Just after 1 p.m. on Jan. 15, 2006, a convoy carrying members of the Canadian Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) entered Kandahar through its twin gates, known—with a tongue-in-cheek nod to McDonald’s—as the “Golden Arches.” The five vehicles passed a checkpoint, slowed to negotiate a traffic circle, then picked up speed. They were minutes from the relative safety of Camp Nathan Smith, PRT’s base in Afghanistan’s restive southern province.

As the convoy passed a taxi stand, a silver Toyota minivan swung out alongside the unarmored Mercedes-Benz G-Wagon light utility vehicle carrying veteran Canadian diplomat Glyn Berry. A moment later the Toyota exploded, hurling Berry’s vehicle into the air. The G-Wagon rotated several times before crashing back to earth, landing on its side in a tangle of flaming wreckage. Three soldiers lay wounded. Berry was dead. Canada had suffered its first fatality of what would become a blood-soaked year.

Canadian military personnel first deployed to Afghanistan in late 2001, and over the next four years eight soldiers were killed—the first four in a friendly fire incident involving an American F-16. Overall casualties were remarkably light, considering the Canadians’ extensive operations in eastern Afghanistan, primarily in Paktika Province.

In the spring of 2005 Defense Minister Bill Graham announced in Parliament that Canada would move its military operations into Kandahar province, the birthplace and heartland of the Taliban insurgency. The move south would drop Canadian forces into the Afghan equivalent of the Wild West and ultimately engage them in the First and Second Battles of Panjwai. Fought in the first half of September 2006, the latter marked NATO’s most significant combat operation to date.

Gen. Rick Hillier, Chief of the Defense Staff, tapped the 1st Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (1 PPCLI), to form the core of Task Force Orion. On August 3 the unit fought the largest engagement of its tour. Ground zero was a white schoolhouse in a compound named Bayanzi, on the north side of the Arghandab River opposite Panjwai. The “Princess Pats” lost four men killed and 11 wounded. Six days later 1 PPCLI was replaced by a battle group built around the 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment (1 RCR), led by Lt. Col. Omer Lavoie. On August 22 a suicide bomber killed Corporal David Braun of 2 RCR. Such was the unit’s introduction to Kandahar.

The RCR troops were mounted aboard LAV III infantry fighting vehicles. The eight-wheeled LAVs were fitted with a two-man turret, armed with the M242 Bushmaster 25 mm chain gun and a coaxial 7.62 mm machine gun, with a 5.56 mm machine gun atop the turret. The vehicle could transport up to seven infantrymen, and its three-man crew could offer substantial fire support once its passengers had dismounted. The troops also used the G-Wagon, for scouting and liaison duties, and could call on a battery of newly acquired M777 155 mm howitzers and a troop of LAV II Coyote reconnaissance vehicles.

The new battle group took time to assess the terrain and the Taliban, eventually settling on an operation, code-named Medusa, to commence on September 2. The principal responsibility fell on the RCR’s Bravo and Charles companies. Charles would occupy Ma’sum Ghar, the high ground southwest of Panjwai, while Bravo moved into a blocking position a few miles north of the Arghandab, a dry wadi. American, NATO and Afghan forces would cover the eastern and western flanks. Charles would then push north to the banks of the Arghandab, but no farther. The wadi was the bomb line. The plan, Lt. Col. Lavoie later explained, was “to engage the enemy for the next three days with primarily offensive air support, as well as artillery and direct fire…before we actually committed the main force to the attack.” Then and only then, Charles would push north across the wadi into the heart of the Taliban fortifications. The operational plan was hardly revolutionary, but it maximized NATO assets and advantages.

Unfortunately, Operation Medusa fell apart, or more properly was dismantled, within hours. Derailed, then bedeviled by bad luck, it foretold of a coming train wreck.

As the Canadians dug in on Ma’sum Ghar on September 2, a horrific accident befell the British contingent. An RAF Hawker Siddeley Nimrod MR2 electronic reconnaissance plane monitoring the battle caught fire inflight and crashed 10 miles outside Kandahar, killing all 14 aboard. It was the worst single-day loss of life suffered by the British military since the 1982 Falklands War.

The next morning Charles Company moved down from Ma’sum Ghar into the hamlet of Panjwai, on the south bank of the Arghandab. The dam upriver had been destroyed, returning the river to its ancient rhythm of seasonal flooding and drying. While armored bulldozers started gouging out access lanes for the LAVs, Charles Company commander Maj. Matthew Sprague made a quick transit of the floodplain. Across the wadi lay the hamlet of Bayanzi, a known Taliban strongpoint, centered on the schoolhouse where the Princess Pats had been bitten.

Returning to the forward company group at Ma’sum Ghar, Sprague was visited by his superior, Canadian Brig. Gen. David Fraser, commander of the Multinational Brigade (MNB) for Regional Command South. At the same time the RCRs took over from the Princess Pats, the United States was handing off to the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). It was a historic moment, the biggest show in NATO’s history.

Fraser and Lavoie must have realized the reputation of the Canadian army was on the line. Medusa was a predominantly Canadian operation, overseen at the NATO level by yet another Canadian and waged on a battlefield the Canadians had fought over during their previous rotation. The pressure was on for fast and positive results.

Lavoie was shocked by the outcome of his parley with Fraser. The general ordered an immediate assault across the Arghandab into Bayanzi, targeting “Objective Rugby,” the white schoolhouse. Despite the fire plan, Fraser ordered Lavoie to push the security platoon across the wadi and have the men dig in, which they did. When Lavoie again objected to their exposure, Fraser promptly relented, ordering them back as night fell.

Then, in the middle of the night, Fraser abruptly ordered Lavoie to mount a full-blown assault at dawn. NATO’s overwhelming, indeed absolute, superiority in artillery and air assets would not be brought to bear as planned. Charles Company would have support during the assault, but those “three days with primarily offensive air support, as well as artillery and direct fire” had vanished. On the fly Fraser had dropped three days of preparation in favor of what was essentially a cavalry charge.

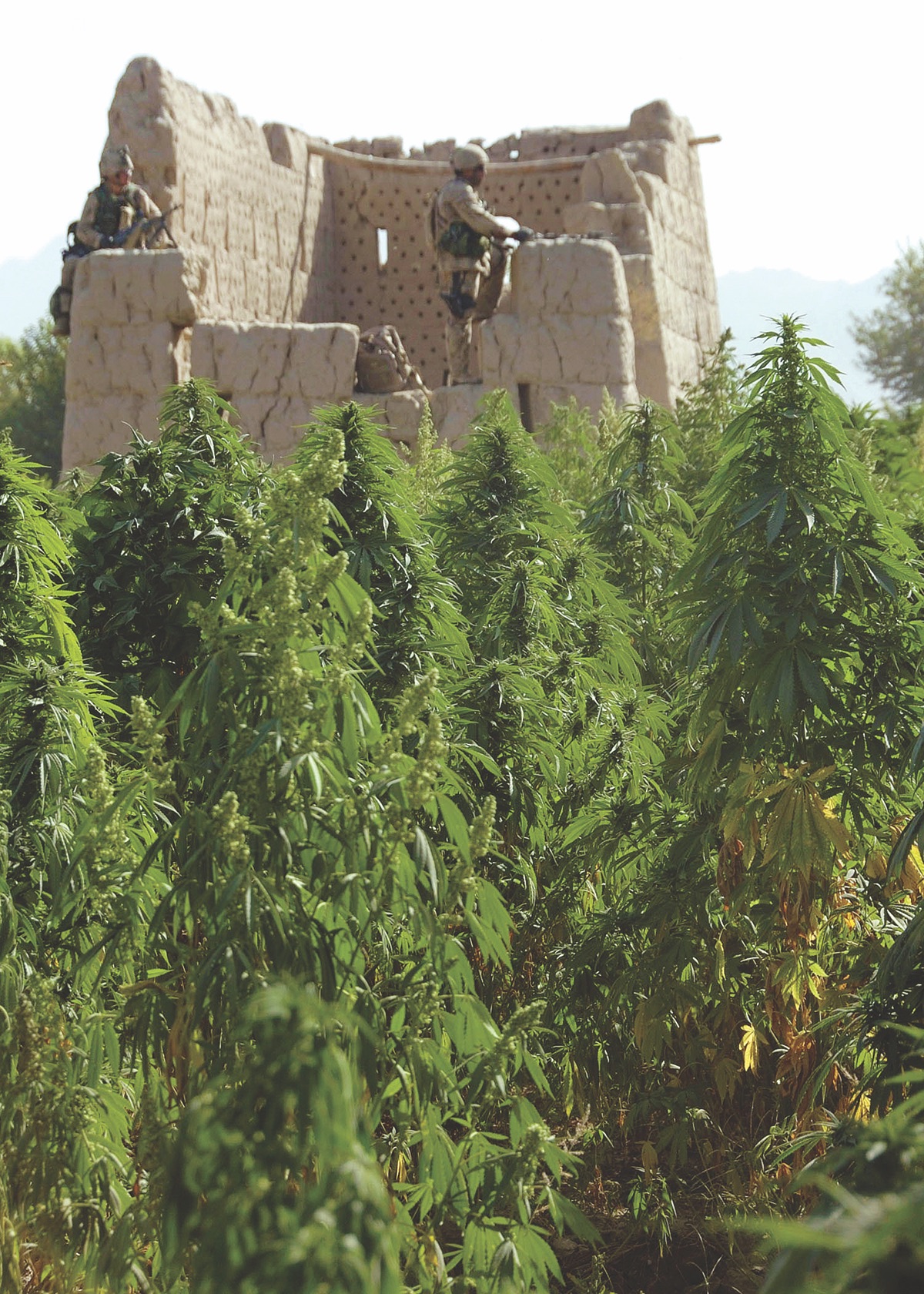

Just after 6 a.m. on September 3 the vanguard set out. Accompanying Charles’ 7 and 8 platoons were engineers, Afghan National Army soldiers and their American trainers, a tactical headquarters and a forward air controller. The group halted just after cresting the north bank of the wadi, taking up positions in a clearing bounded by fields of tall marijuana plants. There was no obvious activity in the buildings in front of them, but their senses were tingling. “Guys are looking at each other,” recalled Lt. Jeremy Hiltz, leading 8 Platoon. “There’s that feeling.”

Sprague, too, thought everything thus far had been too easy. He dispatched 8 Platoon, dismounted, to deal with a compound on the left flank, while the ANA moved north to watch the main road.

That left 7 Platoon to run straight up the middle toward the schoolhouse. Capt. Derek Wessan ordered his LAVs to shake out in battle line—from left, Bravo, Alpha and Charles (call sign 3-1), with his engineers in LAV Echo (3-2) on the right—followed by a G-Wagon (3-1W). Ordered to advance within 30 yards of the schoolhouse, they left the wadi and made their way through the marijuana field. Behind them Sprague, in LAV 3-9, pulled up atop the bank to watch the advance and add the punch of the vehicle’s 25 mm chain gun if needed.

Bright bursts interrupted the growing dawn as the Canadians’ artillery and air support commenced. Exerting surprising fire discipline, the Taliban waited until the LAVs halted in front of the schoolhouse before engaging. “The entire area just lit up,” remembered Master Cpl. Allan Johnson, commanding 3-1 Alpha. “We were taking fire from at least two sides, maybe three, with everything they had.” Sgt. Scott Fawcett, leaning out the rear sentry hatch of 3-1 Charlie, watched in amazement as an enemy round blew Echo 3-2’s turret skyward, instantly killing Sgt. Shane Stachnik, wounding another crewman and apparently putting the engineer LAV out of commission.

Simultaneously, an RPG smashed into the front of the G-Wagon, spraying shrapnel over its occupants and killing the platoon’s warrant officer, Rick Nolan. “Everything in the world came down on us,” recalled medic Corporal Richard Furoy, who was seated behind Nolan, “and then, whoomph, the G-Wagon went black.” Furoy and an Afghan interpreter beside him were severely wounded, but, remarkably, driver Corporal Sean Teal was only stunned.

Leaping out of 3-1 Charlie, Sgt. Fawcett grabbed Cpl. Jason Funnel and Pvt. Mike O’Rourke and ran toward the smoldering G-Wagon. Keeping low through the field, they could hear bullets crack overhead as marijuana tops rained down on them. Fawcett and Teal returned fire, while O’Rourke and Funnel rendered first aid and headed to the rear with the wounded.

Covering fire suddenly dropped off when 3-1 Bravo’s chain gun jammed. Disregarding incoming enemy rounds, Master Cpl. Sean Niefer hauled himself half out of the turret hatch to resume suppressing fire with his LAV’s pintle-mounted machine gun.

Improbably, Echo 3-2 roared back to life. Sprague had launched a recovery mission to pull the vehicle out of the kill zone, and at the moment the tow chain was being hooked up, the stunned driver regained consciousness, threw the LAV into reverse and got out of Dodge. Efforts to recover the G-Wagon proved futile, so Sprague ordered it blown in place.

But first, Sgt. John Russell volunteered to lead 3-1 Bravo out to the G-Wagon to retrieve Nolan’s body. There was no room for Teal and Fawcett, however, who were pinned down behind the shattered vehicle. They remained in the kill zone to cover Charles’ extrication until out of ammunition, then raced back to the company position. While driving 3-1 Bravo back out of the ambush, Cpl. Jason Ruffolo missed the access lane and put the LAV into a deep irrigation ditch, immobilizing it. When towing efforts failed, the crew, many of them wounded, abandoned the vehicle and Nolan’s body.

On the lip of the wadi, concealed if not sheltered by the tall plants, able-bodied men collected the wounded in the lee of one of the armored bulldozers. Hearing the firefight, a U.S. Army medic embedded with the Afghans soon arrived to assist. Tragically, the massive dozer took a direct hit from an enemy RPG, the resulting explosion killing Pvt. Will Cushley and severely wounding Warrant Officer Frank Mellish. Mellish lingered a few minutes but also died, despite Ruffolo’s best efforts to stop the bleeding.

Given his diminishing options, Sprague ordered an 8 Platoon LAV to recover Nolan’s body, and on that final sad note Charles Company retreated to lick its wounds. A day after advancing off Ma’sum Ghar, the men were back at their start line.

Fate was not yet finished with the company, however. The next morning tragedy struck again as the men were cleaning their equipment, burning garbage and preparing to move out. A U.S. Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt II fighter-bomber pilot flying combat air support lost situational awareness and unleashed a Gatling burst at the troops gathered around the flames. “We heard the burp of the gun,” Sgt. Brent Crellin recalled, “and then we felt sick.” Former Olympic track and field athlete Pvt. Mark Anthony Graham was killed, while Sprague and more than 30 others were wounded. The tactical headquarters and 8 Platoon had been savaged. Charles Company was left leaderless, understrength and combat ineffective.

By September 6 the survivors of Charles Company were back on Ma’sum Ghar, partnered with a nearly company-sized unit of Royal Canadian Dragoons, an American rifle company and a tactical headquarters led by U.S. Army Col. Steve Williams. Together they formed Task Force Grizzly. Williams was ordered to push up to the wadi but no farther, in keeping with the original plan.

The main effort was to be made from the north. The September 6 assault by 1 RCR’s Bravo Company was facilitated by the U.S. 10th Mountain Division’s Company A, 2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment, riding in Humvees. For four days the two units ground inexorably south. On September 11 Fraser ordered his forces on the south side of the Arghandab, including the remnants of Charles Company, to recross the wadi.

By that time the Taliban fighters had slipped the noose and were concentrating in Farah Province, far to the west. Operation Medusa limped on another six days, NATO forces spending most of their time clearing mines, IEDs and other booby traps. On Sunday, September 17, the operation was officially declared complete. Gen. David Richards, the British commander of NATO troops in Afghanistan, proclaimed Medusa a “significant success.”

On paper only four Canadians had been killed by hostile fire, all on the first day. The friendly fire incident had claimed a fifth. Taliban casualties, on the other hand, were estimated by Fraser to have been upward of 1,000 over the 15 days of fighting. The enemy had been soundly beaten and forced to flee. More important, according to NATO, the Taliban had been denied an essential base, one that had allowed them to threaten Kandahar. Seamless victory was NATO’s story—and it was sticking to it.

The Taliban begged to differ. The next day, in a response that might be described as thumbing one’s nose, a suicide bomber on a bicycle in Panjwai rode up to a Canadian foot patrol and detonated his explosive vest, killing himself and four soldiers. Evidently, the Taliban were still kicking a day after having been “defeated.”

In an interview with historian Col. Bernd Horn a month after Medusa, Fraser had the audacity to subtly praise his own combat sense. “It’s a feeling in battle,” he said, “when you got the enemy. It’s something you cannot teach—you just got to know when to push.” Members of Charles Company might very well wonder why that sixth sense had deserted him on September 3 when he’d suspended a planned preliminary bombardment and ordered them forward. That was Fraser’s first mistake. His second was sending that same fractured and disrupted company back into the fray on September 6, despite its having endured a horrifying friendly fire incident.

A dozen years after the battle Fraser’s opinion of himself has only grown. In 2018 he published a memoir titled Operation Medusa. The subtitle—The Furious Battle That Saved Afghanistan From the Taliban—speaks volumes. It is also wildly inaccurate. The day after Canadian commanders declared the enemy vanquished, the Taliban killed four infantrymen. Another three would die in Panjwai before year’s end.

Even as Fraser released his memoir, the Canadian news magazine Maclean’s underscored the impermanence of his victory:

The idyllic orchards and farm fields along the Arghandab River—which should have been teeming with laborers—instead provided cover for Taliban snipers.…Canadian soldiers continued to die in ambushes and suicide attacks. Convoys and foot patrols regularly struck roadside bombs that were planted overnight by local Taliban fighters. The death toll continued to climb, and by the time the Canadians left in 2011, it had reached 158.

Bob Gordon is a Canada-based historian whose work has been published in that nation, Britain and the United States. For further reading he recommends Canadian Forces in Afghanistan, by Colonel Bernd Horn and Emily Spencer, and Witness to War, by Adam Day.