Facts, information and articles about John F. Kennedy, the 35th U.S. President

John F. Kennedy Facts

Born

5/29/1917

Died

11/22/1963

Spouse

Jacqueline Bouvier

Years Of Military Service

1941-1945

Rank

Lieutenant

Accomplishments

Navy and Maine Corps Medal

Purple Heart

American Campaign Medal

Asiatio-Pacific Campaign Medal

World War II Victory Medal

35th President Of the United States

John F. Kennedy Articles

![By Cecil Stoughton, White House [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/John_F._Kennedy%2C_White_House_color_photo_portrait.jpg/256px-John_F._Kennedy%2C_White_House_color_photo_portrait.jpg) John F. Kennedy summary: John F. Kennedy was the 35th president of the United States. He was born in 1917 into a wealthy family with considerable political ties. Kennedy studied Political Science at Harvard University. He later served as a lieutenant in the Navy, where he earned a Purple Heart, among other honors, during World War II. After leaving the Navy, Kennedy worked as a journalist for several years. He later went on to serve three terms in House of Representatives, followed by a term as senator from 1953 to 1961. He wrote a Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Profiles in Courage. In 1953, he married Jacqueline “Jackie” Bouvier, a photographer-columnist for the Washington Times-Herald. The couple came to be regarded almost as American royalty; he was popular due to his charm, good looks, and vitality, and Jackie became an icon of fashion and grace who was active in promoting the arts and historic preservation. In 1960, Kennedy won the presidential election by a very narrow margin but carried the electoral college 303–219, beating Richard Nixon to become the 35th president of the United States. He was the youngest man and first Catholic to hold that office.

John F. Kennedy summary: John F. Kennedy was the 35th president of the United States. He was born in 1917 into a wealthy family with considerable political ties. Kennedy studied Political Science at Harvard University. He later served as a lieutenant in the Navy, where he earned a Purple Heart, among other honors, during World War II. After leaving the Navy, Kennedy worked as a journalist for several years. He later went on to serve three terms in House of Representatives, followed by a term as senator from 1953 to 1961. He wrote a Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Profiles in Courage. In 1953, he married Jacqueline “Jackie” Bouvier, a photographer-columnist for the Washington Times-Herald. The couple came to be regarded almost as American royalty; he was popular due to his charm, good looks, and vitality, and Jackie became an icon of fashion and grace who was active in promoting the arts and historic preservation. In 1960, Kennedy won the presidential election by a very narrow margin but carried the electoral college 303–219, beating Richard Nixon to become the 35th president of the United States. He was the youngest man and first Catholic to hold that office.

During his presidency, Kennedy gave many inspiring speeches; these speeches, rather than his legislative accomplishments, became his legacy. He did help to further the civil rights movement, but most of the legislature he initiated did not become law during his presidency. On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Texas. His assassination raised questions of a possible conspiracy that are still being debated today. His life and death have been the subject of numerous books, documentaries and feature films.

Articles Featuring John F. Kennedy From HistoryNet Magazines

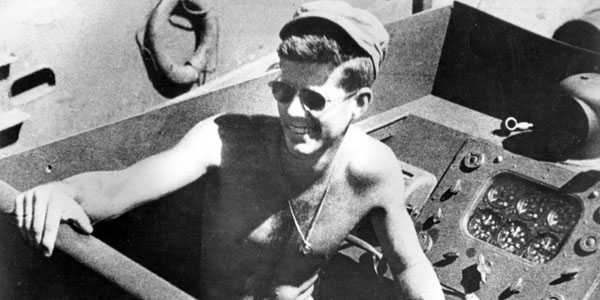

Read More About JFK in WWII

The Truth About Devil Boats

The Kennedy Curse in WWII

Letter From MHQ, Spring 2011

Featured Article

John F. Kennedy’s PT-109 Disaster

The most famous collision in U.S. Navy history occurred at about 2:30 a.m. on August 2, 1943, a hot, moonless night in the Pacific. Patrol Torpedo boat 109 was idling in Blackett Strait in the Solomon Islands. The 80-foot craft had orders to attack enemy ships on a resupply mission. With virtually no warning, a Japanese destroyer emerged from the black night and smashed into PT-109, slicing it in two and igniting its fuel tanks. The collision was part of a wild night of blunders by 109 and other boats that one historian later described as “the most screwed up PT boat action of World War II.” Yet American newspapers and magazines reported the PT-109 mishap as a triumph. Eleven of the 13 men aboard survived, and their tale, declared the Boston Globe, “was one of the great stories of heroism in this war.” Crew members who were initially ashamed of the accident found themselves depicted as patriots of the first order, their behavior a model of valor.

The PT-109 disaster made JFK a hero. But his fury and grief at the loss of two men sent him on a dangerous quest to get even.

The Globe story and others heaped praise on Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy, commander of the 109 and son of the millionaire and former diplomat Joseph Kennedy. KENNEDY’S SON IS HERO IN PACIFIC AS DESTROYER SPLITS HIS PT BOAT, declared a New York Times headline. It was Kennedy’s presence, of course, that made the collision big news. And it was his father’s media savvy that helped turn an embarrassing disaster into a tale worthy of Homer.

Airbrushed from this PR confection was Lieutenant Kennedy’s reaction to the accident. The young officer was deeply pained by the death of two of his men in the collision. Returning to duty in command of a new breed of PT boat, he lobbied for dangerous assignments and displayed a recklessness that worried fellow officers. Kennedy, they said, was hell-bent on redeeming himself and getting revenge on the Japanese.

Kennedy would later embrace the myths of PT-109 and ride them into the White House. But in his last months in combat, he appeared to be a troubled young man trying to make peace with what happened that dark night in the Solomons.

Jack Kennedy was sworn in as an ensign on September 25, 1941. At 24, he was already something of a celebrity. With financial backing from his father and the help of New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, he had turned his 1939 Harvard thesis into Why England Slept, a bestseller about Britain’s failure to rearm to meet the threat of Hitler.

Getting young Jack into the navy took similar finagling. As one historian put it, Kennedy’s fragile health meant he was not qualified for the Sea Scouts, much less the U.S. Navy. From boyhood, he had suffered from chronic colitis, scarlet fever, and hepatitis. In 1940, the U.S. Army’s Officer Candidate School had rejected him as 4-F, citing ulcers, asthma, and venereal disease. Most debilitating, doctors wrote, was his birth defect—an unstable and often painful back.

When Jack signed up for the navy, his father pulled strings to ensure his poor health did not derail him. Captain Alan Goodrich Kirk, head of the Office of Naval Intelligence, had been the naval attaché in London before the war when Joe Kennedy had served as ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. The senior Kennedy persuaded Kirk to let a private Boston doctor certify Jack’s good health.

Kennedy was soon enjoying life as a young intelligence officer in the nation’s capital, where he started keeping company with 28-year-old Inga Marie Arvad, a Danish-born reporter already twice married but now separated from her second husband, a Hungarian film director. They had a torrid affair—many biographers say she was the true love of Kennedy’s life—but the relationship became a threat to his naval career. Arvad had spent time reporting in Berlin and had grown friendly with Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and other prominent Nazis—ties that raised suspicions she was a spy.

Kennedy was soon enjoying life as a young intelligence officer in the nation’s capital, where he started keeping company with 28-year-old Inga Marie Arvad, a Danish-born reporter already twice married but now separated from her second husband, a Hungarian film director. They had a torrid affair—many biographers say she was the true love of Kennedy’s life—but the relationship became a threat to his naval career. Arvad had spent time reporting in Berlin and had grown friendly with Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and other prominent Nazis—ties that raised suspicions she was a spy.

Kennedy eventually broke up with Arvad, but the imbroglio left him depressed and exhausted. He told a friend he felt “more scrawny and weak than usual.” He developed excruciating pain in his lower back. Jack consulted with his doctor at the Lahey Clinic in Boston, and asked for a six-month leave for surgery. Lahey doctors as well as specialists at the Mayo Clinic diagnosed chronic dislocation of the right sacroiliac joint, which could only be cured by spinal fusion.

Navy doctors weren’t so sure that Kennedy needed surgery. He spent two months at naval hospitals, after which his problem was incorrectly diagnosed as muscle strain. The treatment: exercise and medication.

During Jack’s medical leave, the navy won the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. Ensign Kennedy emerged from his sickbed ferociously determined to see action. He persuaded Undersecretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, an old friend of his father, to get him into Midshipman’s School at Northwestern University. Arriving in July 1942, he plunged into two months of studying navigation, gunnery, and strategy.

During that time, Lieutenant Commander John Duncan Bulkeley visited the school. Bulkeley was a freshly minted national hero. As commander of a PT squadron, he had whisked General Douglas MacArthur and family from the disaster at Bataan, earning a Medal of Honor and fame in the book They Were Expendable. Bulkeley claimed his PTs had sunk a Japanese cruiser, a troopship, and a plane tender in the struggle for the Philippines, none of which was true. He was now touring the country promoting war bonds and touting the PT fleet as the Allies’ key to victory in the Pacific.

At Northwestern, Bulkeley’s tales of adventure inspired Kennedy and nearly all his 1,023 classmates to volunteer for PT duty. Although only a handful were invited to attend PT training school in Melville, Rhode Island, Kennedy was among them. Weeks earlier, Joe Kennedy had taken Bulkeley to lunch and made it clear that command of a PT boat would help his son launch a political career after the war.

Once in Melville, Jack realized that Bulkeley had been selling a bill of goods. Instructors warned that in a war zone, PTs must never leave harbor in daylight. Their wooden hulls could not withstand even a single bullet or bomb fragment. The tiniest shard of hot metal might ignite the 3,000-gallon gas tanks. Worse, their 1920s-vintage torpedoes had a top speed of only 28 knots—far slower than most of the Japanese cruisers and destroyers they would target. Kennedy joked that the author of They Were Expendable ought to write a sequel titled They Are Useless.

On April 14, 1943, having completed PT training, Kennedy arrived on Tulagi, at the southern end of the Solomon Islands. Fifteen days later, he took command of PT-109. American forces had captured Tulagi and nearby Guadalcanal, but the Japanese remained entrenched on islands to the north. The navy’s task: Stop enemy attempts to reinforce and resupply these garrisons.

Except for the executive officer—Ensign Leonard Thom, a 220-pound former tackle at Ohio State—PT-109’s crew members were all as green as Kennedy. The boat was a wreck. Its three huge Packard motors needed a complete overhaul. Scum fouled its hull. The men worked until mid-May to ready it for sea. Determined to prove he was not spoiled, Jack joined his crew scraping and painting the hull. They liked his refusal to pull rank. They liked even more the ice cream and treats that the lieutenant bought them at the PX. Jack also made friends with his squadron’s commanding officer, 24-year-old Alvin Cluster, one of the few Annapolis graduates to volunteer for the PTs. Cluster shared Jack’s sardonic attitude toward the protocol and red tape of the “Big Navy.”

On May 30, Cluster took PT-109 with him when he was ordered to move two squadrons 80 miles north to the central Solomons. Here Kennedy made a reckless gaffe. After patrols, he liked to race back to base to snare the first spot in line for refueling. He would approach the dock at top speed, reversing his engines only at the last minute. Machinist’s Mate Patrick “Pop” McMahon warned that the boat’s war-weary engines might conk out, but Kennedy paid no heed. One night, the engines finally did fail, and the 109 smashed into the dock like a missile. Some commanders might have court-martialed Kennedy on the spot. But Cluster laughed it off, particularly when his friend earned the nickname “Crash” Kennedy. Besides, it was a mild transgression compared to the blunders committed by other PT crews, whom Annapolis grads called the Hooligan Navy. [See sidebar “The Truth About “Devil Boats.”]

On July 15, three months after Kennedy arrived in the Pacific, PT-109 was ordered to the central Solomons and the island of Rendova, close to heavy fighting on New Georgia. Seven times in the next two weeks, 109 left its base on Lumbari Island, a spit of land in the Rendova harbor, to patrol. It was tense, exhausting work. Though PTs patrolled only at night, Japanese floatplane crews could spot their phosphorescent wakes. The planes often appeared without warning, dropped a flare, and then followed with bombs. Japanese barges, meanwhile, were equipped with light cannons far superior to the PTs’ machine guns and single 20mm gun. Most unnerving were the enemy destroyers running supplies and reinforcements to Japanese troops in an operation the Americans called the Tokyo Express. Cannons from these ships could blast the PTs into splinters.

On one patrol, a Japanese floatplane spotted the PT-109. A near miss showered the boat with shrapnel that slightly wounded two of the crew. Later, floatplane bombs bracketed another PT boat and sent the 109 skittering away in frantic evasive maneuvers. One of the crew, 25-year-old Andrew Jackson Kirksey, became convinced he was going to die and unnerved others with his morbid talk. To increase the boat’s firepower, Kennedy scrounged up a 37mm gun and fastened it with rope on the forward deck. The 109’s life raft was discarded to make room.

Finally came the climactic night of August 1 and 2, 1943. Lieutenant Commander Thomas Warfield, an Annapolis graduate, was in charge at the base on Lumbari. He received a flash message that the Tokyo Express was coming out from Rabaul, the Japanese base far to the north on New Guinea. Warfield dispatched 15 boats, including PT-109, to intercept, organizing the PTs into four groups. Riding with Kennedy was Ensign Barney Ross, whose boat had recently been wrecked. That brought the number of men aboard to 13—a number that spooked superstitious sailors.

Lieutenant Hank Brantingham, a PT veteran who had served with Bulkeley in the famous MacArthur rescue, led the four boats in Kennedy’s group. They motored away from Lumbari at about 6:30 p.m., heading northwest to Blackett Strait, between the small island of Gizo and the bigger Kolombangara. The Tokyo Express was headed to a Japanese base at the southern tip of Kolombangara.

A few minutes after midnight, with all four boats lying in wait, Brantingham’s radar man picked up blips hugging the coast of Kolombangara. The Tokyo Express was not expected for another hour; the lieutenant concluded the radar blips were barges. Without breaking radio silence, he charged off to engage, presuming the others would follow. The nearest boat, commanded by veteran skipper William Liebenow, joined him, but Kennedy’s PT-109 and the last boat, with Lieutenant John Lowrey at the helm, somehow got left behind.

Opening his attack, Brantingham was surprised to discover his targets were destroyers, part of the Tokyo Express. High-velocity shells exploded around his boat as well as Liebenow’s. Brantingham fired his torpedoes but missed. At some point, one of his torpedo tubes caught fire, illuminating his boat as a target. Liebenow fired twice and also missed. With that, the two American boats made a hasty retreat.

Kennedy and Lowrey remained oblivious. But they were not the only patrol stumbling around in the dark. The 15 boats that had left Lumbari that evening fired at least 30 torpedoes, yet hit nothing. The Tokyo Express steamed through Blackett Strait and unloaded 70 tons of supplies and 900 troops on Kolombangara. At about 1:45 a.m., the four destroyers set out for the return trip to Rabaul, speeding north.

Kennedy and Lowrey remained in Blackett Strait, joined now by a third boat, Lieutenant Phil Potter’s PT-169, which had lost contact with its group. Kennedy radioed Lumbari and was told to try to intercept the Tokyo Express on its return.

With the three boats back on patrol, a PT to the south spotted one of the northbound destroyers and attacked, without success. The captain radioed a warning: The destroyers are coming. At about 2:30 a.m., Lieutenant Potter in PT-169 saw the phosphorescent wake of a destroyer. He later said that he, too, radioed a warning.

Aboard PT-109, however, there was no sense of imminent danger. Kennedy received neither warning, perhaps because his radioman, John Maguire, was with him and Ensign Thom in the cockpit. Ensign Ross was on the bow as a lookout. McMahon, the machinist’s mate, was in the engine room. Two members of the crew were asleep, and two others were later described as “lying down.”

Harold Marney, stationed at the forward turret, was the first to see the destroyer. The Amagiri, a 2,000-ton ship four times longer than the 109, emerged out of the black night on the starboard side, about 300 yards away and bearing down. “Ship at two o’clock!” Marney shouted.

Kennedy and the others first thought the dark shape was another PT boat. When they realized their mistake, Kennedy signaled the engine room for full power and spun the ship’s wheel to turn the 109 toward the Amagiri and fire. The engines failed, however, and the boat was left drifting. Seconds later, the destroyer, traveling at 40 knots, slammed into PT-109, slicing it from bow to stern. The crash demolished the forward gun turret, instantly killing Marney and Andrew Kirksey, the enlisted man obsessed with his death.

In the cockpit, Kennedy was flung violently against the bulkheads. Prone on the deck, he thought: This is how it feels to be killed. Gasoline from the ruptured fuel tanks ignited. Kennedy gave the order to abandon ship. The 11 men leaped into the water, including McMahon, who had been badly burned as he fought his way to the deck through the fire in the engine room.

After a few minutes, the flames from the boat began to subside. Kennedy ordered everyone back aboard the part of the PT-109 still afloat. Some men had drifted a hundred yards into the darkness. McMahon was almost helpless. Kennedy, who’d been on the Harvard swim team, took charge of him and pulled him back to the boat.

Dawn found the men clinging to the tilting hulk of PT-109, which was dangerously close to Japanese-controlled Kolombangara. Kennedy pointed toward a small bit of land about four miles away—Plum Pudding Island—that was almost certainly uninhabited. “We’ve got to swim to that,” he said.

They set out from the 109 around 1:30 p.m. Kennedy towed McMahon, gripping the strap of the injured man’s life jacket in his teeth. The journey took five exhausting hours, as they fought a strong current. Kennedy reached the beach first and collapsed, vomiting salt water.

Worried that McMahon might die from his burns, Kennedy left his crew near sundown to swim into Ferguson Passage, a feeder to Blackett Strait. The men begged him not to take the risk, but he hoped to find a PT boat on a night patrol. The journey proved harrowing. Stripped to his underwear, Kennedy walked along a coral reef that snaked far out into the sea, perhaps nearly to the strait. Along the way, he lost his bearings, as well as his lantern. At several points, he had to swim blindly in the dark.

Back on Plum Pudding Island, the men had nearly given their commander up for dead when he stumbled across the reef at noon the next day. It was the first of several trips that Kennedy made into Ferguson Passage to find help. Each failed. But his courage earned the lieutenant his men’s loyalty for life.

Over the next few days, Kennedy put up a brave front, talking confidently of their rescue. When Plum Pudding’s coconuts—their only food—ran short, he moved the survivors to another island, again towing McMahon through the water.

Eventually, the men were found by two natives who were scouts for a coastwatcher, a New Zealand reserve officer doing reconnaissance. Their rescue took time to engineer, but at dawn on August 8, six days after the 109 was hit, a PT boat pulled into the American base carrying the 11 survivors.

On board were two wire-service reporters who had jumped at the chance to report on the rescue of the son of Joseph Kennedy. Their stories and others exploded in newspapers, with dramatic accounts of Kennedy’s exploits. But the story that would define the young officer as a hero ran much later, after his return to the States in January 1944.

By chance, Kennedy met up for drinks one night at a New York nightclub with writer John Hersey, an acquaintance who had married one of Jack’s former girlfriends. Hersey proposed doing a PT-109 story for Life magazine. Kennedy consulted his father the next day. Joe Kennedy, who hoped to secure his son a Medal of Honor, loved the idea.

The 29-year-old Hersey was an accomplished journalist and writer. His first novel, A Bell for Adano, was published the same week he met Kennedy at the nightclub; it would win a Pulitzer in 1945. Hersey had big ambitions for the PT-109 article; he wanted to use devices from fiction in a true-life story. Among the tricks to try out: telling the story from the perspective of the people involved and lingering on their feelings and emotions—something frowned upon in journalism of the day. In his retelling of the PT-109 disaster, the crew members would be like characters in a novel.

Kennedy, of course, was the protagonist. Describing his swim into the Ferguson Passage from Plum Pudding Island, Hersey wrote: “A few hours before he had wanted desperately to get to the base at [Lumbari]. Now he only wanted to get back to the little island he had left that night….His mind seemed to float away from his body. Darkness and time took the place of a mind in his skull.”

Life turned down Hersey’s literary experiment—probably because of its length and novelistic touches—but the New Yorker published the story in June. Hersey was pleased—it was his first piece for the heralded magazine—but it left Joe Kennedy in a black mood. He regarded the relatively small-circulation New Yorker as a sideshow in journalism. Pulling strings, Joe persuaded the magazine to let Reader’s Digest publish a condensation, which the tony New Yorker never did.

This shorter version, which focused almost exclusively on Jack, reached millions of readers. The story helped launch Kennedy’s political career. Two years later, when he ran for Congress from Boston, his father paid to send 100,000 copies to voters. Kennedy won handily.

That campaign, according to scholar John Hellman, marks the “true beginning” of the Kennedy legend. Thanks to Hersey’s evocative portrait and Joe Kennedy’s machinations, Hellman writes, the real-life Kennedy “would merge with the ‘Kennedy’ of Hersey’s text to become a popular myth.”

Hersey’s narrative devoted remarkably few words to the PT-109 collision itself—at least in part because the writer was fascinated by what Kennedy and his men did to survive. (His interest in how men and women react to life-threatening pressures would later take him to Hiroshima, where he did a landmark New Yorker series about survivors of the nuclear blast.) Hersey also stepped lightly around the question of whether Kennedy was responsible.

The navy’s intelligence report on the loss of the PT-109 was also mum on the subject. As luck would have it, another Kennedy friend, Lieutenant (j.g.) Byron “Whizzer” White, was selected as one of two officers to investigate the collision. An All-America running back in college, White had first met Kennedy when the two were in Europe before the war—White as a Rhodes scholar, Kennedy while traveling. They had shared a few adventures in Berlin and Munich. As president, Kennedy would appoint White to the Supreme Court.

In the report, White and his coauthor described the collision matter-of-factly and devoted almost all the narrative to Kennedy’s efforts to find help. Within the command ranks of the navy, however, Kennedy’s role in the collision got a close look. Though Alvin Cluster recommended his junior officer for the Silver Star, the navy bureaucracy that arbitrates honors chose to put up Kennedy only for the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, a noncombat award. This downgrade hinted that those high up in the chain of command did not think much of Kennedy’s performance on the night of August 2. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox let the certificate confirming the medal sit on his desk for several months.

It wasn’t until fate intervened that Kennedy got his medal: On April 28, 1944, Knox died of a heart attack. Joe Kennedy’s friend James Forrestal—who helped Jack win transfer to the Pacific—became secretary. He signed the medal certificate on the same day that he was sworn in.

In the PT fleet, some blamed “Crash” Kennedy for the collision. His crew should have been on high alert, they said. Warfield, the commander at Lumbari that night, later claimed that Kennedy “wasn’t a particularly good boat commander.” Lieutenant Commander Jack Gibson, Warfield’s successor, was even tougher. “He lost the 109 through very poor organization of his crew,” Gibson later said. “Everything he did up until he was in the water was the wrong thing.”

Other officers blamed Kennedy for the failure of the 109’s engine when the Amagiri loomed into sight. He had been running on only one engine, and PT captains well knew that abruptly shoving the throttles to full power often killed the engines.

There was also the matter of the radio warnings. Twice, other PT boats had signaled that the Tokyo Express was headed north to where the 109 was patrolling. Why wasn’t Kennedy’s radioman below deck monitoring the airwaves?

Some of this criticism can be discounted. Warfield had to answer for mistakes of his own from that wild night. Gibson, who was not even at Lumbari, can be seen as a Monday-morning quarterback. As for the radio messages, Kennedy’s patrol group was operating under an order of radio silence. If the 109 assumed that order banned radio traffic, why bother monitoring the radio?

There’s also a question of whether the navy adequately prepared Kennedy’s men, or any of the PT crews. Though the boats patrolled at night, no evidence suggests they were trained to see long distances in darkness—a skill called night vision. As a sailor aboard the light cruiser Topeka (CL-67) in 1945 and 1946, this writer and his shipmates were trained in the art and science of night vision. The Japanese, who were the first to study this talent, taught a cadre of sailors to see extraordinary distances. At the 1942 night battle of Savo Island, in which the Japanese destroyed a flotilla of American cruisers, their lookouts first sighted their targets almost two and a half miles away.

No one aboard PT-109 knew how to use night vision. With it, Kennedy or one of the others might have picked the Amagiri out of the night sooner.

However valid, the criticism of his command must have reached Kennedy. He might have shrugged off the putdowns of other PT skippers, but it must have been harder to ignore the biting words of his older brother. At the time of the crash, 28-year-old Joe Kennedy Jr. was a navy bomber pilot stationed in Norfolk, Virginia, waiting for deployment to Europe. He was tall, handsome, and—unlike Jack—healthy. His father had long ago anointed him as the family’s best hope to reach the White House.

Joe and Jack were bitter rivals. When Joe read Hersey’s story, he sent his brother a letter laced with barbed criticism. “What I really want to know,” he wrote, “is where the hell were you when the destroyer hove into sight, and exactly what were your moves?”

Kennedy never answered his brother. Indeed, little is known about how he rated his performance on the night of August 2. But there is evidence that he felt enormous guilt—that Joe’s questions struck a nerve. Kennedy had lost two men, and he was clearly troubled by their deaths.

After the rescue boats picked up the 109 crew, Kennedy kept to his bunk on the return to Lumbari while the other men happily filled the notebooks of the reporters on board. Later, according to Alvin Cluster, Kennedy wept. He was bitter that other PT boats had not moved in to rescue his men after the wreck, Cluster said. But there was more.

“Jack felt very strongly about losing those two men and his ship in the Solomons,” Cluster said. “He…wanted to pay the Japanese back. I think he wanted to recover his self-esteem.”

At least one member of the 109 felt humiliated by what happened in Blackett Strait—and was surprised that Hersey’s story wrapped them in glory. “We were kind of ashamed of our performance,” Barney Ross, the 13th man aboard, said later. “I had always thought it was a disaster, but [Hersey] made it sound pretty heroic, like Dunkirk.”

Kennedy spent much of August in sickbay. Cluster offered to send the young lieutenant home, but he refused. He also put a stop to his father’s efforts to bring him home.

By September, Kennedy had recovered from his injuries and was panting for action. About the same time, the navy finally recognized the weaknesses of its PT fleet. Work crews dismantled the torpedo tubes and screwed armor plating to the hulls. New weapons bristled from the deck—two .50-caliber machine guns and two 40mm cannons.

Promoted to full lieutenant in October, Jack became one of the first commanders of the new gunboats, taking charge of PT-59. He told his father not to worry. “I’ve learned to duck,” he wrote, “and have learned the wisdom of the old naval doctrine of keeping your bowels open and your mouth shut, and never volunteering.”

But from late October through early November, Kennedy took the PT-59 into plenty of action from its base on the island of Vella Lavella, a few miles northwest of Kolombangara. Kennedy described those weeks as “packed with a great deal in the way of death.” According to the 59’s crew, their commander volunteered for the riskiest missions and sought out danger. Some balked at going out with him. “My God, this guy’s going to get us all killed!” one man told Cluster.

Kennedy once proposed a daylight mission to hunt hidden enemy barges on a river on the nearby island of Choiseul. One of his officers argued that this was suicide; the Japanese would fire on them from both banks. After a tense discussion, Cluster shelved the expedition. All along, he harbored suspicions that the PT-109 incident was clouding his friend’s judgment. “I think it was the guilt of losing his two crewmen, the guilt of losing his boat, and of not being able to sink a Japanese destroyer,” Cluster said later. “I think all these things came together.”

On November 2, Kennedy saw perhaps his most dramatic action on PT-59. In the afternoon, a frantic plea reached the PT base from an 87-man Marine patrol fighting 10 times that many Japanese on Choiseul. Although his gas tanks were not even half full, Kennedy roared out to rescue more than 50 Marines trapped on a damaged landing craft that was taking on water. Ignoring enemy fire from shore, Kennedy and his crew pulled alongside and dragged the Marines aboard.

Overloaded, the gunboat struggled to pull away, but eventually it sped off in classic PT style, with Marines clinging to gun mounts. About 3 a.m., on the trip back to Vella Lavella, the boat’s gas tanks ran dry. PT-59 had to be towed to base by another boat.

Such missions took a toll on Jack’s weakened body. Back and stomach pain made sleep impossible. His weight sank to 120 pounds, and bouts of fever turned his skin a ghastly yellow. Doctors in mid-November found a “definite ulcer crater” and “chronic disc disease of the lower back.” On December 14, nine months after he arrived in the Pacific, he was ordered home.

Back in the States, Kennedy appeared to have lost the edge that drove him on PT-59. He jumped back into the nightlife scene and assorted romantic dalliances. Assigned in March to a cushy post in Miami, he joked, “Once you get your feet upon the desk in the morning, the heavy work of the day is done.”

By the time Kennedy launched his political career in 1946, he clearly recognized the PR value of the PT-109 story. “Every time I ran for office after the war, we made a million copies of [the Reader’s Digest] article to throw around,” he told Robert Donovan, author of PT-109: John F. Kennedy in World War II. Running for president, he gave out PT-109 lapel pins.

Americans loved the story and what they thought it said about their young president. Just before he was assassinated, Hollywood released a movie based on Donovan’s book and starring Cliff Robertson.

Still, Kennedy apparently couldn’t shake the deaths of his two men in the Solomons. After the Hersey story came out, a friend congratulated him and called the article a lucky break. Kennedy mused about luck and whether most success results from “fortuitous accidents.”

“I would agree with you that it was lucky the whole thing happened if the two fellows had not been killed.” That, he said, “rather spoils the whole thing for me.”

This story was originally published in MHQ Magazine. For more stories, subscribe here.

Featured Article

President John F. Kennedy’s Civil Rights Quandary

In the two years after he became president, John F. Kennedy faced no more daunting domestic issue than the tension between African Americans demanding equal treatment under the Constitution and segregationists refusing to end the South’s system of apartheid. While Kennedy tried to ease the problem with executive actions that expanded black voting, job opportunities and access to public housing, he consistently refused to put a major civil rights bill before Congress.

He believed that a combination of Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans would defeat any such measure and jeopardize the rest of his legislative agenda, which included a large tax cut, federal aid to elementary and secondary education, and medical insurance for the elderly. His restraint, however, did little to appease Southern legislators, who consistently helped block his other reforms.

When a civil rights crisis erupted in Birmingham, Alabama, in the spring of 1963, Kennedy considered shifting ground and pressing for congressional action. In May, as black demonstrators, including many high school and some elementary school children, marched in defiance of a city ban, police and firemen attacked the marchers with police dogs that bit several demonstrators and high-pressure fire hoses that knocked marchers down and tore off their clothes. The TV images, broadcast across the country and around the world, graphically showed out-of-control racists abusing innocent young advocates of equal rights. Kennedy, looking at a picture on the front page of The New York Times of a dog lunging to bite a teenager on the stomach, said that the photo made him sick.

But Kennedy’s response was more than visceral. He saw an end to racial strife in the South as essential to America’s international standing in its competition with Moscow for influence in Third World countries. Moreover, Kennedy feared that as many as 30 Southern cities might explode in violence during the summer. The prospect of race wars across the South convinced him that he had to take bolder action. Burke Marshall, the assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, recalled that the president now saw Birmingham as representative of a pattern that “would recur in many other places.” JFK, Marshall said, “wanted to know what he should do—not to deal with Birmingham, but to deal with what was clearly an explosion in the racial problem that could not, would not, go away, that he had not only to face up to himself, but somehow to bring the country to face up to and resolve.”

Kennedy concluded that he now had to ask Congress for a major civil rights bill that would offer a comprehensive response to the problem. Kennedy told aides: “The problem is [that] there is no other remedy for them [the black rioters]. This will give another remedy in law. Therefore, this is the right message. It will remove the [incentive] to mob action.” On June 11, Kennedy made the decision to give a televised evening speech announcing his civil rights bill proposal. With only six hours to prepare, it was uncertain that his counselor and speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, would be able to deliver a polished text in time. The president and his attorney general brother, Bobby, discussed what he should say in an extemporaneous talk should no text be ready. Five minutes before Kennedy went on television, Sorensen gave him a final draft, which Kennedy spent about three minutes reviewing.

Although Kennedy delivered part of the talk extemporaneously, it was one of his best speeches—a heartfelt appeal in behalf of a moral cause that included several memorable lines calling upon the country to honor its finest traditions. “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” he said. “It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities … One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free. They are not yet freed from the bonds of injustice. They are not yet freed from social and economic oppression. And this Nation, for all its hopes and all its boasts, will not be fully free until all its citizens are free … Now the time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise … The fires of frustration and discord are burning in every city, North and South, where legal remedies are not at hand … A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all … Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.”

The following week, on June 19, Kennedy requested the enactment of the most far-reaching civil rights bill in the country’s history. He presented it against the backdrop of the murder of Medgar Evers, a leading black activist in Mississippi and veteran of the D-Day invasion, who was assassinated a day after the president’s June 11 speech by a rifle shot in the back at the door to his house in front of his wife and children.

The proposed law would ensure that anyone with a sixth-grade education would have the right to vote. It also would eliminate discrimination in all places of public accommodation—hotels, restaurants, amusement facilities and retail establishments. Kennedy described the basis for such legislation as clearly consistent with the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, the 15th Amendment’s right of citizens to vote regardless of race or color, and federal control of interstate commerce. In addition to expanded powers for the attorney general to enforce court-ordered school desegregation, he also asked for an end to job discrimination and expanded funds for job training, which could help African Americans better compete for good jobs, and the creation of a federal community relations service, which could work to improve race relations. But more than moral considerations were at work in Kennedy’s decision. Bobby and the president understood that unless they now acted boldly, African Americans would lose hope that the government would ever fully support their claims to equality and would increasingly engage in violent protest. The alternative to civil rights legislation was civil strife that would injure the national well-being, embarrass the country before the world and jeopardize the Kennedy presidency.

Yet Kennedy doubted that he could persuade Congress to act and believed that a planned march on the Capitol in August might do more harm than good. White House press leaks were already discouraging the idea when the National Urban League’s Whitney Young asked Kennedy at a meeting whether newspaper reports about the president’s opposition were accurate. Kennedy responded, “We want success in the Congress, not a big show at the Capitol.” He acknowledged that civil rights demonstrations had pushed the administration and Congress into consideration of a major reform bill but said, “now we are in a new phase, the legislative phase, and results are essential. The wrong kind of demonstration at the wrong time will give those fellows [on the Hill] a chance to say that they have to prove their courage by voting against us. To get the votes we need we have, first, to oppose demonstrations which lead to violence, and, second, give Congress a fair chance to work its will.”

When other civil rights leaders at the meeting explained that the August 28 march would occur regardless of White House support, the Kennedys tried to ensure its success. Worried about an all-black demonstration, which would encourage assertions that whites had no serious interest in a comprehensive reform law, Kennedy asked Walter Reuther, head of the United Automobile Workers, to arrange substantial white participation by church and labor union members. Kennedy also worried that a small turnout would defeat march purposes, but black and white organizers answered this concern by mobilizing more than 250,000 demonstrators. To ensure that as little as possible went wrong, Bobby directed his Civil Rights Division assistant attorney general to work full time for five weeks guarding against potential mishaps such as insufficient food and toilet facilities, or the presence of police dogs, which would draw comparisons to the Birmingham demonstrations. Moreover, winning agreement for a route running from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial precluded the demonstration at the Capitol that the president feared would antagonize Congress.

The march marked a memorable moment in a century-long crusade for black equality. Its distinctive features were not violence or narrow partisanship on behalf of one group’s special interest, but rather a dignified display of faith on the part of blacks and whites that America remained the world’s last best hope of freedom and equality for all; that the fundamental promise of American life—the triumph of individualism over collectivism or racial or group identity—might yet be fulfilled. Nothing caught the spirit of the moment better, or did more to advance it, than Martin Luther King Jr.’s concluding speech in the shadow of Lincoln’s memorial. In his remarks to the massive audience, which was nearly exhausted by the long afternoon of oratory, King had spoken for five minutes from his prepared text when he extemporaneously began to preach in the familiar cadence that had helped make him so effective a voice in the movement. “I have a dream that on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood … I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low; the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together … And when this happens, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”’ As the marchers dispersed, many walked hand in hand singing the movement’s anthem:

We shall overcome, we shall overcome, We shall overcome, some day. Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe, We shall overcome some day.

Despite the success of the march, Kennedy remained uncertain about prospects for a bill of any kind. But he was genuinely impressed and moved by King’s speech. “I have a dream,” he greeted King at a White House meeting with march organizers that evening. (When King asked if the president had heard Walter Reuther’s excellent speech, which had indirectly chided Kennedy for doing more to defend freedom in Berlin than Birmingham, Kennedy replied, “Oh, I’ve heard him plenty of times.”) Almost euphoric over the size of the turnout and the well-behaved, dignified demeanor of the marchers, Roy Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph and Reuther expressed confidence that the House would pass a far-reaching bill that would put unprecedented pressure on the Senate to act. Kennedy offered a two-pronged defense of continuing caution. First, while recognizing “this doesn’t have anything to do with what we have been talking about,” he urged the organizers to exercise their substantial influence in the Negro community by putting an emphasis, “which I think the Jewish community has done, on educating their children, on making them study, making them stay in school and all the rest.” The looks of uncertainty, if not disbelief, on the faces of the civil rights leaders, toward a proposal that, at best, would take a generation to implement, moved Kennedy to follow on with a practical explanation for restraint in dealing with Congress. He read from a list prepared by Special Assistant for Congressional Relations Larry O’Brien of likely votes in the House and Senate. The dominance of negative congressmen blunted suggestions that Kennedy could win passage of anything more than a limited measure, and even that was in doubt.

Kennedy’s analysis of congressional resistance moved Randolph to ask the president to mount a “crusade” by going directly to the country for support. Kennedy countered by suggesting that the civil rights leaders pressure the Republican Party to back the fight for equal rights. He believed that the Republicans would turn a crusade by the administration into a political liability for the Democrats among white voters. And certainly bipartisan consensus would better serve a push for civil rights than a one-sided campaign by liberal Democrats. King asked if an appeal to former President Dwight D. Eisenhower might help enlist Republican backing generally, and the support of House Minority Leader Charlie Halleck in particular. Kennedy did not think that such an appeal would have any impact on Halleck, but he liked the idea of sending a secret delegation made up of religious clerics and businessmen to see Eisenhower. (Signaling his unaltered conviction that the “bomb throwers”—as Vice President Lyndon Johnson called uncompromising liberals—would do more to retard than advance a civil rights bill, Kennedy jokingly advised against including Reuther in the delegation that would see Ike.) Kennedy concluded the hour-and-10-minute meeting by promising nothing more than reports on likely votes in the House and the Senate. It was transparent to more than the civil rights leaders that Kennedy saw a compromise civil rights measure as his only chance for success.

Kennedy knew that it would take years and years to resolve race relations in the South, but he still believed that passage of a limited civil rights bill could be very helpful in buying time for the country to advance toward a peaceful solution of its greatest domestic social problem. But it was not to be. Between the end of September and the third week in November, House Democrats and Republicans—liberals and conservatives—entered into self-interested maneuvering over the administration’s civil rights proposals. He was so discouraged by late October over the bad news coming out of the House that he told Evelyn Lincoln, his secretary, that he felt like packing his bags and leaving. He also complained that the Republicans were tempted “to think that they’re never going to get very far with the Negroes anyway—so they might as well play the white game in the South.” Still, because he believed that it would be “a great disaster for us to be beaten in the House,” he made a substantial effort to arrange a legislative bargain. Kennedy’s intervention in a meeting with Democratic and Republican House leaders on October 23 produced a compromise bill that passed the Judiciary Committee by 20 to 14 on November 20. But the Rules Committee remained a problem. Larry O’Brien and Ted Sorensen asked the president how they could possibly get the bill past committee chairman Howard Smith, a Virginia segregationist who was determined to stop it from getting to the House floor in the 1963 session. Kennedy left for a political trip to Dallas on November 21, without providing an answer to their question.

The following day, the problem would be Lyndon Johnson’s.

This article was written by Robert Dallek and originally published in the August 2003 issue of American History Magazine.

For more great articles, subscribe to American History magazine today!

Featured Article

President John F. Kennedy: Eyewitness Accounts of the Events Surrounding JFK’s Assassination

The events that began unfolding around midday on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, have cast a long and lasting shadow across the intervening 40 years. In a matter of seconds a deadly deed would inflict trauma on the nation and alter the course of American history. It opened a tragedy-filled decade pocked by war, violent domestic unrest and a string of political assassinations.

An incredible 48 hours in Dallas—the president’s murder in broad daylight and the astonishing killing of his alleged assassin on live television—has spawned countless conspiracy theories. Unclear motives and a virtual labyrinth of peculiar circumstances, coincidences and seemingly inexplicable actions leave even the most rational inquisitor much room for speculation. In what is perhaps the most intensely and painstakingly examined murder in history, nearly every “fact” is fodder for debate, and every nuance leads critics to yet another “truth.” Doubts about the Warren Commission findings led to an extensive reexamination by a select congressional committee more than a decade later—whose own conclusions were hardly conclusive. The most certain fact is, for most Americans, the truth behind the events of November 22, 1963, remains shrouded in uncertainty.

However, a vast resource of eyewitness accounts offers an opportunity to experience—as nearly as possible—the realities of the moment. Recognizing human fallibility in the perception of any given event, these eyewitness accounts provide a mostly unvarnished real-time narrative from citizens, officials participating in the events and newsmen covering it. From within these accounts emerges a textured and detailed picture of those stunning hours, sometimes revealing bits of information and simple “whys” long submerged in volumes of testimony.

American History presents a chronology of those November days based almost entirely on eyewitness accounts and accompanied by searing imagery. Sworn testimony given to the Warren Commission and the magnificent oral histories collected and compiled by The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza in Dallas form the foundation of the narrative. The museum’s curator, research team and staff were invaluable in providing the most relevant transcripts, granting access to their photo archives and giving guidance.

These accounts are sometimes highly descriptive of a horrific act inflicted on men in the presence of their loved ones and shocked spectators. Eyewitnesses struggle with the incongruity of the moment; the mundane mingles with the unimaginable. Heart-rending accounts tell also of horrible personal tragedy and of extraordinary courage and strength. Our intent is to convey — as accurately as possible from the view of those who were there—a true sense of the minutes and hours of the events that consumed the nation during four days in November 1963.

|

THE DAY BEFORE

|

| In Washington, D.C. President and Mrs. Kennedy embark on a political fence-mending mission to Texas–where the Democratic Party was severely split–in preparation for the 1964 election. First stops: San Antonio, Houston and Forth Worth. Then on to Dallas and Austin. |

| In Dallas Lee Harvey Oswald, working at the Texas School Book Depository just more than a month, alters his normal routine and catches a ride with a co-worker to nearby Irving, where he spends the night with his family. He says he needs to go this day to pick up a set of curtain rods for his apartment in Dallas. |

MORNING IN FORT WORTH

Congressman Jim Wright and Texas Attorney General Waggoner Carr describe the morning in Fort Worth.

Jim Wright: I worked with what powers that be in Fort Worth to put on a good, effective breakfast meeting of the civic, business and commercial leadership of the community. We integrated it. We had representatives of the labor unions as well as of the professions and the large businesses. But even so, gosh, in those days, it was rare when the president of the United States was in your town….I said, “Look, in my hometown, I want a public meeting…we can go right outside the Texas Hotel where he’ll be spending the night, we will assemble the crowd in that big parking lot out there.”

Boy, the night before, it rained. At about 15 minutes before he was scheduled to appear, I looked out and people were already gathering in rain gear, some with umbrellas…and I thought: “Oh, what a mess. What a tragedy… what have we got him into? He’s got to get up on that flatbed trailer and speak to that crowd in the rain.” [Then] the clouds disappeared, the sun came through…bright, beautiful, sun-shining day. I thought, “The luck of the Irish.”

Waggoner Carr: There was a rally out in front of the Texas Hotel. That was followed by a breakfast at the hotel in the big dining room with a large crowd of people there, local people, and the president, after introducing Mrs. Kennedy and having a few remarks, made his speech. The president came by and shook my hand and told me how much he and Mrs. Kennedy appreciated the reception they were receiving in Texas….

OSWALD’S RIDE TO WORK

Wesley Frazier recounts the ride to the Texas School Book Depository, departing at 7:20 a.m.

Wesley Frazier: I was sitting there eating my breakfast…mother just happened to glance up and saw this man, you know, who was Lee looking in the window for me and she said, “Who is that?” And I said, “That is Lee.” He just walked around there on the carport right there close to the door and so I told her I had to go, so I went in there and brushed my teeth right quick and come through there and I just walked on out and we got in the car….When I got in the car I have a kind of habit of glancing over my shoulder and so at that time I noticed there was a package laying on the back seat…and I said, “What’s the package, Lee?” And he said, “Curtain rods,” and I said, “Oh, yes, you told me you was going to bring some today.” …so I didn’t think any more about it….

I asked him did he have fun playing with them babies and he chuckled and said he did.

JFK’s MORNING IN FORT WORTH

JFK calls Dallas Times Herald publisher James Chambers; Secret Service Agent Clint Hill, assigned to Mrs. Kennedy, describes the morning activity; Jim Wright on the flight to Dallas.

James Chambers: I was in my office about 8:15 or so, the phone rang, and it was the president. And he said, “Can you get me some Macanudo cigars?” He loved a good cigar occasionally. He says, “They don’t have any over here in Fort Worth.” And I said, “Sure.” And he said, “Well, get me about a half a dozen.” I said, “Fine.” …and got him six Macanudo cigars that I was going to give him at the luncheon….

Agent Hill: I went to the fifth floor, I believe, where the president and Mrs. Kennedy were staying in the Texas Hotel in Fort Worth, at 8:15 in the morning. President Kennedy was to go downstairs and across the street to make a speech to a gathering in a parking lot.

About 9:25 I received word from Special Agent Duncan…that the president requested Mrs. Kennedy to come to the mezzanine, where he was about to speak. I took her down to where the president was speaking, remained with her during the speech and accompanied she and the president back up to the…fifth floor…remained on that floor until we left, went downstairs, got into the motorcade, and departed the hotel for the airport to leave Fort Worth for Dallas. We were airborne approximately 11:20.

Jim Wright: President Kennedy and I and John Connally had a discussion on Air Force One….There had appeared in the Dallas News that morning a scurrilous ad calling him a traitor and other unflattering things….He had seen that. And I was irate. I thought it was a damn inhospitable thing to allow…that the paper should have screened it out. I don’t remember how the subject came up, but he was puzzled as to how to approach the Dallas News, how to be friends with them. They had written other unkind things. Mr. Dealey had written an unkind editorial about him, saying he ought to be riding Caroline’s tricycle or something like that.

ARRIVAL AT LOVE FIELD 11:40-11:45 A.M.

The presidential party touches down in Dallas at 11:40 a.m. Agent Hill and WFAA cameraman Malcolm Couch describe the activity.

Agent Hill: There was a small reception committee at the foot of the ramp, and somebody gave Mrs. Kennedy some red roses….I walked immediately to the follow-up car and placed my topcoat, which is a raincoat, in the follow-up car, returning to where the president and Mrs. Kennedy were at that time greeting a crippled lady in a wheelchair.

Malcolm Couch: When Jackie and President Kennedy got off the plane, the press was supposed to stay back about 100 feet, but we didn’t. We broke and all ran up there, and then President Kennedy headed straight for the fence and started walking along the fence shaking hands with people….I was always a little quicker than other guys. I ran in front of him, got three feet in front of him and I got the neatest shots of him shaking hands with people….

MOTORCADE INTO DOWNTOWN DALLAS 11:45 A.M.–12:29 P.M.

Motorcade recollections from the governor’s wife, Nellie Connally, in the presidential limousine; Agent Hill, directly behind the presidential limousine; and TV cameraman Couch and newspaper photographer Bob Jackson in a press pool convertible eight cars behind. Along the route are Dallas Detective Paul Bentley and spectator Glen Gatlin.

Agent Hill: Between Love Field and downtown Dallas, on the right-hand side of the street there was a group of people with a long banner which said, “Please, Mr. President, stop and shake our hands.” And the president requested the motorcade to stop, and he beckoned to the people and asked them to come and shake his hand, which they did. I jumped from the follow-up car and ran up to the left rear portion of the automobile with my back toward Mrs. Kennedy viewing those persons on the left-hand side of the street. Special Agent Ready, who was working the forward portion of the right running board, did the same thing, only on the president’s side, placed his back toward the car, and viewed the people facing the president. Agent in Charge Kellerman opened the door of the president’s car and stepped out on the street.

Detective Bentley: I was assigned to the corner of Main and Harwood, and I was at that particular location when the presidential parade passed and made a right turn onto Main. I was in plain clothes. As I first got over in front of the White Plaza Hotel the people of course were jamming the sidewalks….

Agent Hill: We didn’t really hit the crowds until we hit Main Street…where they were surging into the street. We had motorcycles running adjacent to both the presidential automobile and the follow-up car, as well as in front of the presidential automobile. Because of the crowds in the street, the president’s driver, Special Agent Greer, was running the car more to the left-hand side of the street…to keep the president as far away from the crowd as possible, and because of this the motorcycles on the left-hand side could not get past the crowd and alongside the car, and they were forced to drop back. I jumped from the follow-up car, ran up and got on top of the rear portion of the presidential automobile to be close to Mrs. Kennedy in the event that someone attempted to grab her from the crowd or throw something in the car.

Glen Gatlin: We had a very good view of the parade route. We were on the 12th floor, and so we were kind of watching [Commerce Street]. The crowds were enthusiastic, waving. Mrs. Kennedy had on a really cute pink outfit, and Gov. Connally and his wife were in the back seat. Gov. Connally always looked very, very handsome, and Kennedy, of course, was a guy that could have been a male model and sold clothes very nicely. He was doing his thing and waving, and the crowd was excited and it was just one of the best of times.

Malcolm Couch: A fella from Channel 4, KRLD…was next to me. We were both sitting on the back of the convertible as we got to the canyon of the big buildings downtown. I’ll never forget because there had been a lot of tension in Dallas politically. General [Edwin] Walker was in Dallas at the time. He was a radical right-winger. There had been some nasty statements from people in Dallas about Kennedy. As we drove along, we literally would point to buildings and say: “Boy, a sniper would sure get him from that one, what about this building over here? Perfect spot for them to get him.” That was part of the tension — that somebody would try to do something to Kennedy.

Bob Jackson: As we approached Main and Houston to make the turn, I had just unloaded my camera…one of my two cameras. It happened to be the one with the long lens because I had used it along the route more than the other one. We had prearranged for me to pass my film to a reporter who was standing at the corner [of] Main and Houston. So I unloaded the camera and put the film in an envelope. As we rounded the corner, I tossed it to Jim Featherstone, a reporter…he reached for it and the wind caught the envelope and blew it out of his hand or away from him, and he had to kind of chase it. We were kind of laughing, you know, at how he had to chase my film across the street, and we had already made the turn as this was taking place…onto Houston, which put our car directly facing the Book Depository.

Nellie Connally: We had just finished the motorcade through the downtown Dallas area. The people had been very responsive to the president and Mrs. Kennedy, and we were very pleased. In fact the receptions had been so good every place that…I could resist no longer. When we got past this area I did turn to the president and said, “Mr. President, you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you.”

SPECTATORS WAIT AT DEALEY PLAZA

The end of the downtown portion of the motorcade was Dealey Plaza. Marilyn Sitzman arrives to find her boss, Abraham Zapruder, already there; Ernest Brandt recalls the crowd’s anticipation.

Marilyn Sitzman: As I came down that street Mr. Zapruder and a couple of the other women were standing up on the [grassy knoll]. The first part of that film shows me walking up towards him. And I got up there, he turned off the camera, and we’re talking about, well, where could he stand…because by that time, there’s quite a few people gathering. And we’d go look at this place, and we’d go look at that place. We went over to where that concrete pergola was, and we decided that would be the best place because, I says: “You can get up here. You’ll be above everybody. No matter how many people are down there, you won’t have anybody blocking your view.” And so, he said…he had vertigo, though. If he got up there, he’d get dizzy. So, he says, “You’ll have to stand behind me and hold onto me.” I says, “It’s no problem at all.” So we both got up there, and I stood behind him, and I held onto him.

Ernest Brandt: Everybody was quiet and just standing there waiting until the motorcade came along. And of course, when it did, Kennedy was kind of casually waving to people, Jackie sitting next to him, looking so pretty and prim. I noticed directly behind his car, very close behind his car, was the Secret Service limousine. It was an old Cadillac where they had put running boards on the sides so that they could stand. Two men standing on each side, on the running boards, and three or four of them inside the car.

SHOTS FIRED AT THE MOTORCADE 12:30 P.M.

In the seconds after the motorcade turns left onto Elm St. and before the triple underpass, the assassin strikes. Jacqueline Kennedy in the president’s car and Vice President Lyndon Johnson two cars behind react. In addition to others in the press cars were Dallas Morning News photographer Tom Dillard and the president’s assistant press secretary, Malcolm Kilduff. Dealey Plaza eyewitnesses included Jean Lollis Hill, Malcolm Summers, Bill and Gayle Newman with their two children, and Abraham Zapruder with his Bell & Howell movie camera.

Nellie Connally: Then I don’t know how soon, it seems to me it was very soon, that I heard a noise, and not being an expert rifleman, I was not aware that it was a rifle. It was just a frightening noise, and it came from the right. I turned over my right shoulder and looked back, and saw the president as he had both hands at his neck.

Jim Wright: I heard the first shot. I thought it sounded like a rifle shot, but I couldn’t imagine that it could be a rifle shot. Then, I heard the second shot, and I thought: “It’s crazy. Someone is trying to fire a 21-gun salute with a rifle.” It was obviously a rifle shot, and obviously the shots were from the same rifle. That’s all I heard…but the timing of the third…the cadence was just off a fraction of a second enough to let me know, “Uh-oh, no, this isn’t a salute.”

Tom Dillard: …and it was loud, and I said, “They’re throwing torpedoes at him!” I guess, in my mind, those things we threw as kids that hit the sidewalk and exploded. Then, in a matter of a second and a half, another shot. Or two seconds, something like that. I said, “No, that’s rifle fire!”

Bob Jackson: We heard the first shot. Then, we heard two more shots closer together…I just looked straight up ahead of me because that’s the direction the sound came from, and I saw two black men leaning out of the window of the fifth floor, looking directly up above them. My eyes went on up to the next floor, and there was the rifle. I could see the rifle…part of the stock, and it being drawn in the window….

Tom Dillard: The third shot, I said, “My God, they’ve killed him!” Bob Jackson said, “There’s a guy with a rifle up in that window.” I said, “Where?” I had both cameras around my neck, loaded, focused, cocked…Bob says, “In that window up on that building right there, it’s that top window.” I shot a picture with the wide-angle camera. I said, “Which window?” He said, “It’s the one on the right, second from the top.” By that time, I had the 100mm camera up, shot a picture of that window….

Bob Jackson: The person behind it was not visible. There was no one standing in the window or anything looking out. He was obviously down low. Of course, I had an empty camera. I swung my camera up, too, just so I could see better with the long lens and zoomed in and no one was visible in the window. No one else in the car saw the rifle, and I don’t think I could have reacted fast enough to get a picture even if I had film in the camera. So then, the car proceeded on, rather jerkily, toward the intersection.

Jean Lollis Hill: We were standing on the curb, and I jumped to the edge of the street and yelled, “Hey, we want to take your picture!” to him. He was looking down in the seat — he and Mrs. Kennedy, and their heads were turned toward the middle of the car looking down at something in the seat, which later turned out to be the roses — and I was so afraid he was going to look the other way because there were a lot of people across the street, and we were, as far as I know, we were the only people down there in that area, and just as I yelled, “Hey!” to him, he started to bring his head up to look at me and just as he did the shot rang out. Mary took the picture and fell on the ground and of course there were more shots. She fell on the ground and grabbed my slacks and said, “Get down, they’re shooting!” And, I knew they were but I was too stunned to move….

Ernest Brandt: As soon at the limo got within view, I’m looking for Kennedy and Jackie. He was just kind of glancing at the crowd, his eyes kind of jumped along from one to another. He was kind of casually smiling…acknowledging the crowd and waving casually.

Nothing had happened by the time the limo was exactly opposite us. I was still watching Kennedy from the back. And of course, all I could see above the back seat was his shoulders, his neck, and head….I think the limousine was about 60 or 70 feet past us…it wasn’t moving real slow, but yet not real fast either…then bam! The first shot was fired, and boy, it just reverberated around the Dealey Plaza something terrible. Sounded like an elephant rifle to me. I thought it was a motorcycle backfire because there was a half a dozen of them on either side of Kennedy’s limousine. And that’s what I really thought because nothing in mind would have occurred to me that it was a rifle shot, see….I thought the first shot was a motorcycle backfire, and in conjunction with that thought, I thought he was just pretending. And that maybe he had thought, “Gee, I better duck.” You know, playfully, playing a little game in conjunction with the motorcycle backfire, but then when the second shot rang out, that canceled any thoughts I had of a motorcycle backfire. Then, in just a couple of seconds more, there was a second shot, then everybody…seemed to realize something was wrong then because Kennedy had by then already fallen over on Jackie’s shoulder.

Malcolm Summers: I was within five feet of the curb. They came around and then the first I heard was, I thought, was a firecracker…because the FBI, Secret Service people that was on the back of that car, they looked down at the ground….I think they thought it was a firecracker…I thought in my mind, well, what a heck of a joke, you know, to be playing like that. Then the car kept coming, and then the second shot rang out. And then the third…rang out. I saw Kennedy get hit. I heard Connally say, “They’re going to kill us all!” or “shoot us all.” …And then, I heard Jackie Kennedy scream out, “Oh, God! No, no, no!”

Bill Newman: We were there just a few moments… probably less than five minutes before the president’s limousine came down Main and made a right onto Houston. And I can remember hearing the crowds before seeing the cars or the motorcycle escorts. You could hear the cheers, the crowd, the noise…I felt an excitement, you know, because the president was getting close. I can remember seeing the car turn right onto Houston Street off of Main, going the one short block and turning left on Elm. When he was probably 150 or 200 feet away the first two shots rang out, and it was like a “Boom…Boom.”

Gayle Newman: I had no idea that it was gunfire. The first two noises sounded like firecrackers, and I think both of us…had the same impression…that’s really in bad taste, you know. Throwing firecrackers at the president’s car. But he seemed to be going along with the joke, you know. He sort of put his hands up and sort of was looking around the crowd, and you know, thoughts just sort of flash through your mind. And we thought…well, I did…boy, he’s got a good sense of humor, you know…to react like that.

Bill Newman: He straightened up and brought both arms up….But, as the car got closer to us, I felt that something was wrong. I remember seeing a bewildered look on President Kennedy’s face, and I can remember seeing Gov. Connally, and he was sort of crouched down and holding himself. I can remember his protruding eyes. I mean, his eyes looked like they were bugging out like he was in a state of shock. I could see the blood on his shirt. Just as all of this is going through my mind, the car passed directly in front of us.

Jim Wright: As we turned, heading west…we looked and saw pandemonium in the cars and Jacqueline Kennedy on her knees in the back seat, looking out behind, and we couldn’t imagine what was happening. Then, the car shot forward….As we passed the crowd on the grassy knoll, the look of sheer horror in their faces told me that they had just witnessed a traumatic event.

Marilyn Sitzman: When they started to make their first turn…turning into the street, he [Zapruder] said, “OK, here we go.” …That’s when I remember he started actually doing the filming. They turned the corner and they started coming down…and the first thing I remember hearing was what I thought was firecrackers because Kennedy threw his hands up, and I heard “bang, bang.” There could have been a third “bang,” I can’t swear to that one. But I know there were two “bangs” very close together, and I thought they were firecrackers because his arms were going into the air, and it was way off to my left and above. I’m just kind of like…”what a stupid thing to throw firecrackers,” and as they came down…the last shot that we heard was right in front of us and it was like the same sound…far off and to the left…but I saw his head open up….So, of course, by this time I knew it wasn’t firecrackers.

Abraham Zapruder: As the car came in line almost — I believe it was almost in line, I was standing up here and I was shooting through a telephoto lens….I heard the first shot, and I saw the president lean over and grab himself. Leaning toward the side of Jacqueline. For a moment I thought it was, you know, like you say, “Oh, he got me!” when you hear a shot—you’ve heard these expressions and then I saw—I don’t believe the president is going to make jokes like this, but before I had a chance to organize my mind, I heard a second shot and then I saw his head opened up and the blood and everything came out. I can hardly talk about it.

Agent Hill: As we came out of the curve and began to straighten up, I was viewing the area which looked to be a park. There were people scattered throughout the entire park. And I heard a noise from my right rear, which to me seemed to be a firecracker. I immediately looked to my right and, in so doing, my eyes had to cross the presidential limousine, and I saw President Kennedy grab at himself and lurch forward and to the left.

Malcom Kilduff: I heard this first noise, and Merriman Smith said, “What the hell was that?” And I said, “Well, it sounded to me like a firecracker.” And then, the second shot…by that time, I had noticed that Clint Hill…had jumped off the Secret Service follow-up car and was running towards the president’s car.

Jacqueline Kennedy: You know, there is always noise in a motorcade, and there are always motorcycles beside us, a lot of them backfiring. So I was looking to the left. I guess there was a noise, but it didn’t seem like any different noise really because there is so much noise, motorcycles and things. But then suddenly Gov. Connally was yelling, “Oh! No, no, no!”

Agent Hill: I jumped from the car, realizing that something was wrong, ran to the presidential limousine. Just about as I reached it, there was another sound, which was different than the first sound. I think I described it in my statement as though someone was shooting a revolver into a hard object — it seemed to have some type of an echo. I put my right foot on the left rear step of the automobile, and I had a hold of the handgrip, when the car lurched forward. I lost my footing, and I had to run about three or four more steps before I could get back up in the car.

Gayle Newman: As the car came closer…as it got directly in front of us, the third shot rang out and the side of his head was hit, and you saw bits of red flashing up and then some white matter come out of his head, and Mrs. Kennedy screamed, “Oh my God, no! They’ve shot Jack!”

Bill Newman: I remember a flash of white and then a flash of red, and President Kennedy going over across the car seat into Mrs. Kennedy’s lap and her hollering out, “Oh my God, no! They’ve shot Jack!” And I can remember her going back. I thought she was trying to get out of the car. I turned and said, “That’s it, Gayle! Hit the ground!” So, we hit the ground, covered our two children, thinking that we were in danger….

Jacqueline Kennedy: I was looking…to the left, and I heard these terrible noises. And my husband never made any sound. So I turned to the right. And all I remember is seeing my husband, he had this sort of quizzical look on his face, and his hand was up, it must have been his left hand. And just as I turned and looked at him, I could see a piece of his skull and I remember it was flesh colored. I remember thinking he just looked as if he had a slight headache. And I just remember seeing that. No blood or anything. And then he sort of…put his hand to his forehead and fell in my lap. And then I just remember falling on him and saying, “Oh, no, no, no!” I mean: “Oh, my God! They have shot my husband!” And “I love you, Jack!” I remember I was shouting. And just being down in the car with his head in my lap. And it just seemed an eternity.

You know, then, there were pictures later on of me climbing out the back. But I don’t remember that at all.

Malcolm Kilduff: And then I noticed that the Secret Service car and the president’s car had started to speed up. So we sped up in the pool car….This would be a normal operating procedure, to get the hell out of there in a big hurry. You know, it never even occurred to me that the president had been shot.

Lyndon Johnson: After we had proceeded a short way down Elm Street, I heard a sharp report. The crowd at this point had become somewhat spotty. The vice-presidential car was then about three car lengths behind President Kennedy’s car, with the presidential follow-up car intervening.