‘Devil Bill’ was a grifter, a bigamist, and a pain in his son’s behind

HE’D RIDE INTO TOWN on a fancy rig pulled by fine horses. He’d draw a crowd by sticking a clay pipe into a manikin’s mouth, striding 200 paces, raising his rifle, and shooting the pipe out of the dummy’s yap. Then he’d whip out a $10 bill and offer it to anyone able to duplicate his feat. Few people could.

That’s how the bearded stranger sporting flashy clothes and gold rings got folks’ attention in small upstate New York towns in the decades before the Civil War. Attention gotten, he’d introduce himself as an “herbal doctor” or a “botanic physician” and peddle bottles of his home-brewed patent medicine. The stuff could cure any ailment, he promised—even cancer. Sometimes he flogged purple pills he said were excellent for stomach complaints. However, he warned, a pregnant woman should never take those tablets because they could cause her to miscarry—a coded “warning” designed to appeal to the unhappily expectant.

The medicines were worthless, the pills were purple berries, and the “doctor” was an uneducated flimflam man with two identities. Sometimes he went by “Dr. William Levingston,” sometimes “Dr. William Rockefeller.” His neighbors called him “Devil Bill.”

He was born William Avery Rockefeller in Granger, New York, in 1810, son of a poor farmer with a fondness for booze. Tall and strong, Devil Bill was an excellent hunter, fisherman, storyteller, and fiddle player. But he had no interest in farming or any other form of hard work, so in his 20s he left home to peddle trinkets and miracle cures. Sometimes he carried a slate reading “I am deaf and dumb,” so he could con the softhearted while eavesdropping on gossip spread by folks who thought he couldn’t hear.

In 1836, Devil Bill was fleecing rubes around Moravia, New York, when he courted a local girl named Nancy Brown. Nancy was beautiful but penniless, so his eye turned to Eliza Davison, a redhead with a prosperous father. Bill married Eliza in 1837, gaining a wife and a $500 dowry. They settled in nearby Richford and, to ease Eliza’s burdens, Bill hired a maid—Nancy Brown. Within two years, Eliza and Nancy each had borne two Rockefeller babies.

Wives gripe when maids bear husbands’ spawn and Eliza sent Nancy Brown and her bastards packing. But that didn’t end Mrs. R’s troubles. Without warning, her husband frequently disappeared, sometimes for months, traveling the countryside running scams. He’d return, wearing diamonds and flashing a stack of greenbacks. Making a show of paying Eliza’s grocery tab with big bills, Devil Bill would invite neighbors to a feast and regale them with tales of his adventures. “He would dress up like a prince and keep everybody wondering,” a neighbor recalled. “He laughed a great deal and enjoyed the speculation he caused.”

That speculation focused on how Devil Bill acquired his riches. Was it all from dubious doctoring? Rumors that he led a ring of horse thieves gained credence when two Rockefeller cronies were convicted of stealing nags. One thief’s son swore later that Devil Bill was the ringleader. “Rockefeller was too smart to be caught,” he said. “He ruined my father and then left him in the lurch.”

No doubt a scoundrel on the road, Rockefeller seemed a fine fellow back home. He ran a prosperous lumber business, eschewed booze, and

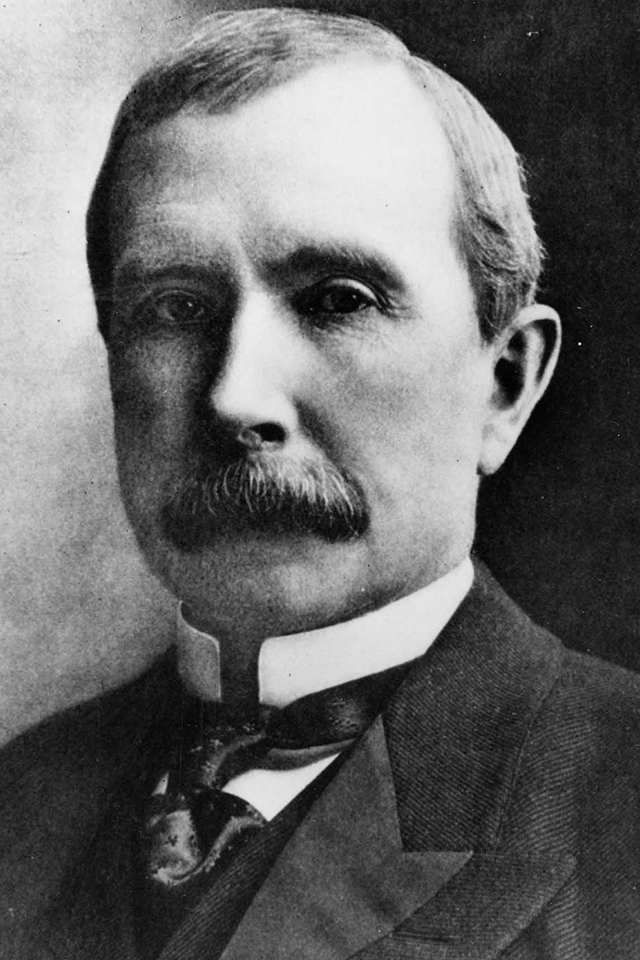

supported his six children with Eliza. But he did use unorthodox methods of educating his kids. He propped eldest son John on a high chair and told the boy to jump into his arms. Several times he caught the child, but then stepped back and let the boy crash to the floor. “Remember,” father told son. “Never trust anyone completely, not even me.” To teach his sons about business, he swindled them. “I trade with the boys and skin ’em,” he told a neighbor. “I want to make ’em sharp.” This eccentric education paid off: his eldest son, John D. Rockefeller, later became the richest man in the world. “To my father, I owe a great debt,” John D. once said. “He taught me the principles and methods of business.”

Devil Bill’s restless streak kept him roving. On one trip, he was indicted for rape, though never prosecuted. Roaming Canada in 1852, Bill, 42, introduced himself to teenaged Margaret Allen as Dr. William Levingston. The two wed. Now the man with two names had two wives—Eliza in New York and Margaret in Illinois. But he frequently avoided both of them, preferring to ramble as far west as the Dakotas, swindling the sick. In the 1870s, he took on an apprentice, Charles Johnson, and taught him the art of quackery. “He made me pay him $1,000 for my tuition,” Johnson said, “which illustrates his shrewdness.”

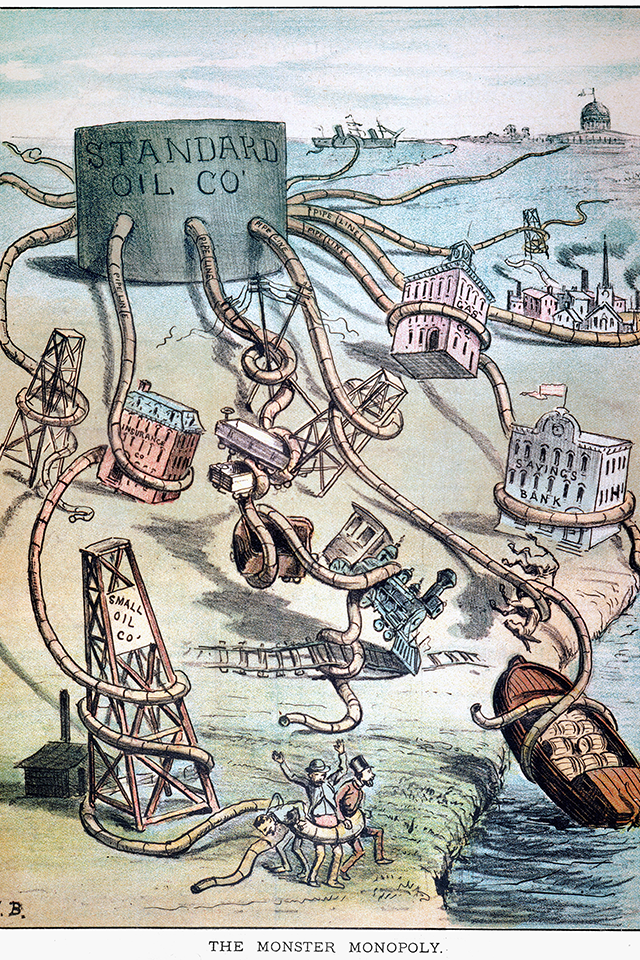

While Devil Bill was working his schemes, son John was building America’s biggest monopoly, the Standard Oil Company, aka “the Octopus,” and becoming the world’s first billionaire. John’s techniques were more sophisticated than Dad’s but not necessarily more ethical. A black-suited Baptist of ostentatious rectitude, John blanched at his flamboyant father’s bigamy, determined to hide his father’s sins. In 1881, he bought the old man a ranch in North Dakota, far from nosy reporters. In 1889, when Eliza Rockefeller died, John floated the falsehood that his mother had been a widow.

But Devil Bill was still alive and tricking. He’d occasionally appear unannounced at one or another of John’s residences to entertain the grandkids by shooting his rifle, playing the fiddle, and telling wild stories. Visiting in 1902, Devil Bill—92, asthmatic, nearly blind—took

delight in embarrassing his son. “Here comes Johnnie,” he announced to a group of guests. “I suppose he is a good Baptist but look out how you trade with him.” When he started telling dirty jokes, John tried to slip away, but his father grabbed him and forced the blushing billionaire to listen.

In 1906—as Devil Bill lay dying in the Freeport, Illinois, home he sometimes shared with wife Margaret—the old man had a mysterious visitor who arrived in town by private railcar. The caller would enter Bill’s room only when nobody else was present.

Two years after Devil Bill died, the New York World printed the story John D. Rockefeller had been hiding for decades. Headlined “Secret Double Life of Rockefeller’s Father Revealed by The World,” the article recounted lurid tales of Bill’s adultery, bigamy, quackery, and chicanery. John D. Rockefeller declined to comment.