It was Friday, November 22, 1935. Crowds were gathered along the shores of San Francisco Bay to witness an epoch-making event–the first commercial airmail flight across the Pacific to Asia. Although it was a working weekday, a holiday mood prevailed as an estimated 20,000 people made their way to the Pan American Airways operating base at Alameda, where the inauguration ceremonies were about to begin.

On the shore’s edge, near the marine ramp, a raised platform held numerous dignitaries, out to sanctify the occasion with the laudatory prose of their speeches. The chief guest was U.S. Postmaster General James A. Farley, but others were also due to speak, including California Governor Frank Merriam and Pan Am President Juan Trippe. A radio hookup stood ready to broadcast the proceedings to the world.

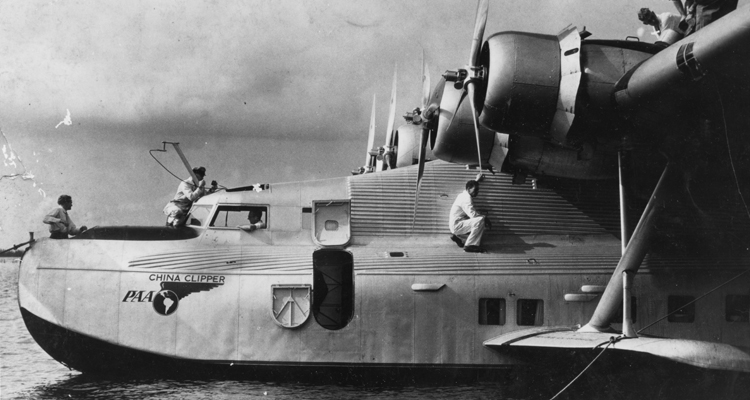

Just offshore, only a few yards from the speaker’s dais, nose and cockpit looming over the speaker’s platform like a giant eavesdropper, floated the China Clipper–Martin M-130 flying boat, one of the most advanced aircraft of its day.

All the press, hoopla and publicity was designed to celebrate Pan Am’s triumph and also lift some of the gloom from a Depression-plagued public. Earlier, Postmaster Farley had made a great show of ‘loading’ the sacks of mail into the plane himself. To underscore the great progress that had been made since the 19th century, a horse-drawn Concord coach rattled up to deposit the final sacks of letters. All told, there were 58 sacks in the cargo, totaling some 110,865 pieces of mail that weighed 1,837 pounds.

After a round of speeches, and the reading of a letter from President Franklin Roosevelt. The China Clipper made its way beyond a protective breakwater and onto the broad bay. Its audience was not confined to Alameda; an estimated 150,000 people watched from San Francisco, the Marin Headlands and other points around the bay.

With veteran pilot Edwin Musick at the controls, China Clipper‘s quartet of engines revved up. When the ‘all clear’ signal was given, China Clipper plowed bay waters into a foam-flecked wake before lifting off at 3:46 p.m. Pacific Standard Time. The giant aircraft made its way toward the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge then under construction. A swarm of smaller planes followed in escort, little knowing a crisis loomed ahead.

Within seconds, Captain Musick realized China Clipper was in danger. The bridge’s roadbed wasn’t yet built, but the suspension cables that linked the towers had wires dangling below them like metal fringe. ‘It had been our intention to fly over the bridge,’ second engineering officer Victor Wright recalled years later, ‘but Musick quickly saw that with the engine cowl flaps open he wouldn’t be able to get up enough speed to clear the wires, so he nosed the Clipper down at the last moment and went under the bridge cables, threading his way through dangling construction wires. We all ducked and held our breath until we were in the clear.’

The crisis averted, China Clipper headed out into the Pacific, its ultimate destination Manila, the Philippines. Gaping crowds marveled, thrilled at the aerial drama they had just witnessed. Later local newspapers played down the incident, declaring the nose dive had been a planned ‘part of the program.’

After island-hopping stops at Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island and Guam, China Clipper successfully completed its inaugural run by landing in Manila, November 29, 1935. The journey had taken 59 hours and 48 minutes flying time, and had traversed 8,210 miles. With this one historic flight, the world had become smaller; the China Clipper took 6 1/2 days to do what would take 21 days in the fastest passenger ship.

China Clipper‘s trans-Pacific flight was the product of one man’s vision, Pan Am President Juan Trippe. This was a man with a mission, and the mission was to blaze a network of international air routes that would gird the glob. But Trippe needed an instrument to put his idea into effect, and that tool was Pan American Airways.

Founded by Trippe in 1927, the company was truly ‘Pan American’ as it extended service throughout Latin America and forged pioneering links between the United States and its neighbors to the south. By 1931, a scant four years after Pan Am’s birth, Trippe’s ambitions already extended beyond the Western Hemisphere.

Blocked by political problems from developing service across the Atlantic to Europe, Trippe turned his attention to the Pacific instead. On June 26, 1931, Trippe and his chief engineer, Andre Priester, issued what amounted to a challenge to the aircraft industry–they wanted a large, long-range seaplane capable of transoceanic flight.

The Glenn L. Martin Company of Baltimore, Md., took up the gauntlet. Determined to succeed, Martin and his engineers huddled and sweat over hundreds of sketches, mulling over everything from wing design to color schemes for passenger cabins. Martin’s proposals were deemed satisfactory, and Pan Am placed an order for three flying boats late in 1932. The result of all this trepidation, inspirations and perspiration was the Martin M-130.

Now that he had airplanes in the works, Trippe’s next step was to find a feasible route across the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific is immense, and the Pan Am president knew that well over 8,000 miles separated the west cost of the United States from China and other potentially lucrative markets.

Trippe realized they had two basic route options: The ‘great circle’ or island-hopping. The great circle route–partly blazed by famed aviator Charles A. Lindbergh in 1931–would run up the west coast of Alaska, arc across the Aleutian chain of islands, and then hop across to the edges of Siberia before dropping down to China and the Philippines.

There were drawbacks to the great circle. Meteorological conditions in the far north could be harsh, and the Aleutians were plagued by thick fogs. But above all, the Soviet government refused to grant landing rights in Siberia.

Trippe decided on a bolder course. He would strike out directly across the Pacific, island-hopping as he went. Among the advantages to this plan was the fact that the United States owned Hawaii, Guam, the Philippines, and other Pacific islands that were ready-made way stations.

In 1934, Trippe caused a commotion among his board of directors by prematurely announcing, ‘We are now ready to fly the Pacific.’ In December of that year, the first China Clipper emerged from the Baltimore factory. Extensive testing proved the soundness of her design, and she was delivered in October 1935.

The China Clipper and her two sister ships were giants by anyone’s definition, measuring 130 feet from wingtip to wingtip and 91 feet from nose to tail. Four Pratt and Whitney 830-hp engines provided the power needed to lift the airplane’s 52,850-pound gross weight, and once they hit their stride, an air-speed of 130 mph could be attained.

The spacious fuselage could accommodate up to 32 passengers, and with the exception of fabric covering for the wing trailing edge, the airplane boasted an all-metal construction. The hull was double-bottomed, and to provide lateral stability on the water, stubby sea wings protruded from under the fuselage, connected to the great main wings by struts. The sea wings were a more efficient substitute for the drag-inducing wingtip floats that kept earlier seaplanes from tipping over on the water.

Meanwhile, Pan Am’s trailblazing Pacific leaps were being planned with infinite care. The first leg of the journey would also be the most daunting: 2,400 miles of open ocean between the California coast and Hawaii. After that, the distances were also great but less formidable: Honolulu to Midway Island, 1,260 miles; Midway to Wake Island, 1,320 miles; Wake to Guam, 1,500 miles; Guam to Manila, 1,600 miles and, finally, Manila to Hong Kong, 600 miles.

Manila was Pan Am’s first air terminus, not the British crown colony of Hong Kong, because His Majesty’s government refused Trippe landing rights. In fact, one of their own carriers, Imperial Airways, had plans to develop the territory, and the British were not about to let an impudent Yankee in.

But Juan Trippe was an old hand at overcoming obstacles. He simply entered into negotiations with the Portuguese for landing rights at nearby Macao. When Lisbon granted these rights in 1936, the British reluctantly allowed Pan Am to use Hong Kong as well.

To achieve its objectives, Pan Am chartered an merchant steamer New Haven and loaded it with 6,000 tons of supplies. Two complete villages, seagoing motor launches, diesel generators, water distillations units, and many other items went into its gaping hold. The passenger roster included 44 airline technicians and a 74-man construction crew.

The New Haven hoisted anchor and left San Francisco on March 27, 1935, bound for Honolulu and points west. The first major landing was at Midway, then New Haven proceeded to Wake Island; Guam was to be prepared separately from the Philippine end of the route.

Once the island bases were well underway, Trippe moved on to the next phase–survey flights. Trippe turned to another flying boat, the Sikorsky S-42, to begin the surveys at once. The S-42 was a graceful craft, the workhorse of Pan Am’s Latin American system, but the airplane had only a 750-mile range, too short for the vast Pacific. Trippe modified an S-42 Sikorsky flying boat, the Pan American Clipper, with added fuel tanks, boosting its range to nearly 3,000 miles.

Survey flights began in April 1935, under the command of chief pilot Edwin Musick. The navigator was Fred Noonan, who was destined to be lost with aviatrix Amelia Earhart in 1937. The surveys, which lasted some five months, were a success and proved Trippe was on the right track. Nothing was left to chance; on one return flight to San Francisco, the crew experimented with flying blind in a hooded cockpit to test the instruments.

By November 1935, Pan American Airways had invested $925,000 in developing a Pacific route, a considerable outlay for the time. But all the effort was rewarded when China Clipper lifted off on the historic first flight. In recognition of its pioneering feats, Pan American was awarded the Collier Trophy in 1936.

By mid-1936, the China Clipper was joined by the two other M-130s, Hawaiian (later Hawaii) Clipper and Philippine Clipper. For all their justly deserved fame, only three Martin M-130s were ever built, perhaps because they were enormously expensive. Each fully equipped Martin cost $417,000 at a time when the largest contemporary land-plane, the Douglas DC-2, rang in at $78,000 apiece.

Flying the U.S. mail was all very well, and the government FAM-14 contract rate of $2 a mile added revenue to Pan Am’s coffers. Still, Trippe wanted to carry passengers almost from day one. He soon got his wish. On October 21, 1936, just under a year since China Clipper‘s groundbreaking jaunt, Hawaiian Clipper started the world’s first transoceanic scheduled passenger flight across the Pacific to Manila. There were only seven passengers on this maiden run, but Trippe was vindicated. In the spring of 1937, regular mail-and-passenger service began to Hong Kong and Macao.

Through published memoirs and reams of Pan American Airways publicity material, it is easy to reconstruct a ‘typical’ Pacific crossing in the late 1930s. For our purposes, we will assume the year is 1939, and the aircraft is the China Clipper herself.

To begin with, your typical passenger–let us say a businessman– would arrive in San Francisco. Pam Am pamphlets dwell on luxury, and our businessman would have to be well-heeled as well as adventurous. The one-way fare from San Francisco to Manila was $799, roughly $10,000 in today’s money and twice the supersonic Concorde’s tariff. The fare to Hong Kong was a whopping $950 one-way, and certainly out of the reach of most Depression-era pocketbooks.

Passengers would be driven across the newly completed Bay Bridge, or would perhaps take a ferry, to reach the Alameda Airport. Once at the airport, travelers would check their luggage, but other routines were a far cry from today’s computerized departures. Pan Am’s pamphlets warn that 55 pounds is the baggage limit, with no exceptions and the passengers will also be weighed. This was crucial, particularly on the San Francisco-Hawaii leg, because added pounds gulped precious fuel.

Not surprisingly, a nautical flavor clung to the Clippers. At the sound of first bell, the captain and his seven-man crew would board the M-130 as she lay beside a floating pier; they would be dressed in double-breasted dark-blue tunics and white caps, all suggestive of the Navy.

Actual takeoffs would be at 3 p.m., and as the China Clipper winged across the Pacific, it would encounter an almost purple twilight. Taking a Clipper, rhapsodized the airline, is to’sail beyond the sunset and the paths of Western stars in a modern way that would have thrilled Ulysses.’

The first lap of the journey would take our businessman to Honolulu, Hawaii, some 2,400 from the California mainland. This was the longest stretch, some 18 hours of largely overnight flight.

Passengers moved about the cabin freely, their every wish catered to by white-uniformed attendants. Publicity photos showed men and women playing cards, backgammon and checkers while seated in comfy wicker chairs. Oddly, nothing seems to be bolted down; seat belts are nowhere to be seen.

Before retiring to their sleeping berths that first evening, voyagers would assemble at the dining lounge for a meal complete with fine china, silverware and white tablecloths. The next morning China Clipper would land in Hawaii, but before they knew it passengers would be off to the next stop, Midway Island, some 1,320 miles due west.

Midway is actually two knobs of land, Sand Island and Eastern Island, both surrounded by a coral reef Pan American built while based there, including a hotel, powerhouse, and refrigeration plant. If on schedule, the Clippers would spend an afternoon and one night at Midway–ample time, says the literature, to sample the island’s great golf course.

The China Clipper would next head to Wake Island, crossing the International Date Line en route and losing a day. Barely 3 1/2 miles long and one mile wide, Wake is a tiny arc of sand that noses above the ocean’s surface. Surrounded by a coral barrier reef, Wake’s chain of three islets encloses a shallow lagoon noted for its sky-blue color and teeming fish life.

For all its picturesque qualities, Wake was the hardest for Pan Am to colonize and develop. Before service was started, coral heads had to be blasted out of the lagoon to make it safe for landings. The job took five months and consumed five tons of dynamite. Since the sand would not support vegetation, several tons of topsoil had to be imported from Guam. But most of all, Wake hand no fresh water, and wells produced only salt water. Distillation plants had to be shipped in.

If that was not bad enough, Wake was swarming with rats–descendants of rodents left behind by passing ships. Pan Am personnel fought a seesaw battle with the pests; one China Clipper flight had air rifles to use against them.

If Pan Am publicity is to be credited, passengers stopping at Wake could beachcomb for colorful Japanese fishing floats–an innocent remark, but ominous in light of future history. Japan had a mandated island in the Pacific, and the militarists in Tokyo were suspicious about Pan Am’s string of island bases, feeling that they could easily be converted for military use. Japanese newspapers printed unofficial protests that deemed the Pan Am installations an ‘unfriendly act.’ The Japanese fishing floats were symbols of an aggressive presence, one that might do anything to further its aims.

Once Wake was left behind–by this time, it is the fourth day–our businessman’s destination was Guam. Guam was lush and green, and had a friendly Polynesian native population under the U.S. flag. Finally, the China Clipper would proceed to Manila, capital of the Philippines–a U.S. possession at the time, America’s outpost in the Far East.

The Pan Am Philippine base was at Cavite, on Manila Bay. Many years after the Clipper era, Pan Am mechanic Rafael Francisco recalled that maintaining a Martin M-0130 on the water had unique problems: ‘When a wrench or hammer dropped into the water, I had to strip to my trunks to dive after the object.’

Manila would be the end of the line for may passengers, about six days after leaving the United States–a long time, but again, far faster than the 21 days it took the fastest steamship. Others, though, would continue on to Hong Kong, about five hours and 600 miles from the Philippine capital.

The Pan Am literature describes China with a blend of wide-eyed naiveté, Kiplingesque colonialism and unconscious racism. The airline waxes poetic about the ‘unchanging oriental’ in a fabulous land, and evokes Marco Polo. But nary a word is spoken about the bloody Sino-Japanese war that was raging at the time.

Once the San Francisco-Hong Kong route was firmly established, Trippe made plans to extend service from Hawaii to Auckland, New Zealand. Once in New Zealand, passengers could make connections to go to Australia. It naturally fell to the chief pilot, Edwin Musick, to begin survey flights for the venture, but his S-42, the Samoan Clipper, was blown up with the loss of all hands near Pago Pago. It was a major tragedy, but eventually the Hawaii-New Zealand service was established in 1940.

Of the three-ship fleet of Martin M-130s, the China Clipper was the most famous, in large part due to its notable 1935 first flight. Even Hollywood had gotten into the act; a fictionalized retelling of its Pacific conquest appeared in a 1936 movies called China Clipper; starring Humphrey Bogart and Pat O’Brien.

China Clipper carried all sorts of cargo during its illustrious career. The giant flying boat flew orchids and other tropical plants to San Francisco’s 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island. Some flights were literally milk runs; Pan Am workers on Wake and Midway thirsted for milk, so the China Clipper would bring in a large supply packed in ice.

All sorts of people took the China Clipper; ranging from the ordinary businessman to the world-famous. Major General Clair Chennault flew in it three times while he was organizing his famous Flying Tigers group against the Japanese in China. Soviet Ambassador Maxim Litvinoff also took the China Clipper, and so did Japanese diplomat Saburo Kurusu. Kurusu was probably the most ‘infamous’ passenger, at least to World War II Americans, for he was one of those who entered into last-minute negotiations with Washington in November 1941, shortly before war broke out.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, brought the golden age of Pacific flying boats to an abrupt end. Pearl Harbor took Pan American Airways by surprise; it was still operating regularly scheduled peacetime runs at the time of the attack. Wake Island was marked for special Japanese attention, and a devastating air raid blasted its facilities to shreds.

It just so happened that the Philippine Clipper was moored at Wake during the attack, and was brutally machine-gunned, although not destroyed. Peppered with 97 bullets, the gallant M-130 managed to evacuate Pan Am personnel from the stricken island. Unfortunately, nine of Pan Am’s complement of 66 employees were killed in the raid.

Midway also suffered air attacks, as did Hong Kong. An S-42, the Hong Kong Clipper, was burned to the waterline as it lay moored in the British crown colony. Pan Am’s growing trans-Pacific branches were pruned to a stump in December, 1941–but that’stump’ was the vital California-Hawaii run. Pan Am placed itself at the disposal of the U.S. government, and did sterling service throughout the war.

Fate was not so kind to the Martin 130s. The Hawaii Clipper was lost without a trace east of the Philippines in 1938, with nine crew members and six passengers aboard. The Philippine Clipper crashed into a northern California mountain in 1943. But the most famous Clipper of all, the China Clipper, was transferred to the Caribbean before disaster stuck it, too. On the evening of January 8, 1945, China Clipper stuck an obstacle in the water at Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. The double hull ruptured and the airplane sank. Of the 30 people aboard, 23 were killed, including nine members of the 12-man crew.

Yet nothing could erase the Martin M-130’s achievement, or its place in aviation history. The Pacific flying boat era lasted less than a decade, but the aircraft blazed trails for others to follow.

This article was written by Eric Niderost and originally published in the March 2000 issue of Aviation History.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!