Last time out we began a discussion of the importance of studying maneuvers. They can tell a historian a lot about the way an army trains, about its policies and procedures, about what it intends to do once war breaks out, of course. They can tell you even deeper things about a “way of war”—longstanding operational patterns that cut across the fighting style of individual generals, across wars, and even across the centuries.

Exhibit A in that contention: the Wehrmacht’s “Great Fall Maneuvers” of 1937. The big story here was the debut of a new formation in the German battle array, the “Panzer Division.” It was built around tanks, but also contained a full array of supporting arms—infantry, artillery, engineers, supply troops—all of which could move at the speed of the tank. It was a new animal, being formed only at the end of 1935, and this was the first big field test. There was a definite aura of excitement, and indeed, the 1937 maneuvers were the largest exercise held in Germany since the end of World War I, attended in person by Hitler, Mussolini and a whole host of foreign observers.

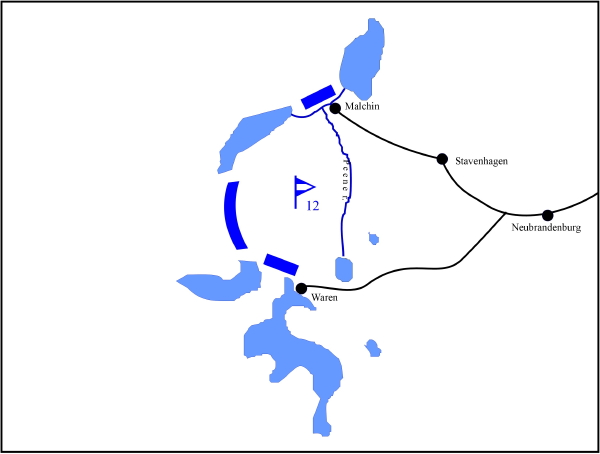

As always in a German maneuver, a “Blue force” faced “Red” in an imaginary theater of war, this one consisting of the rolling hills, lakes, and streams of Mecklenburg, the epicenter of the so-called North German Plain. Blue, in the East, held a bridgehead over the winding Peene river near Lake Malchin (above). Red, to the West, had to attack the bridgehead and had the 3rd Panzer Division in its order of battle for that purpose. Any doubts about the ability of a mechanized formation to mix it up in high tempo operations—and there were doubters, many of them—vanished almost immediately.

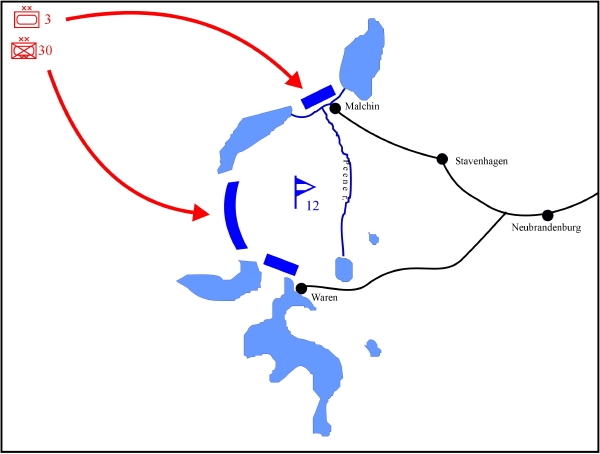

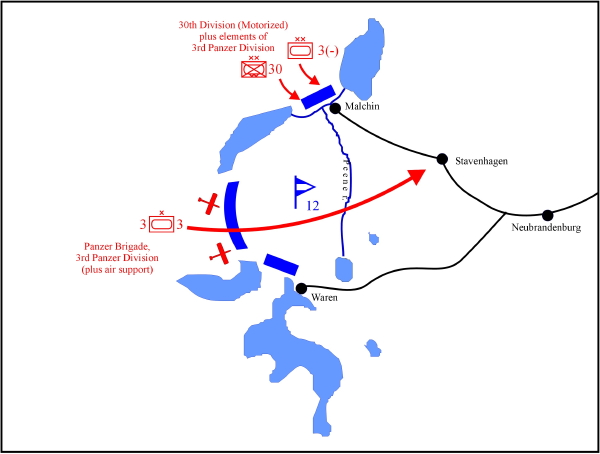

Moving up 100 kilometers from the army reserve to its assault position in a single day (September 19th, above), 3rd Panzer Division launched its assault on September 20th (below). It sent its motorized infantry brigade for-ward to help 30th Infantry Division (also motorized) engage the bridgehead frontally, while swinging its Panzer Brigade around Blue’s extreme left in the South. Working in close liaison with airpower, the panzers broke through the Blue position. Lacking specific orders but seizing an opportunity that suddenly presented itself, the Panzer Brigade then drove on the town of Stavenhagen, reaching it, scattering Blue’s headquarters, and cutting off Blue’s supply route into Malchin.

Having encircled the entire bridgehead, still without pausing, Red now assaulted it concentrically. Blue reinforcements were late in arriving due to a vigorous Red air interdiction effort. As a result, midway through Day 4 of a scheduled seven-day maneuver, Red had smashed its Blue foe.

In the manner of these things, there were debates about whether the umpires were playing fair—specifically, whether they underestimating the effect of defensive antitank fire. In order to sooth ruffled feelings, 3rd Panzer Division was ordered out of the maneuver, which continued as a fairly trite infantry vs. infantry encounter.

Beyond testing the capabilities of the Panzer Division, the maneuver was an almost perfect distillation of the “German way of war”: high tempo, independent decision making and a great deal of risk (in this case rushing 3rd Panzer Division into combat “off the march” and splitting it in two for purposes of the concentric attack. A pretty impressive package, all told: a near picture-perfect image of an army putting its game face on.

Next time? The U.S. Army in Louisiana.

For the latest in military history from World War II’s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.