Among the ironies of the bloody and transformative Great Sioux War of 1876 is the differing manner in which Indian survivors—Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyennes, Shoshones and Crows—embraced its legacy and recalled its battle grounds. The twist is no more apparent than in the story of the June 17 Battle of the Rosebud, a sprawling fight involving all of those tribes and occurring just eight days before the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Emotions were mixed among the Army’s Shoshone and Crow scouts. The Shoshones fought alongside Brigadier General George Crook’s soldiers on the Rosebud, then quit the war and rarely looked back. After all, the Sioux war on the northern Plains was a world apart from the Shoshones’ Wind River homeland in Wyoming Territory. For the Crows proximity proved confounding. The Little Bighorn clash, the most heralded of the scores of engagements, was fought within the very bounds of the massive Crow Indian Reservation in Montana Territory. Crow warriors scouted for Crook, Brigadier General Alfred Terry, Colonel John Gibbon and Lieutenant Colonel George Custer in 1876, but by stance and proximity they have ever after been linked to the Custer story and its aftermath.

However ambivalent but understandable the Crow embrace of the Great Sioux War, their attachment to it was not shared by surviving Sioux warriors and their descendants. For one, the Sioux do not live in the midst of the war’s major battlefields. Rather, most live on reservations hundreds of miles east in the Dakotas. Moreover, their historical attention is largely focused elsewhere. In the immediate wake of the conflict some sought exile in Canada with Sitting Bull and Gall, while others, including those aligning with Crazy Horse, surrendered at agencies in Nebraska and Dakota Territory. Both courses were troublesome. The Canadian exile ended fitfully on July 19, 1881, when Sitting Bull surrendered at Fort Buford, Dakota Territory—the last of his tribe to do so. Crazy Horse, meanwhile, was bayoneted to death at Nebraska’s Camp Robinson on Sept. 5, 1877, during the Army’s botched attempt to arrest and remove him to Florida. For the rest of the surviving Sioux those early postwar days at the agencies proved little more than cycles of privation and humiliating land cessions. While the Sioux do recall Custer and the war for the Black Hills, their primary historical focus is on Wounded Knee, the Dec. 29, 1890, epilogue that proved far more horrific than anything occurring 14 years earlier.

Northern Cheyennes embraced the Sioux War differently yet. The war burdened them greatly, in attacks on Cheyenne villages on the Powder River in March and on the Red Fork of the Powder that November, and in the post–Little Bighorn clash with soldiers at Warbonnet Creek that July. Exiled to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) after the war, they made a desperate return trek north, only to be bloodied again in 1878 when some broke from imprisonment at newly christened Fort Robinson. When the U.S. government finally opened a reservation for the Northern Cheyennes in Montana Territory in 1884, those steadfast allies of the Lakotas found themselves smack in the midst of the Sioux war battlefields. The site of the war’s final clash—the May 7, 1877, Muddy Creek or Lame Deer fight—was almost immediately built over by the growing community of Lame Deer, tribal headquarters of the new reservation.

As had the Crows, the Northern Cheyennes also reckoned with Sioux war landmarks and battlefields in their very backyard. While vestiges of the Muddy Creek fight have all but disappeared, just north of Lame Deer stand the revered Deer Medicine Rocks, a site with spiritual significance to the war. Several miles north is the site of Sitting Bull’s mystical Sun Dance camp. Both overlook the historically sublime Rosebud Creek, an otherwise unassuming watercourse that threads its way across the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation south to north, its waters bound for the Yellowstone River.

Another postwar phenomenon with lasting resonance were the many interviews conducted with survivors. With an eye to preserving history, such interlocutors as Walter Mason Camp, Eli S. Ricker, Hugh L. Scott, Thomas Bailey Marquis, John Stands in Timber and others sought out participants and eyewitnesses—Indian and white alike—and recorded their stories. The Little Bighorn invariably dominated many accounts, but some veterans, particularly Indians, could not relate their involvement in that great fight without first acknowledging earlier episodes, stretching back to the saga of Northern Cheyenne Chief Old Bear and the Powder River fight at the outset of the months-long conflict. Much is owed to the interviewers, interpreters and aged veterans who so willingly shared their accounts of victory and defeat. Subsequent generations are forever enriched by their collaboration. The stories from the Rosebud are illustrative.

As proximity ties the Crows inexorably to the Little Bighorn, the Northern Cheyennes are similarly linked to the Rosebud, a sprawling battleground within miles of their reservation’s southern border. Northern Cheyenne affinity for the Rosebud has several roots. Around the turn of the 20th century their ancestors placed rock memorials on the battlefield to commemorate memorable encounters. They placed one such cairn in a feature known as the Gap, on the east side of the field, to honor a young warrior slain there. As the story goes, the boy’s bereft brother took a suicide vow in honor of his sibling and was killed in the fighting on the Little Bighorn eight days later. Unfortunately, the cairn was lost to time when that corner of the Gap was transformed into a hay meadow.

The Northern Cheyennes also placed stones where Captain Guy V. Henry was shot in the face, fell from his horse and barely survived the fight. Henry’s grievous wounding occurred on the southern shoulder of Kollmar Creek, an intermittent drainage that slices conspicuously across the battlefield. The Cheyennes and Sioux nearly destroyed the troops fighting with Henry and his battalion commander, Lt. Col. William B. Royall, thus the surviving cairn also serves as a stark memorial to a critical fight nearly won.

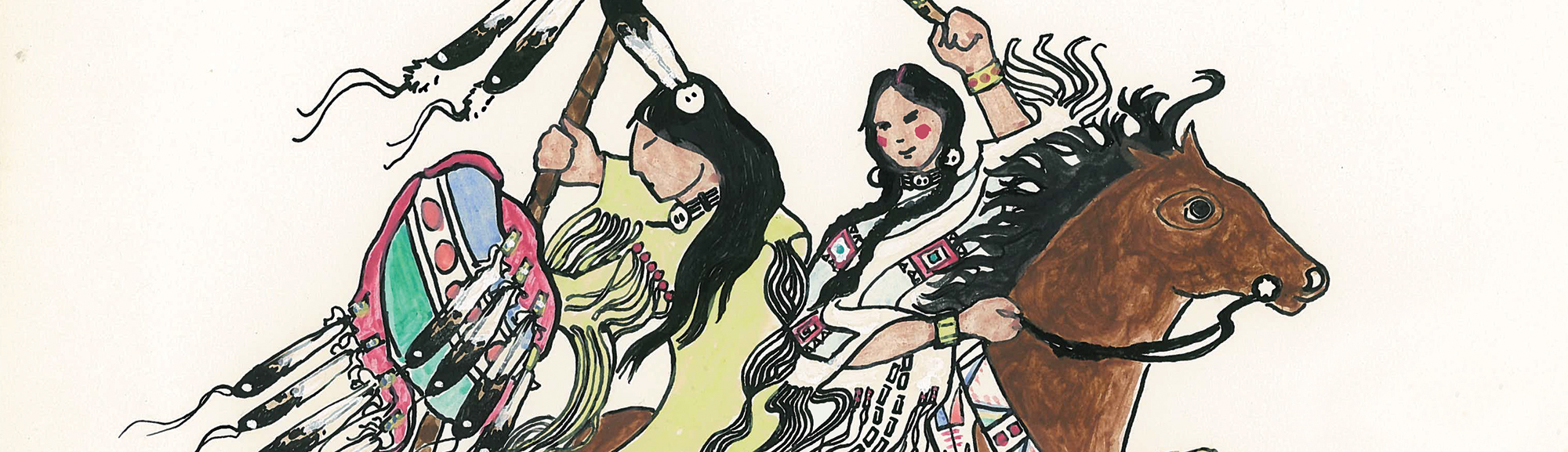

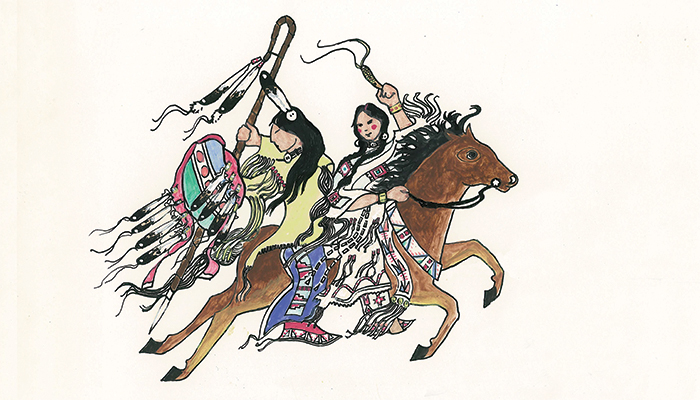

Among other heroic episodes occurring during the Rosebud battle, none is as dramatic as the moment a sister saved her brother. Early in the fighting in the Gap three warriors—two Cheyennes and a Sioux—were riding through the draw, perhaps as a test of courage or just as likely seeking to capture cavalry horses secured behind imposing rocks. The three faced harsh enemy fire, and as they turned back, one of them, a Cheyenne named Chief Comes in Sight, was thrown when a bullet shattered his horse’s hind leg, sending it into a somersault. Chief Comes in Sight landed on his feet and started to run, zigzagging to avoid incoming rounds. Soldiers went after him. Another mounted Cheyenne, White Elk, was preparing to draw the soldier fire and help his friend escape when he spotted a slender figure on horseback, racing down from the Indian lines straight for the dismounted warrior. When the female rider reached the man afoot, she wheeled her horse about, he jumped on behind her, and the two galloped off. Only then did White Elk recognize Buffalo Calf Road Woman, the Cheyenne wife of warrior Black Coyote and sister of Chief Comes in Sight. Amid a rain of bullets sister and brother escaped unharmed. But for his sister’s dauntless courage, Chief Comes in Sight surely would have been killed.

Chief Comes in Sight’s rescue was as honorific as it was startling. Buffalo Calf Road Woman was the only woman who rode from the Indian village that morning to confront Crook. The 26-year-old mother of two was a superb horsewoman and fearless warrior. By virtue of their very presence in Old Bear’s village on the Powder River that March, she, husband Black Coyote and brother Chief Comes in Sight had been drawn into the Great Sioux War. Buffalo Calf Road Woman fought again, on the Little Bighorn, but the Rosebud was her signature moment. For generations since her heroics have inspired Indian artists to render the scene, from period ledger art to modern fine art. While Crook claimed victory on the Rosebud because his troops occupied the battlefield at the end of the day, Northern Cheyennes recall it as Indian victory, namely as the “Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.”

Another episode in the Gap, while far less valorous, was telling in another regard. Jack Red Cloud, the 18-year-old son of Oglala Chief Red Cloud, had joined Sitting Bull’s confederation that May, just before the Sun Dance. Early in the Rosebud fight Crow scouts shot Jack Red Cloud’s horse from beneath him. (The young man was conspicuously, if foolishly, wearing his father’s eagle feather warbonnet and carrying an ornately engraved Winchester rifle that had been presented to his father at the White House a year earlier.) Thrown to the ground, Jack did not pause to remove the bridle from his dead pony—an act of righteousness expected of warriors, even in the face of deadly enemy fire. Instead, the frightened young man immediately took off running, his flowing warbonnet drawing inordinate attention.

Alerted by the flurry of feathers, several Crow scouts spotted Jack. One of them, Bull Doesn’t Fall Down, singled out the fleeing youngster as particularly worthy of a coup. Running him down on horseback, Bull Doesn’t Fall Down flogged Jack severely with his quirt, berating him as a coward for both failing to remove his bridle and bolting in panic, then further admonishing the teen for wearing the feathers of a true warrior. Young Red Cloud wept and begged for mercy. Bull Doesn’t Fall Down and fellow warrior Along the Hills confiscated the young Oglala’s warbonnet and rifle, then, in an eloquent expression of contempt, let him go. It was a humiliation worse than death.

At that point Crazy Horse and two others charged in to pick up young Red Cloud. Jack and his father were members of the influential Bad Face band of Oglalas, people deeply committed to preserving the old ways. Crazy Horse’s friend and fellow warrior He Dog was also a member of the band, and looking out for one another, even in such a humbling circumstance, was a critical virtue. Still, none of Jack’s saviors would look at him afterward, shaming him for having dissolved in tears before his enemies.

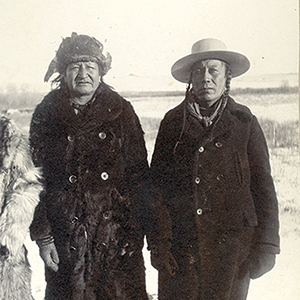

Jack Red Cloud’s humiliation on the Rosebud had an epilogue. In 1926, amid events marking the 50th anniversary of the Little Bighorn fight, aged Indian veterans held their own gathering at the Crow Agency. Present among the Sioux contingent from Pine Ridge was 68-year-old Jack Red Cloud, who by then was an Oglala chief. Also in attendance was Crook scout Bull Doesn’t Fall Down, the contemptuous Crow who had counted coup on Jack and openly berated him for his feckless behavior in 1876. Noticing Jack across the broad camp circle, Bull Doesn’t Fall Down walked briskly up to him, pulled out a quirt and in plain sight of all playfully flogged the dignified and thoroughly startled old Sioux chief. Jack sat still and proud, enduring the jest with no outward signs of humiliation or anger. Onlookers were puzzled until Bull Doesn’t Fall Down explained their encounter 50 years earlier on the Rosebud. The Crow then graciously summoned forth a buggy full of gifts and presented them to Jack. The two shook hands, Jack exclaiming, “Aho! Aho!” (“Thank you! Thank you!”) to the warm approval of his fellow Lakotas. At least these Crows and Sioux were enemies no more.

As in the Gap, the action on Kollmar Creek occasioned several distinctive episodes, perhaps none more thrilling than the escape of 18-year-old Cheyenne warrior Limpy. During some childhood escapade the young warrior had broken his leg, compensating ever since for bones that had been poorly set—hence his name. Regardless, Limpy fought as fearlessly as any other warrior on the Rosebud.

That morning to the south of Kollmar Creek, as a group of soldiers withdrew eastward afoot, Limpy and five other mounted Cheyennes pressed the bluecoats. Eager to count coup, they paid little heed to their surroundings. Suddenly a group of soldiers popped up on their left flank, firing as they advanced. The Cheyenne riders elected to make a run for a hill some 200 yards to the rear, warrior Young Two Moon suggesting they should scatter, so as to avoid making one big easy target. One by one each rode off, safely evading the soldiers. Then came Limpy’s turn.

The youngest in the group, he obligingly went last and had barely set out when a bullet struck his pony. The horse went wild, kicking, jumping and finally bucking off its rider, before dropping dead. Fortunately for Limpy, nearby stood a cluster of sandstone monoliths, some as tall as a man, others high as a horse, and all providing good cover on an otherwise exposed ground. Making for the rocks, the young warrior had just reached their shelter when he thought of his bridle, a fine one mounted with silver dollars that an uncle had given him. Unwilling to bear the shame of losing it, he ran back to his dead pony and started tugging at the headpiece amid sustained enemy fire. “Bullets were flying on top of my head,” Limpy recalled.

From a distance Young Two Moon saw Limpy’s plight, and that mounted Army scouts were rushing toward him, aiming to kill and count coup. Setting out on horseback to rescue his fellow warrior, Young Two Moon reached Limpy, but the crippled boy was unable to jump on the pony’s back, and the two again parted. With the enemy closing in, Limpy hobbled over to one of the smaller sandstone rocks and clambered atop it. Young Two Moon then rode out a second time, and this time from his perch Limpy was able to scramble onto the pony’s back. Riding double, the Cheyennes escaped, Limpy clutching both his weapon and the prized bridle. He soon took charge of a captured horse and set out again with his five companions. Joining another body of Indians, mostly Cheyennes, the six again charged into the fight.

Limpy’s story also had an epilogue set in modern times. In 1934, to mark the 58th anniversary of the Battle of the Rosebud, the Billings chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution unveiled a monument of stone and bronze atop a knoll at the Big Bend of the Rosebud. The marker was one in a wave of memorials orchestrated by the national DAR to mark such historic American sites. Imposing as it was, however, more striking was the presence of four old men—Beaver Heart, Louis Dog, Wheezer Bear and Charles Limpy of the “Limpy’s Rocks” episode in 1876. The four had journeyed from the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation for the unveiling. A fifth old man, Kills Night, was blind and ailing and remained home near Busby, lamenting his inability to attend. All were veterans of the Rosebud battle, acknowledged as the last of the Cheyennes who had fought both there and at the Little Bighorn. Three came dressed in historical garb, and, according to a reporter from The Billings Gazette, all were in a talkative mood. That bright, hot afternoon the four wizened Cheyennes shared their stories of the fight, adding to the rich tapestry of the Rosebud.

Such chroniclers as Thomas Bailey Marquis and John Stands in Timber captured and published similar Northern Cheyenne accounts, further perpetuating the tribal legacy of the place. For those four old men and all the Northern Cheyennes, then as now, languid Rosebud Creek and the surrounding battlefield remain sacred ground, both in physical proximity and in the sanctuary of their collective memory.

Paul Hedren, a retired National Park Service historian and superintendent, drew these stories from his forthcoming book Rosebud, June 17, 1876: Prelude to the Little Big Horn. For further reading see Hedren’s Traveler’s Guide to the Great Sioux War: The Battlefields, Forts and Related Sites of America’s Greatest Indian War.