Charles M. Russell and Joe De Yong had much in common. Both came from the St. Louis area. Both wanted to cowboy. Both wound up in Montana. And both wanted to paint the West as it was, with painstaking attention to detail. It’s little wonder De Yong became Russell’s protégé. But De Yong also left his own legacy.

“De Yong was not only an accomplished artist and illustrator himself, he also played an important role in shaping the visual history of the Western as we know it,” says Emily Crawford Wilson, curator of the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, Mont. “After Russell’s death, De Yong worked as a film consultant on many early Western movies that were the cornerstones of the Western genre. His wellspring of visual knowledge…literally shaped that distinct brand of American visual culture for decades to come.” William Reynolds gives the artist his due in the illustrated biography Joe De Yong: A Life in the West. “I was not going to let him be forgotten,” Reynolds says.

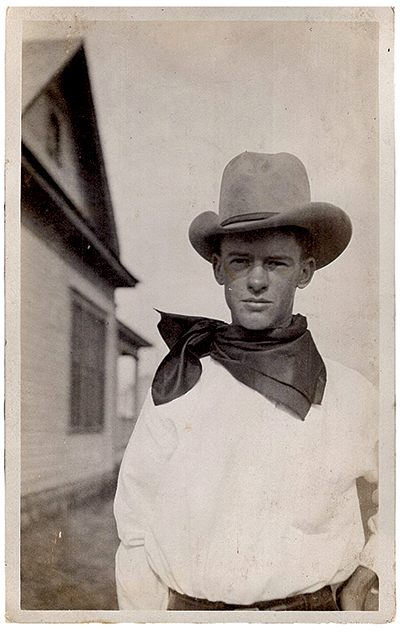

Born in Webster Groves, Mo., in 1894, De Yong worked on area ranches as a youngster, sketching horses and cowboys in his downtime. As a teen he got work as an extra on a Tom Mix Western filmed in the area, became interested in motion pictures and took off to Arizona for more movie work. Then fate stepped in. A 1913 bout with cerebral meningitis left the 19-year-old wholly deaf. “Deafness was considered more than a disability,” Reynolds says. “You were considered a little less than human in society.”

But De Yong didn’t let that stop him. Soon after he struck up a correspondence with Russell, and in 1916 he moved to Great Falls to work in Russell’s studio. They got along just fine. “Russell was not the biggest conversationalist unless he was drinking with his pals,” Reynolds says. “When he was working on art, he never talked.” Russell and De Yong used sign language to communicate while painting or catching the latest silent movies in town. “They would hand-talk back and forth and criticize things and talk about horses. So there was a very strong bond because of the fact that they communicated with each other in a way that was unique to the two of them.”

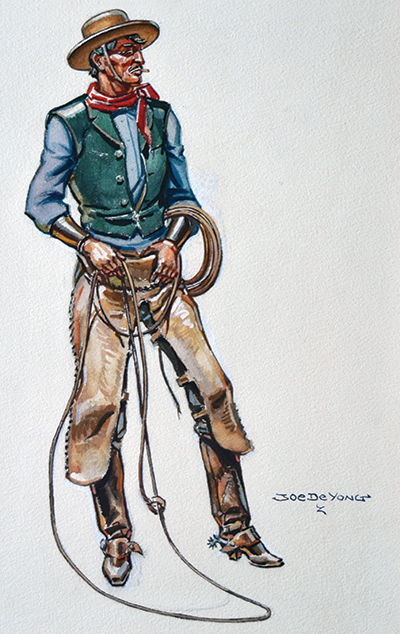

When Russell’s demands kept him from illustrating magazines and books, wife Nancy recommended De Yong to the publishers. “It’s pretty obvious De Yong couldn’t carry water compared to Russell’s work,” Reynolds admits. “His paintings did not have the palette Russell had. Russell had a natural ability to bring colors to light. But De Yong’s real strength were his illustrations, to the point where he could finish them really quickly. He’s much more of an illustrator than a fine artist.” Indeed, it was De Yong’s talent as an illustrator that finally led him full circle—to stints as a Hollywood designer and historical consultant.

In the wake of Russell’s death De Yong was living in Santa Barbara, Calif., when director Cecil B. DeMille hired him to work on the 1936 Gary Cooper film The Plainsman. “They needed someone who could do set design, scenic design and costume design who was authentic,” Reynolds says. “DeMille was as big of an authenticity freak as De Yong.”

By the time of his own death in 1975 De Yong had rendered more than 1,500 costume illustrations and worked on 20-plus films, including Union Pacific (1939), North West Mounted Police (1940), Buffalo Bill (1944), Red River (1948) and Shane (1953), in which De Yong paid visual tribute to Russell. “The scenes with Jack Palance in that raised-entry saloon are right out of a Charlie Russell painting,” Reynolds explains. “In Without Knocking was literally the influence for that.…There are so many paintings that influenced De Yong in translating it. At the same time he was being true to his mentor to continue in the modern medium of film with what Russell had tried to do with paintings.”

Russell certainly helped De Yong, but De Yong helped Russell, too. “De Yong allowed Russell to become a teacher,” Wilson says. “By correcting his work, painting alongside him, advising him on matters of Western life and artistic enterprise and technique, Russell was articulating and codifying his own artistic practice. And by passing on his knowledge to De Yong, Russell helped perpetuate and grow his own legacy.” WW