Józef Piłsudski saved Poland by handing the Red Army one of its greatest defeats ever.

IN EARLY 1920, IN THE WAKE OF WORLD WAR I, Europe was desolate and bankrupt. President Woodrow Wilson’s attempt to insert the United States into international affairs as a leader and defender of democracy had ended in disaster for him and his party. Unable to persuade a Republican-controlled Congress to sign the Versailles peace treaty, he had been felled by a stroke that left him semiparalyzed and bewildered. His country was in much the same condition. Later in the year, American voters would put Republican Warren G. Harding, who had promised a “return to normalcy,” in the White House.

While humdrum prevailed in America, in Eastern Europe and Russia a drama was unfolding that made leaders on both sides of the recent war increasingly anxious. In 1917, with Tsar Nicholas II overthrown in a revolution, liberals and conservatives had struggled for control of Russia. Out of the chaos came a new movement, Soviet Communism, led by an electrifying visionary, Vladimir Ilich Lenin. Western nations, notably Britain and France, were so terrified that they shipped conservative Russians millions of dollars’ worth of guns and supplies. A year of savage civil war ensued, with the Communists emerging as the victors.

The experience convinced Lenin and his chief adviser, Leon Trotsky, that Russia would never be safe with such enemies arrayed against it. Their answer: export the revolution, turn Western Europe into Communist states, and make Russia’s cause a movement that would transform the world. Where better to launch this transformation, Lenin and Trotsky reasoned, than Germany, filled as it was with disillusioned ex-soldiers and unemployed civilians. The sight of a Communist army preaching the rebirth of hope and pride, as they saw it, would galvanize Germans—and intimidate the rest of war-weary Western Europe.

ONLY ONE NATION STOOD BETWEEN RUSSIA’S BORDERS AND GERMANY: Poland. By most standards, though, this was closer to a joke than a problem. Poland had not even existed as a nation for 123 years. Since 1795 it had been divided among Germany, Austria, and Russia. Subsequent shifts of territory in the 19th century had left Russia in control of most of the land that had been Poland. But instead of forcing the Polish people to submit in humiliation, the dismemberment of their country turned them into passionate patriots. During World War I they had joined the Russian, Austrian, and German armies and had fought as volunteers in the French army.

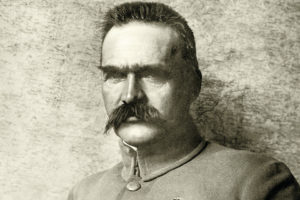

Lenin and his cronies thought they could persuade the leaderless Poles to become Communists—or kill them if they proved intransigent. But the Poles had a secret weapon: Józef Piłsudski. A burly 51-year-old general, Piłsudski had spent most of his life fighting for Poland’s restoration, sometimes as an urban guerrilla, sometimes as an agitator who published underground newspapers and occasionally robbed banks to keep his cause alive. He became a general during World War I, leading some 20,000 Poles who fought as a separate legion in the Austrian army.

In 1916 the increasingly desperate Germans, confronted by Russia’s seemingly inexhaustible manpower, persuaded the Austrians to transfer the Polish legion to their army. But Piłsudski, who came with them, refused to take the oath of allegiance required of every German soldier. The infuriated Germans threw him into the fortress of Magdeburg and dissolved the legion. All but a handful of the Poles vanished, and Berlin’s hopes of a Polische Wehrmacht went with them. Two years later, with two million Americans in the war on the Western Front, Germany’s dreams of victory collapsed and Kaiser Wilhelm II began contemplating life as an exile in Holland.

Piłsudski was freed from the Magdeburg prison and headed for Warsaw. He arrived on November 11, 1918, the day Germany signed an armistice with the Allied powers. As people danced in the streets from Paris to San Francisco, Piłsudski proclaimed the rebirth of the Polish Republic and called on his followers in the Polish Legion to join him. They briskly disarmed Warsaw’s dismayed German garrison and took control of their erstwhile capital city.

But the Polish Legion, numbering barely 20,000 men, was merely a pest in the path of the 200,000-man “Army of the West” that the Communists were readying to unleash. Trotsky and Lenin had picked their best generals—almost all of them former tsarist officers—for the new army. Leading them was 27-year-old Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky, a handsome aristocrat with little interest in anything but military glory. Command of the Army of the West further fueled his already blazing ambition. Lenin made no attempt to conceal the long-range goal. “By attacking Poland we are attacking the Allies,” he declared. “By destroying the Polish army we are destroying the Versailles peace, upon which rests the whole present system of international relations.”

Lenin and Trotsky decided there was no point in wasting time. They ordered Tukhachevsky to invade Poland, even though little more than half his projected army had been assembled. On the vast plains of Eastern Europe, where the ability to move and maneuver was essential in waging war, Tukhachevsky’s forces collided with an extraordinary number of aggressive, angry Poles. Throughout 1919 Piłsudski had worked tirelessly to assemble an army fierce enough to make Polish independence a reality.

The key to defeating the Russian invaders, Piłsudski realized, was the Pripet Marshes, a vast wilderness of wetlands along the forested basin of the Pripyat River and its tributaries. The marshes—generally regarded at the time as impassable—sliced the 600-mile-plus zone of battle into two almost separate sectors. One, by far the more dangerous, was the northern corridor, which led directly to Warsaw. But the southern corridor was also important, as it could enable potential Russian-hating allies in Ukraine and Byelorussia to join forces with the Polish army. The Bolsheviks had swarmed into Ukraine in the final months of 1919 and forced a “national” army led by Symon Petlyura to retreat to Poland.

Piłsudski decided that these Ukrainian soldiers and a nine-division Polish army should attack in the south and force two Russian armies into retreat. He struck on April 25, 1920. The Russians, taken by surprise, fell back. They were dismayed to find hundreds of Polish cavalry waiting for them. These horse soldiers would soon make the struggle for Warsaw radically different from the static trench warfare of the Western Front in World War I.

The two Russian armies did not muster more than 20,000 men; they were called armies only for lack of a more accurate term. The distances of the battlefield made it necessary to give them semi-independent status, with a general in command of each force. With Piłsudski’s men applying pressure from the front, the Polish cavalry in the rear produced near-panic. In two days the Russians were in disorderly retreat, throwing away weapons, packs, supplies. But the Polish cavalry were too few to force many of the Russians to surrender. Most, to Piłsudski’s chagrin, escaped to fight another day.

Adding to the Russians’ dismay, the Polish army was backed by armored cars and an air force—bombers that planted high explosives on roads and supply trains. Piłsudski had sent emissaries to several Western countries and they had responded with alacrity, appalled by what might happen if the Russians got to Germany. The French also sent a military mission of 300 officers to Warsaw. One of these professional soldiers was Major Charles de Gaulle, whose military and political fame awaited another war.

No one was happier with this victory over the Russians than the Ukrainians in Piłsudski’s army. They called for an immediate attack on the Ukrainian capital of Kiev. Hoping to create a grateful ally, Piłsudski agreed, even though he expected the Russians to fiercely defend the city. As his army crossed the border between the two countries, Piłsudski sent a cavalry division racing ahead with orders to gather information on the Kiev garrison. The following day their report produced joy and celebration. The Russians had fled with the disorderly remnants of the two armies that the Poles had already smashed.

In his headquarters confronting the northern corridor, Tukhachevsky seemed unworried by Piłsudski’s southern victories. The Russian commander remained confident that his troops, which he liked to call “a horde,” would prevail when they made their move toward Warsaw. But plans for the completion of the horde had to wait. Moscow ordered an immediate attack to take the pressure off the Ukrainian sector.

A WEEK AFTER KIEV HAD FALLEN TO THE POLES, Tukhachevsky followed through on the order from Moscow. His plan was to split the Polish armies in the north, and force two of them into the Pripet Marshes, where they could be destroyed at leisure. The Poles were taken by surprise and fell back at first. But the Russian army proved woefully inept at keeping pressure on them, giving the Poles time to organize a reserve army and counterattack within a week. Suddenly the Russians were retreating in a style that recalled the panic that had wrecked their southern front. Two cavalry regiments surrendered to a single troop of Polish lancers. The Polish generals in immediate command were inclined to keep going all the way to Moscow. But Piłsudski ordered them to call a halt and send him reinforcements for the southern front, where suddenly things weren’t going so well.

Aware that the world was watching, Lenin and Trotsky decided to erase the southern Polish victories. They were encouraged by the trouble Symon Petlyura, the Ukrainian leader, was encountering. While Petlyura was recruiting and training an army, the Russians confronting him had suddenly regained their confidence, thanks to reinforcements pouring in, and were making aggressive moves all along the front.

The transformation within the Russian ranks had everything to do with the arrival of the most fearsome cavalry unit in the war, led by a totally ruthless commander, Semyon Budyonny. The 1st Cavalry Army, or Konarmia (“Horse Army”), had been created a year earlier, when most of Russia’s famous horsemen, the Cossacks, had joined the conservatives in the civil war. Budyonny, a tsarist officer with a mustache even more extravagant than Piłsudski’s, had joined the Bosheviks in 1917, but the Communists had no illusions that he was loyal to them or anyone else. It fell to Josef Stalin, a rising Bolshevik star, to keep Budyonny in line as his political commissar. (All the Russian armies had commissars to make sure they followed the party’s orders.)

Stalin was immensely impressed by Budyonny and helped him build the Konarmia into a formidable force, with 4 cavalry divisions, 1 infantry brigade, 5 armored trains, and a squadron of 15 planes. Budyonny’s horsemen were not nice people. They killed civilians and prisoners. Budyonny began his attack on Kiev by probing for an opening between the two Polish armies that were defending the city. This was his standard tactic. Once he found an opening, he flung the full weight of his whole division at it and burst into the enemy’s rear, where his horsemen soon created chaos.

But this time Budyonny was in for a shock. Swiftly filling the gap were horsemen of the 1st Polish Cavalry Division. The Bolsheviks were so busy defending themselves that they were unable to inflict much damage on the Polish rear. Budyonny’s situation was not improved when a brigade of Cossacks switched sides, shot their commissars, and began attacking the Russians. Budyonny regrouped and attacked again two days later, on June 1. Once more he got nowhere. Finally, on June 5, the Konarmia burst through and began rampaging in the Polish rear. But the Polish cavalry continued to contest Budyonny’s progress and the fighting soon degenerated into small, almost pointless, clashes—brilliant as tactics for a book on cavalry history but accomplishing little. This gave the Poles time to evacuate their garrison from Kiev.

Finally recognizing Budyonny’s central role in Russia’s plan for the southern corridor, Piłsudski vowed to destroy him and assembled enough horsemen and infantry to do the job. He struck as the Konarmia’s leader was relaxing at the Hotel Versailles as his soldiers laid waste the town of Rowne and nearby villages, mercilessly massacring civilians in their usual style. After several days of ferocious fighting, Budyonny decided to retreat from the town. And just in time: An entire Polish infantry division had charged into the battle, with orders to capture or kill Stalin’s favorite general.

But the infantry division and other Polish troops received abrupt orders to break off the battle and retreat about 60 miles west to a new defense line. Piłsudski suddenly needed every man he could find to prevent ultimate disaster. Tukhachevsky, his army revived by massive reinforcements, had begun an assault in the northern corridor so that he would take Warsaw by the middle of August. Along with veteran infantry divisions hardened in the struggle with the conservative Russians, Tukhachevsky had acquired a cavalry corps led by one of the shrewdest, most exotic generals in the war, a Persian-born Armenian named Hayk Bzhishkyan, also known as Gai Dmitrievich Gai. He was much smarter than Budyonny, especially in the art of cooperating with infantry.

The Poles mustered about 80,000 men to confront the Russians. But they had to guard a 370-mile front, while the 120,000 Bolsheviks could choose where to strike with massed strength. Tukhachevsky’s proclamation on the day of the attack exuded confidence: “Soldiers of the Red Army! The time of reckoning has come. In the blood of the defeated Polish army we will drown the criminal government of Piłsudski. Turn your eyes to the west. In the west the fate of world revolution is being decided. Forward!”

Backing up this rhetoric, the Politburo in Moscow ordered the Russian secret police to escort a group of Polish Communists with orders to take over Branicki Palace in Białystok, the largest city in northeastern Poland. There they proclaimed themselves the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee and began publishing a newspaper that cheered the opening of Tukhachevsky’s offensive.

Russian artillery opened the battle with a ferocious barrage. One Russian army surged forward at the northern tip of the front, with orders to break through and then swing south, sending Gai’s men in the lead. But even his ferocity could do no more than dent the Polish line. Nevertheless, the danger of a collapse under pressure from other Russian armies remained real, and Piłsudski ordered another retreat. This did nothing for Polish morale. But his men made the trek and dug into new fortifications in German trenches left from the Great War.

Panic grew in Warsaw. Piłsudski’s critics attacked him, pointing to his lack of formal military education. A new government was patched together. It appealed to Britain and France for help, but they did nothing but propose a truce and peace talks, although some of their politicians and diplomats swarmed into Warsaw, supposedly to give advice. The French military mission included General Maxime Weygand, who during the war had served as chief of staff on the Western Front to Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander. They tried to win him Piłsudski’s job, but Piłsudski still had enough sway to make the supposed savior an assistant chief of staff.

Meanwhile, with Tukhachevsky using the spacious battlefield to maneuver around their flanks, the Polish armies continued to retreat. Things were not much better in the southern corridor. There, Budyonny’s cavalry, having recovered from its earlier setback, was forcing the Poles into constant retreat. Things looked so promising that Lenin wrote to Stalin to ask him if he should consider a revolution in Italy. “It would be a sin not to try,” Stalin replied.

But Piłsudski had other ideas. The only way he could withdraw troops he needed from the north, he decided, was by defeating Budyonny there. The Konarmia was growing weary and disillusioned with the Poles and Poland. Its soldiers had been told they would be greeted as liberators. Instead, the Poles kept shooting back. Poland itself had been sold to them as a land overflowing with bourgeois luxuries. Instead, after so many years of invasions, its towns and cities were mostly wrecks. When the horsemen discovered that the mansions of big landowners in their path were little more than looted shells, they expressed their disappointment by coating walls and floors and stairs with excrement. It became their calling card.

Piłsudski’s offensive against the arrogant horsemen was a startling success. The Poles, reinforced by two new cavalry divisions, refused to give way. They retreated and then counterattacked from Budyonny’s flanks. “The vermin are choking us!” Budyonny exclaimed.

The Polish cavalry blocked Budyonny’s retreat while two other armies challenged his shaken men on their front and flanks. For a day it looked as if the Konarmia would be shattered beyond repair. But the attackers were suddenly stymied by frantic orders from Piłsudski in the north. He needed every available man. Tukhachevsky’s men were about to breach the last line of defense before Warsaw.

In four weeks the Bolsheviks had advanced hundreds of miles without winning a single battle. A new kind of war was emerging as the generals took advantage of the vast distances of the battlefield. Tukhachevsky was in the process of again outflanking the Polish armies along the Vistula, the last natural barrier between him and Warsaw. Shifting the bulk of his forces north, he hoped to force another retreat that would enable the Russians to assault the capital directly. Tukhachevsky confidently predicted that Warsaw would be in his hands by August 14.

PIłSUDSKI REALIZED THAT HE HAD ONLY ONE HOPE of rescuing Warsaw: He had to take the offensive when and where he was least expected. Somehow, he managed to extract five divisions from the capital’s last-ditch defenders and position them to make the most daring move of the battle. Underscoring his awareness of the size of the risk he was taking, Piłsudski left Warsaw and took direct command of this unknown army. He even wrote out his resignation as Poland’s commander in chief, knowing how welcome it would be if he failed.

In Moscow the high command was growing uneasy about Tukhachevsky’s plans. They tried to persuade him to abandon his latest flanking movement. They urged him to swing south and place himself between the Polish army and Warsaw. But the field commander brushed aside their worries about exposing his southern flank. He curtly informed them that the southern army could and should handle this task.

On the southern front, Stalin turned an equally deaf ear to all orders from Moscow. He had been seized by a dream of conquest in another direction. He thought his armies would soon be in a position to capture Prague, Vienna, and Budapest. He fired off a telegram to Lenin, advising him to keep the politicians’ noses out of military matters. He threw in a sneer at Tukhachevsky, with his arrogant demands to protect his southern flank. The distances were too great, even for the hard-riding Konarmia.

Tukhachevsky, foolishly, was overconfident. One of his officers found a copy of Piłsudski’s plan and rushed it to his commander. Tukhachevsky dismissed it as a hoax and let two of his armies begin probing Warsaw’s defenders, dug in along the Vistula.

As Warsaw trembled at this intimation of doom, Piłsudski unleashed his five divisions, which were soon rampaging in the Russian rear, wreaking havoc on their plans and morale. He led the attack with three divisions under his personal command. They mustered 25,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry, all amply supplied with machine guns and artillery. Each division was told to act independently, and they proceeded to do so with vigor. Even Piłsudski was amazed by their progress. He would later say that he found it hard to believe the way his men were advancing across territory they had abandoned in their humiliating retreats only a few weeks ago.

Its soldiers already weary, the Red Army started to disintegrate. The defenders of Warsaw charged across the Vistula and joined Piłsudski’s men, turning the battle into a rout. On August 18 a staggered Tukhachevsky ordered a retreat. This only encouraged the exultant Poles. By August 25 they had driven back the Red Army 300 miles. The Poles captured 65,000 bewildered Russians, plus hundreds of artillery pieces and machine guns. Thousands of other fleeing Russians crossed the border into East Prussia and were interned. In Białystok, officials of the Provisional Communist government shut down their newspaper, packed up their personal belongings, and disappeared.

When Piłsudski returned to Warsaw, leaving his army with orders to continue their advance, he expected cheers and congratulations. But few people in the capital believed the stories they were hearing from the front. One who had the background to know what had happened was Charles de Gaulle. “Our Poles have grown wings,” de Gaulle wrote in his diary. “The soldiers who were physically and morally exhausted only a week ago are now racing forward in leaps of 40 kilometers a day. Yes, it is Victory! Complete, triumphant Victory!”

Sporadic fighting continued. At one point the disbelieving Moscow Politburo, seemingly unaware that their provisional government in Białystok had vanished, issued a statement urging Poles to lay down their weapons and join the revolution. Tukhachevsky continued to add fresh men to his army, confident he could resume the offensive. But these spates of optimism soon evaporated. Tukhachevsky discovered that whole armies had disappeared from the battlefront. Meanwhile Piłsudski’s soldiers wheeled and flanked in seemingly unbeatable maneuvers, inducing still more panic in the Russian divisions.

In October, under pressure from France and Britain, both sides agreed to an armistice. On March 18, 1921, they signed a peace treaty establishing an independent Poland. Lenin and Trotsky abandoned their vision of a Communist Europe. Instead, they declared, they would devote themselves to creating “communism in one country” that would serve as an example to nations everywhere.

Poland remained a vital democracy until 1939, when Russia greedily joined the Germans in invading it and seizing most of the eastern half of the country. This was one of Stalin’s most egregious mistakes, as he soon realized that Russia was Adolf Hitler’s real objective. Tukhachevsky and many of the subordinate generals who had fought in the Battle of Warsaw had been murdered in Stalin’s paranoid purges of the 1930s. Among Communist leaders, Stalin was the one most disappointed by the failure of the Army of the West.

Józef Piłsudski died in 1935 of natural causes and remains revered in Poland. This year he will be especially commemorated on the 150th anniversary of his birth. The other nations of Eastern Europe might well remember him, too. The 20 years of freedom created by the Battle of Warsaw helped them to survive the dark night of Soviet communism that engulfed them at the close of World War II. The memory played a strong part in the vigor with which they repudiated Lenin’s evil concoction after it collapsed in Russia in 1989. Once more, Poland played the lead in this drama of unforgotten freedom. Those declarations of independence more than vindicated the several historians who had judged the Battle of Warsaw to be one of the most important military confrontations in the world’s turbulent history. MHQ

THOMAS FLEMING is the author of The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I and The New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War Within World War II. He has also written many books about the American Revolution.

[hr]

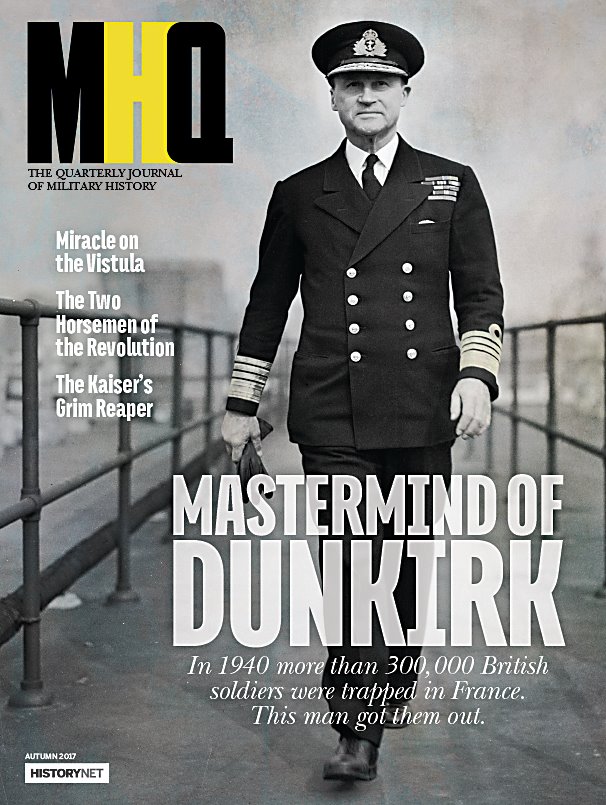

This article appears in the Autumn 2017 issue (Vol. 30, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Miracle on the Vistula

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!