Facts, information and articles about Manifest Destiny, an event of Westward Expansion from the Wild West

Manifest Destiny summary: In the 19th century US, Manifest Destiny was a belief that was widely held that the destiny of American settlers was to expand and move across the continent to spread their traditions and their institutions, while at the same time enlightening more primitive nations. And the American settlers of the time considered Indians and Hispanics to be inferior and therefore deserving of cultivation. The settlers considered the United States to be the best possible way to organize a country so they felt the need to remake the world in the image of their own country.

Many Americans believed that God blessed the growth of American nation and even demanded of them to actively work on it. Since they were sure of their cultural and racial superiority, they felt that their destiny was to spread their rule around and enlighten the nations that were not so lucky. The settlers firmly believed in the virtue of American people and the mission to impose their virtuous – mainly Puritan – way of life on everybody else. This rhetorical background served to explain the acquisition of territories or reasons to go to war, such as the war with Mexico in 1840s.

Manifest Destiny Goes Global

Outside the United States, the effects of manifest destiny were being seen in U.S. intervention in the Spanish-American war when Spain ceded the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico and Guam to the U.S. This was an expansion of U.S. territory as colonies rather than states and was another demonstration of growing U.S. imperialism.

The term of ‘Manifest Destiny’ first appeared in a newspaper article on the annexation of Texas in edition from July/August of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review in 1845. The author, John L. O’Sullivan used it to describe what majority of Americans at the time believed was their mission from God: to expand to west and bring the United States government to unenlightened people.

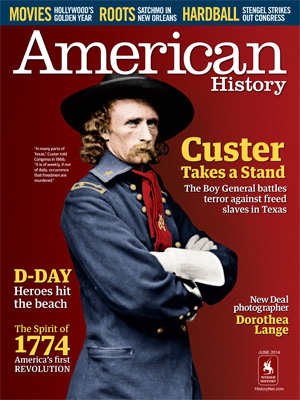

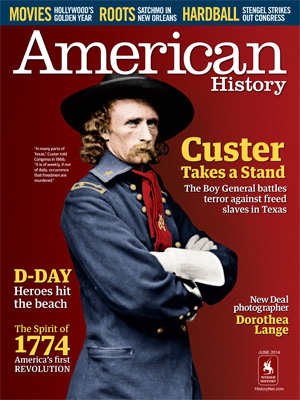

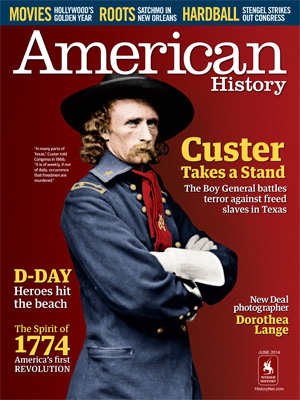

Articles Featuring Manifest Destiny From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

Olympian Fire: Dewey at Manila Bay

Dewey turned to Olympia’s Captain Charles Gridley and spoke the few words that doomed a Spanish squadron and opened the door to an American empire: ‘You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.’

In the early morning darkness of May 1, 1898, nine American warships sliced the weak chop of Boca Grande, one of two main passages into the Philippines’ Manila Bay. Distance and steel hulls attenuated the thumping of steam engines, and darkness swallowed the smoke from funnels as the ships’ crews crouched at their loaded guns, sweating in the tropical heat. Flanked by Spanish batteries on the islands of Caballo and El Fraile and tense with fear of mines thought to litter the channel, the American sailors were grateful for the darkness and the clouds that blocked moon and starlight.

Then, just as the ships passed El Fraile, flames flared from the funnel of the revenue cutter Hugh McCulloch. Instead of the good Welsh anthracite taken on by other vessels in British Hong Kong, the cutter’s bunkers held bituminous coal from its last port of call in Australia. Soot from the soft coal accumulated in the funnel and periodically burst into flame. Sailors cursed McCulloch as muzzle flashes marked a Spanish battery on El Fraile, and shell splashes stirred the waters of Boca Grande.

Four of the American warships opened fire and quickly smothered the enemy battery with shells as the column broke from the passage into the bay proper. On the cruiser USS Olympia, flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron and leader of the column, Commodore George Dewey watched. Orders already given, he spent long minutes waiting for gun flashes or dawn to reveal an enemy squadron. Perhaps Dewey filled a few of those minutes with memories of the past that had led him to penetrate the stronghold of his nation’s latest enemy.

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!Born in Montpelier, Vt., on Dec. 26, 1837, to Dr. Julius and Mary Perrin Dewey, George was the youngest of three boys. Mary died before George turned 6, so his upstanding and hardworking father became the central figure in his life. Other male figures also shaped Dewey, from public school teacher Z.K. Pangborn to his teachers at Norwich University and the professors and officers of the U.S. Naval Academy, to which he received an appointment in 1854.

George appeared to love neither the discipline nor the academics at Annapolis, as he piled demerits atop poor grades in his first year. Despite ranking just two places from the bottom of his class, he survived for a second year. Then, somehow, Dewey found a measure of maturity. Perhaps it was in the Bible classes he taught to local youths, in the letters he exchanged with his father or in the growing threat of civil war that haunted his nation. Whatever the reason, in June 1858 George and 14 others (all that remained of the 59 appointees of 1854) graduated. He, proudly, stood fifth in his class.

Following a two-year cruise on the steam frigate USS Wabash, flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron, Dewey took his examination for lieutenancy and was commissioned in the dark month of April 1861. Mere weeks later, he paced the deck of the steam frigate Mississippi, a 23-year-old executive officer untested in battle and assigned to blockade a rebellious Gulf coast. A year later, Dewey received his blooding, as Mississippi joined then-Captain David Farragut’s fleet in the assault on New Orleans.

Protected by a large garrison, the heavy guns of two forts and other batteries, and a small Confederate fleet that included the ironclad ram CSS Manassas—plus the Mississippi River currents, twists and treacherous snags—New Orleans seemed impregnable. But, as Dewey later wrote about the man who became his role model, “Farragut always went ahead.” From Farragut, Dewey learned not to overrate an enemy’s strength, enhanced as it usually was by fear and rumor. He also learned the import of decisive action when Manassas tried to ram Mississippi. Only a quick command from Dewey to the helmsman turned a potentially deadly direct hit into a glancing blow.

Over the course of the Civil War, Dewey was executive officer on six ships, eventually reaching the rank of lieutenant commander. Despite his service in four campaigns (efficiently and even heroically at times), Dewey wasn’t given his own command. But he did learn well the skills of command: leadership, intelligence, logistics, focus on the objective and decisive action. Unfortunately for Dewey, three decades would elapse before he could employ these skills to prove himself an outstanding fleet commander. Fortunately for the United States, Dewey persevered in his chosen career across those 30 years, despite the best efforts of his nation to virtually eliminate its own Navy.

As the years of fratricide ground toward Appomattox, the 700-ship U.S. Navy blockaded the Rebel coast, patrolled rivers, supplied Union forces and combed the high seas for the remaining Confederate raiders. But navies are expensive, and within days of the Confederacy’s final collapse, the Union began to divest itself of its old, converted merchantmen. Its ironclad monitors, designed only for coastal and riverine operations, followed—some sold for scrap but most laid up to be reactivated if war threatened. More ships met their end as Congress focused on Reconstruction, the Western frontier and internal expansion. By 1870 only 52 vessels (including auxiliaries) remained for sea and coastal duties, and those were far from the state-of-the-art warships then sliding down the ways in Europe.

The Navy returned to its overseas stations in the late 1860s. From those stations (established in and dependent upon foreign ports), lone ships cruised distant waters to show the flag and assist American merchantmen and civilians. There was no American “fleet” and little in the way of squadron training. Furthermore, the penny-pinching Congress relegated steam to secondary propulsion. Older warships (including USS Wampanoag, launched at war’s end and recognized as the world’s fastest warship under steam) saw their engine plants reduced in size and their spread of canvas increased. Naval regulations permitted the use of coal only under extreme conditions. Research into armament, armor and ship design languished. The state of strategic thinking matched the deterioration of warships and tactical capability. In essence, the United States returned to the outmoded doctrines of 1812, relegating its ships to coastal defense and commerce raiding.

This does not mean the Navy was inactive after the Civil War. In 1867 “gunboat diplomacy” opened two Japanese ports to American commerce; in 1871 a squadron attacked and destroyed several Korean forts, hoping to force that country to open its ports to trade; in 1883 the Navy protected foreign interests against Chinese rioters; and Marines and sailors debarked at various times in South and Central America to protect those citizens and their property. These were invariably small affairs—or at least incidents that did not threaten to escalate into war with major powers. Such was not the case in 1873 when Spanish authorities seized Virginius, a former Confederate blockade-runner supplying guns to Cuban rebels under a false American registry (see story this issue). The Spanish executed its crew, which included several Americans, notably Captain Joseph Fry, a Naval Academy graduate and former Confederate officer. American sympathies lay with the rebels and gunrunners, but cooler heads in Washington and Madrid avoided escalating tensions into war.

However, the Virginius Incident was a wakeup call for the naval establishment. In preparing for war, it found many of the mothballed monitors decayed beyond use. The following year, maneuvers incorporating reactivated vessels revealed a top fleet speed of less than five knots. Consensus held that one modern cruiser could sink the entire American force. Still, reaction from Congress proved slow and less than satisfactory.

In 1883 Congress finally authorized construction of four steel-hulled vessels: the protected cruisers Atlanta, Boston and Chicago (each featuring an armored deck at the waterline to protect magazines and engines from plunging fire) and the dispatch boat Dolphin. Known as the “ABCD Squadron” for their names or the “White Squadron” for their gleaming hulls and white canvas, these vessels captured the popular support needed for naval expansion. From 1885 to 1889, Congress authorized 30 additional warships, ranging from gunboats to the small battleships Texas and Maine. Building delays ensued when Congress mandated in 1886 that all naval vessels be built with domestic materials. At the time, American manufacturers could not provide the necessary guns, armor or steel plating. An immediate boost to industrial infrastructure set the first firm foundation for warship production in the nation’s history. Other warships, increasing in size and potential, followed the first 30.

As the new ships entered service, world events lifted American eyes from their own shores to blue waters. The close of the nation’s “frontier period” prompted the rise of a New Manifest Destiny, imperialistic in nature. But imperial ventures required a rethinking of naval strategy, and in 1890 Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, then-president of the U.S. Naval War College, provided a concise guide to that strategy in his seminal The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783. His treatise not only supported trade-based imperialism, it provided a naval theory and strategy that guided industrialized seafaring nations for several generations. With the great wars of France and Britain as his canvas, Mahan developed a theory of sea power rooted in squadrons of capital ships aggressively attacking the enemy’s navy or confining it to port. Naval officers worldwide welcomed this concept of firepower projection (and, of course, the many ships required to carry that firepower), while the eyes of statesmen glistened at the thought of colonies to be gained and raw materials to be exploited.

Cuba and the remaining Spanish possessions in the Caribbean attracted American interest for a variety of reasons. Some pointed to Spanish cruelty and the brutalized people who desperately sought the caress of democracy and the guidance of Republican values. Navalists sought an American base in the Caribbean from which to enforce the old Monroe Doctrine. Industrialists desired sugar and markets. Shipping magnates resented searches by Spain’s Guardia Costa and navy alike, particularly when those searches involved seizure of goods being smuggled to Cuban rebels. Last, the American press wanted to sell newspapers—and greedy publishers did not hesitate to juggle facts to ensure those sales. By Feb. 15, 1898, fertile ground existed for war between the United States and Spain. All that was needed was a spark, and the spark that ignited a coal bunker and the adjacent magazine on the USS Maine in Havana’s harbor served nicely, especially when a naval court of inquiry quickly blamed the resulting deaths of some 270 American sailors and officers on the explosion of a Spanish mine.

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!As the Navy evolved, George Dewey quietly persevered. Many officers abandoned the slow promotion schedule and other frustrations of service life, turning their talents to the civilian world and its monetary rewards. But something drove Dewey, likely the desire to make his mark on history in the names of his heroes, Dr. Julius Dewey and Admiral David Farragut. Civilians seldom garnered such fame.

Finally, in 1870 Dewey was given his first command, the sloop-of-war USS Narragansett. A few years later, as the Virginius Incident unfolded, Narragansett was assigned to survey the Pacific Coast of Mexico and Lower California. Dewey’s officers and men worried they would miss the brewing war, but Dewey smiled and predicted they would simply steam across the Pacific and capture Manila. No one hearing his words could imagine their prophetic nature.

A full captain by 1884, Dewey served in various capacities before becoming head of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting in 1889, followed by stints as president of both the Lighthouse Board and the Board of Inspection and Survey. His energy, efficiency, professionalism and skillful leadership amidst the often-confused rush to build modern warships did not go unnoticed. Yet, Dewey felt some degree of despair when he reached the permanent rank of commodore in 1896, only four years from forced retirement. No war seemed in the offing, and should war break out, he knew that other deserving officers waited for fleet and squadron commands.

But Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt had marked Dewey as a man of action. Roosevelt expected war with Spain and felt that the Asiatic Squadron, operating some 7,000 miles from homeports, needed a strong, aggressive hand at the helm. Roosevelt pressured President William McKinley to appoint Dewey to the key command, and in October 1897 McKinley ordered the secretary of the Navy to make it so. Fate waited to present Commodore Dewey with his chance for greatness.

Dewey did not wait on fate. Gathering every available scrap of information on the Philippines to supplement a file provided by the Navy, he ordered ammunition rushed to his squadron in Yokohama, Japan. Dewey arrived in Yokohama in late 1897, and his men loved him from the beginning. Extremely fit, handsome, and always neatly dressed, their commodore seemed as comfortable with the common Jack as with his officers. His white walrus mustache and piercing blue eyes seemed to dominate the decks of his flagship. Within days of his arrival at Yokohama, this outstanding leader had gained the full support of his gathering squadron—and well that he did, for much hard work remained to ready his people and ships for war.

As soon as sufficient ammunition arrived in Yokohama, Dewey ordered his squadron to make for Hong Kong. An alert from Roosevelt followed news of the sinking of Maine in February. As Dewey waited for his remaining ships to concentrate in Hong Kong, he plumbed the American consul in Manila for information. He left no stone unturned, even dressing an aide as a civilian to wander the docks and solicit information from incoming vessels. As his warships arrived, Dewey purchased the freighter Zafiro and the collier Nanshan from British sources and registered them as American merchant vessels, so they could enter neutral ports should war be declared. (The closest American base lay 7,000 miles away.) He then dry-docked each of his ships for last-minute scraping, repair and a coat of dark gray paint.

Finally, on April 25, Dewey received a telegram confirming the declaration of war. Within hours the British invited his squadron to leave neutral Hong Kong. As the Asiatic Squadron steamed from port, its officers and men understood the sortie would end in absolute victory or utter defeat. They threw themselves into battle preparations, stripping flammable material from the ships, dry firing guns, studying signals and planning for damage control.

Off the Philippines on April 30, Dewey dispatched two ships to search Subic Bay, but the Spanish fleet had abandoned it, as it lacked supporting land batteries. The commodore called together his captains before sailing on to Manila. He knew the islands guarding Boca Grande held at least six guns that outranged his own. He also knew the Spanish expected his fleet and had possibly mined the channel. Given the circumstances, Dewey felt only an audacious night passage could succeed—and he planned to lead the column in Olympia. Like his hero Farragut, Dewey brooked no argument from his gathered captains.

As midnight approached, Olympia led the protected cruisers Baltimore and Raleigh, gunboats Petrel and Concord, protected cruiser Boston and revenue cutter Hugh McCulloch into the passage, followed closely by Zafiro and Nanshan. Following the burst of inaccurate fire from the quickly silenced battery on El Fraile, the column broke into Manila Bay. Dewey slowed to 4 knots to delay until dawn his engagement with the Spanish squadron of Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. Some of Dewey’s men even managed to nap at their guns before the galley delivered hot coffee at 0400.

Commanding from aboard the unarmored cruiser Reina Christina, Montojo knew that his seven old vessels did not rate half the displacement of the modern American ships and that his largest 6.2-inch guns could not match the Americans’ 8-inchers. The Spanish admiral positioned his ships in a half-moon formation across the harbor at Cavite rather than subject the Manila waterfront to “overs” from an American attack. The old wooden cruiser Castilla could not maneuver, but would still attempt to support the small cruisers Isla de Cuba, Isla de Luzon, Don Antonio de Ulloa and Don Juan de Austria. The gunboat Marques del Duero completed Montojo’s defensive line. In an effort to offset American firepower, the admiral anchored lighters alongside his larger vessels to absorb enemy fire. Gun emplacements at Sangley Point supported the west flank of the squadron. Four additional gunboats, stripped of weapons to fortify the harbor, hid in the shallow waters behind Cavite. Warned by telegraph at 0200 of the American approach, Montojo had few illusions about the coming battle, but he sent his sailors to their guns to fight with honor in defense of Spain.

Sending his collier and freighter clear under the escort of Hugh McCulloch, Dewey first cruised the Manila waterfront in search of the Spanish squadron. At 0505 batteries near Manila opened on the Americans; Boston and Concord answered their inaccurate fire. Shortly afterward, Olympia observed explosions near Cavite, some two miles away. Dewey assumed panic on the part of the Spanish, but Montojo had ordered a minefield detonated to provide maneuver room for his flagship. At 0515 both ship and shore batteries at Cavite opened on the Americans. Dewey, with no rounds to spare, held his fire and maintained a converging course for the next 25 minutes. Then, at a range of 5,000 yards, Dewey turned to Olympia’s Captain Charles Gridley and spoke the few words that doomed a Spanish squadron and opened the door to an American empire: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.”

One minute later, Olympia’s four 8-inch guns spoke. Its 5-inchers and the smaller rapid-fire guns of the starboard battery quickly added their din and smoke to the combat, a scene repeated as each American vessel spotted the enemy. Dewey’s squadron exchanged fire with the Spanish ships for more than an hour, describing almost three complete circles in front of the enemy position at ranges from 2,000 to 5,000 yards. Two Spanish torpedo boats raced toward the squadron—one was sunk by American fire, while the other, wreathed in flames, beached itself. Don Juan de Austria also attempted to close on the American fleet before concentrated fire saw it off. Then Montojo ordered Reina Christina into the harbor in a valiant attempt to ram Olympia. Heavy shells slammed into it, and the Spanish flagship limped back to its anchorage.

At 0730 Dewey received word that each of Olympia’s 5-inch guns was down to 15 remaining rounds. Fearing his other guns might also be low on ammunition, and prevented by heavy smoke from accurately assessing the damage he’d inflicted on the Spaniards, Dewey reluctantly signaled his ships to withdraw. As firing ceased, it became obvious he had severely punished the Spanish squadron, leaving some vessels in flames and others listing or settled in the shallow harbor.

With Reina Christina’s steering destroyed and magazines flooded, Montojo ordered the vessel scuttled and switched his flag to Isla de Cuba. As the Americans paused to enjoy a belated breakfast, he surveyed the wreckage of his squadron. Don Antonio de Ulloa had settled in the harbor, its captain and half its crew dead or wounded. Old Castilla, beaten to pieces and afire, sank at anchor. Both Isla de Luzon and Marques del Duero had lost men and guns, and little fight remained in them. Montojo ordered all able vessels to retreat to the bay behind Cavite and fight if possible, scuttle if not. By the end of the day, the Spanish admiral listed all ships lost and 381 men dead or wounded.

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!Aboard Olympia, Dewey had been delighted to discover the message regarding his ammunition reversed: Each gun had expended only 15 rounds. Even more astounding, only nine men had suffered wounds during the action (another, Hugh McCulloch’s chief engineer, died of a heart attack on the approach to Manila). After allowing his men to finish a well-earned breakfast, Dewey ordered a final pass at the Spanish squadron. Only one vessel, Don Antonio de Ulloa, showed any sign of resistance, and that was quickly eliminated. Fire from Baltimore silenced the guns on Sangley Point and a battery near Cavite. With no apparent resistance remaining, Petrel’s captain accepted the surrender of Cavite’s garrison, several gunboats and a transport. By mid-afternoon of May 1, 1898, the Battle of Manila Bay was over.

Despite open rebellion, led by Filipino Emilio Aguinaldo and supported by Dewey, and the closure of its harbor by American warships, the Spanish garrison at Manila managed to stave off starvation and defeat until the arrival of American troops later that summer. Commodore (soon to be Admiral) George Dewey had at last emulated his hero, David Farragut, and laid the ghost of his father to rest by crushing the Spanish squadron. But on August 13, as Manila surrendered, he became forevermore the man who first opened the door for an imperial America.

For further reading, Wade G. Dudley recommends: A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899–1902, by David J. Silbey. To experience the Spanish-American War through the words of the participants (and to explore USS Olympia), visit the Spanish-American War Centennial Web site.