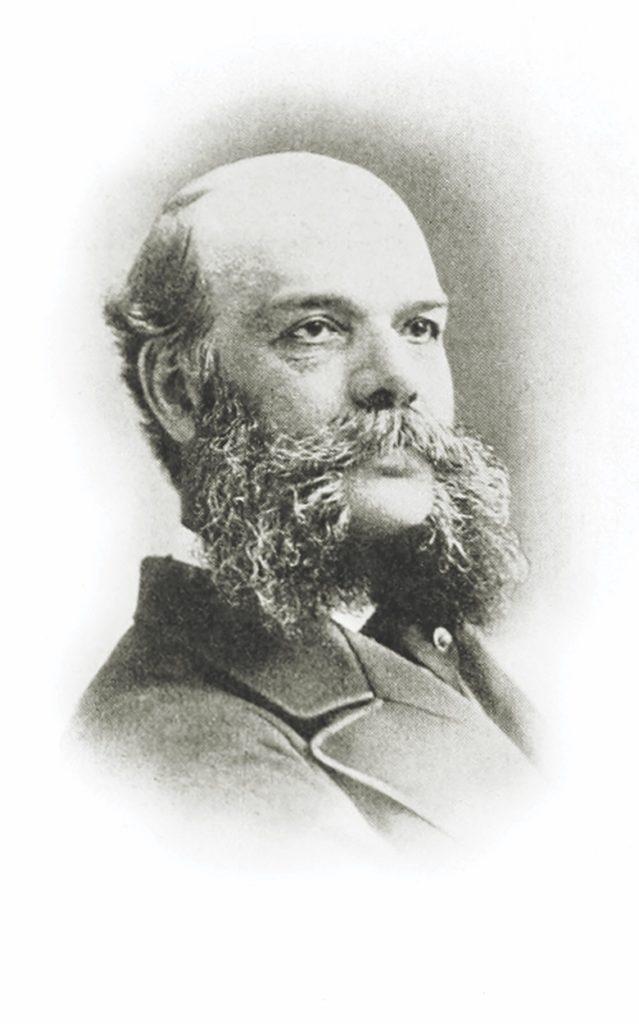

The tall, sad-faced, New Jersey Quaker carried himself more like a career diplomat than a notorious spymaster. In reality, Thomas Haines Dudley was both.

A passionate abolitionist, successful lawyer, and Republican Party activist, Dudley helped orchestrate Abraham Lincoln’s nomination as the party’s candidate in the 1860s presidential election. As a reward, he had his choice of serving as the American minister in Japan or in a lesser position as consul in Liverpool, England. Dudley chose Liverpool because he wanted to contribute to the Union cause during the war and believed he could get dependable medical treatment there for his chronic irritable bowel. While Dudley fulfilled his diplomatic duties and received the medical treatment he needed, his most important role was organizing and running what became the Union’s most successful spy network on the Civil War’s most hotly contested foreign battlefield.

Dudley would fight his battles mostly in the shipyards lining the banks of the River Mersey and in Liverpool, its port city. That prosperous metropolis was a hotbed of Confederate sympathizers and ground zero for the Confederacy’s all-out effort to build a blue-water navy. More than 90 percent of the cotton entering the United Kingdom landed on Liverpool’s docks, and more than 80 percent of that cotton came from the American South. In an early dispatch to Secretary of State William Seward, Dudley wrote, “the great mass of the residents of [Liverpool] is and has been against the North and in favor of the South. This feeling is now deep and bitter.”

To keep the profitable cotton trade going and its war-making capability alive, the Confederacy needed fast blockade runners, commerce raiders to sink Union merchant shipping, and state-of-the-art warships to break the naval blockade strangling the South. The Confederacy’s shipbuilding facilities were insufficient to meet its needs, but England’s shipyards could make up that deficit. President Lincoln needed someone to report on the Confederacy’s progress and hamper its efforts. Dudley was soon at the heart of the war’s European intrigues.

When he arrived in Liverpool in November 1861, Dudley found Confederate agents hard at work—the keel of one commerce raider already laid, thanks to the work of James Dunwoody Bulloch, head of the South’s secret service throughout Britain. He had arrived in Liverpool five months earlier, armed with a $2 million loan guarantee backed by a prestigious Liverpool firm and a mandate to build ships and buy naval stores.

Dudley came armed, too, and technically had the law on his side. England’s Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819 forbade the equipping and arming of ships in British ports for the use of belligerents with whom that country was at peace. But getting Britain to enforce the law was a different matter, and Bulloch was particularly adept at circumventing any legal constraints. Often he simply contracted for a ship and had an English captain and skeleton crew sail it on a “trial run.” Once outside the reach of British law, the ship would be armed, fitted out, and crewed with Confederate sailors at a foreign port. Or Bulloch would have the builders claim the ship was a mere merchant vessel or was destined for another nation’s navy and therefore legally built in England.

Proving Bulloch’s many subterfuges false was complicated and time-consuming. Dudley’s efforts to gather evidence and submit affidavits were made more difficult by the Southern sympathies of the British government under Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and his foreign secretary, Lord John Russell. Legal foot-dragging by bureaucrats, judges, and customs officials at every level of government further frustrated Dudley’s efforts to prevent many ships from escaping. To gather information in support of his legal cases, Dudley at first used a small network of agents and informers begun by his predecessor. But he soon found that to keep track of the Confederacy’s expanding ship-building program, he would need more spies and a lot more money to pay them. With the help of a private detective, Michael McGuire, Dudley set out to build a coordinated intelligence network of sympathetic British shipyard workers, Southern turncoats, tavern keepers, and a motley assortment of dockyard denizens who prowled Liverpool’s waterfront.

A dispatch from Dudley to Seward about a ship being built on the Mersey portrayed how one of the Confederacy’s schemes worked: “The builders say she is intended for the Italian Government….I am afraid she is intended for the South. She has one funnel, three masts, bark rigged, eight portholes on each side and is to carry sixteen guns….Her armament is not yet on board and the appearances indicate that she is to leave Liverpool and receive [cannon and shot] at some other place.”

Dudley was describing Oreto, the first Confederate commerce raider being built in England, which would become known as CSS Florida and would ravage Union merchant shipping over the next three years, taking more than 60 prizes worth in excess of $4 million (10 times what it cost to build it).

Bulloch also had a second commerce raider under construction in Birkenhead, across the Mersey from Liverpool. After failing to prevent Florida from sailing, Dudley ramped up his efforts to stop this ship, designated No. 290. His operatives frequented taverns and other places where dockyard workers congregated, gathering timely information. A May 1862 report to Seward warned, “She will be when finished, a very superior boat. The order when given was to build her of the very best material and in the best and strongest manner. There is no doubt…she is intended for the Rebels.”

This raider, 210 feet long and weighing more than 1,000 tons, was even larger than Florida. Powered by twin 300-horsepower engines, it could steam at 12 knots, easily fast enough to overtake any Union merchantman.

This time the builders claimed the ship was destined for the Spanish government even though Dudley’s massive documentation clearly demonstrated otherwise. But British officials disagreed and found no credible evidence that No. 290 was destined for the Confederacy. Dudley was so sure, he traveled to London on June 21 to personally present his evidence to American Ambassador Charles Francis Adams. Even a personal note from Adams to Foreign Secretary Russell failed to prod the British government into action. On May 14, 1862, No. 290 slipped down the ways and a month later made a trial run. Dudley continued to supply British authorities with damaging evidence, hoping to prevent the ship’s eventual departure, but to no avail. On July 31, No. 290, now called Enrica, weighed anchor for its final trial run. It never returned to England. On August 21, 1862, Enrica arrived in the Azores, where Captain Raphael Semmes took command and christened the ship CSS Alabama. Until sunk off the coast of France in June 1864, Alabama captured 64 Union vessels worth more than $5 million.

Despite the setbacks, Dudley continued to gather evidence of English complicity. His agents infiltrated social clubs, learning the names of blockade runners and their dates of sailing. He regularly supplied Seward with manifests of blockade runners departing for Southern ports and also initiated a successful propaganda campaign supporting the Union’s war aims, wrote newspaper articles, pamphlets, and letters to editors and sympathetic British parliamentarians.

Dudley’s expanded espionage network, now numbering more than 100 informants, paid dividends when he learned about two ironclad warships being built. Known only by the code numbers 295 and 296, they were designed to be superior to any Federal warship afloat. Despite attempts to keep the ships a secret, Dudley’s spies learned their dimensions. Both would have 200-foot keels and “a strong ram of wrought iron projecting about 8 feet just under the water line.” In a March 1863 report, Dudley observed that “no expense is being spared,” concluding direly: “You must not deceive yourselves…they will have more power and speed probably than any ironclad…that has yet been built.”

Seward made Dudley’s confidential report public. Its dramatic revelations energized Congress, and the American press began a public relations campaign demanding that England seize the ships. On September 5, 1863, Adams sent a strongly worded note to Foreign Secretary Russell indicating that the first ironclad was ready to sail and the British government’s failure to act was “practically opening to the insurgents full liberty in this kingdom.” It was Adams’ concluding sentence, however, that probably got Russell’s attention: “It would be superfluous of me to point out to your Lordship that this means war.”

More irritated than intimidated, Russell nevertheless responded to Adams’ bluster on September 8, writing that “instructions have been sent which will prevent the departure of the two ironclad vessels at Liverpool.” Dudley’s dogged determination had finally borne fruit; the Laird rams would never threaten the Union Navy’s dominance of the seas. On October 10, Dudley reported to Seward “that the issuing of orders to Captain Inglefield satisfied me that they [the British authorities] were now in earnest….I think I can now say to you with every assurance of its truth that the two rams are stopped.” In May 1864, the British government bought the two ships, thus forever keeping them out of Confederate hands.

Dudley had no time to rest on his laurels. Bulloch had already begun shifting most of his shipbuilding projects to Scotland and France. Dudley and his agents followed close behind. In a February 17, 1864, letter to Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory, Bulloch complained that “the spies of the United States are numerous, active, and unscrupulous.” He concluded, “It is now settled beyond a doubt that no vessel constructed with a view to offensive warfare can be built and got out of England for the service of the Confederate States.” While some ships, such as Florida and Alabama, did inflict significant damage to the Union’s merchant fleet, no armored ironclads ever sailed for American waters.

The end of the war did not bring an end to Dudley’s work. He continued to gather evidence on Britain’s assistance to the Confederacy, confident there would eventually be a day of reckoning. That would come beginning in 1867. In demanding compensation for the damage done by the British-built commerce raiders, the United States argued that Britain had inadequately followed its neutrality laws—what became known as the “Alabama Claims.”

Dudley’s reports provided much of the evidence supporting the U.S. claims, but years of diplomatic wrangling ended in a stalemate. Then in 1871, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish negotiated the Treaty of Washington, calling for an arbitration panel to settle the dispute. In May 1871, the arbitrators met in Geneva and issued a report in September 1872 awarding the United States $15.5 million—closing the books on the war’s most successful intelligence network.

Dudley returned to his law practice in Camden, N.J. In April 1893, he died of a heart attack. For years, the local Grand Army of the Republic lodge placed a flag on his grave in recognition of his service to the Union. Of 324 ships built either as commerce raiders or to run the Union blockade, 126 were sunk.

Gordon Berg writes from Gaithersburg, Md.