As union soldiers marched mile after mile or sat idle waiting for new orders, they filled the air with choruses about John Brown. The song originated as a tribute to a common soldier, but it quickly evolved into a popular war tune immortalizing a different man–the John Brown whose 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry and subsequent hanging ignited sectional conflict.

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul’s marching on!

Glory Hally, Hallelujah!

His soul’s marching on!

He’s gone to be a soldier in the army of the Lord,

His soul’s marching on!

Brown’s execution also threw his large family into turmoil. He left behind a total of eight children, four by his widow Mary Ann Day Brown: Salmon, Annie, Sarah and Ellen; and four by his first wife, Dianthe Lusk: John Jr., Jason, Owen and Ruth. Three of his sons–Watson, Oliver and Owen–had participated directly in the assault, and only Owen escaped with his life.

|

| John Brown in 1859, the year his raid on Harpers Ferry forever changed the lives of his wife and children. (Library of Congress) |

While many in the North sang John Brown’s praises after his execution, the South branded him a traitor and a murderer. His body lay mouldering in the grave for more than a year before the Civil War started, yet he was still a famous figure and his name stirred controversy. The Brown family could not escape attention. ‘Following the dark days at Harpers Ferry, the suffering of mother and the family was intense,’ Salmon recalled in later years. ‘The passing years did not heal the horrible wounds made by the country father had tried so hard to help to a plane of higher living.’

John Brown had foreseen the suffering that would befall his family. From his jail cell in 1859, he wrote to his wife, asking Mary not to visit him, explaining that the trip would use up ‘the scanty means’ she had. ‘For let me tell you that the sympathy that is now aroused in your behalf may not always follow you,’ he added. Brown’s words proved only partially prophetic. Although often met with scorn, the Browns also continued to attract many sympathetic supporters. But no matter what the response, they always drew attention. Never again were their lives tranquil and private.

The immediate aftermath of the Harpers Ferry raid and trial proved especially difficult for son Owen, daughter Annie and daughter-in-law Martha because they had been involved in the incident. Owen escaped during the attack and remained in hiding for months. In January 1860, his sister Ruth wrote, ‘Owen is wandering somewhere, & our anxiety for him is very great.’

Annie, 15, and Martha, 17, had lived with the raiders at the Kennedy farm near Harpers Ferry, although the girls had left days before the attack. Annie was nearly driven insane by the news that 10 men, including her brothers Watson and Oliver, had been killed and her father and four others had been captured. ‘She did not shed a tear for several days after hearing the news but looked wild and heart-broken,’ recalled Ruth. Annie later wrote: ‘That is a time that I do not like to think of or speak of….I do not think I have ever fully recovered from the mental shock I received then.’ She explained, ‘The honor and glory that some saw in their work did not fill the aching void that was left in my heart after losing so many loved ones and friends.’

Illness followed the mental anguish Annie suffered. Shortly after her father’s burial, her mother, Mary, and Salmon’s wife, Abigail, also became ill. The only healthy woman in the house was Oliver’s wife, Martha–and she was six months pregnant. Despite her condition, Martha did all the chores and nursing.

Only 16 when she married Oliver, Martha sympathized with his desire to abolish slavery, even risking her life to join him at the Kennedy farm. When she returned to the Brown family farm in North Elba, N.Y., news of Oliver’s death left her bereft. Her only solace was that she still carried their child. Although the strain of grief, pregnancy and her increased household duties made her weak and ill, she still managed to give birth. But the baby lived only a few days, and Martha’s health declined rapidly after that. She died just four weeks from the day her baby was born. The Weekly Anglo-African of April 14, 1860, reported Martha’s death, writing, ‘She was so anxious to depart, that it seemed almost selfish to wish her to stay; yet she was so good, kind and benevolent in her disposition, that no one who knew her could help loving her and mourning her loss.’ Annie later called Martha ‘one of the unknown heroines that this world passes by unheeded.’

|

| Daughters Annie (left) and Sarah were photographed with their mother, Mary Ann Day Brown, about 1851. (Library of Congress) |

John Brown sympathizers tried to help the family of the martyr to the abolitionist cause. Money and words of support came from blacks and whites alike in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland and other Northern cities. Prominent abolitionists such as Rebecca Spring sent money and provided schooling for 16-year-old Annie and her 13-year-old sister, Sarah.

Mary sent the two girls to Concord, Mass., to attend Frank Sanborn’s private school early in 1860. Still in shock, Annie had a tough time adjusting. ‘My memory was affected so I could not commit school books,’ she said. ‘The harder I studied the less I seemed to know.’ Sometimes she would lock herself in her room ‘and lay and roll on the floor in the agony of a tearless grief for hours at a time.’

Reformer Bronson Alcott hosted Mary Brown and Watson’s widow and son, Isabelle and Frederick, as guests of honor at a tea at his home in Concord. A throng of people gathered outside, without invitations, straining to see members of John Brown’s family during the gathering. ‘The two pale women [Mary and Isabelle] sat silent and serene through the clatter,’ wrote Louisa May Alcott, Bronson’s daughter. She depicted Mary as ‘a tall, stout woman, plain, but with a strong, good face, and a natural dignity that showed she was something better than a ‘lady,’ though she did drink out of her saucer and used the plainest speech.’ The future author of Little Women, Louisa scrutinized Isabelle, too, writing that she ‘had such a patient, heartbroken face, it was a whole Harpers Ferry tragedy in a look.’ As for baby Frederick, he was ‘a fair, heroic-looking baby, with a fine head, and serious eyes that look about him as if saying, ‘I am a Brown! Are these friends or enemies?” The multitude of guests praised and kissed him, and he bore it ‘like a little king.’

In Ohio, John Brown Jr. complained of the great expense of handling the crowds that came to visit him. ‘Our house has been like a well-patronized Hotel,’ he said. ‘Very many coming to see us from motives of mere curiosity.’ Others directed their curiosity and adulation toward the farm in North Elba, John Brown’s burial site. As Brown had strongly believed in the Declaration of Independence and its advocacy of freedom for all men, July 4 became a day of pilgrimage for antislavery advocates. In 1860 more than 2,000 people gathered at his grave.

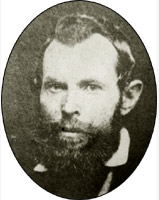

|

|

|

| Of the three sons who participated in the Harpers Ferry attack, Watson (left) was mortally wounded, as was Oliver (middle). Owen (right) managed to escape. (Library of Congress) | ||

After the war began, the Brown family remained committed to the abolition of slavery but deplored the bloodshed. ‘Oh what a dreadful war that is,’ Mary wrote. ‘When I read of so much suffering I feel to cry out how long Oh Lord how long shall this people continue in their sins and the innocent have to suffer with the guilty.’

Salmon attempted to help the family financially by joining the Union Army in early 1862. Colonel John Fairman of New York City needed men to fill Company K of the 96th New York Regiment. He came to North Elba and asked Salmon to join, promising him a lieutenant’s commission. However, when the other officers in the regiment found out that Salmon was the son of John Brown, they balked. The officers drafted and signed a petition stating that they were not against Salmon ‘as a man or citizen,’ but they did not wish ‘to associate with a man having the notoriety that said Brown has in our country.’ They feared that his presence would bring additional risks, and asked Colonel Fairman to remove Salmon as a member of the regiment. Salmon chose to resign rather than cause trouble. But newspapers picked up and spread the story. The Liberator actually printed a list of the petitioners, so that the names of those who had scorned the son of John Brown would be ‘handed down in history!’

Forced to resign from the Army, Salmon did not want to stand by and watch the war. He headed for California. As Salmon was the only son helping at the North Elba farm, his departure would have made it difficult for Mary to remain. But Mary also wanted to remove her daughters from the public attention that dogged them throughout New York and New England. She thought that going with Salmon ‘would give Annie and Sarah a chance to do something for themselves in a new country that they cannot have here.’ Furthermore, Mary thought she could keep the greater part of her family together by moving West. But Annie had notions of her own.

Annie had spent enough time at school and felt ready to serve the abolitionist cause again. Months earlier, she had sent a letter to Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison seeking a teaching position among the newly freed blacks. ‘Being desirous of going South to Port Royal, Hilton Head, or elsewhere to engage in teaching ‘Contrabands’ [freed slaves] and not knowing where to go, or what to do,’ she wrote, ‘I thought I would apply to you for information on the subject. Some time since there was a call for such teachers, and I believe I could fill that place.’

Ignoring the potential danger, Annie found a position in October 1863 at the contraband schools in Norfolk and Portsmouth, Va. She also attended Sunday school in former Virginia governor Henry A. Wise’s mansion on the Elizabeth River (Wise was then off serving as a Confederate brigadier). She noted that being welcomed into the house of the man responsible for hanging her father seemed inexplicable to her.

After six months in Virginia, Annie joined her mother, sisters Sarah and Ellen, brother Salmon and his family in Iowa and all headed west in a covered wagon. They crossed the prairies, following the Mormon Trail to beyond Fort Kearny, Neb. After hearing stories of Indian troubles, the Browns joined a large wagon train. At one point, a band of 250 Sioux warriors approached and rode in among the wagons but left when members of the train brandished their weapons at the intruders.

Worse troubles started when a group of Confederate sympathizers joined the train and discovered John Brown’s family. The family suspected the newcomers of attacking their sheep. Annie wrote, ‘Little Dick and the two best ewes, we have reason to believe, were poisoned by a rebel.’ Then the Browns discovered that the Rebels plotted to kill Salmon, and perhaps the rest of the family, too.

Newspapers, meanwhile, still found the Brown family a story. The New York Tribune of September 22, 1864, reported, ‘There is a painful rumor, not yet confirmed…that they were pursued by Missouri guerrillas, captured, robbed, and murdered.’ It was only a rumor. The Browns had managed to safely reach the Union post at Soda Springs, Idaho, just three hours in front of their pursuers. Soldiers traveled with the Browns for the next 200 miles to Nevada. From there, the family followed the California Trail to Humboldt City and entered northern California.

One concern must have occupied the minds of the Browns once they left home: What did the West think of John Brown? Was he martyr or madman to the people of California? The answer came unambiguously. When the party reached the tollgate outside Red Bluff, a collector extended his hand for money. ‘And what might be your name?’ he asked gruffly. When he discovered that they were John Brown’s family, he handed back their money, removed his hat and said, ‘Pass.’ The people of Red Bluff received them warmly, too. ‘We were given a sack of flour and other groceries, and I was given a pair of shoes and cloth for a dress,’ recalled Salmon’s wife, Abigail. ‘Mr. Brown got a job at once grubbing out young oaks for forty dollars. He did the job in eight days and we felt rich. How I loved California.’

Salmon had hoped to prosper from his full-blooded Spanish Merino sheep, but only two survived the trip. ‘Can’t say what he will do,’ wrote Annie. ‘He talks of buying a small place, on time, and raising a few sheep, grapes, fruit, etc.’ Salmon would eventually run a farm and raise a big family, but he would commit suicide in 1919 for reasons not thought to be connected to Harpers Ferry.

Mary and her youngest child, Ellen, age 11, planned to live in Red Bluff, a community of about 2,000 people located on the Sacramento River. The townspeople collected money to build a little cottage for them. The editor of Red Bluff’s newspaper stated, ‘If every man, woman, and child in California who has hummed ‘John Brown’s Body Lies Mouldering in the Grave’ will throw in a dime, his family will have a home.’ The dimes and dollars came forward. Even the governor of California helped raise funds. In January 1866, the house was finished and turned over to Mary Brown.

In the meantime, the townspeople came to know the Brown family. Mary served as a nurse to the sick and was thought of as a ‘clever, sensible Christian lady.’ Annie and Sarah taught school and were regarded as intelligent and well-educated.Annie had been eager to find a teaching job that suited her abolitionist views. She heard there was a school near Red Bluff, on Coyote Creek, that needed help. Because it was a school for blacks, including boarding arrangements for the teacher with a black family, it had attracted no applicants. Annie volunteered. When asked why she would do such a strange thing, Annie replied, ‘Am I not John Brown’s daughter?’

Yet the weight of being John Brown’s daughter grew too heavy after Annie married and started her own family. She decided ‘to shut the past away.’ She said she related so little of the old days to her children ‘that they had not even known what Browns they were.’ She felt it would be a ‘disadvantage to them to be known as J.B.’s grandchildren.’

In 1892, after her children were grown, Annie was asked to be part of a Harpers Ferry exhibit at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. She declined, explaining that she was a relic of John Brown’s raid but that it was ‘not something to boast of or exhibit myself for….I do not want to be placed on exhibition with other relics and curios.’

Eighty years after the Harpers Ferry raid, descendants of John Brown did want to preserve the Brown legacy. In the 1970s, Salmon’s daughter, Nell Brown Groves, said: ‘I’m very proud of what John Brown did. Slavery was wrong. What he stood for was right–he figured force against force.’ Groves, listed in Who’s Who Among American Women for her musical and artistic accomplishments, has tried to perpetuate the name. ‘We’re proud of what he did,’ she said, ‘and we’re loyal to the cause.’

This article was written by Sandra Weber and originally published in the February 2005 issue of Civil War Times Magazine.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!