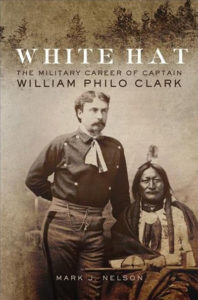

Among the unsung figures of the Indian wars era, William Philo Clark played a pivotal role in the arrest and subsequent death of Lakota war leader Crazy Horse. Earlier the lieutenant had served under Brig. Gen. George Crook as a member of the 1876 Horsemeat (or Starvation) March, which ended with the September 9 and 10 Battle of Slim Buttes and the November 25 attack against Northern Cheyennes known as the Dull Knife Fight. Clark—whom the Lakotas called “White Hat,” for the color of his felt hat—was among the first military men to survey the Little Bighorn Battlefield in the years after that fight. Author Mark Nelson began researching Clark decades ago, perpetually on the lookout for a journal the officer was known to have kept. While Nelson has not found the original diary, he did uncover other interesting documents, which he used to write White Hat: The Military Career of Captain William Philo Clark, which received a 2019 Spur Award for best biography from the Wild West History Association.

Why didn’t Clark advance more rapidly in rank?

Advancement in the frontier army was notoriously slow during the Indians wars period. All officers, including Clark, were hindered by the system at the time. Although his advancement in rank was not rapid, it should be noted he held some highly esteemed positions in the Army, first as adjutant of the 2nd Cavalry and later serving on General Phil Sheridan’s staff.

What was Clark’s role in Crazy Horse’s surrender?

In the months prior to Crazy Horse’s surrender, Clark gathered intelligence on the Oglala Lakota leader’s whereabouts and intentions. He also sent out a small number of Indian couriers to induce Crazy Horse to surrender. Finally, on May 6, 1877, Clark and a detachment of Indian scouts met Crazy Horse about 5 miles west of Red Cloud Agency and held a council with him and some of his headmen. Following the council Clark, Red Cloud and some of the agency headmen led the entire procession back to the agency. After leading Crazy Horse and his people to their designated camping area, the band surrendered its ponies to Red Cloud and Clark’s scouts. The warriors were then instructed to turn over all of their firearms to Clark. When the weapons had been gathered, Clark was not convinced everything had been turned over, and so he, with the assistance of two interpreters and a few of his scouts, conducted a thorough search of each lodge. An additional 41 weapons were seized. The entire process took place in a surprisingly calm atmosphere, with Clark’s cool deportment being credited for that fact.

Clark went so far as to arrange a marriage between Crazy Horse and a mixed-blood girl named Helen ‘Nellie’ Larrabee, in an attempt to mellow Crazy Horse’s attitude toward whites

What about his dealings with Crazy Horse during that summer?

Clark spent much of the summer doing everything he could to befriend the Oglala leader and gain his trust. Clark himself would describe it as “working” Crazy Horse in an effort to sway his thinking concerning the future of his people. Clark was convinced assimilation into the dominant culture was critical to the survival of the Indians. He thought he could convince Crazy Horse and other prominent Indian leaders of this, so they would in turn convince their followers. Clark enlisted Crazy Horse into the Indian scouts and even made him a first sergeant in command of his own company of scouts. He even went so far as to arrange a marriage between Crazy Horse and a mixed-blood girl named Helen “Nellie” Larrabee, in an attempt to mellow Crazy Horse’s attitude toward whites, but the union proved calamitous to Clark’s intentions.

How did Crazy Horse respond?

Crazy Horse appears to have tolerated Clark but manipulated the relationship in order to maintain some degree of power over the northern faction of Indians at the Red Cloud Agency and exercise his own will. Clark’s favoritism and appeasement of Crazy Horse had a negative effect, however, as it fueled jealousy and resentment among Red Cloud and his faction of agency Lakotas. Once Crazy Horse lost Clark’s favor, the Red Cloud faction then manipulated Clark, too, eventually leading to Crazy Horse’s arrest and subsequent death.

What drove them apart?

On Aug. 18, 1877, Clark’s patience and confidence in Crazy Horse finally came to an end when the Lakota leader flatly refused to go to Washington, D.C., as a member of a delegation and also informed Clark who he thought should make the trip. It became clear to Clark he could not win over Crazy Horse to his way of thinking, despite his attempts at friendship and gentle persuasion.

Did the two men share a friendship?

Crazy Horse seemed to tolerate Clark’s friendly overtures and took advantage of the situation when he could, but to what degree he reciprocated true friendship is unknown.

How did misinterpretation of Indian language effect Crazy Horse in those days leading up to his final ride to Camp Robinson?

Much attention has been given to Frank Grouard’s mistranslation of what Touch the Clouds actually said at a council held at the end of August. The Miniconjou leader had stated the northern Indians would go north and help the military fight the Nez Perces. Grouard mistranslated that statement, telling Clark that Touch the Clouds had said the northern Indians would go north and fight the whites. It is interesting to note that after the blunder Clark did not ask for further information about the statement or attempt to clarify through the use of sign language. Instead, he focused his attention specifically on Crazy Horse and his intentions. It was the subsequent heated conversation with Crazy Horse that alarmed Clark the most, for in Clark’s mind Crazy Horse’s insistence to take his people north was the same as a declaration of war. Grouard’s mistranslation simply gave Clark justification to inform military authorities the northern Indians wanted war.

Did that misinterpretation have any lasting impact on Clark?

Clark was very critical of interpreters and blamed their ineptitude in general as being a great source for the misunderstandings between the two races. He apparently learned the sign language rapidly, and his opinion of interpreters may possibly have had some impact on his keen interest in sign language, but that is only conjecture, as it is unknown at what point in his career that he formulated his opinion about interpreters.

Crazy Horse seemed to tolerate Clark’s friendly overtures and took advantage of the situation when he could, but to what degree he reciprocated true friendship is unknown

Did Clark regret his role in Crazy Horse’s death?

Clark initially felt deep remorse and regret Crazy Horse had been killed as a result of his arrest. It is clear Clark simply wanted Crazy Horse removed from the area and even selected a small number of Lakotas to go with Crazy Horse after his arrest, so they could report back to their people the Oglala leader had not been harmed. His remorse did not last long, however, and he soon justified the killing based on the circumstances at the time Crazy Horse was stabbed.

What about Clark’s visits to the Little Bighorn battlefield?

Clark first visited the site in June 1878 and made a second visit in August of the same year. Armed with a vast amount of knowledge gathered from Indian participants of the fight, during his first trip Clark most probably scoured the field in an attempt to more fully understand what had been shared with him. During his second visit to the battlefield Clark was assigned the unenviable task of assisting the Sturgis family in locating the remains of Second Lieutenant James G. Sturgis. There is little doubt Clark also used the occasion to further investigate the battlefield. Clark’s final visit to the site occurred in August 1880. While there he and his men were tasked with making measurements of some of the most controversial parts of the battlefield. Ironically, Clark’s narrative of the battle was committed to paper in the fall of 1877 before he ever visited the site. In September of that year, under verbal orders from Crook, he wrote a report on the Sioux war based on secondhand information he had collected from its Indian participants. That report was accompanied with a map of the battlefield, drawn on the floor of Clark’s quarters by an Indian participant of the fight and later traced by Clark.

What of the two maps made of the Little Bighorn battlefield?

The maps were acquired by Clark during his field work for The Indian Sign Language. They were not necessarily battlefield maps. The first map of “Indian country” was drawn by Sitting Bull’s nephew, One Bull, and another Hunkpapa. One of the most significant aspects of this map is that is showed the trail used by the Indians after their fight with Custer. The other was drawn by the Rev. John P. Williamson, verified by Sitting Bull and of particular importance. It included a narrative of Sitting Bull’s movements after the Custer fight. I have never viewed the originals, and I have no idea where they are or if they even still exist.

Why has Clark been largely overlooked?

Historians have focused most of their attention on the major officers of the time, men such as George Custer, Crook, Nelson Miles and Sheridan, but much less attention has been devoted to junior officers, with a small number of exceptions. During my research I did find a notation that a historian in the 1940s was going through the records of the National Archives with the intention of writing a biography on Clark, but it clearly never came to fruition.

What evidence supports your belief Clark kept a diary?

From reading his book The Indian Sign Language, it is clear he maintained a diary. Also, in one of Clark’s obituaries a quote was printed from his diary, dating from his entry into the U.S. Military Academy. The last known location for the diary was Deer River, N.Y., near the time of Clark’s funeral, in late September 1884.

As you did not locate the diary, what other primary sources did you use?

I relied most heavily on the Records of the Adjutant General’s Office and Records of United States Army Continental Commands. These include letters received, post returns, regimental returns, ACP files, orders and a variety of other material.

What are you working on now?

I’m in the research phase on a biography of James Irwin, the agent at the Red Cloud Agency at the time of Crazy Horse’s death. WW