The 6-pound round of Confederate solid shot rolled into the fire and exploded. Shrapnel flew throughout the room full of Federal soldiers. Miraculously, no one was killed. A few men incurred minor injuries, and one, Private Harry Chait of Detroit, received burns serious enough to require him to spend several days at Camp Davis Hospital.

Not an uncommon occurrence during the Civil War. But this incident took place on a chilly winter’s night in 1942—and Private Chait didn’t wear Union blue but the olive drab of the 1st Battalion, 244th Coast Artillery.

The story behind this most unlikely incident takes place at Fort Macon, N.C., and it begins on December 7, 1941, when America entered World War II. Part of hurriedly preparing the nation for war included establishing a line of air and sea defenses along both coasts. This put Fort Macon on a war footing for the first time in 80 years.

The brick and masonry fort was originally built in 1834 to protect Beaufort Inlet and the city of Beaufort, North Carolina’s only major ocean deep-water port. It was one of 38 permanent forts known as the Third System. Designed by Brig. Gen. Simon Bernard of the Army Corps of Engineers in the traditional pentagon configuration, it was only intermittently garrisoned until the outbreak of the Civil War. Captain Robert E. Lee gave the fort a thorough inspection in 1840.

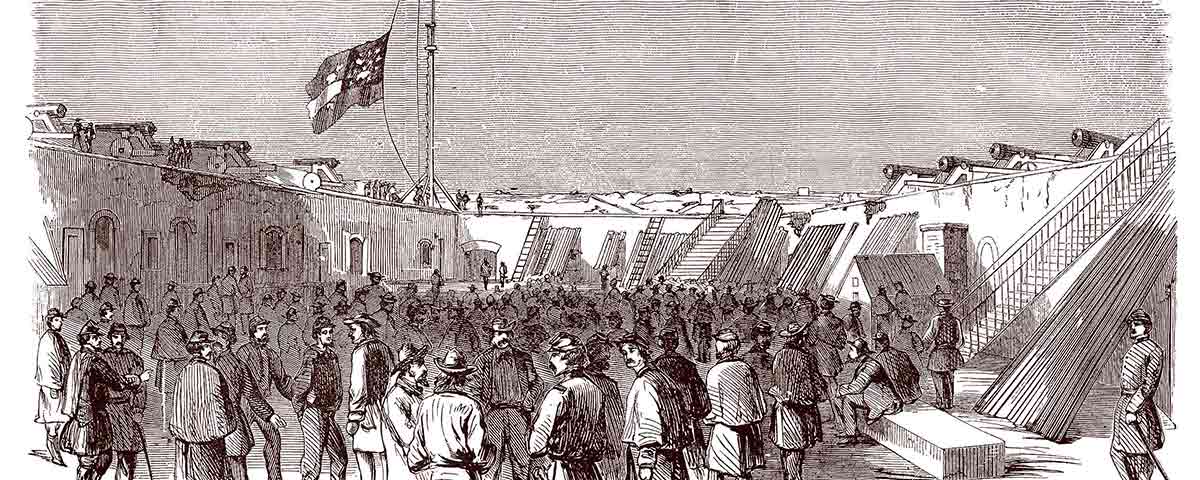

Two days after the fall of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, North Carolina militia forces seized the practically unmanned installation and armed it with 54 heavy cannon. After the city of New Bern, N.C., fell to Union forces on March 4, 1862, a contingent of troops under Brig. Gen. John G. Parke captured nearby Morehead City and Beaufort without resistance. Parke then landed on Bogue Banks and invested Fort Macon. On April 25, Union forces, aided by four Federal warships and floating batteries, bombarded Colonel Moses J. White (West Point, Class of 1858) and his 400 North Carolina troopers for 11 hours. The fort’s masonry ramparts suffered extensive damage from the Union’s rifled cannons, and White surrendered the fort the next day. It would remain in Union hands for the rest of the war and through Reconstruction.

Fort Macon was officially decommissioned in 1877. State troops occupied it briefly during the Spanish-American War. The Army again abandoned the fort in 1903, and it was offered for sale as military surplus in 1923. But an act of Congress ceded the fort and surrounding acres to North Carolina for a state park. The Civilian Conservation Corps restored the masonry walls and interior buildings. The addition of recreational facilities allowed Fort Macon to open as North Carolina’s first official state park on May 1, 1936. It remained under state control until the afternoon of December 19, 1941, when Lt. Col. Henry G. Fowler and three other officers knocked on the door of Mrs. Virginia G. Humphrey, the park’s caretaker, and informed her that the U.S. Army intended to take over the fort for use as a coastal defense installation.

Men of the 244th Coast Artillery, formerly a New York National Guard unit, soon arrived followed by their 155mm “Long Tom” guns. Two gun batteries and a 500-man administrative Headquarters Battery brought the fort’s contingent to nearly 900 men and eight big guns. The guns were test-fired on December 24 and life soon entered into the monotonous routine of garrison duty. That routine was soon disrupted.

Some of the enlisted men were billeted in the same quarters occupied by their Civil War counterparts. Each room had a working fireplace and a chilly evening encouraged the occupants of Casemate 2 to lay a warming fire. Someone thought that two old cannon balls found near the fort would make good andirons. One of them did. The other one exploded in the fire, setting bedding ablaze, blowing one man out the door, and sending Private Henry Chait to the hospital. When the incident was reported in the local newspapers, they humorously characterized it as two more Yankees gotten by a Confederate cannon ball.

After nine months, the men of the 244th were sent to the South Pacific. The Army stayed at Fort Macon until 1946 when it reverted back to the state. Henry Chait remained the only soldier there wounded by “enemy” fire.

While You Visit

Fort Macon State Park:

Fort Macon is part of a 720-acre state park featuring a museum-quality coastal education center and an unspoiled shoreline for swimming, surf fishing, and leisurely beachcombing.

Nearby New Bern:

Nearby New Bern was the Colonial capital of North Carolina and is sister city to Bern, Switzerland. In addition to a tree-shrouded neighborhood of Colonial-era homes, restored Tryon Palace, home of the last Colonial governor, is open for guided tours. The New Bern Battlefield (March 14, 1862) features some of the best-preserved Civil War earthworks still in existence. Tours can be arranged.

Havelock N.C.:

Havelock, halfway between New Bern and Fort Macon, is the site of Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, home of the Harriers. The Tourist and Event Center features the East Carolina Aviation Exhibit celebrating the heritage of Marine Corps’ aviation through a variety of historic exhibits, artifacts, and programs. A number of aircraft can be viewed up close around the exhibit grounds.

Crystal Coast:

Adjacent to Fort Macon is the Crystal Coast, an 85-mile barrier island featuring numerous resort accommodations and some of North Carolina’s finest beaches and fishing sites. It is also home to the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knolls Shores, which is open year-round.

Beaufort, N.C.:

A short drive away is Beaufort, N.C., on Bogue Sound. There are boat tours to Shackeford Island, and the Beaufort Historic Site Visitors Center and Museum and the North Carolina Maritime Museum are worth exploring.