Cruel irony of segregated dedication ceremony has given way to reverence and rallies

The brand-new Lincoln Memorial should have inspired a dedication ceremony of, by, and for the people—black as well as white. To adorn its interior, 72-year-old Yankee sculptor Daniel Chester French had created a magisterial but accessible colossus designed to beckon admirers of all backgrounds. And the inscription French had commissioned for the tablet behind the massive statue made no exceptions based on race:

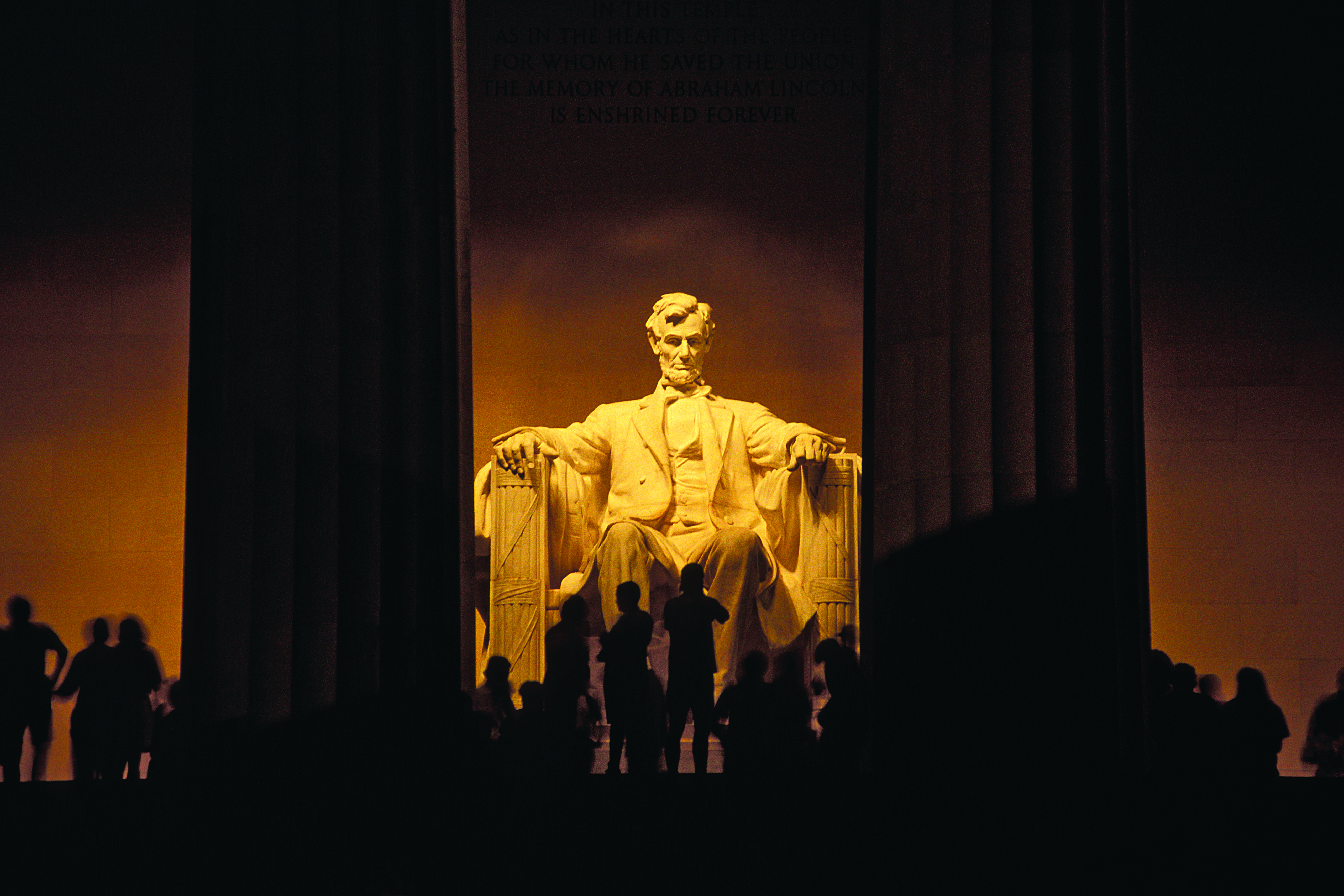

“In this temple / as in the hearts of the people / for whom he saved the Union /the memory of Abraham Lincoln / is enshrined forever.”

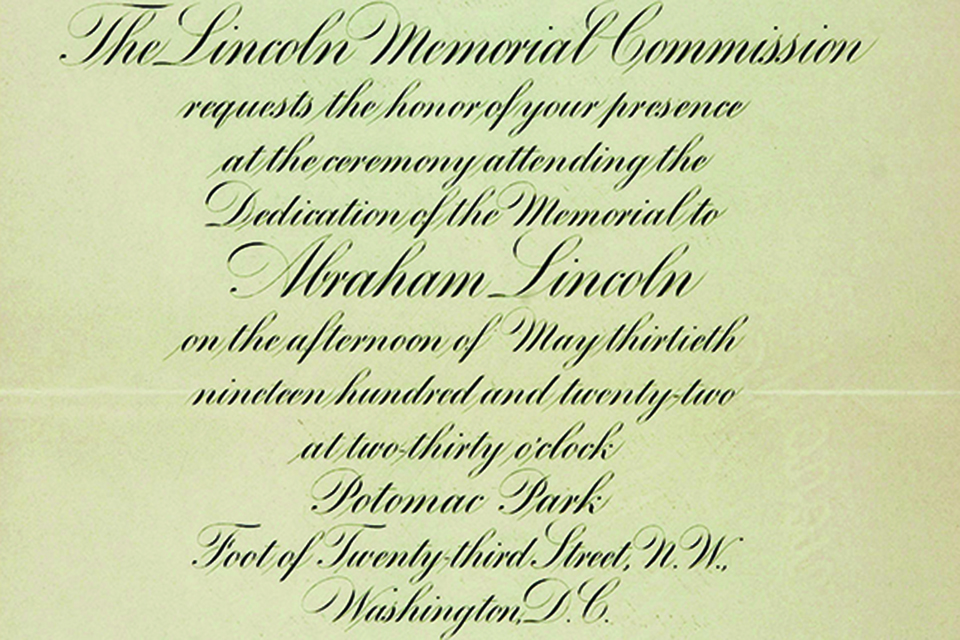

But the May 22, 1922, dedication, long a dream for Washington’s countless Abraham Lincoln admirers, instead turned into a nightmare for the citizens Lincoln had long been credited with helping the most.

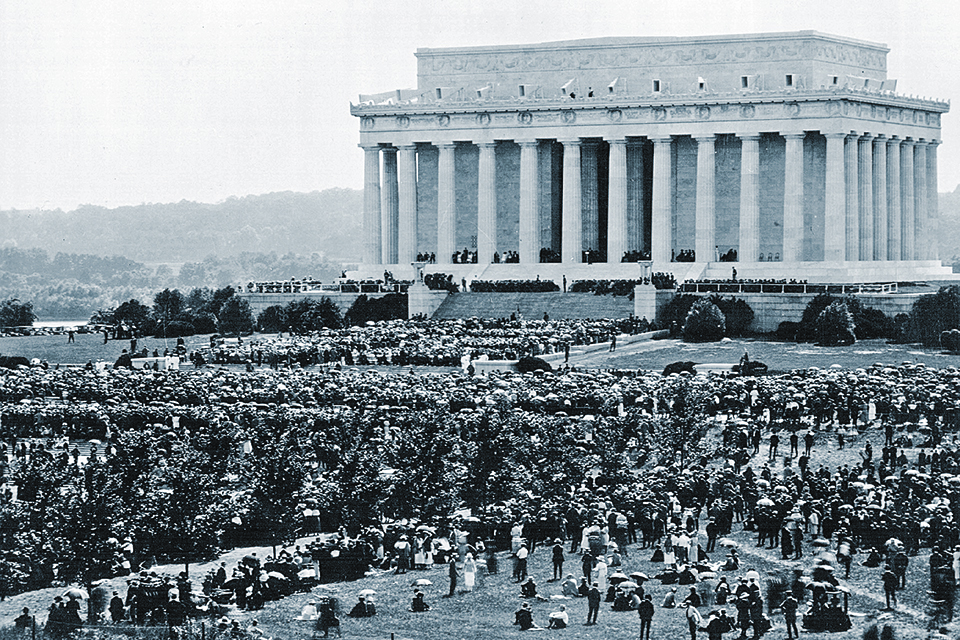

African Americans arrived at the Greek-style temple rising from Washington’s once-swampy West Potomac Park early that hot dedication day, hoping for places at the front of a throng that eventually swelled to 50,000. For them, Lincoln was still Father Abraham, the Great Emancipator. But before the pageant got under way, on instructions from the Southern-born superintendent of the Office of Public Buildings, soldiers armed with guns and bayonets rousted the early arrivals from their chairs and herded them into a “colored section” at the far edge of the grounds, “roped in from the rest of the audience.” Aggressive bullying, one white Marine corpsman boasted crudely at the scene, was “the only way you can handle these ‘n——s.’”

To add insult to injury, a group of “grey-clad survivors of the Confederate army”—elderly white men who had waged the rebellion to defy Lincoln and defend slavery—received special seats of honor alongside surviving veterans from the Union side. The Washington Post applauded the fact that “two groups of bowed men in blue and gray had seats to right and left of a flag for and against the existence of which they once did battle.” But an African-American eyewitness saw cruel irony in the fact that “Jim-Crowism of the grossest sort” had been practiced by “the hypocrites of the great nation” on a day devoted to Lincoln. The seating anomalies made it clear, he complained, that “the spoils have gone to the conquered, not the conquerors.”

That dedication day, yet another indignity awaited Lincoln’s African-American admirers. This additional slight, however, would at first be known only to a few of the special guests who ascended to the speakers’ platform atop the Lincoln Memorial steps—all of them as white as the pillars fronting the building. The only African-American speaker on that day’s program was Robert Russa Moton, principal of the all-black Tuskegee Institute. In a seemingly generous gesture, organizers had invited him to represent “the colored race” with a separate, and presumably equal, dedication speech. Though known as a conservative, Moton drafted a surprisingly provocative address, insisting: “So long as any group within our nation is denied the full protection of the law,” then what Lincoln had called his “unfinished work” would remain “still unfinished,” and the new Memorial itself, “but a hollow mockery.”

After reviewing Moton’s manuscript in advance, however, the White House insisted that the critical remarks be expunged; Moton could either intone a more anodyne speech or forfeit his place on the program. Facing the prospect of losing the largest audience he had ever addressed, Moton gave in to the censors. His original manuscript would remain unpublished for decades.

Following Moton’s truncated speech, Chief Justice William Howard Taft, chairman of the Lincoln Memorial Commission, rose to declare almost defiantly that the new shrine represented the “restoration of brotherly love of the two sections,” not the two races. Lincoln, he insisted, was “as dear to the hearts of the South as to those of the North.”

In his own remarks, President Warren G. Harding seconded that emotion. As if speaking mainly to the Confederate veterans in the audience, Harding declared of Lincoln: “How it would soften his anguish to know that the South long since came to realize that a vain assassin robbed it of its most sincere and potent friend…[whose] sympathy and understanding would have helped heal the wounds and hide the scars and speed the restoration.” To the black newspaper the Chicago Defender, Harding’s words seemed “a supine and abject attempt to justify in palavering words of apology the greatest act of the greatest American—the freeing of the poor, helpless bondmen.” The paper went so far as to advise its readers that no Lincoln Memorial dedication had occurred at all that day.

In view of its disgraceful unveiling, the most remarkable thing about the Lincoln Memorial may be that it eventually emerged as the most universally revered of America’s secular shrines—and the most unifying.

Nearly a century later, it is now the first and most important stop on many Americans’ list of patriotic destinations, as well as a magnet for groups numbering in the tens of thousands. Here, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. capped the 1963 March on Washington with his “I Have a Dream” speech. Here, a beleaguered Richard Nixon famously appeared unannounced shortly before his resignation to commune with Lincoln’s spirit. And here, presidents-to-be from Bill Clinton to Donald Trump have appeared on the eves of their inaugurations to lay symbolic claim to Lincoln’s mantle. Whether serving as a shrine for contemplation or a rallying spot for protest or pageantry, the memorial seldom disappoints.

Not unimportant, the memorial is the crowning achievement of the gifted but elusive man who created the statue that looms within its walls: sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850-1931). Thanks to his vision and talent, the site still evokes the combination of majesty and humility that Americans believe their country and their greatest leaders personify. The somber behemoth manages to present its subject, as French put it, in all “his simplicity, his grandeur, and his power”—no easy trinity of virtues to convey in a single work of art. The textured portrayal personifies Americans’ concurrent belief in both their collective modesty and their preeminent standing in the world.

French’s marble statue of Lincoln is probably the most famous sculpture ever created of or by an individual American—not to mention, at 19 feet in height and some 200 tons in weight, the largest. It is the most frequently visited, the most widely cherished, and the most often reproduced (in miniature and selfie alike) of national icons. In an age in which controversy rages over public statuary honoring Confederate generals, slave-holding founding fathers, and other blemished figures from the American past, French’s Lincoln remains majestically enthroned without objection.

That this inspiring statue was the work of a reserved, sometimes impenetrable, professional artist who lived most of his life in the Gilded Age and left few written clues about his ideas or instincts, makes its ever-expanding relevance all the more astonishing. A professional sculptor for nearly half a century when his most famous statue took its place among Washington’s great public monuments, “Dan” French was on the most obvious level a crusty New Englander, a man of many accomplishments but few words. His shut-mouthed exterior, however, masked the soul of a creative genius.

French never illuminated his art through explanation. Rather, he spoke, indeed existed, through his art—expressing himself passionately through an uncommon skill and a common touch that no other American sculptor has ever so successfully combined. “If I’m articulate at all,” he once remarked with typically modest understatement, “it is in my images.” Judged on visual terms alone, French became America’s most articulate public artist. He created the iconic “Minute Man” for his home town, Concord, Mass., when he was only 24 years old. He went on to fashion the central symbol of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, “The Republic,” along with acclaimed, realistic portraits of Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Adams. He specialized in campus statuary like “John Harvard,” “Thomas Gallaudet,” and “Alma Mater” at Columbia, along with evocative, symbol-laden cemetery markers honoring the late sculptor Martin Milmore in Boston and the three Concord-born Melvin brothers who died during the Civil War.

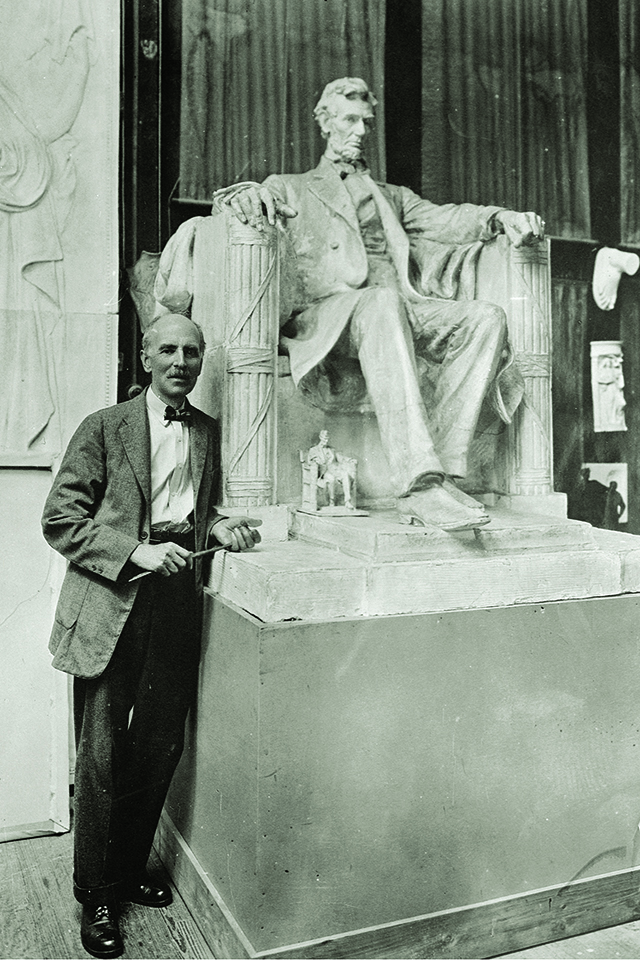

Wartime military heroes became a specialty as well—all of them, of course, Union men. By the time French earned the commission to create the Lincoln Memorial statue (seemingly without competition), he was already America’s best-known, highest-paid sculptor, a trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a summer resident of Stockbridge, Mass., where he lived and worked at a magnificent estate and studio, “Chesterwood”—now a National Trust site (see sidebar, below). French also chaired the National Commission of Fine Arts—the very body assigned to approve the Lincoln Memorial. He stepped down reluctantly only when it became evident the conflict of interest was insurmountable.

Even so, the project might easily have gone off the rails. For one thing, congressional backers did not all believe that the swampy park at the western edge of the new National Mall was a fitting and proper spot for a Lincoln Memorial. Alternative suggestions included Union Station, the Capitol, the National Observatory, the Soldiers’ Home, and the midpoint between Washington and the Confederate capital of Richmond.

Even when wiser heads prevailed regarding the site, details about the statue itself remained in dispute. To save time and money, some proposed ordering a replica of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ “Standing Lincoln” in Chicago. It took a concerted effort by French and the Memorial architect, his frequent collaborator Henry Bacon, to block that effort.

Yet French originally contemplated a standing Lincoln of his own. He rejected the idea only when he wisely calculated that visitors approaching it from the bottom steps outside would be unable to see the face of an upright statue. For a time, French toyed with the idea of casting his Lincoln in bronze, an idea he later rejected.

Planners chose the words of the Gettysburg Address and First Inaugural to surround the statue, but had French gotten his way, Lincoln’s farewell address to the people of Springfield, Ill., delivered on February 11, 1861, when he left for Washington, D.C., and his remarkable consolation letter to Lydia Parker Bixby, a Boston woman who lost five sons in battle, would have been added—the first an acknowledged masterpiece, though it antedated the Civil War; the latter a work whose authorship has since come under question. Less turned out to be more. As if by magic, French produced a small clay model at Chesterwood that captured the essence of the future statue from the start.

Not until the building was nearing completion did the sculptor realize that the envisioned 12-foot-high final work would be dwarfed within its vast atrium. The sculptor convinced Congress to pay to increase its height by seven feet only after stringing a proportionately sized plaster head from the ceiling of the memorial’s interior to demonstrate that anything smaller would look underwhelming. French’s Italian-born, Bronx, N.Y., carvers then crafted the final statue from 28 blocks of marble. Remarkably, it was never assembled into a whole until it arrived at the building, block by block, in 1919.

The final result represented French’s last stand for classicism in the fast-approaching age of modernism. That his Lincoln Memorial has so defiantly transcended changing artistic tastes and shifting public moods is a testament to the artist’s almost defiant belief in the enduring relevance of the heroic image. With the Lincoln Memorial, French accomplished not only a magisterial portrait for posterity, but also a platform for its infinite aspirations.

But the metamorphosis of the Lincoln Memorial into something greater than a memorial to Lincoln did not commence until 1939, 17 years later. That spring, African-American contralto Marian Anderson was blocked from performing at the Washington headquarters of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Resigning her DAR membership in protest, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt urged that the concert be relocated to an even larger stage: the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. There, Anderson’s hour-long Easter Sunday program attracted an integrated crowd of 75,000, “the largest assemblage Washington has seen since Charles A. Lindbergh came back from Paris,” said the New York Herald-Tribune. A national radio broadcast brought to millions more Anderson’s magnificent renditions of “My Country ’Tis of Thee” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

The meaning of the Lincoln Memorial would never be the same; it had been transfigured, in the course of a single hour, from a monument to sectional reunion into a touchstone for racial reconciliation. The prestige of the Memorial expanded further through the power of popular culture. Frank Capra’s film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, released just six months after the Anderson concert, featured a particularly evocative scene from its interior. In search of inspiration, the uncertain freshman “Senator Jefferson Smith,” in the person of Lincolnesque actor James Stewart, visits the Memorial and listens “dewy-eyed” as a little boy reads the Gettysburg Address aloud to his visually impaired grandfather. An elderly black man enters the chamber just as the words “new birth of freedom” escape from the child’s lips.

The scene fades out with a giant close-up of the statue’s face to the swelling strains of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “The Star Spangled Banner.” Dr. King’s appearance a quarter century later, in what he called “the symbolic shadow” of “a great American,” only cemented the metamorphosis.

The original, flawed 1922 Lincoln Memorial dedication closed with a benediction—after which most of the dignitaries along its top step clustered around white-bearded Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s sole surviving son, to offer greetings. As the huge, segregated crowd below began to disperse, French strolled unnoticed into the building and spent a few silent minutes communing with the huge marble figure he had created. After a few moments in solitude, he glanced to his side and noticed Robert Russa Moton standing next to him, gazing at the work as well.

To French’s delight, Dr. Moton “praised the statue.” French, in turn, confided to him that he remained worried about the way it was lit, for despite last-minute modifications, the sculpture still did not look as he had intended. “Dr. Moton was a sympathetic listener and Dan found himself being drawn out to give him some of the details of the building,” remembered the sculptor’s daughter.

Did French confide to Moton that he had intended that the statue would “convey the mental and physical strength of the great president”? Did Moton confide his disappointment at the prejudice manifested at the dedication ceremony? Unfortunately, no one made a further record of their conversation.

We know only that after they spoke, “the powerfully built college president and the frail-looking sculptor walked out into the sunshine and the May wind as they went down the steps and stood on one of the terraces looking up at the memorial”—the same breathtaking view enjoyed by millions of fellow Americans, black and white, ever since.

Harold Holzer, winner of the Lincoln Prize and chairman of the Lincoln Forum, is the author, coauthor, or editor of 53 books, most recently Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French, from which this article is adapted.

The House at Monument Mountain

In 1896, longing for a place to live and work during the summertime, Daniel Chester French purchased a farmhouse in Stockbridge, Mass. Although the main structure was dilapidated and an old barn seemed unsuitable as a studio, the surrounding vistas captivated him: Monument Mountain rising in the near distance, and a carpet of trees and flowers blooming on all sides. French called it “the best ‘dry view’ he had ever seen.” Obtaining a cash advance on a statue he was fashioning of General Ulysses S. Grant, French paid $3,000 to acquire both buildings and 150 surrounding acres. He named his new estate “Chesterwood” after his grandparents’ hometown of Chester, N.H.

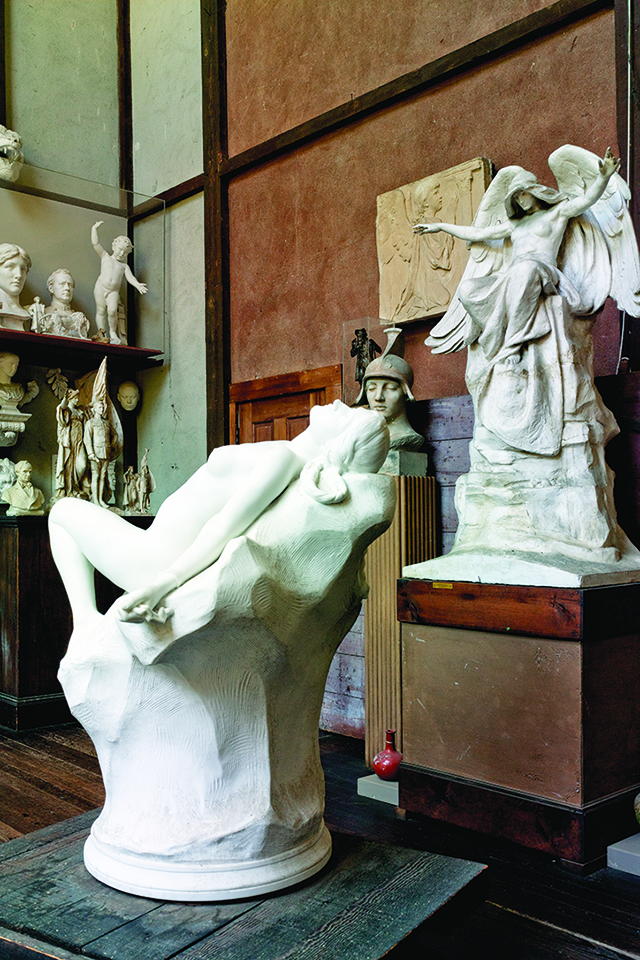

For the next 33 years, French and his family summered here. The sculptor hired architect Henry Bacon—future designer of the Lincoln Memorial—to create a fine replacement house and an adjacent studio (moving the barn up the hill). By 1898, French began working here on an equestrian statue of George Washington for the city of Paris. Here, French would later fashion the original clay model of his seated Lincoln, plus sculptures of Civil War Generals Joseph Hooker and Charles Devens. French later said of his Chesterwood routine, “I spend six months of the year up there. That is heaven; New York is—well, New York.”

Today the house, still furnished as French decorated it, and studio, housing his original plaster models and undisturbed workplace—now National Trust for Historic Preservation sites—are open to the public seven days a week, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., from May 25 through October 27. A bonus is a gallery devoted to French’s small plaster models and statuettes. Admission: $20 adults, $10 children 13-18; under 13 free, with discounts for seniors and veterans. For information: www.chesterwood.org.