When Brigadier General Norman “Dutch” Cota landed on Omaha Beach at 7:25 a.m. on June 6, 1944, he saw death, destruction, and defeat. From the bluffs overlooking the shore, German machine guns and rifles raked the beach, and artillery and mortar shells added to the mayhem. Dead and wounded American soldiers lay sprawled on the sand and floating in the water. Discarded weapons, life vests, and personal effects were strewn about, and disabled tanks burned fiercely.

The dazed, dispirited, and exhausted soldiers who had made it across the beach huddled by the seawall beneath the bluffs, “inert, leaderless and almost incapable of action,” as a U.S. Army after-action report described, their weapons fouled by sand and water and their resolve shaken by the horrors they had seen. “The crusade in Europe at this point was disarmed and naked before its enemies,” Captain Charles Cawthon of the 29th Infantry Division recalled.

What Cota saw didn’t surprise him. He knew that landings rarely follow the script, and this was no ordinary landing. It was the largest, most complex invasion ever attempted and was, the planners conceded, “fraught with hazards, both in nature and magnitude.” As Cota scanned the beach, he saw that everything that could go wrong had gone wrong. He knew that it was up to him—and the men by the seawall—to somehow make the landing work.

THE ALLIES HAD BEEN PLANNING the invasion of France, dubbed Operation Overlord, for more than a year. They targeted spring of 1944 for the assault phase, Operation Neptune, choosing a 50-mile stretch of the Normandy coastline as the landing site. British and Canadian troops would assault three beaches—Juno, Sword, and Gold—while American troops would hit two to their west, Utah and Omaha.

Four-mile-long Omaha Beach, also known as Beach 46, shaped up as the toughest nut to crack. Its terrain was ideal for defense. At low tide, invading troops would have to cross 300 yards of open beach to reach the cover of a four-foot-high seawall. Steep sandy bluffs, rising 100 to 170 feet, overlooked the shoreline and dominated the landscape. The Germans heavily fortified these bluffs, focusing maximum firepower on the beach. Gunners in eight casements— with concrete walls three or more feet thick and housing guns 75mm or bigger—85 machine-gun positions, 35 pillboxes, 38 rocket pits, and six mortar positions all trained their sights on the shore, while ditches, walls, barbed wire, and minefields blocked Allied troops and vehicles from climbing the bluffs. But Omaha Beach had to be taken to avoid leaving a vulnerable gap between Utah Beach directly to the west and the three British-Canadian beaches to the east.

In February 1943, Norman Cota, a 1917 West Point graduate, was given his first star and assigned to the Allied invasion-planning staff at Combined Operations Headquarters. As chief of staff of the 1st Infantry Division, he had helped plan and execute the successful North Africa landings in November 1942. He was all infantryman, as skilled at leading a squad as at planning an invasion.

As the planning for Neptune shifted into gear in June 1943, Cota warned his colleagues that the invasion plan must be “thoroughly honest and simple” and rely “on the experience of those who have tried this thing before.” Above all, he warned, it must include a sufficient margin of error—what he called “factors of safety”—for the unexpected mishaps that inevitably occur. The greatest danger, he believed, was overthinking the plan. A multitude of British and American army, navy, and air force officers had a finger in the invasion pie and, Cota said, “nothing can move so fast from the simple to the complex as a Combined Operation.”

THE RESOURCES COMMITTED to the operation were staggering—132,000 soldiers and 23,000 paratroopers would land on D-Day alone, supported by nearly 12,000 planes and more than 6,000 ships. If the invasion failed, it would be many months, at least, before the Allies could gather the resources to try again. “We cannot afford to fail,” Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower emphasized.

The Allies had made successful landings in North Africa and Italy, but none had involved beaches as heavily defended as those in Normandy. The only attack on a well-fortified coast—the raid on the French port of Dieppe in August 1942—had failed, with more than half the attackers killed, wounded, or captured. No strong pre-invasion bombardment had preceded the Dieppe operation, and planners pegged that as the fatal flaw. In any future assault on France, warned British commodore John Hughes-Hallett, naval commander at Dieppe, “intensive preparations by means of air and sea bombardment are essential in order to soften the defences.”

The invasion architects had considerable firepower at their disposal, and they intended to use it. At Omaha Beach, the battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas, three cruisers, and a dozen destroyers would blast the defenses, and 480 B-24 Liberator heavy bombers were assigned to pound the German positions. The assault would also rely heavily on a new but unproven weapon: 64 duplex-drive (DD) amphibious Sherman tanks that would swim to shore to provide critical troop support.

The planners knew that firepower had limitations. U.S. Army Air Forces Brigadier General Robert C. Candee stressed that it would be “highly dangerous for me to promise in any way” that bombing could destroy the beach defenses. Likewise, U.S. Navy Commander Elliott B. Strauss warned that naval gunfire “cannot be depended upon to permanently reduce well emplaced and protected shore batteries.” The most that could be expected, the brass were told, was stunning the defenders with blast concussions, temporarily neutralizing them as the first waves of infantry stormed ashore.

These limitations steered the planners toward what Cota had warned of: a complex plan with little margin for error. On Omaha Beach, the first wave had to land before the dazed Germans regained their wits. To accomplish this, the 40-minute naval bombardment and the 25-minute bomber strike would end at 6:25 a.m., and the first assault troops would land at 6:31 a.m., only six minutes later. If the first wave of troops arrived too late, the defenders would be ready to meet them with withering fire, but an early arrival risked friendly casualties from bombs or naval shells that fell short. The air force estimated that as many as 8 percent of its bombs would drop in the water among the landing craft.

BY THE TIME THE PLANS were finalized, Cota was no longer part of the process. In October 1943, he was assigned to the 29th Infantry Division—with the 1st, one of the two divisions slated to hit Omaha Beach—as assistant division commander. Cota spent the rest of 1943 and early 1944 training the 29th, which had yet to see action. A rugged and stocky man, Cota was a ubiquitous presence on training exercises, encouraging and instructive. He was universally known as “Dutch,” a nickname he picked up playing high-school football in his native Massachusetts.

On April 9, 1944, two months before D-Day, an unexpected development complicated a plan that already had little room for error. Aerial reconnaissance showed the Germans constructing beach obstacles concentrated off Omaha Beach, something the invasion planners had previously believed the enemy lacked the resources to do.

By D-Day, these obstacles were many and varied. Farthest from the shore were about 200 Belgian gates, seven-by 10-foot iron barricades, many with mines attached. Next were about 2,000 wooden or concrete poles pointed seaward, again with mines or artillery shells often attached. The finishing touch was 1,050 hedgehogs—six-foot steel bars welded together at right angles—placed near the shoreline.

These obstacles posed a serious threat because they could damage any landing craft that hit them, and those armed with mines or artillery shells could blow boats apart. At the very least, the barriers could delay or prevent landing craft from reaching the shore, upsetting the split-second timing needed for the men to land before the enemy had recovered from the bombardment. Until these obstacles were removed, troops under fire would have to wade more than 50 yards through water knee-deep or higher to reach the shore. Then, soaked, exhausted, and still under fire, they would have to cross the beach to the seawall.

To meet this threat, the planners assigned 24 demolition teams to blow 16 50-yard-wide gaps through the obstacles, but the timing was tight—perhaps too tight. The demolition teams would land at 6:33 a.m., only two minutes after the first wave, and would have to finish their work in less than half an hour, before the bulk of the assault troops began landing at 7 a.m. and before the rising tide submerged the barricades.

Nevertheless, Eisenhower was confident. “If our gun support of the operation and the DD tanks during this period are both highly effective, we should be all right,” he wrote on June 3, 1944. “The combination of under-sea and beach obstacles is serious but we believe we have it whipped.”

Cota had his doubts. His experience had taught him not to count on any landing going according to plan, and he was skeptical of this plan’s split-second timing because he knew “confusion and chaos are inherent in the very nature of the operation.” He wasn’t alone in this thinking. Colonel Paul R. Goode of the 29th Infantry Division briefed his regiment by tossing aside the bulky invasion plan. “Forget this goddamned thing,” he told his men. “There ain’t anything in this plan that is going to go right.”

On June 5, 1944, aboard the attack transport USS Charles Carroll, Cota gave his staff, self-dubbed the “Bastard Brigade,” a no-holds-barred briefing on what to expect the next morning. Cota anticipated that the air and naval bombardments wouldn’t meet expectations, and he assumed the landing craft would arrive late. Gaining a beachhead would be no easy task, he believed, but leadership, courage, and quick thinking would carry the day. “We must improvise, carry on, not lose our heads,” he emphasized. He knew that soldiers, not plans, win battles.

BY THE TIME COTA and his aides landed on the Dog White section of Omaha Beach the next morning, his predictions had come terribly true. The invasion plan had gone hopelessly awry, and the landings had become, said Neptune’s ground commander, British General Bernard Law Montgomery, a “very sticky party.” What began as an organized assault had “deteriorated into a struggle for personal survival,” according to one 29th Infantry Division after-action report.

Strong winds, rough seas, and overcast skies played havoc with the landings. Because cloud cover prevented bombardiers from seeing their targets, they had to bomb by radar. Air commanders lacked confidence in this method for close support of ground troops, so they ordered bombardiers to hold their payloads for an extra five to 30 seconds to avoid hitting friendly landing craft, which would be as close as 400 yards from the shore. This caused the B-24 Liberators’ 1,286 tons of explosives to fall far beyond the Germans’ beach defenses. A later investigation confirmed that there was “no evidence of bomb strikes on or near the target areas or anywhere in the vicinity of the beach,” something angry soldiers already knew.

“The Air Corps might just as well have stayed home in bed for all the good that their bombing concentration did,” Lieutenant Colonel Herbert C. Hicks Jr. complained in his after-action report, and one infantryman wrote home that the airmen “might have done better if they had landed their planes on the beach and chased the enemy out with bayonets.” The air force later conceded that the pre-invasion bombardment had “afforded little support to the landing operations.”

The Texas had fired nearly 700 14-inch rounds and the Arkansas more than 700 12-inch shells, but the navy neither destroyed nor neutralized the defenses. The thick concrete casements survived all the navy threw at them, and most “did not show signs of direct hits nor of any shells exploding sufficiently close to be effective,” noted Colonel E. G. Paules of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers the following month. Many fortifications were so cleverly hidden that they were invisible to aerial or seaward observation, and all were “exceedingly difficult to detect,” wrote Admiral John L. Hall Jr., the naval commander at Omaha Beach, in a report directly after the assault.

Choppy seas caused the untried DD tanks to fail. Only about half of the 64 DD tanks made it ashore; the others sank or were knocked out by artillery fire. The German defenders, thought to be of low quality, had been augmented with veteran troops. The beach obstacles remained in place because they were “much more numerous than Intelligence reports had indicated,” Admiral Hall reported, and because nearly half the demolition men became casualties. The biggest impediment to demolition, however, was that soldiers—many severely wounded—clustered behind the barricades to shelter themselves from the deadly small-arms fire.

Strong currents had prevented the first waves from landing as planned. “All semblance of wave organization was lost,” Admiral Hall noted, and boats landed individually—often late—giving the Germans time to regain their wits after the naval bombardment and focus their fire on the men leaving each craft. The first waves were slaughtered, with “men being killed like flies from unseen gun positions,” reported Major Stanley Bach, a member of the “Bastard Brigade.”

COTA ALMOST DIDN’T make it ashore. His boat, LCVP 71, hit a mined wooden pole. “Kiss everything goodbye,” he thought as he braced for the explosion, but the mine fell harmlessly into the water. Cota and his staff landed 50 yards from shore in knee-deep water and quickly came under fire. After briefly taking cover behind a tank, Cota made it to the timber seawall, where he found disorganized groups of soldiers taking cover. The seawall protected them from small-arms fire, but not from mortars; shrapnel the size of a shovel blade killed a man near Cota.

Huddled by the seawall, Private William Stump craved a cigarette, but his matches were soaked, so he asked the soldier next to him for a light. When that soldier turned towards him, Stump was startled to see he was a general. “Sorry, sir,” he stammered. “That’s OK, son, we’re all here for the same reason,” Cota said as he lent Stump his Zippo lighter.

Staying by the seawall was suicide, so Cota looked for a way to get the men on the move. Although admittedly “scared to death,” he walked along the beach, seemingly oblivious to enemy fire while encouraging the troops forward. The prone soldiers took notice. “I guess all of us figured that if he could go wandering around like that, we could too,” said Sergeant Francis Huesser.

Cota rallied a group of U.S. Army Rangers. “You men are Rangers, I know you won’t let me down,” he said. Their captain intervened. “Hey, Bud,” he barked. “This is my outfit—I’ll take care of it.” To many generals that would have been a court-martial offense, but Cota saw an angry junior officer ready to lead and the Rangers soon moved forward.

Cota rallied a group of U.S. Army Rangers. “You men are Rangers, I know you won’t let me down,” he said. Their captain intervened. “Hey, Bud,” he barked. “This is my outfit—I’ll take care of it.” To many generals that would have been a court-martial offense, but Cota saw an angry junior officer ready to lead and the Rangers soon moved forward.

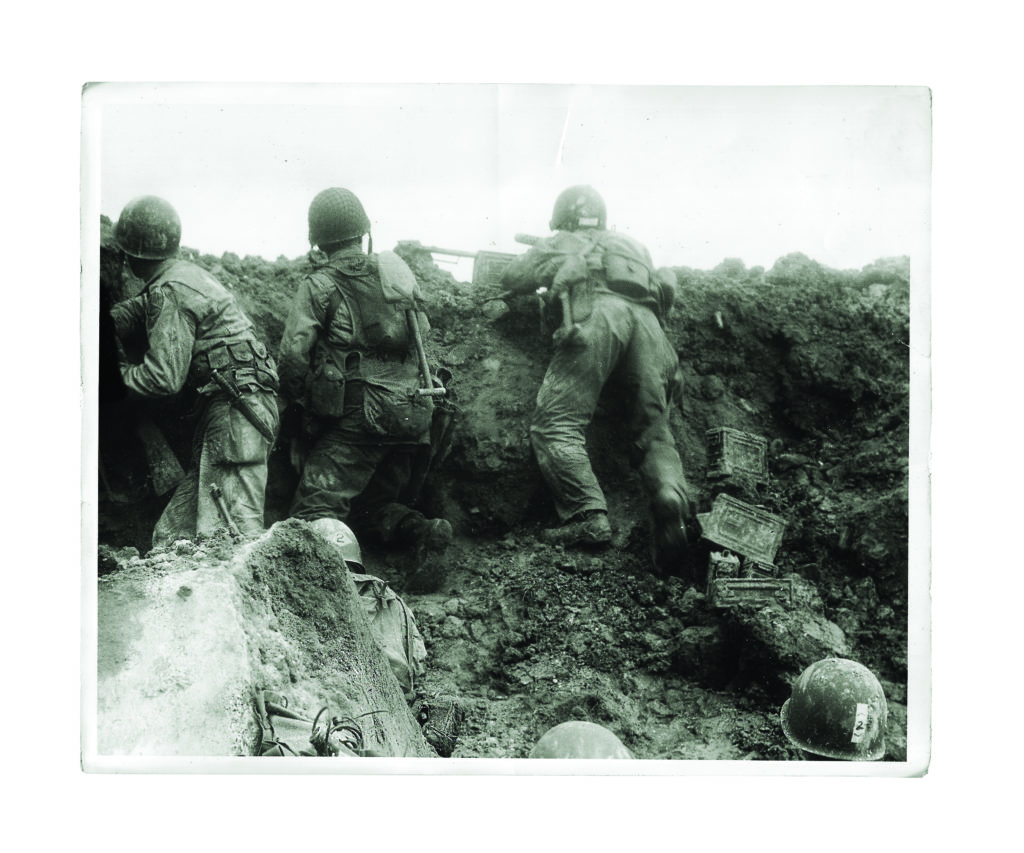

Cota knew he, too, had to lead. He crawled past the seawall, found a good position, and put a soldier with a Browning Automatic Rifle there to provide covering fire. He had another soldier use a Bangalore torpedo to blow a hole in the double-apron barbed wire blocking access to the bluffs. The first soldier through the gap was hit by machine-gun fire, writhing on the ground screaming for a medic and his mother until he died. This rattled the already-jarred troops; Cota knew something dramatic was needed, so he charged through the gap and made it. Others followed. A mortar shell landed nearby, killing two men near Cota and throwing him up the bluff. At 51, Cota was perhaps the oldest man on Omaha Beach, but he popped up unharmed.

Using a communications trench for cover, Cota led a small group up the bluff. At the top, machine-gun fire from across a field stalled the advance. Cota had several men lay down covering fire, and he tried to find a sergeant or lieutenant to lead an attack. “None of the leaders seemed to be in evidence, and his exhortations were not too successful,” noted Cota’s aide, Lieutenant Jack Shea. So Cota himself led the charge, and the Germans fled. This was, historians Stephen Ambrose and Joseph Balkoski believe, the first successful infantry assault of the Allies’ Normandy campaign.

Cota’s party advanced to the nearby town of Vierville-sur-Mer. About 500 yards from town, a machine gun opened up. Cota sent a patrol to flank the gun, and the Germans ran away. By 10 a.m., a few other troops had come up the bluffs. “Where the hell have you been, boys?” was Cota’s cheerful greeting.

By noon, Cota was concerned that no vehicles had come up from the beach to Vierville, so he led a five-man patrol back to the shore to investigate. Germans fired on them from a nearby cavern; in return, a “dozen rounds of carbine and pistol fire sufficed to bring five Germans down,” Lieutenant Shea said. The prisoners were, one observer noted, a “sorry looking bunch in comparison to our well-fed and equipped men.” Continuing toward the beach, the patrol encountered mines. Cota had one of the prisoners lead his men through the minefield, with the Americans careful to follow the German prisoner’s footsteps. Cota’s patrol passed the bodies of more than 30 29th Infantry Division men killed trying to advance up the bluff.

Cota saw the reason for the hold-up: a thick concrete antitank wall blocked the road. Engineers said they lacked explosives to demolish it, but Cota noticed a bulldozer tank nearby loaded with TNT. When no one volunteered to drive the bulldozer to the antitank wall, he challenged the men. “Hasn’t anyone got guts enough to drive it down?” he asked. A young soldier came forward, and Cota slapped him on the back with a hearty “That’s the stuff,” adding, “Goddamit, get moving.” Soon, the wall was gone. Cota regretted not getting the volunteer’s name so he could put him in for the decoration he deserved.

On the way back toward the front, Cota had his first chuckle of the day when he came across a sailor—whose landing craft had been shot out from under him—carrying an unfamiliar rifle in his hands. “How in hell do you work one of these?” he asked, complaining that this was just why he had joined the navy, to avoid “fighting as a goddamn foot-soldier.”

By late afternoon, the acute crisis had passed. Troops, vehicles, and supplies were streaming ashore and advancing up the bluffs. By the end of the day, 34,000 men had landed on Omaha Beach and the crusade in Europe was back on track. The price, however, was high: 2,400 dead, wounded, or missing.

THE SOLDIERS who were at Omaha Beach knew what had made the high command’s plan work. “Navy can’t hit ’em—air cover can’t see ’em—so infantry had to dig ’em out,” Major Bach wrote in notes scribbled that afternoon. To Colonel Paules, “those bluffs were captured and those exits opened solely through the plain undaunted heroism of those infantry teams of the 1st and 29th divisions and their attached engineer units…. The two cemeteries at Omaha Beach speak eloquently of the type of men who were there that day.”

What tipped the scales, Captain John C. Raaen of the 5th Ranger Infantry Battalion wrote in a letter home, was the “magnificent leadership of a few officers like General C.,” who put their lives on the line “when the chips were down.” Cota had improvised, carried on, and kept his head. On June 29, 1944, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his “superb leadership, personal bravery, and zealous devotion to duty” in rallying the troops and leading them up the bluffs. But to Cota, it was the men on the beach who deserved the credit. “Believe me,” he wrote to a friend in 1949, “they were the only reason that enabled an old crock like myself to shake fear loose and ‘Roll On.’” ✯