When Jürgen Oesten, the famed U-boat captain, was asked postwar to reflect upon the career of the U-505, he answered with typical German laconism. “U-505,” he said. “Not what I would call a lucky boat.”

That was an understatement: at a time when unterseeboots were terrorizing the Allies, the U-505 was the cursed child of the Kriegsmarine. Launched in May 1941, its promising first year was cut short when the commander, Axel Löwe, came down with a career-ending case of appendicitis. Under Löwe’s replacement, Peter Zschech, the boat was plagued by mechanical problems.

The U-505 spent 10 months docked at the U-boat pen in Lorient, France, often venturing out to sea only to return a few days later with some glitch or another. Some suspected the submarine was being sabotaged by the Resistance—or by Zschech himself. Pranksters wrote poems mocking “the U-boat that sailed out every morning and was back every evening” and its commander. Though the U-505 was ready to patrol again in October 1943, Zschech was not: he committed suicide the next time the crew went to sea, in the middle of a depth charge attack.

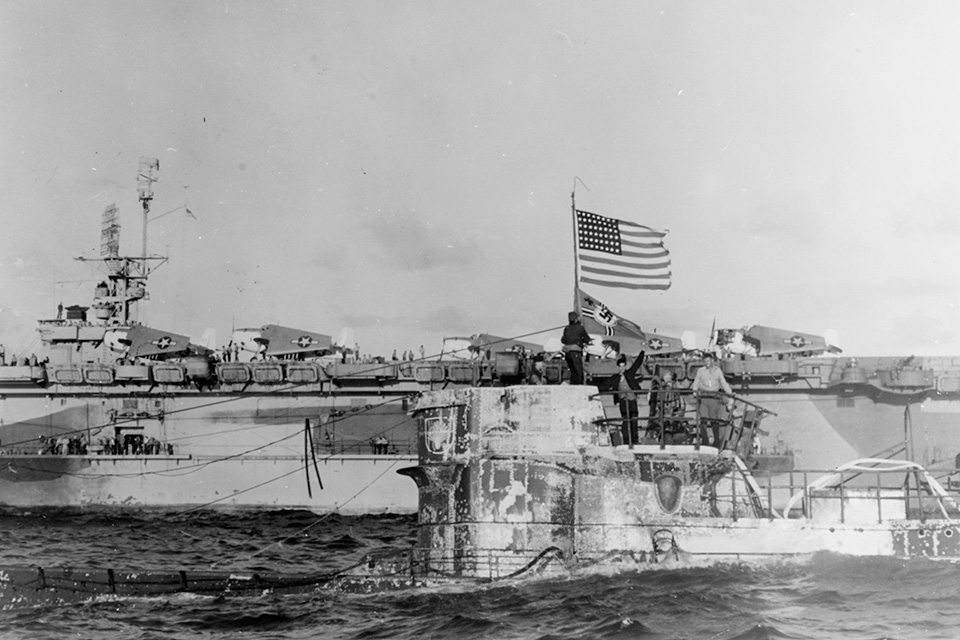

The final blow to the U-505’s reputation came on June 4, 1944, when U.S. Navy Task Group 22.3 intercepted it off the coast of West Africa. Hammering the sub with hedgehog mortars and depth charges, the Americans forced it to the surface.

The U-505’s commander, Harald Lange, ordered his crew to leave the boat, and though they set scuttle charges and opened a sea strainer to flood the U-505 before abandoning it, a nine-man American boarding party managed to secure the sub and seize it. The task group took the Germans prisoner, and the U-505 endured a humiliating tow to Bermuda as the first enemy vessel captured by the U.S. Navy since the War of 1812. Perhaps it was that final ignominy that caused the U-505 to go down in the German collective memory as “the sorriest U-boat in the Atlantic force.”

But the moment the Americans seized the U-505 is exactly when the boat’s luck started to change. The man who masterminded the capture, Capt. Daniel V. Gallery, went after the German submarine with the intention of bringing it back to Allied territory intact. And after the navy had squeezed every German secret from the submarine, made the capture public, and announced its plans to scuttle it, Gallery embarked on an eight-year campaign to repair the damaged U-boat and bring it to his hometown, Chicago, Illinois.

Known for his perseverance and omnipresent sense of humor (“Keep your bowels open & your mouths shut,” reads a memo he wrote to his men after the boat’s capture), Gallery used his military connections and media savvy to raise some $200,000 to bring the boat to Chicago from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by way of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. The journey culminated in a grand ceremony on June 26, 1954, when the U-505 was towed across Lake Michigan—with Gallery aboard.

Thanks largely to his efforts, the U-505 now has a permanent home at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. Recently renovated, it is the only German submarine in the United States, and one of only four World War II–era U-boats in the world on display. More than 23 million people have seen the U-505 since it first arrived in 1954. Today I’ve come to see the beached behemoth for myself.

The museum is in Jackson Park, adjacent to Lake Michigan, in an ornate 19th-century building that must have made a striking contrast to the sleek submarine during the boat’s 50-year stint outside the museum’s walls. Exposure to the harsh Chicago weather took its toll, and in 1997 the curators began to restore the boat and move it to an underground, climate-controlled space. My relief that U-505 is now protected from the elements isn’t purely preservationist: a cold, rain-soaked wind is blowing from the lake, and I’m eager to escape it.

The exhibit begins at a narrow, dramatically lit hallway, with no submarine in sight. Instead, plaques, murals, and film footage provide visitors with a comprehensive history of the war and the U-505’s capture. This is all new; when the exhibit opened in the 1950s, most of its visitors had lived through the war. Now the conflict must be recreated for generations that are two and three times removed.

Lulled by the winding hallway, I turn a corner to find myself face-to-bow with 252 feet of imposing gray and white steel. The U-505 looks every inch the silent killer, and the lightning bolt–shaped victory rune painted on its conning tower does nothing to dispel that impression. I’m reminded of Winston Churchill’s postwar admission that “the only thing that ever really frightened me was the U-boat peril.” In the murky light, it’s easy to imagine the boat submerged in wait, ready to strike a passing convoy.

This single stunning artifact is the centerpiece of an admirable collection of nearly 200 relics from the war. The space around the boat is crammed with them: a sampling of the U-505’s 87 phonograph records (some were found in pieces—apparently not everyone onboard cared for opera), a can of bread dough that was discovered in the bilges in 1994, and the crew’s personal effects. There’s a T5 acoustic torpedo behind a pane of glass, its inner workings laid bare, and the boat’s original aerial-navigation periscope.

One of its two Enigma machines is on display here too, along with codebooks whose covers are weighted with lead (the better to sink when thrown overboard). Visitors can sit in a recreated control room, or fill the ballast tanks of a model sub with air to adjust its buoyancy. And the U-505’s conning tower, bunks, and galley have all been replicated outside the boat. You could spend hours in the exhibit without ever touring the U-505 itself.

But that would be a mistake. Seven years and $35 million were poured into the recent restoration, and you have to see the boat up close to truly appreciate its beauty. The onboard tour is likely the only opportunity you’ll ever have to see an authentic German U-boat the way it was intended to be seen: as state-of-the-art military technology. The gray paint on the hull is fresh and clean; the wood paneling in the officers’ quarters gleams. Every gauge, every dial, every pipe (and there are a lot of them) is in its right place. Even the darkness reveals how meticulous the restoration was: in the electric motor room, with the lights out, the gauges, hatches, and ladders glow faintly. They’re outlined in phosphorescent paint, the same kind the Germans used so that the crew could continue working even in an emergency.

I’m struck by how narrow the sub is inside—and how efficiently the small space was used. A peek into the bunk-lined torpedo room reveals that some crewmembers slept just inches away from the boat’s deadly ammo. Of the two tiny bathrooms, one doubled as food storage, and there was no place for the men to bathe. There were 59 men aboard the U-505 during its final patrol; I’m claustrophobic in my tour group of 12.

Compared to most German subs, though, the U-505 is the luxury sedan of U-boats—a Type IXC. It was designed for long, solitary journeys, not the wolf pack hunts often associated with submarines, and so the interior is a bit roomier than that of the average U-boat. Though the U-505’s record was unremarkable, the Type IX was one of the Kriegsmarine’s most successful models: Type IXs constitute 8 of the 10 most successful U-boats of all time. This submarine was once a ruthless and efficient killing machine—which must have made seizing the U-505 all the more satisfying for the Americans who took it down. That was a turning point: the moment the obscure became known. I can understand why Gallery felt such drive to preserve it; he called the captured U-boat “a unique symbol of victory at sea.” It is his, and Chicago’s, war trophy.

I linger at the end of the exhibit, still spellbound by this powerful weapon and the fantastic voyage that brought it here. I find I’m not the only visitor who’s found it hard to leave. Clearly the boat’s final lucky break was lucky for us as well.

Admission to the U-505 exhibit is included in the Museum of Science and Industry’s $13 entry fee ($9 children; $12 seniors); timed tickets for the onboard tour are an additional $6 per person. Only a limited number of people can tour the sub each day, so buying tour tickets in advance at msichicago.org is recommended.

Where to Eat

Continue the day’s nautical theme by heading to Navy Pier, Chicago’s popular lakefront entertainment complex, to grab a bite and boat-watch as the sun sinks beneath the Chicago skyline. I had a lovely dinner there at Riva, a steak and seafood place, where picture windows offer stellar views of Lake Michigan and downtown Chicago (stefanirestaurants.com/riva).

What Else to See

The Museum of Science and Industry is one of the most popular sites in Chicago, and deservedly so. Air power buffs will enjoy a close look at the Spitfire Mk I and the Ju 87R-2 Tropical Stuka on display in the museum’s transportation gallery; a naval exhibit lets visitors tour an aircraft carrier, climb aboard an F-35C flight simulator, and scan Lake Michigan for enemy vessels through the periscope of the nuclear-powered submarine USS Chicago.