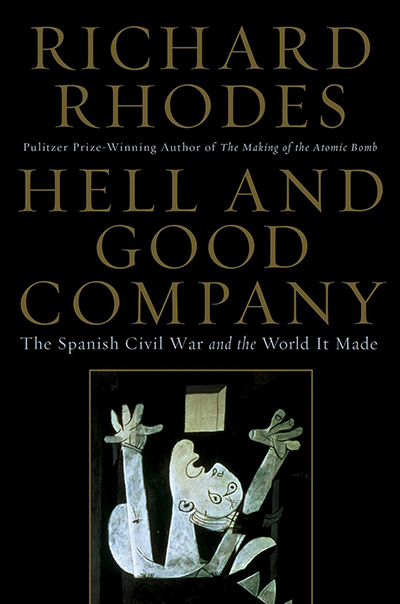

Hell and Good Company

Life and Love in the Spanish Civil War

by Richard Rhodes. 384 pages. Simon & Schuster, 2015. $30.

Reviewed by Peter Carlson

“Many books have been written about the Spanish Civil War. Few of them explore the aspects of the war that interest me,” Richard Rhodes writes in his preface to Hell and Good Company. Rhodes says he was drawn to the “human stories that had not yet been told or had been told only incompletely,” and he has woven those stories into a fast-paced and ultimately moving book.

Rhodes, 77, is one of America’s finest writers of narrative nonfiction. Best known for his four books on the history of nuclear weapons—including the Pulitzer Prize–winning The Making of the Atomic Bomb—he has also written a biography of John James Audubon, a memoir of his own Dickensian childhood, and more than a dozen other books. He is a master of the art of weaving several stories and complex background material into a compelling narrative, and he demonstrates that art in this book.

Rhodes quickly sketches the background of the Spanish Civil War—how after centuries of rule by the aristocracy, the army, and the Catholic Church, Spain finally became a republic in 1931. Five years later General Francisco Franco led a military revolt against the republic. Mussolini and Hitler aided Franco with troops, arms, and air power, while Stalin sold guns to the republican forces, which were reinforced by 40,000 foreign volunteers, many of them Communists.

Against this backdrop, Rhodes tells the stories of a handful of foreigners who traveled to Spain to support the republican forces—Norman Bethune, a Canadian surgeon; Edward Barsky, an American doctor; Patience Darton, a British nurse; Ernest Hemingway and his mistress (and future wife) Martha Gellhorn, both of whom reported on the war; and Robert Merriman, a Communist from California who led the American volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion and became a model for the hero of Hemingway’s war novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. The war changed their lives: Some fell in love, some were killed, and some were betrayed by their allies or jailed by their countrymen.

Two aspects of the war fascinate Rhodes—its effect on medical science and its influence on modern art. He chronicles how doctors, Spanish and foreign, pioneered new techniques for wound care while working under horrendous combat conditions. And he recounts in gruesome detail the German and Italian bombing of the Basque town of Guernica. Then he depicts, step-by-step, how Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, enraged and inspired by newspaper photos of the massacre, created his masterpiece—the starkly powerful 25-foot-long, black-and-white mural Guernica.

But even the greatest art could not save the Spanish republic from the overwhelming air superiority provided to Franco by Hitler’s Condor Legion. In April 1939 Franco won the war and created a dictatorship that ended only when he died in 1975. Rhodes’s book is not a full military history of the conflict, but it is an entertaining, if somewhat eccentric, introduction to what he describes as “a small but pivotal war at a hinge of history.”

Peter Carlson often focuses on personal stories to capture larger moments of history, as in his most recent book, Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy.

MORE WINTER 2015 REVIEWS

.jpg)