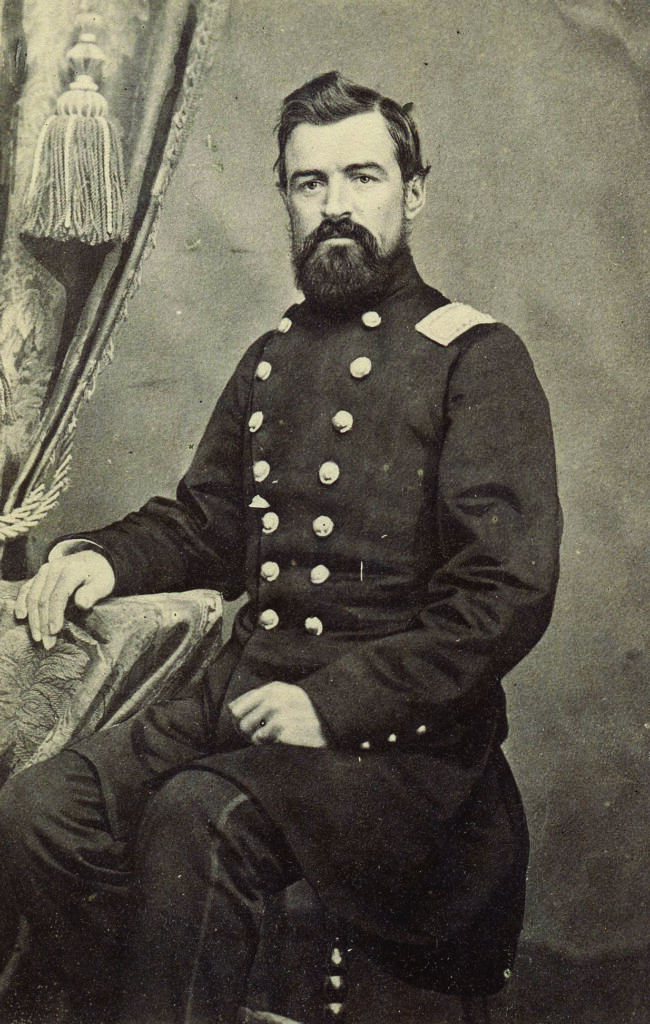

Musing on the Vicksburg Campaign two decades after it occurred, Ulysses S. Grant singled out two subordinates as the best “division commanders as could be found in or out of the army.” These two officers were John A. Logan and Marcellus M. Crocker. Grant further affirmed that the men were “fitted to command independent armies.” Logan’s status continued to rise after Vicksburg, and he eventually did reach army command. Crocker’s career, on the contrary, abruptly ended due to disease, an enemy that scoffed at bullets and bayonets.

Marcellus Monroe Crocker was born in Franklin, Ind., on February 6, 1830. His first name was derived from Latin, and it translated to hammer—a fitting choice for his future exploits on the battlefield. In 1840, 10-year-old Marcellus moved to Illinois with his family, where he remained for five years before relocating to Jefferson County, Iowa. Through the efforts of Representative Shepherd Leffler and Senator Augustus Caesar Dodge, Crocker secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in July 1847 at the age of 17.

Crocker was getting along well in his studies, but two years into his schooling, his father’s sudden death prompted his resignation. His widowed mother was destitute. Crocker packed his bags and returned home to support her, his three sisters, and two brothers. Despite his premature departure from West Point, he never lost his love for military life.

A law career seemed the most appropriate for the ex-cadet. He studied for a short period in Cyrus Olney’s Fairfield office, and after two years of fervent study, Crocker was admitted to the bar and began to practice on his own in Lancaster. He married in 1851, but his 22-year-old bride would die two years later. He then married Charlotte D. O’Neil.

In the spring of 1855, Crocker removed to Des Moines. In 1857, Crocker, Phineas M. Casady, and Jefferson S. Polk established the law firm of Casady, Crocker & Polk. Crocker earned a solid reputation as a criminal lawyer and as an elegant orator. His oratory skills served him well when managing and inspiring green volunteers during the impending war.

A member of the Democratic Party, Crocker fiercely opposed Lincoln’s 1860 Republican candidacy for president. But the outbreak of war caused him to radically shift his opinion and provide unwavering support for the Union cause. At a hastily assembled community meeting in the spring of 1861, Crocker made a short speech that delivered “burning words of patriotism” in support of invading the south and crushing the rebellion.

At a meeting held the next morning, the charismatic attorney gave another rousing speech that called for volunteers to revenge the outrage that transpired at Fort Sumter. “We have not called this meeting for speech-making,” Crocker uttered to his audience. “We are now here for business. The American flag has been insulted, has been fired upon by our own people, but, by the Eternal, it must be maintained!” Eager Iowans offered to serve under the passionate lawyer, captivated by his fiery brown eyes and his enthusiasm to the cause.

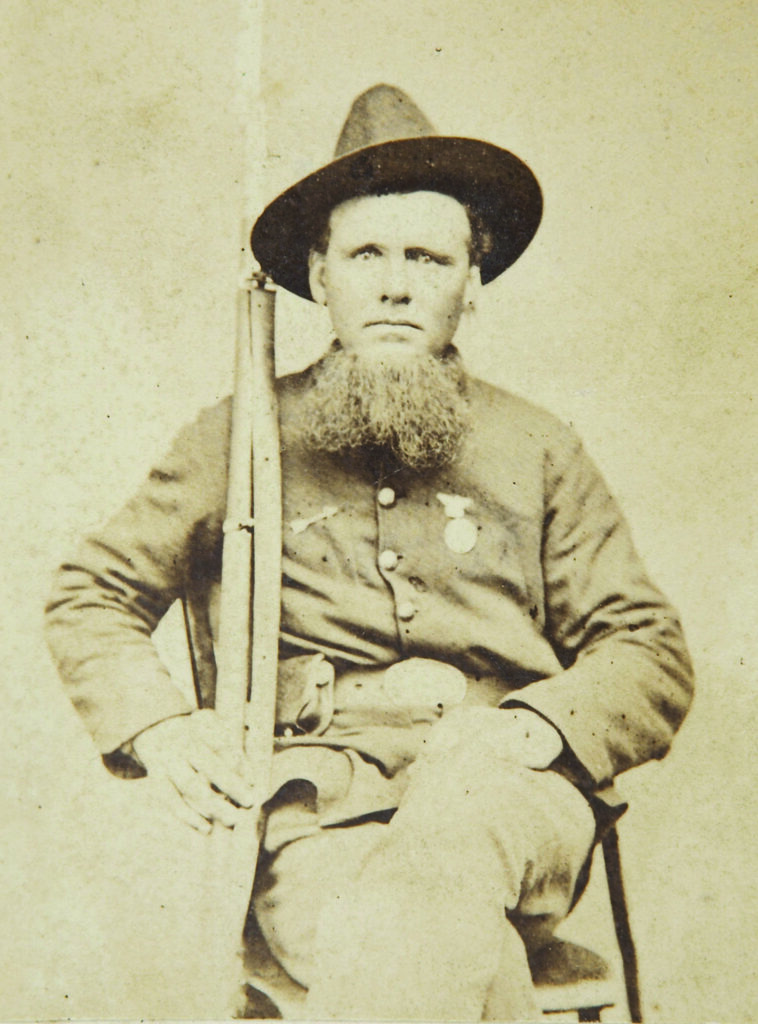

Crocker was elected as a captain in the 2nd Iowa Infantry, and quickly rose in rank to colonel of the 13th Iowa Infantry within seven months. The men under his command recognized him as a pragmatic leader, a savage swearer when provoked, fearless in battle, and a brutish disciplinarian. Captain Cornelius Cadle considered his application of discipline “severe but just.” Crocker made no distinction between officers and the men when it came to enforcing punishment for infractions. Instead, he trusted “that the efficiency, safety and comfort of his men were only secured by their close observance of the duties of a soldier.” Most of the Iowa volunteers were “loud grumblers” because of Crocker’s methods, but their opinions of him quickly shifted when they experienced their first taste of the chaos of battle.

That rude awakening came shortly after Crocker and the 13th Iowa joined Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., in March 1862. Crocker’s regiment, along with the 8th and 18th Illinois, the 11th Iowa, and Battery D, 2nd Illinois Artillery, were part of the 1st Brigade commanded by Colonel Abraham M. Hare of Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand’s 1st Division of the Army of the Tennessee. About dawn on April 6, 1862, General Albert S. Johnston’s Confederate troops smashed into the surprised Union troops in their camps.

Hare’s brigade was almost dead center in the Union line, and though it fought hard, it was driven back before the Rebel onslaught. Hare fell seriously wounded, and Crocker assertively took charge of his green regiments. He recalled his Midwesterners “retired to position in front of the campground of the Fourteenth Iowa Volunteers, and for the rest of the day and until the enemy was repulsed they maintained that position under constant and galling fire from the enemy’s artillery.” The Iowans fought for 10 hours, suffering the loss of two of the regiment’s top senior officers, Lt. Col. Milton Price and Major John Shane, and dozens of men.

But more fighting lay ahead of them. On the morning of the 7th, the 1st Division, commanded then by Colonel James Tuttle of the 2nd Iowa, surged forward as part of Grant’s sweeping counterattack. Crocker’s battered brigade was held in reserve, but two of his regiments got involved in the fight. As the colonel remembered: “The Eighteenth and Eighth Illinois Regiments were ordered to charge upon and take a battery of two guns that had been greatly annoying and damaging our forces. They advanced at a charge bayonets, took the guns, killing nearly all the horses and men, and brought the guns off the field.”

As the fight dwindled down, Crocker was ordered to take his regiments back to their camp, where they arrived about 8 p.m. Crocker’s brigade suffered 577 casualties, including 92 killed, mostly on the battle’s first day. The 13th alone incurred 162 casualties.

Crocker received acclaim for his skillful battlefield command. Colonel Hare, recovering from severe wounds to his hand and arm, praised Crocker’s performance in his post-battle report:

To Colonel M.M. Crocker, of the 13th Iowa, I wish to call special attention. The coolness and bravery displayed by him on the field of battle during the entire action of the 6th: the skill with which he managed his men, and the example of daring and disregard of danger by which he inspired them to do their duty, and stand by their colors, show him to be possessed of the highest qualities of a commander, and entitle him to speedy promotion.

Behind his bravado, Crocker was just happy to have survived. He wrote home to his wife Charlotte reassuring her of his safety a day after the clash:

The great battle is over, and I am untouched, and in good health and spirits. I am very busy, and everything is in great confusion. I have only time to assure you of my safety. God bless you! You don’t know how often I thought of you and the children during the battle.

Colonel Hare resigned due to the effects of his Shiloh wounds, and after a reorganization following Shiloh, Crocker took command of a brigade composed of the 11th, 13th, 15th, and 16th Iowa Infantry. “Crocker’s Greyhounds,” as the units became known, fought in the fall of 1862 at the Battles of Iuka and Second Corinth in northern Mississippi. Crocker’s star continued to rise, and with the backing of his good friend Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, he received a well-deserved promotion to brigadier general in November 1862. The men of his old regiment, the 13th Iowa, presented him with a handsome gold-plated sword as a token of their respect.

Crocker’s leadership skills, however, were powerless against the ravages of tuberculosis. He had suffered from the disease since 1861, but remained in the field despite its miserable symptoms and regularly slept sitting upright in a camp chair at his tent entrance, hoping that exposure to the fresh air would help him breathe. Franc B. Wilkie, a war correspondent of the Chicago Times, described seeing the pale and emaciated general. Wilkie described him as a “very handsome man, something of the style of [Brig. Gen.] John A. Rawlins.” The correspondent noted the “clearness of complexion and the large blazing eyes often characteristic of sufferers from the diabolical disease.”

Crocker refused to go on sick leave. Grant took notice of this endurance and dedication, admiring that Crocker always remained ready for a fight, “as long as he could keep his feet.” Only Charlotte knew the full extent of his suffering. In one letter to his wife, he revealed that “he would have chosen death as sweet relief from his pain, but for leaving his family.”

On May 2, 1863, Crocker received command of Brig. Gen. Isaac F. Quinby’s 7th Division of the 17th Corps. Quinby was wracked by his own illness. When he departed the Greyhounds, Sergeant Alexander G. Downing of the 11th Iowa noted in his diary that “The boys are all sorry to see him [Crocker] leave.”

General Crocker ably led the 7th Division, which consisted of three infantry brigades and an artillery brigade, during the early phases of Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. His division smashed the Confederate works at Jackson, Miss., successfully capturing the city. “It was a most magnificent charge across that open field; in the face of deadly fire our men never wavered, keeping perfect alignment,” Wilkie observed. “Crocker rode on the right of the line, keeping even with it during the charge and going over the works with his men.”

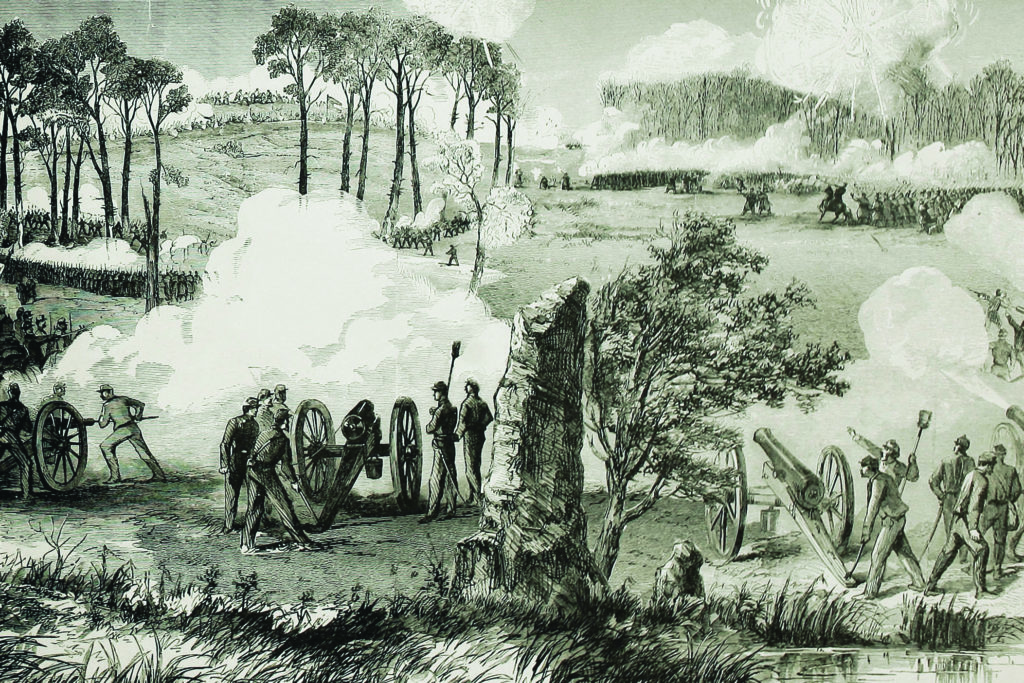

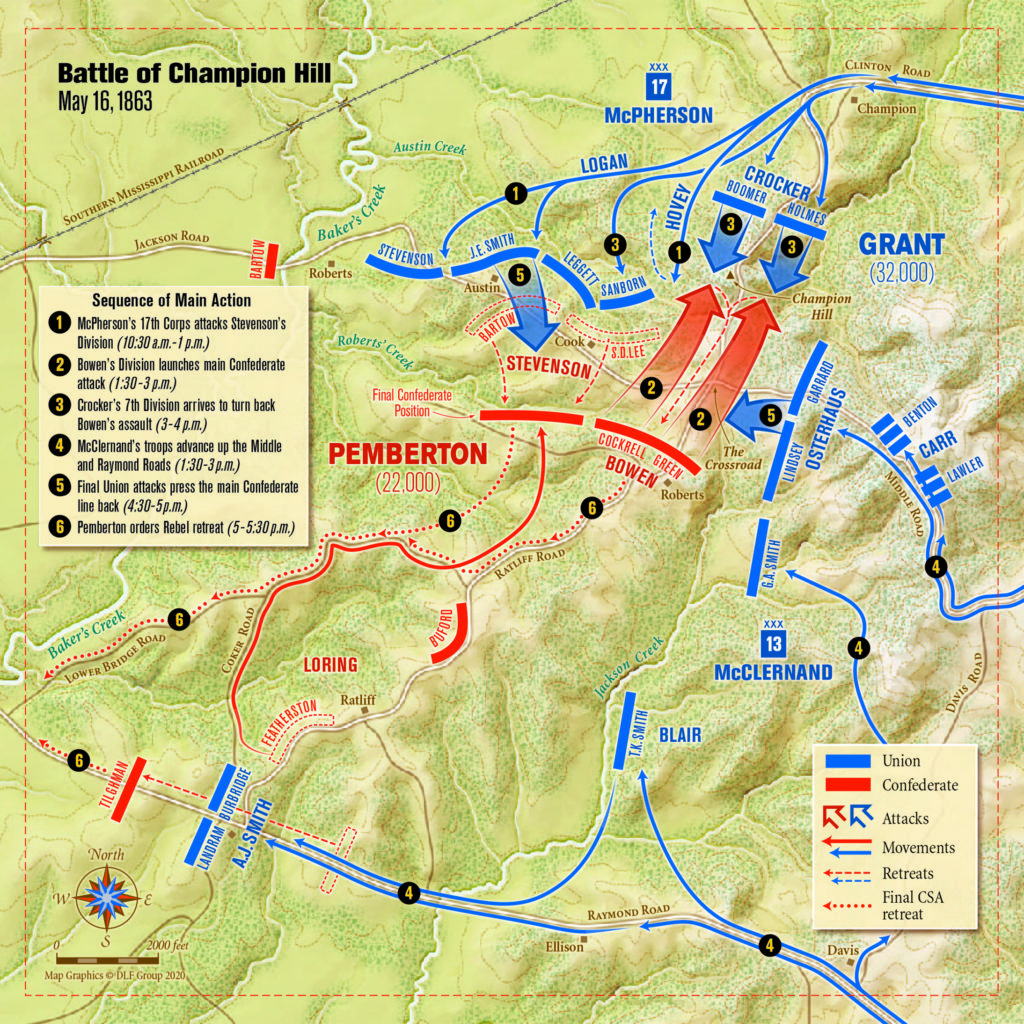

At Champion Hill on May 16, Crocker’s division played a key role and shifted the momentum of the battle. During the opening stage of the fight, Crocker wrote that his brigade commanded by Colonel George Boomer, “by the most desperate fighting, and with wonderful courage and obstinacy,” held fast despite “the continued and furious assaults of the enraged and baffled enemy….”

Boomer’s position became critical, however, when his men ran low on ammunition. At this critical moment, Crocker skillfully fed other regiments of his division into the fight. “They charged the enemy with a shout,” recalled Crocker, and the Confederates “broke and fled in the greatest confusion, leaving in our possession the regimental flag of the Thirty-first Alabama, taken by the Seventeenth Iowa, and two guns of his battery. This ended the fight.”

Fellow Brig. Gen. Manning F. Force described Crocker’s charge as an “irresistible onset” that punched back the Confederate right. The victory forced Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton to retreat into the lines at Vicksburg, where he would be bottled up by Grant’s forces.

Quinby returned to command the division during the fight at Champion Hill, but Crocker kept his command until the battle ended. Major General James B. McPherson, 17th Corps commander, expressed his appreciation for and admired [Crocker’s] his “soldierly qualities,” “efficiency in command,” “gallant heroism on the field,” and lastly, his “daring intrepity.” Grant nominated Crocker as the chief of staff to McPherson until a new assignment opened up. But tuberculosis reared its head once again when Crocker requested from McPherson to go on medical leave in St. Louis for surgery on his throat, which was subsequently granted.

In June 1863, Crocker returned to his hometown of Des Moines following the operation. During the Republican State Convention, participants nominated Crocker as a candidate for governor of Iowa. He refused, kindly asking his name to be removed from the ballot. He humbly declared, “If a soldier is worth anything he cannot be spared from the field; if he is worthless, he will not make a good Governor.”

Crocker returned to Vicksburg on July 21, 1863, finding the city “warm, dusty, and generally as disagreeable as possible,” an environment that tortured his throat and lungs. Grant, though, assigned Crocker to Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord’s 13th Corps to take command of Brig. Gen. Jacob G. Lauman’s 4th Division. Lauman had been relieved of command, according to Crocker, for “blundering like an old ass” into a line of Confederate entrenchments. Grant told Ord he could “place the fullest confidence” in the “brave, competent, and experienced” Crocker.

In August 1863, Crocker’s division was transferred to McPherson’s 17th Corps and dispatched to northeastern Louisiana, where it played a role in Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 1864 Meridian Expedition. Soon after the campaign, Crocker’s health rapidly declined. “I stayed longer than I ought, so that I came very near dying,” Crocker confessed in a solemn letter to his friend General Dodge. He reluctantly relinquished command of his division upon reaching Decatur, Ala., in May 1864.

Crocker submitted his resignation the following month. Halleck telegraphed Grant to ask about Crocker’s previous background while under his command and his capacity to handle an independent “frontier command.” Grant’s reply to Halleck on June 24, 1864, revealed his conviction in Crocker. Grant declared, “Crocker and [Maj. Gen. Phil] Sheridan, I think, were the best Division Commanders I have known.” “Either of them are qualified for any command.” Grant concluded by urging Halleck to dissuade Crocker from resigning.

Crocker agreed to revoke his resignation under the guarantee that he could receive a command in a dry environment that would help to restore his health. Halleck had the Department of New Mexico in mind, and ordered him to report Santa Fe. Although accepting this new assignment without question, Crocker was not, in his own words, “particular about it.” It would be a virtual exile from the major theaters of war. Likewise, he would be isolated from most of “his old comrades.”

Still, the dutiful general made the trek from Leavenworth, Kan., to Santa Fe, arriving in September 1864. He continued to Fort Sumner, where he took command and was tasked with the “care and supervision of 8,000 captive Indians” on the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

Crocker grew restless at this assignment and wrote Grant, pleading to return to active command. Grant immediately telegraphed Halleck on December 28, 1864, requesting Crocker’s reassignment to a command where his talents could be best used. “I have never seen but three or four Division commanders his equal and we want his services,” Grant declared, requesting Halleck to have Crocker report to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland at Nashville, Tenn. Assistant Adjutant General Edward Davis Townsend dispatched the official order for Crocker to return east on New Year’s Eve 1864.

As Grant waited for word of Crocker’s arrival to Nashville, he found another assignment for him. He intended to suspend Maj. Gen. George Crook—captured by guerrillas in February 1865—and replace him with Crocker in command of the Department of West Virginia. Grant wired to Halleck, “If Crocker can be reached he will make a fine Officer to take Crook’s place.”

Grant became irked when the change in command was delayed and rattled off a message to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a fellow advocate for Crocker, toward the end of February. “I asked Gen. Halleck some time since to order Crocker from New Mexico,” Grant declared. “If he is within reach I scarcely know his equal to take Crook’s place.” Grant wired Stanton a second time at the beginning of March. “It will be necessary to have a good man in Command in West Va.,” he noted. “I recommended Crocker for the place but I believe he has not been ordered in from New Mexico. I wanted that done last Fall [Winter] and supposed until a few days since that he had been ordered in.” He sent one last telegraph to Halleck on March 2, 1865, bluntly asking, “Has General Crocker been ordered in from New Mexico? If he has not please order him in at once. He would be invaluable in command of West Virginia. An active traveling general is wanted who would visit all his posts in the department.”

Both Halleck and Stanton reassured Grant on separate occasions that Crocker had been “ordered in some time ago.” Thomas had been ordered to dispatch Crocker upon his arrival, but no one knew his whereabouts. It turned out his illness had returned, and Crocker finally turned up at General Dodge’s headquarters in St. Louis on April 22, 1865. Dodge telegraphed Maj. Gen. John Rawlins of Grant’s staff notifying him of Crocker’s arrival. “Gen Crocker has arrived here from New Mexico sick—He is ordered to report to Gen Thomas but can go no further,” Dodge declared. “Please change his order to report to me—I will send him home to wait the decision on his resignation which he will send on. He will have to go out of the Service. Would you like to be mustered if that is possible?”

Broken in health and unable to even make it the 300 miles or so to Nashville, Crocker turned westward in the direction of home, reaching Des Moines about a month later. When he arrived, Crocker sent off a hasty letter to Dodge: “I arrived home all safe and am improving rapidly, I think. At any rate, I am able to circulate to some extent.” In truth, he was only months away from his death.

He was ordered to Washington, D.C, during the summer of 1865. While staying at Willard’s Hotel, Crocker fell violently ill. As he lay protracted and delirious, Crocker scanned the room for his wife, but Charlotte was on her way from Des Moines. He passed away alone on August 26 at age 35. Crocker’s distraught wife reached Washington 24 hours after his death. She had missed the connection on the Chicago & Pittsburgh Railroad, delaying her arrival.

Hotel management moved Crocker’s body to another room and had it embalmed at their expense, allowing visitors to come and pay their respects. Colonel Peter T. Hudson of Grant’s staff escorted the body with a small detail of eight soldiers to Des Moines, where General Crocker’s remains were interred in early September. General Dodge was convinced that if Crocker had remained healthy, he “would have risen to the highest rank and command in the army.”

Grant never forgot his trusted subordinate. When he visited Des Moines at a reunion of the Army of the Tennessee in September 1875, he went for a morning carriage ride through the city on the day of his arrival. As the carriage passed down Fourth Street, Brig. Gen. Rollin V. Ankeny, a passenger in the carriage, pointed out Crocker’s old home. President Grant reportedly raised his hat and bowed his head in honor of the deceased general, uttering these short, but sincere, tribute: “There was a general, who was a true general, honest, brave and true.”

Frank Jastrzembski, who writes from Hartford, Wis., is the author of Admiral Albert Hastings Markham: A Victorian Tale of Triumph, Tragedy and Exploration. He runs “Shrouded Veterans,” a nonprofit mission to identify or repair the graves of Mexican War and Civil War veterans. For more information, see facebook.com/shroudedvetgraves

This story appeared in the August issue of Civil War Times.