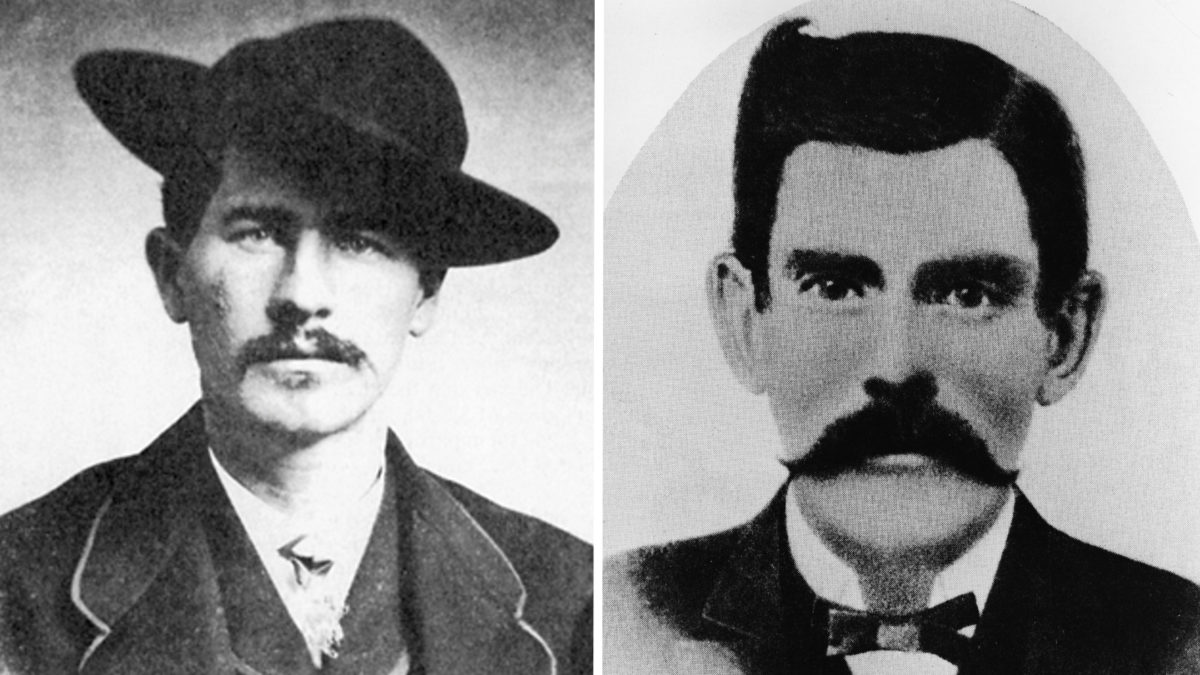

Values associated with friendship, whether on the frontier or not, include understanding, support, honesty, sympathy, empathy, affection, trust and positive reciprocity, such as buying each other drinks at the local saloon. Keep these timeless values in mind while checking out the reader-friendly cover story on Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, written by Holliday biographer Gary L. Roberts. Then judge for yourself how their frontier friendship rates on a scale of 1 (epitomized by the dubious, jealousy-ridden relationship between Texas outlaws turned prisoners John Wesley Hardin and Bill Longley) to 10 (consider the mighty Wild Bunch bond between Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid that could not be weakened by either a move to South America or cohabitating with only one woman, Etta Place).

Actually, some rejudging of the Holliday-Earp relationship might be in order if you have formed an opinion based on their interactions in any number of movies, including Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (Burt Lancaster as Wyatt, Kirk Douglas as Doc) and Tombstone (Kurt Russell as Wyatt, Val Kilmer as Doc). For instance, as Roberts points out, while the real Holliday could be a mean drunk and possessed some nasty habits, he had—contrary to his screen image—more friends in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, and beyond than just Earp. The same support Doc showed Wyatt more than a few times, he also gave to other friends from Dodge City, Kan., and elsewhere, and when Holliday was dying of tuberculosis in Glenwood Springs, Colo., several people (none named Wyatt) cared enough about him to pay for his funeral. According to Roberts, a local paper reported that Doc died “in the presence of many friends.”

Not that Hollywood has distorted their friendship beyond recognition. On the big screen the entertaining pair seem a total contrast—Earp the tall, stalwart lawman, Holliday the sickly, sometimes charming scoundrel—and indeed they really were different in many ways. But like Holliday, Earp’s primary profession was gambling, and Doc (though the movies often hide this point) did not side with the law only to back up friend Wyatt. Roberts notes that even Bat Masterson, who wrote many good things about Wyatt but not about Doc, said of Holliday in 1886, “When I was sheriff in Dodge City, I got to know him very well, and there wasn’t a man in the whole place whom I would call on more quickly to uphold the law than Doc Holliday.”

That “bad” Holliday and “good” Earp could actually be friends is often regarded as a mystery. But those are just labels. Like most of us, these two prominent Western characters should be fitted for gray hats instead of white or black ones. What bound Holliday and Earp together, says Roberts, were honor, courage and loyalty. Arguably more valued on the frontier than today, those traits even surfaced in some outlaw hideouts—though they were not prerequisites for the formation of certain friendships, say those created in bucket-of-blood saloons.

Often a frontier fella’s best friends and supporters were family—moms, dads, sisters and especially brothers. Just look at the Daltons, Youngers, Mastersons, Marlows and, yes, the Earps. That the Earp brothers often stuck together, including three of them (Wyatt, Virgil, Morgan) in the 1881 Tombstone fight, is something nobody questions, even if none of the Earps wrote about their feelings (loving or otherwise) toward each other. Doc and Wyatt didn’t write about their feelings either, but they weren’t blood relations, which makes people wonder how they could be so mutually devoted. Their unlikely connection displeased some people, then and now. But for some of us the Earp-Holliday relationship is the most interesting part of the Tombstone story. Such friendships are hard to find in any age. And as Wyatt supposedly told biographer Stuart N. Lake, “In the old days neither Doc nor I bothered to make explanations.”