Believing they were secretly working for Germany, members of a subversive “fifth column” were actually the targets of an extraordinary British intelligence operation.

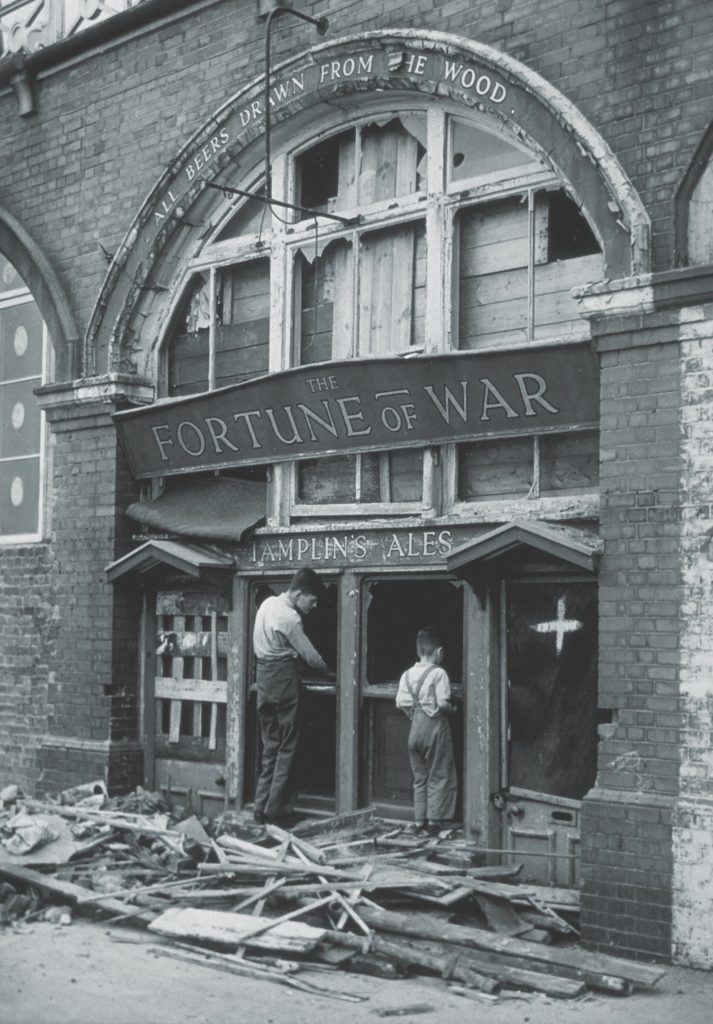

IN APRIL 1943, Nancy Brown sat down with three friends in a London apartment to describe a German bombing raid she had witnessed a few weeks earlier in her hometown of Brighton, on England’s south coast.

“Someone said: ‘Oh, look at those planes,’” she explained, “and they looked out to sea and saw some big black planes flying in over the top of the water—couldn’t hear a sound—and just as they got to the end of the pier they seemed to turn their engines on and they flew straight up like that, branched out, and started machine–gunning and cannon–firing and dropped a lot of bombs!”

This was a “tip-and-run” raid, when Luftwaffe fighters would fly in from France below the British radar, strafe coastal towns, and then get out before the Royal Air Force could scramble to take them on.

Brown, a fresh-faced woman in her early twenties, had been in a café when the raid started. “I’d no sooner sat down in Ward’s to have my coffee when suddenly: ‘Crack! Crack! Crack!’ And everybody dived to the back of the shop because they felt quite sure the bullets were coming in at the windows and we were all huddled together,” she said. “And then Boomp!”—she banged the table—“Boomp! Boomp! And the windows blew in and out and the doors blew in and out. And when we came out we could see great columns of smoke coming up.”

Attacks like this were quite common at this stage of the war. What made Brown’s experience unique was that she thought the German bombing raid was the result of her work. Nancy Brown believed herself to be a Nazi informant. She had been recruited by the two women with her, and they reported to the man whose apartment they were in, Jack King.

We know what Nancy Brown said because she was one of the targets of an extraordinary British intelligence operation. “Jack King” was, in reality, Eric Roberts, a 35-year-old Englishman and married father of three who lived in the pleasant commuter suburb of Epsom, southwest of London. Until 1940, he had been a clerk at Westminster Bank and a source of some frustration to his employers, who found him altogether lacking in seriousness.

What Westminster Bank didn’t know was that since his teenage years, Roberts had been living a double life as an agent of MI5, Britain’s domestic security service. He had spied on communist groups in the 1920s, and in 1934 had become MI5’s first man inside the British Union of Fascists (BUF), the political party led by the charismatic and outspoken former member of parliament Sir Oswald Mosley. After the outbreak of war and the banning of the BUF, Roberts had joined MI5 as an officer, with the job of hunting for a subversive “fifth column” of fascist sympathizers in Britain who were waiting to rise up and support a Nazi invasion.

THERE WAS NO QUESTION in anyone’s mind in 1940 that such a fifth column existed. It was an article of faith that similar groups in other countries contributed to Germany’s rapid advance across Europe. Britain’s ambassador to Holland, Sir Nevile Bland, who had barely escaped before the country surrendered, reported to Winston Churchill that victory had been handed to the Nazis by a network of spies, many of them Germans working as domestic servants. “The paltriest kitchen maid,” he wrote, “not only can be but generally is a menace to the safety of the country.”

Bland’s memo had helped spark hysteria, with people arrested simply for having German-sounding names. Actual Germans were rounded up and held in camps (as were Austrians and Italians), even though many were in Britain because they were fleeing the Nazis. Throughout that year, MI5 was overwhelmed with tip-offs, almost all of them bogus. But by the end of 1941, the spy-hunters had reached a conclusion: Germany had no organized network of spies in Britain. German intelligence didn’t seem to have given much thought to the idea that it might find itself fighting a long war with Britain and had done little to establish any deep network there. Much of the information that might have been wanted in areas such as industrial capacity was freely available in Britain’s open prewar society.

But even if MI5 couldn’t find a fifth column, it did keep finding people who wanted to join one. There were plenty of British people who didn’t understand why they were at war with Germany. Like Nancy Brown and her friends, they liked the look of what Hitler had done to his country, bringing order with strong government and seeing off the communists. And they hated Jews, believing they used their money and connections to cheat others, and admired the Nazis’ treatment of them. They would welcome a negotiated peace and an alliance with Germany against the Soviet Union.

All of this was on the mind of a man who had a good claim to be MI5’s most glamorous officer. He was certainly its richest. Victor Rothschild had a seat in the House of Lords and was the heir of the English branch of the family bank. Thirty-one years old, he seemed to enjoy every blessing. Not only did he have limitless money, but he also had good looks, with a sweep of dark hair matching his dark eyes, and was a skilled cricketer as well as a brilliant scientist—a microbiologist working at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Rothschild was also Jewish and, because of that, had at least once been refused service in a British restaurant. But more than that, he and his family were to many the ultimate example of Jewish power. Victor knew that he and his young children were at the top of Nazi arrest lists if Britain fell, and he was determined to do whatever he could to stop that from happening. “He is quite ruthless where Germans are concerned,” noted the man who recruited him into MI5 at the start of the war, “and would exterminate them by any and every means.”

Rothschild’s official job was counter-sabotage. That meant understanding the mechanics of the bombs that Germany was placing onboard ships carrying supplies destined for Britain from Spain and Gibraltar. These were often ingeniously disguised as pieces of coal or bars of chocolate, or placed in a vacuum flask, hidden under an inch and a half of hot tea.

To learn about how they worked, Rothschild sought examples of bombs that hadn’t gone off and then took them apart. It wasn’t a job for the nervous: he went to work on the first one well aware that the last person to attempt to take that model apart had lost an eye and an arm when it exploded. Hoping to save at least his eyes, Rothschild performed the operation while kneeling behind an armchair.

He quickly found he was adept at the task: his years of dissecting frog and fish eggs while studying biology at Cambridge University had given him a steady hand. The jeweler Cartier, who valued him as a customer, gave him a special set of small screwdrivers; he recruited a young artist, Laurence Fish, to diagram the bombs’ workings. But his mind was on more than explosives and fuzes. Rothschild was worried about the depth of secret British support for Hitler, and he had an idea about how to discover it.

If there was no genuine fifth column, why shouldn’t MI5 set one up and see who joined it?

FOR MOST OF 1941, Rothschild had worked with Eric Roberts searching for German spies in the British arm of Siemens, the giant manufacturing company headquartered in Munich that produced everything from electric meters to telegraph equipment. They hadn’t found any, but in the course of his work, Roberts had come into contact with a remarkable woman.

Marita Perigoe, 27, was the daughter of Australian composer May Brahe, author of the beloved inspirational ballad “Bless This House.” Born and brought up in London, Perigoe had become a dedicated fascist. Her husband Bernard shared her views and was then interned on the Isle of Man for trying to organize support for fascism. MI5 knew little about Perigoe, but Rothschild and Roberts quickly realized she was far more dangerous than her husband.

“She is a masterful and somewhat masculine woman,” they wrote in a case summary for their superiors at the agency. “Both in appearance and mentality she can be described as a typical arrogant Hun.”

Perigoe was determined to do whatever she could to help Hitler win the war. In her, Rothschild saw a danger—but also an opportunity. “A woman of this type, with so much misdirected ingenuity, might do great harm,” he wrote, “unless she were controlled.”

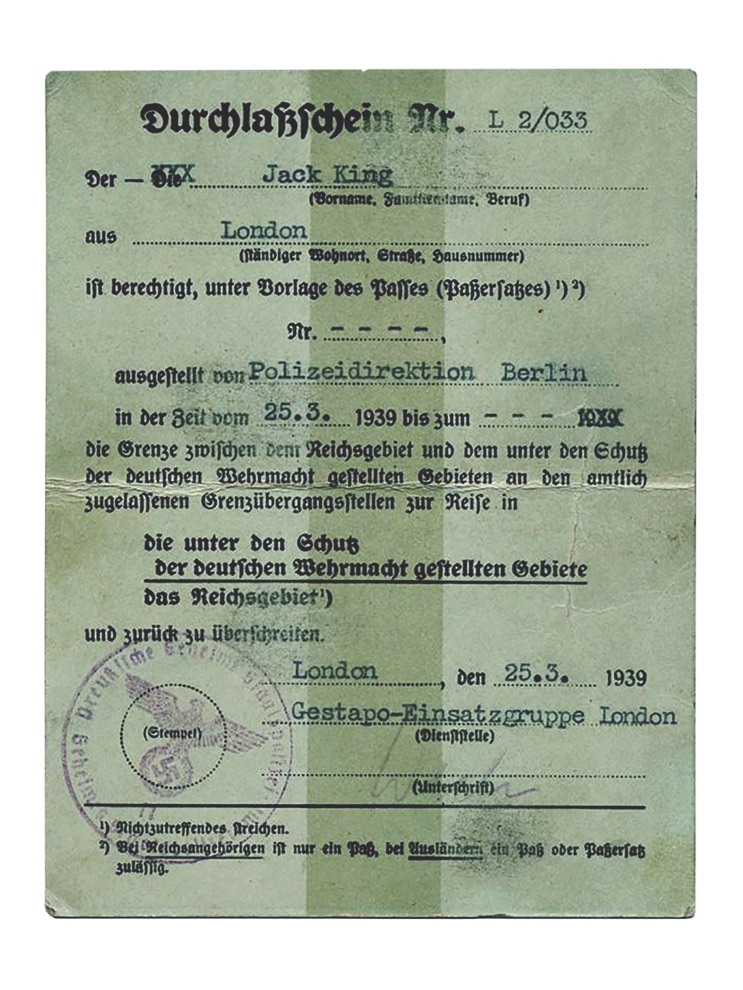

So he gave her a controller. In early 1942, Roberts, who had met Perigoe under the identity of “Jack King,” told her that he was a Gestapo operative, tasked with identifying people who might be willing to help Germany in the event of invasion. He showed her a pass, faked for MI5 by their colleagues at the foreign intelligence service MI6. He didn’t claim to be German—simply an Englishman loyal to the Nazi ideal, as she was.

MI5 initially arranged a room for Roberts to meet his recruits in the basement of an antique shop on Marylebone High Street in London’s West End—Rothschild noted that the aspiring traitors had “certain somewhat melodramatic ideas”—but after a few months, they shifted the location to a more comfortable apartment in West London. There it was wired up with a bug, most likely planted in the telephone that sat on the table. Every word spoken was recorded onto 12-inch cellulose disks and then transcribed. Hundreds of pages of those transcripts now sit in Britain’s National Archives at Kew in West London.

From its beginning, the operation was controversial among the small number of MI5 officers aware of it. At the start of the war, the service had recruited many lawyers and academics, who brought with them more liberal instincts than were usually found in a security service. These men took a dim view of “provocation”—undercover policemen encouraging people to commit crimes and then arresting them. It was not a very British way to behave. More than that, they warned that the courts would object, making any evidence Roberts gained inadmissible.

But Guy Liddell, MI5’s head of counterespionage, agreed with Rothschild. Just shy of 50, Liddell was a thoughtful, gently humorous man whom the staff admired for his wisdom. He felt it was important to find out how many potential Nazi supporters there were. Two years earlier, Nazi landings had seemed imminent. In 1942, Germany was too busy elsewhere to attempt an invasion of Britain—but what if the situation were to change? “We must I think regard the whole situation in the light of a collapse on the Russian front, ourselves driven out of the Mediterranean and 200 German divisions brought back to the West,” he wrote in his diary. “In such an eventuality, how should we be feeling about the 60,000 enemy aliens at large in this country and other subversive bodies?”

Liddell’s problem was one faced by secret police through the ages: testing hidden loyalties. “We knew the man who waved a swastika flag in the street, the man who waved it in his back garden and was seen by his neighbours, but did we know one who waved it inside his own house?” Liddell wrote. He argued that there was no use being squeamish about civil liberties in a time of war, telling a colleague that “we might not like anything that savoured of agents provocateurs, but such methods were necessary in times of crisis.”

Liddell was aware, however, that the Home Office—the government department that oversaw MI5—was already worried about the way the spy-hunters were behaving in wartime: trying to get suspects locked up simply on the basis of their suspicions, or on the evidence of a single, sometimes doubtful, witness. This was exactly the sort of operation that would outrage the Home Office. He solved the problem by not telling them.

In 1943, worried that it didn’t have enough supporters in government, MI5 began sending Winston Churchill monthly reports on its activities. The prime minister delighted in tales of the “Double Cross” operation, where captured spies in Britain were used to supply false information to the Nazis, and particularly in the activities of Eddie Chapman, better known as Agent Zigzag: a former safe-cracker who at different points worked for both Germany and MI5. But a conscious decision was made to leave out mention of counter-subversion operations like the one Rothschild was running with Eric Roberts. Liddell didn’t think Churchill would disapprove, but he feared the prime minister might mention something to the Home Secretary, who was being kept out of the loop.

Roberts, meanwhile, was getting on with building his network. It was going even better than he and Rothschild had hoped—or feared.

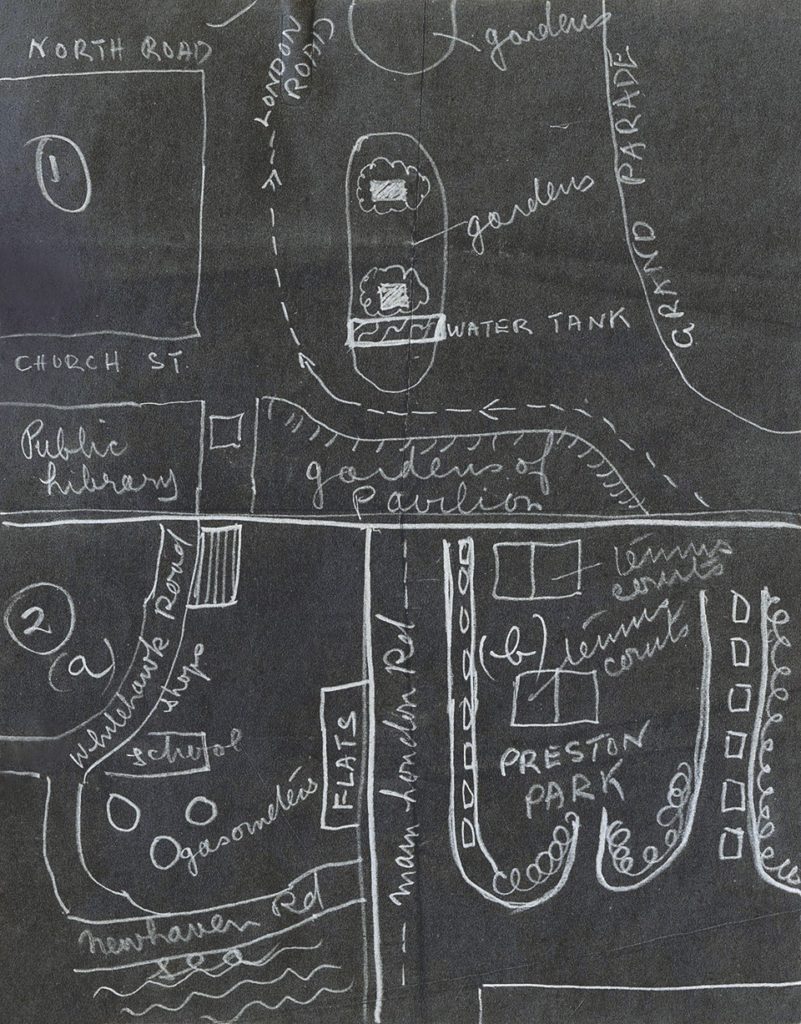

Marita Perigoe was proving to be an outstanding recruiter. A case summary by Rothschild in July 1942 listed 17 of the “more interesting” people Perigoe had brought in. Many were women, people she knew from her middle-class neighborhood of Harrow, in West London. There was Eileen Gleave, who “would, in time of invasion, be prepared to raid the Wembley Home Guard arms depot in order to assist the enemy.” Hilda Leech worked as a clerk at the oil company Shell Mex and began providing weekly updates on the amount of petroleum stored around the country. And there was Nancy Brown, who drew maps to show the location of Brighton’s defenses, and pledged to guide an invading force around them.

Probably Perigoe’s greatest recruit, though, was Hans Kohout. Austrian by birth, Kohout had moved to Britain a decade earlier and was an expert in the manufacturing of aluminum foil. In his late 30s, with a thick accent he never managed to shake, he had escaped internment at the start of the war both because this knowledge was valuable to the war effort and because he had obtained British citizenship. His loyalties, however, were very much divided. In the summer of 1939, his Austrian-born wife and his infant son had traveled to Austria for a vacation. Kohout joined them for a couple of weeks and then returned to London for work. His wife had stayed on with her parents, probably enjoying having some help with childcare. When war broke out at the start of September, she was trapped, only able to communicate with her husband via infrequent letters passed on by the Red Cross.

Kohout, therefore, found himself living in a country that was dropping bombs on his wife and son. Worse, he was helping: the factory where he worked had a number of secret military contracts. So when Perigoe approached him and asked if he would like to work for the other side, the offer held an immediate appeal. It wasn’t just about feeling he was doing something for his family and the country of his birth: Roberts’s recruits got to experience the thrill of living a secret life. “Once one becomes conscious, one becomes sort of…brighter,” Eileen Gleave told Nancy Brown. They were spies, part of the same world as everyone else, but now aware of a different level of it—a place of secret communications and clandestine meetings.

Kohout, in particular, was very good at it. Within months of being recruited, he had brought Roberts details of Britain’s new fighter-bomber, the de Havilland Mosquito, which he had obtained from a drunk employee of the company making its flight instruments, and information about a prototype jet.

At first, Roberts tried to discourage his recruits from gathering intelligence in an effort to stay on the right side of the “provocation” line. But their determination to do something was such that Rothschild concluded that letting them spy was preferable to their alternative proposal: carrying out acts of sabotage. This had to be continually forbidden. As D-Day approached in 1944, the group even discussed whether it would be possible to kill General Dwight D. Eisenhower. It was a plan that Roberts hastened to reject. He was learning that the life of an agent-runner—even a fake one—was a lot of hard work.

Kohout’s greatest coup came in 1943 when the Air Ministry approached his employer and asked if it could manufacture strips of foil to precise specifications. The purpose wasn’t explained, but it was for Britain’s “Window” system (known as “chaff” to Americans): a top-secret technology that used strips of foil to fool German radar about the location of Allied bombers.

“Kohout has hit upon something which is considered to be one of the most secret and hush-hush devices so far developed in the U.K.,” Rothschild reported on May 4, 1943. “It is obvious that the slightest leakage of it to the Germans would put them in a very strong position.” But while the Austrian had a credible claim to be the best spy that Nazi Germany had in Britain during the war, his tragedy was that none of his reports made it any closer to Berlin than MI5 headquarters.

Kohout’s success created new problems. Perigoe, having brought him into the group, now became jealous of him. She tried to undermine him, and Roberts had to start meeting the pair separately. Perigoe never totally trusted “Jack King” either. Every so often she would remark that he might be an MI5 man, and say that she would cut his throat if she found out that he was. Roberts didn’t doubt her seriousness.

AS THE END OF THE WAR approached, MI5 faced a new problem. The number of fascist sympathizers on Roberts’s books had grown to around 500—a huge number, considering that the operation was based on one man simply making himself available. The vast bulk of those individuals were simply people whom Roberts’s more active recruits had identified as possible supporters—but even if MI5 looked only at the people actually working with Roberts in the belief that he was a Nazi spy, they had identified some 20 willing traitors. What should it do with them all?

One option was to put them on trial. People had been jailed for much less, and a conviction for treason carried the death penalty. But that would mean revealing the operation to, among other people, the Home Office, where there might be questions about why they hadn’t been informed about it.

Besides, MI5 didn’t know who its next enemies would be. The operation was continuing to provide useful intelligence about underground British fascist movements. And through his recruits, Roberts was plugged into all of them. Why not just let it run?

So it was that January 1946 saw one of the oddest ceremonies relating to the war, as Eric Roberts, in his guise as Jack King, presented Marita Perigoe and Hans Kohout with the Kriegsverdienstkreuz 2. Klass—War Merit Cross, Second Class—ostensibly on behalf of a grateful, if defeated, German government. The recipients were, Liddell recorded in his diary, “extremely gratified.” Perigoe said she would hide hers in the stuffing of her armchair. Roberts now claimed to be representing an underground network dedicated to continuing the Nazi struggle and asked the pair to continue supplying him with information.

In the years that followed, it quickly became clear that the main threat to British security was communism, not fascism, and the operation tailed off. Marita Perigoe and Eileen Gleave both moved to Australia. Kohout, reunited with his family, went into business—with a Jewish friend. They and the rest of the would-be spies went to their graves thinking they had a great secret—that they had spent the war working for Hitler—while unaware of the greater one: that they had been dupes of MI5.

In 1947, Roberts was loaned to MI6 for an unsuccessful operation in Vienna. When he returned, MI5 was seeing traitors everywhere in the wake of the discovery that there had been Soviet agents at the heart of British intelligence since before the war. Feeling sidelined and mistrusted, he moved his family to Canada in 1956.

Hans Kohout died in 1979. Going through his things, his grandson, Ernest Kohout, found a small red leather box containing a Nazi medal and asked his mother what it was. Though she knew the truth, she replied that it had been given to his grandfather as a mark of his long service on the Austrian railway.

Amused, Ernest hung the medal on his bathroom wall. ✯

This article was published in the April 2021 issue of World War II.