Wounded and Weeping

When Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee hit bookstores in 1970, I had just ventured from northeastern Ohio to Albuquerque, New Mexico, a young man almost ready to start college. Part of the reason I went that direction was my love for Western lore, having grown up with TV Westerns, Hollywood oaters, Zane Grey novels and at least one unforgettable Custer’s Last Stand painting. By the early 1970s antiestablishment views were running rampant on college campuses, and a full-fledged cultural rebellion was under way. Barely on the fringe of the “movement,” I did question traditional beliefs, but mostly to myself. I undoubtedly was more history-minded than most, and doubts about Manifest Destiny and the way the 19th-century “establishment” had treated Indians (thank you, Broken Arrow and a few Gunsmoke episodes) had begun to rise if not surface in my overloaded head. Regardless, I was more focused on my own destiny in the modern West and how to sneak photos of Taos Pueblo without paying residents for the privilege.

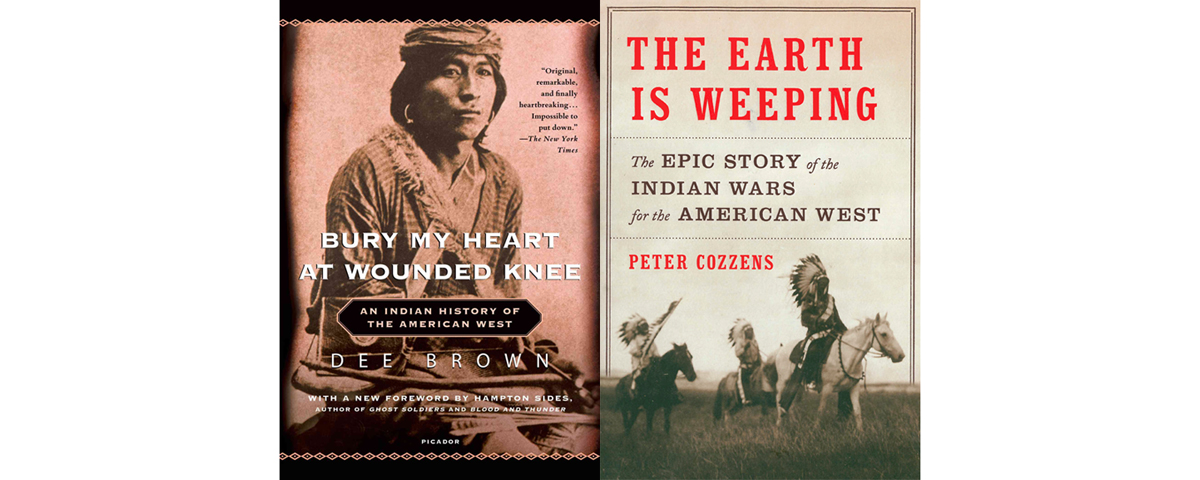

Then I stumbled across Brown’s book—an eye-opener for me and, as I would later learn, thousands of other readers. We had never seen anything like it—a historical account of U.S. expansionism told from the Indian perspective by a white man whose great-grandfather reportedly had rubbed elbows with David Crockett. For 47 years Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee has greatly influenced readers’ perceptions of the Indian wars and the “conquest” of the West. In our June 2017 Interview, author Peter Cozzens recalled reading and enjoying the book while in high school. He came to respect Brown (who died in 2002 at age 94) for having presented a narrative “that ran counter to the tide of many decades of academic and popular work.” But, Cozzens adds, “In trying to correct the vast record of injustice done the American Indians, [Brown] went too far in the other direction…[and] made no attempt at historical balance.” Cozzens’ desire to restore such balance was his motivation for writing the 2016 book The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West. Drawing on a wealth of Indian primary sources and the recollections of white participants, he addresses many of the misconceptions and myths surrounding the Indian wars.

In the August 2017 cover article, “Truths About the Frontier Army,” Cozzens zeroes in on one of those myths—that generals and other officers who served out West were inherently antagonistic toward Indians. The frontier officer corps, he contends, earned a reputation as “unfeeling exterminationists” due to isolated comments made by the likes of Lt. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman (“We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children”) and Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan (particularly a disputed comment remembered today as “the only good Indian is a dead Indian”). But Cozzens makes a strong case that the Army was not hell-bent on killing Indians, and that neither Sherman nor Sheridan sought the literal extermination of Indians. Generals such as John Pope and Alfred Terry, Cozzens writes, expressed concern over the plight of the Indians, harboring views “more enlightened and nearly always more pragmatic than those of Indian-rights advocates.” He also stresses that aside from how the officers or their men felt about Indians, the Regular Army was ill-prepared for frontier service.

Now that I think about it, many of the old small- and big-screen Westerns depicted despicable Army officers who were practically psychopathic in their wish to wage total war and exterminate savages. Such bluecoat stereotypes often appeared on-screen right alongside the requisite whooping, bloodthirsty warriors circling wagon trains and small Army detachments. Striving for balance in history or most anything else seems a noble undertaking. Wounded and weeping are both effective words to describe the real-life tragedies of the Indian wars. WW

Wild West editor Gregory Lalire wrote the 2014 historical novel Captured: From the Frontier Diary of Infant Danny Duly. His article about baseball in the frontier West won a 2015 Stirrup Award for best article in Roundup, the membership magazine of Western Writers of America.