In a controversial Cold War incident, a Korean Air Lines 707 was downed by a missile from a Soviet fighter, killing two passengers and touching off a diplomatic firestorm.

During the night of April 20-21, 1978, South Korean airliner KAL 902 disappeared on a polar flight from Paris to Seoul with a scheduled refueling stop in Anchorage, Alaska. The aircraft had strayed off course and penetrated the Soviet Union’s airspace, and then been struck by a missile from a Soviet fighter and forced to make an emergency landing on a frozen lake.

At the time I was the deputy principal officer of the U.S. Consulate General in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). I was tapped to travel to Murmansk and effect the turnover of the downed airliner’s passengers and crew, since at the time the United States represented South Korean interests in the Soviet Union. My involvement in the incident began with an embassy request to find out if Leningrad authorities had any information on the missing KAL 902 flight. The reply was curt: “Ask Moscow.” The two-word reply meant they did know something but it was too sensitive to be handled locally.

KAL 902 left Orly Airport in Paris a few minutes late at 1:39 p.m. on April 20, carrying 97 passengers—mostly Korean and Japanese with a smattering of Europeans—and 16 crew. The flight was Captain Kim Chang Kyu’s first on this polar route, though his navigator, Lee Kun Shik, had flown the route more than 120 times. The only unusual factor was that the aircraft on that day was an older Boeing 707 instead of the newer McDonnell Douglas DC-10 normally used for the flight.

After takeoff, the 707 climbed to its routine cruising altitude of 35,000 feet and settled into a cruise speed of 540 mph. Its course took it northwest over the North Sea past Britain, over the Faroe Islands and across the Greenland coast at Scoresbysund. Over Greenland, the aircraft passed out of range of ground control by radar, and the crew began relying solely on the airplane’s old-fashioned directional gyro guidance system. Five hours and 21 minutes into the nine-hour flight to Anchorage, the navigator reported to amateur stations in Canada and Norway that he was nearing the Canadian military station at Alert on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island.

After that, for reasons that pilot Kim attributed to a total guidance system failure, the aircraft began a turn toward the east, then to the south, taking it over the Barents Sea. It entered Soviet airspace near Murmansk and continued a slow arc back toward Finland. The turns were gradual enough to be initially undetected by the crew. Navigator Lee eventually realized that the plane was off course and attempted to contact several Loran stations he had used in the past, but none responded. Thereafter, he reverted to the plane’s onboard radar, which picked up a landmass that he took to be Alaska. He tried to establish his location by dead reckoning, but was unable to get a fix on any of his charts. At one point, the aircraft passed near a well-lit city that neither the pilot nor navigator could identify.

As they were puzzling over their whereabouts, copilot S.D. Cha suddenly noticed a jet fighter flying alongside at the same altitude, speed and direction as the airliner. With some difficulty, through the darkness he spotted a red star on the fighter’s tail, identifying it as Soviet.

What happened next is in dispute. The Soviets claimed the fighter (later identified as a Sukhoi Su-15TM interceptor) had been alongside the airliner a full 20 minutes and that the 707 had not responded to the fighter’s radio communications or hand signals to land. However, the KAL pilot claimed they only saw the fighter for a few minutes. Kim said he had immediately tried to communicate with the fighter by radio using internationally established emergency channels, but without success. He denied seeing any hand signals and contended that as soon as he noticed the fighter’s red star he turned on his navigational lights and began a descent to acknowledge that he was in Soviet airspace. He stressed that the Soviet aircraft had approached from the right (copilot’s) side, not from the left as required by the International Civil Aviation Organization’s rules. Kim added that the cabin crew, which was then just beginning breakfast preparations, also hadn’t noticed the approaching fighter.

Just as the airliner began its descent, the Su-15 fired two missiles. The first missed but the second took off the tip of the left wing. Fragments penetrated the fuselage, killing two passengers, seriously injuring two others and lightly injuring several more. Bahng Tais Hwang, a salesman from Seoul, died instantly from a wound to the head. Shrapnel mangled the right arm and shoulder of Yoshitako Sugano, who was sitting in a left side window seat. Sugano, a coffee shop owner from Yokohama, Japan, soon died from blood loss.

With cabin pressure gone, Kim immediately put the 707 into a steep dive, descending from 35,000 feet to around 4,000 feet, at the rate of 5,500 feet a minute. Passenger Seiko Shiozaki, 28, jotted notes in her diary during the incident, writing, “We felt…we are going to be dead. We are falling down, down, down.” Then the pilot leveled off and found that, with the wing damage, the airliner was now pulling sharply to the side but remained controllable. He searched for the fighter, intending to follow it to an emergency landing field, but claimed he never saw it again, nor any other aircraft. This contradicted later Soviet accounts that a second Su-15 had tried to lead the crippled airliner to a safe landing site.

By Kim’s account, the airliner flew until daybreak on the 21st looking for a landing site and using up fuel in preparation for an emergency landing. The landscape below was uneven and dotted with frozen lakes. He decided his best choice was to find a lake large enough to land the plane, preferably one with a village on its shore so that he could get prompt attention for the injured and care for the other passengers.

It was a risky proposition. Although the area was close to the Arctic Circle, Kim could not be sure of the quality of the lake ice that late in April. In the end, he decided to put the 707 down along the shore as close to land as possible so that if the airliner broke through the ice the passengers would still have a chance to get out safely. For this he needed a lake with a long, straight shoreline. The first suitable candidate had a power line stretching across it. The second had an island that posed a risk. But on his third try he found a suitable lake and put the aircraft down precisely as he had planned. Later even the Soviets expressed admiration at the skillful landing. Kim had landed on Lake Korpiyarvi in Soviet Karelia, less than 90 miles from the Finnish border.

Within minutes, local militia and townspeople arrived from the nearby village. The militiamen surrounded the aircraft, sealing it off from the townspeople and preventing anyone on the plane from leaving. To the pilot’s horror, they soon built a roaring fire near the damaged wingtip—whether to warm themselves or as a signal fire is unclear—and refused to douse it despite his frantic signaling that the wing was leaking fuel. Fortunately for the imprisoned crew and passengers, the drifting sparks proved harmless.

After a long delay, regular Soviet troops arrived. They took charge, promptly allowed the passengers and crew to deplane and took them to nearby Kem, a provincial city some 390 miles northeast of Leningrad. There passengers and crew were quartered in a military hotel, where they were treated with kindness by local citizens who looked after their needs.

The pilot, copilot and navigator were immediately separated from the other crew members and from each other for interrogation. The navigator was interrogated in Korean by an official hastily flown in from Moscow, while the pilot and copilot were questioned in English by a man describing himself as a local teacher.

The next day most of the crew and the passengers were informed that they would soon be released, flown to Murmansk and transferred to an evacuation flight. But the pilot and navigator were to be held and charged.

Meanwhile news that KAL 902 was missing had hit the media in Anchorage. Initial Soviet actions and press accounts were sympathetic and reassuring. In Moscow, the Soviet foreign ministry promptly informed the U.S. Embassy that the aircraft had “crash landed” in the area around Kem. It added that several passengers had been killed and injured in the crash, said no Americans were aboard and assured embassy officials that all passengers and crew would be released.

The foreign ministry also soon offered to let an American evacuation airliner fly into Murmansk, the nearest large city. This was an important concession since the airspace around that strategically important city was then closed to Westerners. In response, the embassy quickly located an available Pan American Boeing 727 in West Berlin. Within hours, on April 22, Moscow cleared it to proceed to Leningrad, where upon arrival it would be given the necessary radio frequencies, flight path and runway specifications for the subsequent leg to Murmansk.

However, the tone quickly became more confrontational. In Washington, President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, informed the media that the airliner had not crash landed but had been shot down. Domestically, this quickly led to Republican charges that Brzezinski had revealed classified intelligence information, but abroad news of the shootdown ignited rapid and widespread global condemnation.

The Soviet reaction was predictably defensive. In Tokyo, Soviet officials now revealed that not everyone on board the aircraft would be released. Simultaneously, both the Soviet news agency TASS and the Soviet foreign ministry began to speak of an “investigation,” while the U.S. Embassy was told darkly that the aircraft crew’s behavior was “erratic.” Publicly the Soviets struggled to put their own spin on the matter. They withheld details of the shootdown, refused to release the aircraft’s black box, suggested the KAL crew was partying and drunk, and circulated rumors that the airliner was a CIA spyplane.

Because the event occurred in the Leningrad consular district, responsibility for effecting the turnover of the downed airliner’s passengers and crew fell to that post. As the second-ranking person there, I was tasked with the assignment. Our consulate was also informed that three Japanese consular officers from Moscow would join us to provide services to the Japanese citizens aboard.

The 727 evacuation aircraft from Berlin arrived at the Leningrad airport during the afternoon of April 22. Our consular contingent boarded, and just before takeoff, the Soviets gave the pilot the promised flight plan, with a warning that it would be a “mistake” to deviate from it in any way.

The 727 arrived at Murmansk after dark on a bitterly cold night, and the consular contingent was met by a group of Soviet officials, including M. Reznichenko, a tough-minded officer from the Soviet foreign ministry. Shortly thereafter two aircraft landed with the KAL passengers and crew. Two passengers were heavily bandaged and several others showed signs of lesser injuries. Two sealed metal caskets also were unloaded.

The Japanese consular officers, who had brought KAL’s flight manifest from Moscow, began an immediate inventory, which accounted for everyone except the pilot and navigator. This was contrary to the earlier foreign ministry assurances that all passengers and crew would be released. The issue had to be resolved before the turnover could proceed to avoid any further escalation.

During several hours of inconclusive talks, I repeatedly reminded Reznichenko of the foreign ministry commitment and stressed that these assurances had to be honored. Reznichenko downplayed the absence of Kim and Lee as routine delays necessary simply to establish the facts of the incident, and offered repeated assurances that, after their temporary detention, the two would be released as promised.

Once it became clear that the situation in Murmansk was at an impasse, I reported by phone to the U.S. Embassy. David Weisz, who was heading an embassy watch group tracking the turnover, took the late night call. After some discussion, the embassy authorized the evacuation to proceed on humanitarian grounds. It later developed that the decision reflected additional high-level foreign ministry assurances in Moscow that the pilot and navigator would shortly be released. And the credibility of these further assurances was strengthened by the presence in Moscow at the time of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, who was there carrying out strategic arms control talks.

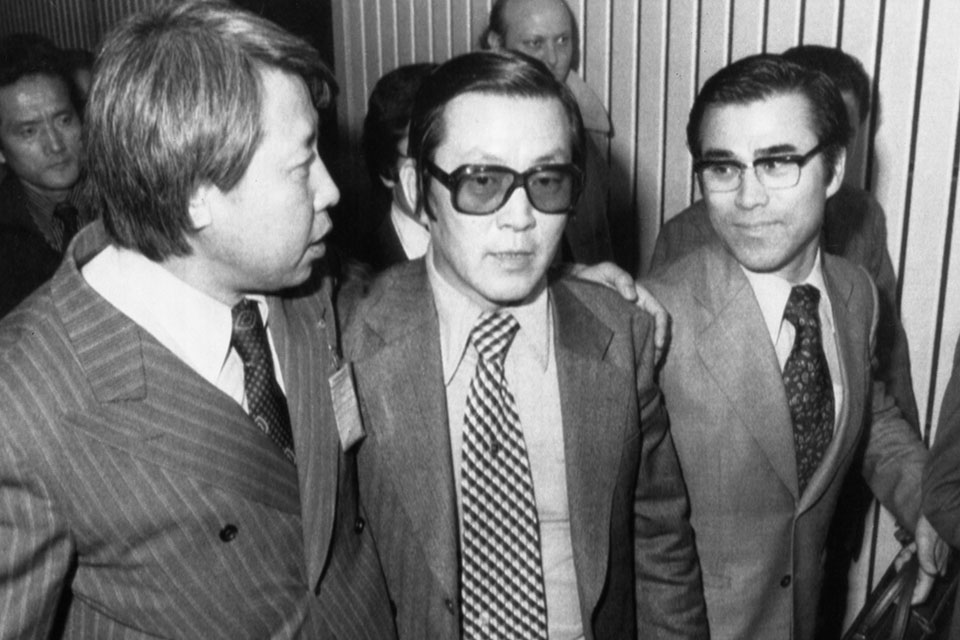

With the major issues settled, the pilot of the Pan Am evacuation plane, Francis H. Ricci; the copilot and engineer of the KAL airliner; Reznichenko; and an Aeroflot representative signed an official document early in the morning of April 23, turning over the released passengers and crew and the two coffins. The Pan Am 727 was then authorized to proceed on its prearranged flight to Helsinki. The short flight went smoothly, and when Captain Ricci announced that the aircraft had cleared Soviet airspace and was in Finland, a spontaneous cheer rose up. At Helsinki, KAL and consular officials facilitated onward passage of the released passengers and crew.

Meanwhile interrogations of the pilot and navigator continued in Kem. The two remained separated and were subjected to intensive questioning, lasting 13 hours the first day, nine the second and five to six hours each day thereafter. They were required to repeat their versions of the incident over and over with each iteration carefully compared to previous statements. They were not physically abused, but were under constant psychological pressure, including frequent confrontations over aspects of their story and threats of up to four years’ imprisonment.

It soon became clear to Kim and Lee that the Soviets were seeking a confession that would absolve the Soviet military of any wrongdoing. Increasingly the two were “encouraged” to admit that they, and they alone, were at fault. When they eventually did so, they were told to appeal to the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, Leonid Brezhnev, for “clemency.” On April 28 they complied with these demands, with the Soviets carefully editing their final wording. Shortly afterward the Soviet Presidium accepted the appeal. A week after the shootdown, Kim and Lee were released to the U.S. Consulate General in Leningrad, debriefed and flown to Copenhagen, escorted by a consular officer.

On April 30 the Soviets released a TASS communiqué that contained the essence of the Brezhnev appeal. TASS noted that both the pilot and navigator had pleaded guilty to “violating Soviet airspace” and “knowingly disobeying” orders from the Soviet interceptor. TASS attributed the incident entirely to failure of the airliner to abide by international flight rules and to obey the legitimate demands of the Soviet air defense. Both men, it claimed, had acknowledged that they had understood the orders of the Soviet fighter but had failed to follow them.

Some weeks later, a Soviet foreign ministry official told a U.S. Embassy officer that the shootdown had been triggered by a breakdown in the Soviet early-warning system. When first picked up on radar, KAL 902 was thought to be a U.S. surveillance craft testing Soviet airspace or running a spy mission. But then the plane had been allowed to cross over strategically sensitive Murmansk and penetrate deeply into Soviet territory. It was already nearing Finland when it was finally intercepted. The fighter pilot, Alexander Bosov, correctly identified the plane as a South Korean civilian airliner based on its markings, and reportedly tried to convince his superiors that it was not a threat. But the commander of Soviet air defense for the area, Vladimir Tsarkov, in a panic that it could be a trick, ordered the airliner shot down anyway without receiving prior permission from Moscow. The need to justify his action explains the intensive interrogations and hyped confessions. Despite this, Tsarkov was cashiered.

The downed 707 was a leased aircraft, and KAL made some initial efforts to recover it. The salvage crew found that the aircraft, especially the cockpit, had been ripped apart in an apparently futile effort to find spy paraphernalia. The gutted aircraft was cut up and taken by helicopter to a barge in nearby Kandalaksha. But it proved uneconomic to salvage beyond that point.

Korean Air Lines still flies KAL 902 from Paris to Seoul. The nonstop flight now departs from Charles de Gaulle Airport on an eastbound route that daily traverses nearly all of Russia.

George L. Rueckert’s account of the KAL 902 incident is based on his contemporaneous notes and interviews, including a debriefing of the KAL pilot and navigator, and on newspaper reports of the time.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!