, yet he and his wingman proceeded to fly east and pickle their bombs in the Gulf of Tonkin. The Misty pilot was dumbfounded. He radioed: “Fox Lead, Misty. You dropped all your stuff in the water!” The F-4 pilot responded: “Roger, Misty. It’s a counter.” After pilots flew 100 missions over North Vietnam (no matter how successful or, in this case, unsuccessful), they were allowed to rotate back to the U.S.

Another example involved a Phantom jockey out of Cam Ranh Bay. After losing sight of the target, despite the fact that it was clearly marked with Willie Pete and was smoking from successful attacks by three of his formation members, the errant pilot initiated a bombing run in which he missed not only the target, but the entire valley where the target was located. Instead, he plunked his Mk. 82s in close proximity to the Mistys, who were orbiting several miles away.

The F-105 aircrews, on the other hand, seemed to have perfected a swirling aerial dance to deliver their ordnance with precision. The proven workhorse of the Vietnam War, the F-105 Thunderchief, or “Thud,” accounted for 75 percent of America’s bombing strikes. In fairness to the F-4 crews, their aircraft was relatively new and pilots were just mastering its intricacies. Phantom pilots spent a lot of their time on other important missions, such as MiG sweeps. Moreover, the vast majority of F-4 crews were solid bombers, but a few bad apples managed to taint their reputation among the Mistys.

Fortunately for Shepperd and Lancaster, the F-4 crews they were working with on March 20 managed to overcome technical difficulties and deliver the goods. The second F-4’s missile attack found its mark, and the Phantom pilot yelled “Bull’s-eye!” on the radio as his missile smashed into the tail end of the convoy. Three trucks were instantly vaporized, and a section of the road disappeared, bottling up the convoy.

As the F-4s departed, a flight of four Navy A-7 Corsair IIs checked in. They came down on Shepperd and Lancaster’s wing to fly a low, slow pass above the convoy and observe their targets. The A-7s then dropped cluster bombs all over the traffic jam, destroying so many trucks that it was hard to get an accurate count; the Mistys counted at least 79 trucks damaged or destroyed, but the BDA was incomplete because Lancaster and Shepperd were low on fuel and had to depart shortly thereafter. The KC-135 tanker that was supposed to provide them with gas had gone home early, so the Mistys diverted to Ubon, Thailand.

The next day, other Mistys went back to the same area and directed strikes against enemy cleanup crews sent to reopen the trail. Celebrating this great victory, the Mistys’ classified mission report proudly stated, “This is the highest number of trucks ever seen or destroyed under the direction of the Misty Super-FACs and it is doubted if such a lucrative target will again present itself.”

As luck would have it, the Mistys did wreak mass havoc on the enemy once again, but this time troops, not trucks, were on the receiving end. In February 1970, Major Jack Doub and Captain Mike Hinkle were making a final, late-afternoon swing through an area in southern Laos that was criss crossed with infiltration routes. Doub’s favorite hunting ground was a section of the Ho Chi Minh Trail that wound around the side of some fairly steep mountains. He thought bombing that segment of the trail would give the enemy the most trouble, so any time he was making the last Misty flight of the day, he gave priority to that area.

Doub particularly liked the handiwork of Thuds loaded with Mk. 117s, and would direct them to drop their bombs on or just above a road. This caused massive landslides, completely obliterating the road and making it at least temporarily unusable. To his great annoyance, he would return the next day to find the road not only open but showing evidence of heavy use during the previous night. “How can those guys get that road open without heavy equipment?” he wondered.

Mistys rarely found bulldozers and other earth-moving equipment because the North Vietnamese Army did not have them in great numbers. Instead, the NVA relied on troops with shovels to clear off landslides and refill bomb craters. They were adept at opening roads along the trail despite persistent American bombing.

Doub and Hinkle’s interest was piqued when they saw a cloud of red dust rising from the jungle. They snaked down through valleys and popped up to take a look from a few miles away. To his astonishment, Doub saw “dozens of lines of NVAs, each about ten yards below the one above—hundreds and hundreds of troops busily shoveling spade-fulls of dirt to their comrades in the next line beneath them, who, in turn, passed it down to the next line etc., etc. There were literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of troops hustling that red dirt down the mountain, so that the night’s motorcade could commence at darkness, when the Mistys departed! I was absolutely stunned, and, I must admit, just a bit impressed by the resolve shown by our enemy. It was the largest human excavation project I’d ever seen!”

Doub and Hinkle contacted the ABCCC, and the controller vectored one of the last flights of fighters available that day toward the Mistys. The incredulous controller kept repeating, “Misty, say again how many troops you’ve got surrounded down there?”

Retelling the story a number of years later at a Super Sabre reunion, Doub actually gave credit to F-4s for what happened next. But Bill Hosmer, a fellow Hun pilot (not a Misty), corrected him, jokingly shouting, “You know damn good and well that no F-4 driver ever dropped bombs that good!” It turns out that Hosmer himself, an old Thunderbird leader, and his wingman were responsible for the carnage that would follow.

Doub liked to fly with LAU-59 rocket pods loaded with a combination of Willie Pete and high-explosive incendiaries. An experienced Misty, he had mastered the art of firing rockets. During his three tours in Vietnam, Doub amassed an amazing 572 in-country missions. The Air Force Association would later honor him for completing the most fighter missions of any American in Southeast Asia. He could bend the jet around the side of a mountain and fire his rocket pod from behind a tree and still smack the target.

Doub was worried that if he marked the target, most of the troops would scurry to safety before the fighter-bombers arrived. But not marking the target would be risky. “You tell a jock to ‘Hit my smoke,’ and he’ll do it most of the time,” remarked one Misty. “If the smoke isn’t there, and he has to acquire the target on his own, he will most probably miss; maybe not by much, but far enough that optimum results are not achieved.”

Doub became confident enough to take a chance after he heard the businesslike Hosmer check in on the radio. Hosmer quickly located the target and pickled his entire rack in the center of the dust cloud. Bingo! Doub couldn’t contain his excitement, gleefully yelling, “2, put your bombs in the middle of No. 1’s smoke!” Hosmer’s wingman duplicated his flight leader’s success. After the explosions subsided, Doub saw that a huge chunk of the mountain was gone. Not only had the landslide area been hit, the entire mountaintop was about 100 feet lower.

Doub and Hinkle figured the two Huns under their direction had killed about 1,000 NVA soldiers, but they settled on a conservative 300-400 to relay to the ABCCC. They lowballed their claim because they didn’t think the staff in Saigon would accept such a high count. Sure enough, Hosmer was extensively grilled by his wing commander the next morning. “But, being the guy he is, old T-Bird 01 stuck by his guns,” said Doub. “It’s a great tale; we caught ’em by total surprise.” Doub and Hinkle’s discovery had led to perhaps the largest single-mission body count of the war.

It took a different breed of aviator to volunteer for Misty duty. Most were young lieutenants and captains who were eager, enthusiastic and uninhibited. While some didn’t survive their dangerous mission, many went on to successful careers in the military, business and industry.

There is no question that the Misty program had an impact on the war effort in Vietnam far out of proportion to its size. A little more than a year after the start of Commando Sabre, the Air Force created other Fast FAC units in hopes of multiplying the Mistys’ success. Using the call signs Stormy, Wolf, Loredo, Tiger and Owl, F-4 Phantom units picked up the Fast FAC role and built on the Mistys’ proud heritage.

USAF Lt. Col. Lawrence Spinetta is the commander of the 11th Reconnaissance Squadron and a member of the Air Force Historical Foundation’s board of directors. For additional reading, he recommends: Misty: First Person Stories of the F-100 Misty Fast FACs in the Vietnam War, by Don Shepperd; and Bury Us Upside Down: The Misty Pilots and the Secret Battle for the Ho Chi Minh Trail, by Rick Newman and Don Shepperd.

Originally published in the July 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.