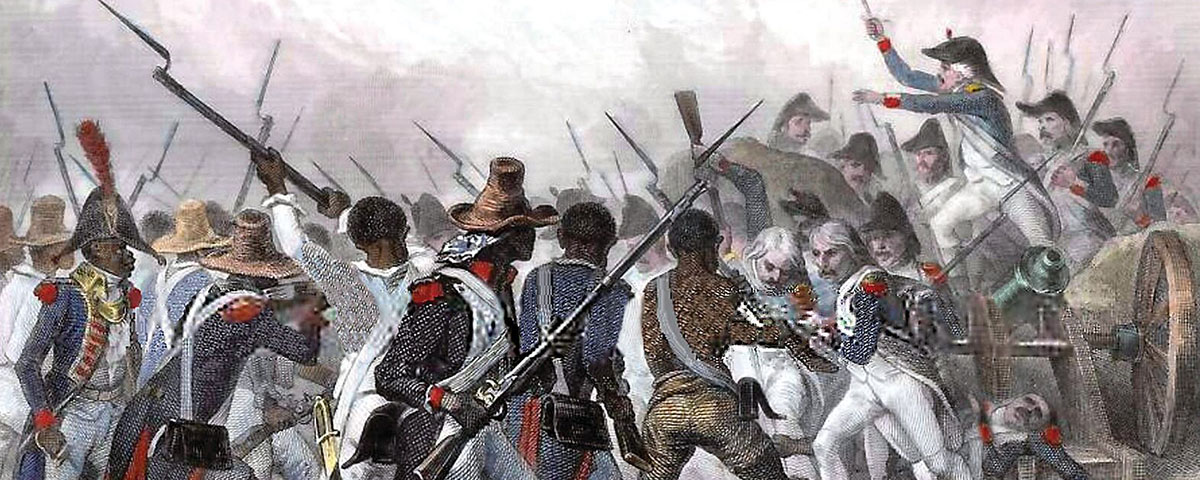

Surprisingly, the drums signaling for a cease-fire from the French bastion at Vertières penetrated the chaos of battle on the Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue. General Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau, had just witnessed a brilliant attack orchestrated by a rebel commander, and he wished to pay proper homage. As the guns fell silent, a French staff officer rode forward and shouted, “General Rochambeau sends compliments to the general who has just covered himself with such glory!” Message delivered, the killing resumed.

By midafternoon on that bizarre day in November 1803, following a final, feeble French counterattack, Rochambeau abandoned his positions and retreated to the coast. The next morning envoys finalized the terms of capitulation, and Saint-Domingue was in rebel hands. On New Year’s Day 1804 the victors renamed their new nation Haiti.

Occupying the western third of the island of Hispaniola, Saint-Domingue was the richest of France’s colonies. Initially a Spanish holding, it was ceded to France in 1697 and soon became the greatest source of agricultural wealth in the West Indies. The wealth sprang from immense sugar and coffee plantations, which exploited imported African slave labor. By 1797 there were more than a half-million slaves in the colony, ruled over by a white colonial population numbering scarcely 30,000. Harsh conditions prompted violent uprisings, and a full-fledged slave revolt broke out in August 1791. For the next dozen years Saint-Domingue became a charnel house, as England, Spain, French royalists, French republicans and former slaves all joined in, forming shifting alliances for wildly divergent objectives.

In 1794 the French First Republic abolished slavery in all of its colonies, and by century’s end Saint-Domingue was largely under the control of General François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, a native-born former slave. In 1801 Louverture, who had helped drive off both the English and Spanish, pushed for independence. In response Napoléon Bonaparte dispatched more than 20,000 troops to restore French rule. The move prompted rebel massacres of colonists. Napoléon’s troops soon re-established order. But when colonial authorities shipped Louverture to France in chains and reinstituted slavery on nearby Guadeloupe, the simmering rebellion burst into flames.

The French poured additional forces into the colony, but disease, mass defections of black troops and rebel resistance took a toll. Britain and France renewed hostilities in early1803, and a British fleet established naval superiority off Saint-Domingue. The remaining French force was soon penned in along the northern coast. After withdrawing from Vertières on November 18, Rochambeau negotiated surrender to the blockading British naval force.

A new nation was born. Yet for two centuries Haiti—plagued by political instability, economic malaise and recurring natural disasters—has struggled to overcome the trauma of its birth.

Lessons:

Don’t refight the last war. The French expeditionary force comprised veteran formations, but they were unprepared for the climate, terrain and enemy they faced in Haiti.

Hope is a combat multiplier. For years the rebels suffered humiliation and defeat at the hands of their colonial masters, but they never surrendered their desire for freedom.

Successful revolutions don’t guarantee successful nations. After conducting history’s largest and most successful slave revolt, the rebels secured their long-sought independence. But political instability has since crippled Haiti for most of its sad and torturous history.