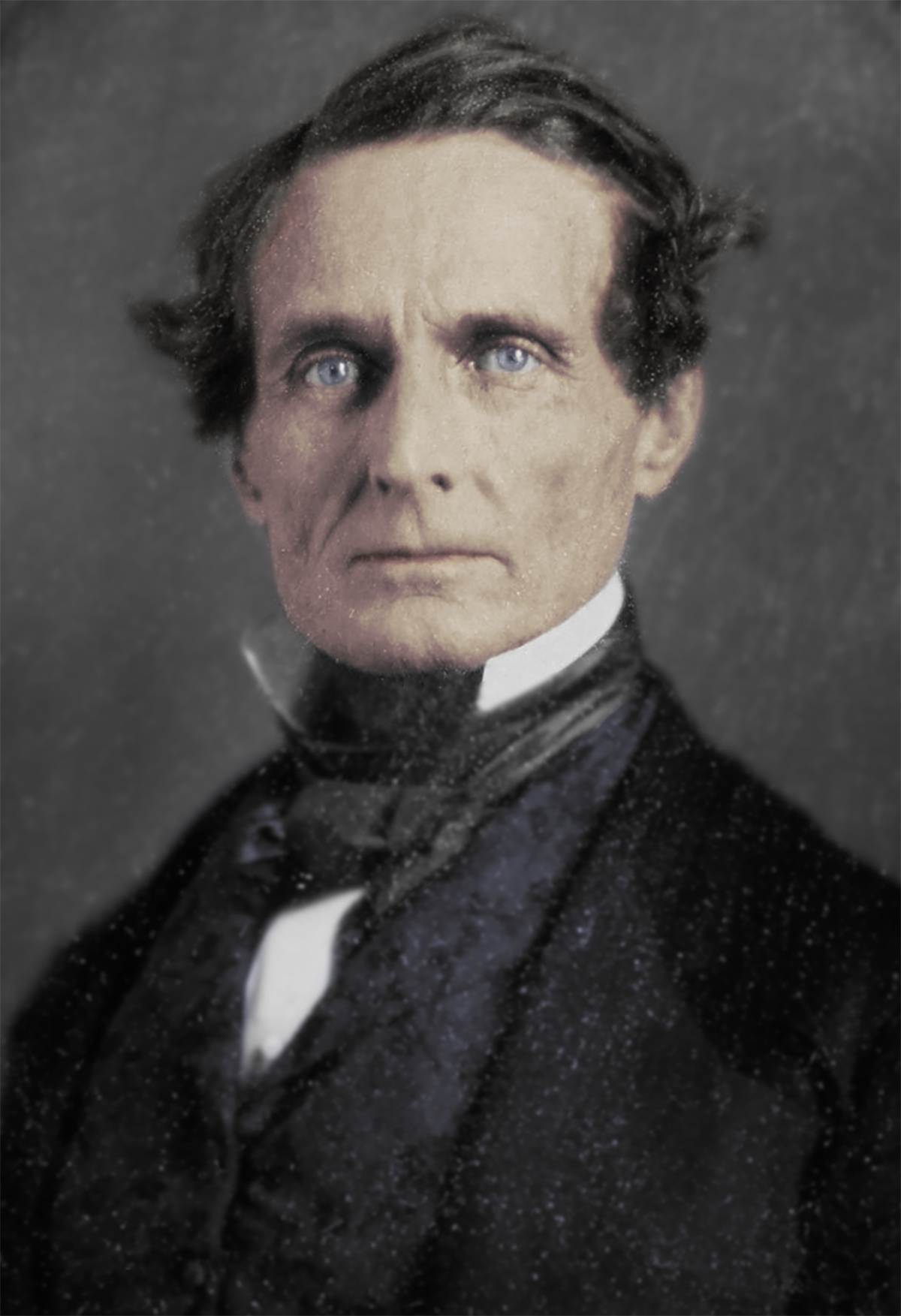

Jefferson Davis Facts

Born

June 3, 1808, Fairview, Kentucky

Died

December 6, 1889, New Orleans, Louisiana

Office Held

President Of Confederate States

February 18, 1861 – May 10, 1865

Military Rank

Colonel

Wars Fought

Black Hawk War

Mexican-American War

Jefferson Davis Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Jefferson Davis

» See all Jefferson Davis Articles

Jefferson Davis summary: Jefferson Davis was one of ten children born to his parents, Jane and Samuel Davis. He grew up in Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi. His education included the Wilkinson Academy and Catholic School St. Thomas at St. Rose Priory. He continued his studies at Jefferson College at Washington, Mississippi and at Transylvania University at Lexington, Kentucky. In June of 1828, he graduated from West Point.

Jefferson Davis Leaves The Military To Get Married

He served under Zachary Taylor and fell in love with Taylor’s daughter. Taylor refused to give his daughter’s hand in marriage to a military man because it was not a life he wished for his child. Davis resigned from the military, giving up his commission to marry Sarah Taylor. They became plantation owners but Sarah caught malaria and died three months after the wedding.

Davis Goes To War

Eventually he married again and had six children. When the Mexican-American war began in 1846, Davis became Colonel of the Mississippi Rifles volunteers. He gained military experience at the siege of Monterrey and at the Battle of Buena Vista.

Secession And Davis’ Rise To Presidency

In 1861, South Carolina and Mississippi seceded from the Union and Davis left the Senate to return to Mississippi. On Feb. 22, 1862, Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the President of the Confederate States. He decided that General Robert E. Lee should command the Army of Northern Virginia, which was a very successful move at the time.

Davis After The Civil War

At war’s end, Jefferson Davis was captured in Irwin County, Georgia and became a prisoner at Ft. Monroe on May 19, 1865. He was tried and found guilty of treason. After two years, he was released from prison for $100,000 bail. He died at 81 years of age.

Articles Featuring Jefferson Davis From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

The Dahlgren Papers Revisited

In the winter 1999 issue of Columbiad, James M. McPherson reviewed Duane Schultz’s The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War and took note of an article of mine on the same subject that appeared more or less simultaneously in MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. In his review, McPherson pointed out that Duane Schultz and I ‘come down on opposite sides’ regarding the authenticity of the so-called Dahlgren papers, the documents at the core of the ‘Dahlgren affair,’ as Schultz terms it. After balancing the two sides in the case, McPherson offered the Solomonic judgment that ‘the genuineness of the Dahlgren papers is contestable….’1

I will make a case for the genuineness of the Dahlgren papers–and make it strongly enough to remove that ‘contestable’ label. First, however, it is necessary to sketch in the background and the details of what came to be called the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid. The raid itself was an utter failure and would merit nothing more than a footnote in Civil War history books except for the intrigue that occurred in its aftermath.

During the bitter winter of 1863-64, while the armies of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade and General Robert E. Lee occupied winter quarters on the opposite sides of the Rapidan River in northern Virginia, concern deepened in Washington for the welfare of Union prisoners being held in Richmond. Prisoner exchanges were floundering because of the Confederacy’s refusal to exchange captured black soldiers. The Federal enlisted men penned in the prison camp on Belle Isle in the James River and the Union officers incarcerated in Libby Prison consequently soon began to suffer from overcrowding and its related effects. By one estimate, as many as fifteen hundred prisoners were dying each month from disease, hunger, or exposure. The Lincoln administration welcomed anyone with ideas for relieving this situation. The first to offer a plan and gain a hearing was the imaginative but inept Ben Butler.

Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s command, based at Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, was the Union force closest to the Confederate capital. Butler advocated launching a surprise cavalry raid to break into Richmond and free the prisoners. He designed his raid to accomplish even more, however. Once in the city, his troopers would destroy prime military targets such as the Tredegar Iron Works and capture President Jefferson Davis and any other Confederate worthies they could find. Butler visited Washington and had his plan approved by President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. The Rebels, however, were forewarned of the scheme, and on February 7, 1864, they turned back Butler’s troopers shortly after they started forward. As it turned out, the sole aspect of the Butler raid worth remembering was its plan for carrying off President Davis.2

It took Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick less than a week to pick up the torch from Butler’s palsied hand. Nine months earlier, during the Chancellorsville campaign, then-Colonel Kilpatrick led his brigade to the gates of Richmond during a Federal cavalry operation aimed at cutting General Lee’s railroad supply line. That operation accomplished very little overall, but Kilpatrick’s adventure elicited much comment. Now commanding the Third Division of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, Kilpatrick determined to put this raiding experience to good use by leading a coup de main against the Confederate capital and freeing the Union prisoners there.

Judson Kilpatrick was ruthless, reckless, and inordinately ambitious. His nickname, ‘Kill-Cavalry,’ was applied in reference to the body count among his own troopers as well as the enemy’s. Probably with the assistance of at least one Republican senator friendly to his cause, Kilpatrick found himself invited to the White House on February 12 to present his case for a raid on Richmond. He consulted with no one in the chain of command in obtaining the invitation; Lincoln likewise ignored the chain of command in issuing it.3

The record shows that the brief meeting ended with Lincoln approving two of Kilpatrick’s proposed objectives: freeing the prisoners on Belle Isle and at Libby, and severing Confederate communications. Lincoln further proposed that Kilpatrick distribute the president’s recent amnesty proclamation aimed at persuading secessionists to return to the Union fold. They also probably discussed how near Kilpatrick and his troopers came to Richmond during the Chancellorsville campaign raid. That experience was, evidently, Kilpatrick’s ticket of admission to the White House.

Perhaps, too, Lincoln repeated for the cavalryman a remark he had made at the time of Chancellorsville, to the effect that the Confederate capital was so lightly defended that Kilpatrick’s Federal cavalry ‘could have safely gone in and burnt every thing & brought us Jeff Davis.’4 Certainly the thought of Davis’ capture was fresh in the president’s mind–after all, he approved it as a stated objective of Butler’s recently aborted Richmond raid. (It may be noted here that by the generally accepted rules of civilized warfare of the 1860s, the capture of the opposing head of state and his chief advisers was a legitimate wartime objective and no doubt was discussed as openly in Richmond as it was in Washington. Assassination of civilian leaders, on the other hand, was regarded as beyond the pale.) Whatever their discussion may have included, when Lincoln sent Kilpatrick on to Secretary of War Stanton to work out the detailed planning for the raid, Jefferson Davis was not listed in any respect as a stated objective.

As will be seen, there is good reason to believe that Kilpatrick’s planning meeting in Stanton’s office at the War Department was pivotal in regard to the case of the Dahlgren papers. For now, suffice it to say that the sole surviving account of the meeting is Kilpatrick’s, dated February 16, and consists of his plan for the raid as submitted, at Stanton’s request, to the army’s cavalry command.

There were only three stated objectives for the raid: free the prisoners in Richmond’s military prisons, destroy Rebel communications, and distribute the president’s amnesty proclamation behind Confederate lines.5

Next, plans for the Richmond raid needed to be incorporated into the Army of the Potomac’s operations system. General Meade had reservations about the scheme but, learning that it was already approved by Lincoln and Stanton, dutifully went about putting it into practice. (Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, head of the Cavalry Corps, went on record as opposed to the plan.) Meade’s directive to Kilpatrick for the operation included the extraordinary disclaimer that ‘no detailed instructions are given you, since the plan of your operations has been proposed by yourself, with the sanction of the President and the Secretary of War….’ Meade, in short, would issue all the necessary enabling orders, but he did not know, and did not try to find out, anything more about Kilpatrick’s plan than Kilpatrick was willing to reveal. It would be an Army of the Potomac plan in name only. ‘The undertaking is a desperate one,’ Meade confided to his wife, ‘but the anxiety and distress of the public and of the authorities at Washington is so great that it seems to demand running great risks for the chances of success.’6

By now the undertaking had its second major player, Colonel Ulric Dahlgren. He appeared unannounced at Kilpatrick’s headquarters one day, said he had heard there was going to be a big cavalry raid, and told the general that he wanted to be in on it. That his offer was accepted and he was given the most responsible job in the operation after Kilpatrick’s is as curious as anything else in the whole tangled undertaking.

Dahlgren was twenty-one, tall, fair-haired, and dashing, with an abiding taste for adventure untempered by even a modicum of common sense. Dahlgren’s father, Rear Adm. John A. Dahlgren, was an expert in naval ordnance, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, and a close friend of the president’s. Lincoln, in fact, had gotten young Ulric a commission when he decided to give up his college studies and go to war in 1862. Since then he had served in a series of staff positions for army commanders Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and Meade, dashing recklessly into action whenever the opportunity offered itself.

He suffered a wound in his right leg in a cavalry skirmish following the Battle of Gettysburg and lost the limb below the knee to amputation. The still-recuperating Dahlgren, now fitted with a wooden leg and using a crutch, possessed no command experience when he appeared at Kilpatrick’s headquarters in the third week of February 1864 to ask for a job. Yet, the job he received was nothing less than command of the select contingent slated to break into Richmond and liberate the prisoners–and, as it proved, to carry out certain highly secret tasks as well.

Young Dahlgren was known to have friends in high places, including the White House, and that no doubt influenced Kilpatrick’s decision. But Kill-Cavalry also probably liked the fact that Dahlgren was, militarily speaking, an outsider. Kilpatrick would be operating with a secret agenda for his Richmond raid, and he required a like-minded subordinate to help him execute it. All of the Cavalry Corps’ colonels who were eligible for command roles in the expedition were either Regulars or, if volunteers, were veteran leaders familiar with what passed for the rules of civilized warfare. Kilpatrick was going to break those rules, and he read in Ulric Dahlgren someone who would have no qualms about also breaking them. On the eve of the raid, and fully briefed on the secret role he was to play, Dahlgren wrote his father a letter that reflected not qualms but only exuberance: ‘there is a grand raid to be made, and I am to have a very important command. If successful, it will be the grandest thing on record; and if it fails, many of us will ‘go up‘…but it is an undertaking that if I were not in, I should be ashamed to show my face again.’7

Another important participant in the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid–important, too, in later confirming the authenticity of the Dahlgren papers–was the Bureau of Military Information. This highly capable military intelligence unit had been founded by Colonel George H. Sharpe a year earlier, and by 1864 its expert staff was working in close harness with the Army of the Potomac. A BMI spy in Richmond furnished Kilpatrick with data on the city’s defenses. Captain John C. Babcock, the BMI’s liaison officer at Meade’s headquarters, pinpointed Confederate positions and strengths and supplied Dahlgren with a guide for his part of the mission. Captain John McEntee, Sharpe’s second in command, led a BMI party that rode with the Dahlgren raiders. It appears that McEntee was the only officer whom Dahlgren treated as a confidant, for he told him of his secret orders.8

After all the high-level planning and preparation, the execution of the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid came as a decided anticlimax. Early on February 28, under cover of an infantry and cavalry diversion that Meade launched westward around Lee’s left flank, Kilpatrick and Dahlgren led some thirty-six hundred troopers across the Rapidan River and past Lee’s right to begin their ride south toward Richmond.

The next day Dahlgren left the main column and started his contingent of 460 men on a wide swing to the west, aiming to strike the James River some twenty-five miles above Richmond. The plan called for him to cross the James at this point and proceed along its south bank and then push through the capital’s largely undefended southern portals. It was believed he could easily break into the city there and free the prisoners in Libby Prison and on Belle Isle.

Kilpatrick, meanwhile, would strike at the northern environs of the city. Depending upon circumstances, he would either break in to join Dahlgren or divert the defenders so Dahlgren might carry out his mission unopposed. According to the directive for the mission, the raiders would then leave the city with their liberated prisoners, turn eastward, and hasten down the Peninsula to gain a haven behind Ben Butler’s Army of the James.

Nothing went according to plan. Dahlgren discovered the James was running too high from the winter rains to cross. In a fit of particular savagery he turned on his guide, a black freedman supplied and vouched for by the BMI’s John Babcock, and had the man hanged from a tree on the riverbank. Proceeding toward Richmond but on the northern side of the James, Dahlgren soon ran into the city’s militia defenders. With that he gave up on his mission and turned away to the north in an effort to rejoin Kilpatrick.

Read More in Civil War Times MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in Civil War Times MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

That general, in the meantime, had reached Richmond’s outer defenses, where he found no sound or trace of Dahlgren’s force. Kilpatrick too lost all heart in the venture. After some desultory skirmishing, he withdrew to consider his next move and was assaulted from the rear by Rebel cavalry. Then, Kilpatrick reported, he ‘abandoned all further ideas of releasing our prisoners.’ Leaving Dahlgren and his men to their fate, Kill-Cavalry rushed down the Peninsula to Butler’s lines.9

A considerable number of Dahlgren’s party eventually reached the safety of the Peninsula, but Colonel Dahlgren and some one hundred of his men became separated and wandered off to the north and east of Richmond. On the night of March 2 they stumbled into an ambush set by Rebel cavalrymen and home guards. Lieutenant James Pollard, Ninth Virginia Cavalry, reported what happened next: ‘Col. Dahlgren who was in command and riding at the head of the column, saw a man who at that moment moved his position, and ordered him to surrender: which drew a volley from our men and Col. Dahlgren fell dead, struck by several bullets.’10

The story of the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid ought to have ended on that dismal note–a cavalry raiding force miserably managed by its co-leaders that came nowhere near achieving its purpose of rescuing the prisoners, cost substantially more in men and horses than any damage it inflicted on Confederate communications, and finally, saw one of its co-leaders shot dead and most of his men taken captive. Unfortunately, as matters turned out, that was not the end of the story.

Shortly after the ambush in which Dahlgren was killed, thirteen-year-old William Littlepage, a youthful member of a schoolboy company of home guards, came upon the colonel’s body and searched it for valuables. What he found came to be called the Dahlgren papers–two folded documents and a pocket notebook containing several loose papers inserted between the leaves. Young Littlepage turned his find over to his teacher and company commander, Captain Edward W. Halbach. At daylight the next morning, March 3, Halbach examined the papers and was shocked and appalled by what he found.11

The first of the documents, written in ink on Union army stationery bearing the printed heading ‘Headquarters Third Division, Cavalry Corps,’ was obviously an address to the officers and men of Colonel Dahlgren’s command. It covered two sheets, with the final six lines and the signature written on the back of the first sheet. It was signed, as best Halbach could make it out, ‘U. Dahlgren, Col. Comd.’ Among the inspiriting descriptions of their forthcoming mission was one riveting sentence: ‘We hope to release the prisoners from Belle Island first & having seen them fairly started we will cross the James River into Richmond, destroying the bridges after us & exhorting the released prisoners to destroy & burn the hateful City & do not allow the Rebel Leader Davis and his traitorous crew to escape.’

That savage injunction became even more explicit as Captain Halbach read on. The second document, unsigned but written in the same hand on both sides of a sheet of Cavalry Corps stationery, appeared to be a listing of instructions for a party of the raiders that was to operate in parallel with Dahlgren’s contingent. Among the instructions was this admonishment: ‘The men must keep together & well in hand & once in the City it must be destroyed & Jeff. Davis and Cabinet killed.’

The pocket notebook, which bore Dahlgren’s signature and rank on the opening page, contained a draft of his address to the troops, with corrected passages and other marks of composition but including the same murderous instructions as the finished copy. There was also a set of notations referring to planning for the raid and for carrying it out, including the stark direction: ‘Jeff Davis and Cabinet must be killed on the spot.’ The loose papers in the notebook contained less deadly instructions and itineraries relating to Dahlgren’s mission, plus an order of battle for the Confederate cavalry compiled by the Bureau of Military Information.12

Captain Halbach discussed the implications of the papers with fellow members of his unit, but, so far as the record shows, the only other person to read them that morning was his immediate superior, Captain Richard Hugh Bagby. Bagby, a minister, later made a verbal affidavit as to their contents.13 At 2 o’clock that afternoon, Lieutenant Pollard joined Halbach’s party and saw the Dahlgren papers. It was quickly agreed that the papers should be taken to Richmond, and Halbach turned them over to Pollard on the promise of faster delivery than the semi-weekly mail the captain relied on. By evening Lieutenant Pollard had the papers in the hands of his superior, Ninth Virginia Colonel Richard L.T. Beale, along with his report of the ambush of Dahlgren’s party and, by way of confirming identification, Dahlgren’s wooden leg. After reading the papers, Beale ordered Pollard to take them straight to Richmond the first thing the next morning. By his own decision, however, Beale held on to the pocket notebook. Apparently he thought it would furnish clues to additional raiders not yet captured. By not sending the notebook along with the other papers he delayed the process of confirming their authenticity.14

It was close to noon on March 4 when Lieutenant Pollard reached Richmond and delivered Dahlgren’s papers and his wooden leg to cavalry Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of the Army of Northern Virginia’s commander. Having led the ambush of the Dahlgren party, Pollard gave General Lee a full briefing on the finding of the papers and their identification. ‘Upon ascertaining their contents,’ Lee recalled, ‘I immediately took them to Mr. Davis.’ In the president’s office he found Davis in consultation with Secretary of State Judah Benjamin. Davis listened to Lee’s briefing and then read aloud from the two documents, the address, and the set of instructions. He made no comment until he reached the instruction ‘once in the City it must be destroyed & Jeff. Davis and Cabinet killed.’ At that, he remarked with a laugh, ‘That means you, Mr. Benjamin.’ Apparently dismissing the matter from his mind, the president told Lee to deliver the papers to the War Department and General Samuel Cooper, the Confederacy’s adjutant general, for filing.

By now it was well into the afternoon, and as the Dahlgren papers were passed around and their import discussed at the War Department, anger and indignation began to grow. Davis may have taken the threat of assassination lightly, but the officials of his government were of a very different mind. The message they read in these papers was war without quarter–war fought under the black flag. Had Dahlgren managed to carry out his plan, it was agreed, the consequences for Richmond would have been arson, pillage, the heads of government put to death, and the unlicensed brutality of vengeful prisoners of war visited upon the citizenry. The decision was made, apparently by Secretary of War James A. Seddon, to call in the newspapers and go public with this stark evidence of Northern barbarism.

First, of course, it was necessary to go back to President Davis and persuade him to approve the plan to expose the details of the papers. Then, the editors of Richmond’s newspapers had to be sent for and copies of the documents made for them. When the newsmen finally arrived at the War Department, a briefing was required to acquaint them with the circumstances of Colonel Dahlgren’s death and the discovery of the papers. It was well into evening now, and the editors hurried back to their papers with their stories and copies of the Dahlgren documents in time to meet the deadline for publication in the morning editions of March 5.15

Richmond’s editorial writers availed themselves of the opportunity to dip their pens in vitriol. The Richmond Dispatch headed its story, ‘The Last Raid of the Infernals: Their Plans Unveiled,’ and went on to describe the ‘diabolical plans’ of the raiders in detail. Nothing, said the Dispatch writer, could have tempted ‘any of the band of robbers and thieves to forgo the booty and butchery, the robbing and marauding that would inevitably fall to the lot of the braves who swept through the city of Richmond.’ The Richmond Whig asked if these men were warriors: ‘Or are they assassins, barbarians, thugs who have forfeited (and expect to lose) their lives? Are they not barbarians redolent with more hellish purposes than were the Goth, the Hun or the Saracen?’ The Richmond Inquirer offered a prediction: ‘Decidedly, we think that these Dahlgren papers will destroy, during the rest of the war, all rosewater chivalry, and that Confederate armies will make war afar and upon the rules selected by the enemy.’16

The newspapers shouted for the summary execution of the captured raiders, a remedy that found immediate backing within the War Department. Cooler heads called for Robert E. Lee’s opinion in the matter. Although condemning the ‘barbarous and inhuman plot,’ Lee said he could not recommend executing prisoners. He pointed out that the Dahlgren papers represented only intentions, not actions. None of the ‘atrocious acts’ had actually been carried out, nor was it clear that Dahlgren’s men were even aware of their leader’s intentions. In any case, said Lee, the execution of prisoners of war was a bad precedent to set and would only lead the enemy to retaliate. General Lee’s prestige was such that his opinion ended further discussion of executions.17

Other officers and bureaucrats in Richmond, however, refused to let the Dahlgren matter end. The notorious papers were photographed, and Secretary of State Benjamin sent copies to John Slidell, the Confederacy’s European envoy. Slidell was enjoined to show the Dahlgren papers and their message to the European powers in the hope of generating support for intervention. The papers, said Benjamin, offered ‘the most conclusive evidence of the nature of the war now waged against us….’ To enhance the effect of this message, Slidell engaged a London printer to reproduce Dahlgren’s address to his men and his instructions for the raid in the form of lithographed broadsheets. He had these tracts circulated widely in Britain and on the Continent.18

On March 30, General Lee was instructed to send a set of photographs of the papers by flag of truce to the high command of the Army of the Potomac and ascertain if Dahlgren was acting under the orders of his government and superiors and ‘whether the Government of the United States sanctions the sentiments and purposes therein set forth.’ On April 1, the Richmond Examiner published the contents of Dahlgren’s pocket notebook, belatedly retrieved from Colonel Beale, and the Dahlgren story once again became front-page news. The notebook, claimed the paper, confirmed the authorship of the earlier documents and their brutal message.19

All of this caused great discomfort for General Meade. He had not thought much of the raid’s prospects from the beginning, and its results were as bad as he had feared they might be. Then, when he saw copies of the Richmond papers for March 5, he was appalled. George Meade was an upstanding soldier and an honorable man, and he told his wife that these Dahlgren papers seemed to him ‘a pretty ugly piece of business.’ Kilpatrick was ordered to make ‘careful inquiries’ among those of Dahlgren’s men who had escaped capture and ask if the colonel had made or issued’such an address to his command as that which has been published in the journals of the day.’

Backed into a corner, Kilpatrick squirmed. His examination of Dahlgren’s men, he replied, turned up no one to testify to any address made by the colonel or to any instructions ‘of the character alleged in the rebel journals….’ The fact of the matter was, he elaborated, just an hour before they set out on the raid Colonel Dahlgren showed him the address he intended to deliver to his men. He, Kilpatrick, endorsed it ‘approved’ in red ink. It read just as printed in the Richmond papers–except for his endorsement and that fateful sentence about exhorting the prisoners to burn the hateful city and kill Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. ‘All this is false,’ Kilpatrick declared indignantly. Dahlgren must have chosen not to deliver the address but had retained it, Kilpatrick argued, and after the Rebels searched his remains they doctored the papers they found for their own invidious purposes.20

Skepticism about the Dahlgren papers’ authenticity surfaced in the Northern press soon after their publication in Richmond’s newspapers on March 5. The Philadelphia Inquirer saw in them ‘evidence of rebel manufacture.’ The New York Times headed a March 15 story, ‘The Rebel Calumny on Col. Dahlgren.’ What Kilpatrick now added to the witches’ brew was his admission that the Dahlgren papers were real enough–he affirmed seeing and endorsing the address–though he continued to assert that the version released by the Rebels had been doctored.

Meade’s reply to Lee stated that ‘neither the United States Government, myself, nor General Kilpatrick authorized, sanctioned, or approved the burning of the city of Richmond and the killing of Mr. Davis and cabinet…,’ and enclosed a somewhat toned-down version of Kilpatrick’s denial that only hinted that the papers had been tampered with. In short, no one had ordered or authorized Colonel Dahlgren to commit any criminal acts. The awful tale began and ended with him.21

There, officially, the matter rested. Yet as he prepared for the spring campaign, General Meade was not satisfied that the truth had prevailed and was unhappy, he told his wife, that he ‘necessarily threw odium on Dahlgren.’ He went on to tell her that he had sent General Lee the letter of Kilpatrick’s impugning the authenticity of the Dahlgren papers, and he added, ‘but I regret to say Kilpatrick’s reputation, and collateral evidence in my possession, rather go against this theory.’22

While Meade did not further describe this ‘collateral evidence,’ it was almost certainly the testimony of the Bureau of Military Information’s second-in-command, Captain John McEntee, who accompanied Dahlgren on the raid. In his diary for March 12, army Provost Marshal Brig. Gen. Marsena Patrick, under whose department the BMI operated, recorded a conversation with Captain McEntee. ‘He has the same opinion of Killpatrick [sic] that I have and says he managed just as all cowards do,’ Patrick wrote. ‘He further says, that he thinks the papers are correct that were found upon Dahlgren, as they correspond with what D. told him….’

General Meade could have gotten this same opinion from McEntee or by report from John Babcock, the BMI liaison officer at Meade’s headquarters who helped to plan the raid. Babcock left confirming testimony of his own in the matter. About this time he wrote: ‘Letters found on Dahlgren’s body published in Richmond papers….[are an] Authentic report of contents.’ Whether the collateral evidence came from McEntee or Babcock, both of whom qualify as expert witnesses, General Meade was convinced others were involved in the scheme to kill Davis. Yet it was not evidence that he wanted made public. ‘I was determined my skirts should be clear,’ he told his wife.23

The most vehement assertion that the Dahlgren papers were ‘a bare-faced, atrocious forgery’ concocted by ‘the miserable caitiffs’ in Richmond came, not surprisingly, from Dahlgren’s father, Admiral John Dahlgren. The grieving parent was deeply wounded by Richmond’s characterization of his child as ‘Ulric the Hun.’ During the summer of 1864 he was shown one of the lithographed broadsides of his son’s papers that John Slidell had been circulating in Europe. ‘I felt from the first…that my son never wrote that paper,’ the admiral said, pointing triumphantly to the signature on the address document: It was misspelled! And indeed on the broadsheet the name is clearly misspelled–U. Dalhgren rather than U. Dahlgren, with the ‘h’ and the ‘l’ transposed. The admiral also insisted that his son always signed his full first name, never just the initial. ‘I pronounce those papers a base forgery,’ cried the admiral.24

It would take the combined efforts of former Confederate general Jubal Early and historian James O. Hall to solve this particular puzzle. In 1879, Early carefully examined a set of the photographs taken in Richmond of the original Dahlgren address to his men. There were three photographic prints: one each of the two pages on cavalry corps stationery, and a third showing the concluding six lines of the address and the signature. Early pointed out that the conclusion of the speech was written across the back of page one, and that the inked writing had seeped through the thin paper. In the signature this show-through of letters from page one was quite marked, and it was possible to read Dahlgren’s signature, Early thought, as a misspelling of his name.

A century later, while examining one of the lithographed broadsheets of the address, Hall completed the solution to the puzzle. The London lithographer who worked with the papers in 1864 transferred the closing lines of the address and the signature to the bottom of page two in order to better fit the photographed document he was working from onto one piece of paper. Then, to produce an overall legible look to the finished broadsheet, he retouched the show-through area. When he cleaned up the signature–never having seen the name Dahlgren before–he made it what it looked like to him: Dalhgren.

It is unlikely that anyone looking only at the photographic set in 1864 and knowing Colonel Dahlgren’s identity would have made this mistake–and that includes Admiral Dahlgren. The name is hard to read in the photographic copy, to be sure, but to the initiated no misspelling is noticeable. But the admiral saw only the lithographic copy, where the misspelling is obvious. As for his insistence that Ulric always signed his full first name, that may have been true enough with his general correspondence, but in the case of formal official documents such as addresses to the troops, officers commonly used their initials. This was the only such address that Colonel Dahlgren ever composed, and he chose the customary form for his signature.25

Admiral Dahlgren went to his grave believing he had rescued his son’s memory from infamy and no doubt was comforted by that conviction. In fact, however, every claim of forgery ever applied to the Dahlgren papers, then and since, quickly unravels upon investigation. This is no less true of the case for forgery recently set forth in The Dahlgren Affair.

Read More in America’s Civil War MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in America’s Civil War MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

The notion that the Confederates forged the Dahlgren papers from scratch–that in fact no papers at all were found on Dahlgren’s body–is contradicted by no less an authority than Judson Kilpatrick, who admitted that he had seen such an address by Dahlgren on the eve of the raid. Kilpatrick simply denied that what he read and approved included the offending passage. In any case, the address, instructions, and pocket notebook contained scores of details of the raid and of its planning that the Confederates had no way of knowing. Thus any forgery plot had to have been limited to alterations of the existing documents.

The inflammatory sentence in the address calling for arson and murder falls toward the end of the first page of the document. If this was a forged interpolation, it would have required copying the entire two-and-a-half-page document–but only after obtaining new stationery created in imitation of the Federal Cavalry Corps letterhead. The same procedure needed to be followed for the sheet of instructions–entire recopying to include the murderous passage, on newly printed stationery. After that the documents had to be folded, creased, and soiled to the condition evident in the photographs.

The pocket notebook would require similar alteration. There is no photographic or other record of the notebook’s contents beyond what appeared in the Richmond Examiner of April 1, 1864, and beyond the testimony of those who saw and described it, so it is not known how difficult that forgery process might have been. Certainly it was more complicated than simply making a few additions to Dahlgren’s writings.

It is readily apparent that any program of forgery would require additional changes to the documents after they reached Richmond. The various lieutenants, captains, and colonels who saw the papers in the field had neither motive nor opportunity to carry out so sophisticated a ruse. Above everything else, they lacked access to a print shop to run off the necessary Federal army stationery. Therefore the entire forgery operation needed to have occurred in Richmond on March 4. More exactly, between noon on March 4, when Lieutenant Pollard handed the Dahlgren papers to General Fitzhugh Lee, and early evening, when copies were turned over to the Richmond editors in time for them to meet their printing deadline for the next day’s morning editions. These factors cause any and all of the forgery theories to collapse irretrievably. There was simply no time to carry out a forgery plot.

The accounting of events in Richmond on March 4, as already narrated, covers virtually every minute of that busy afternoon and evening–the papers being passed from Pollard to Fitzhugh Lee, from Lee to President Davis, from Davis to the War Department, from the department back to Davis and then back to the department, and finally the gathering of editors to receive their copies of the Dahlgren papers for publication. Each step in the sequence produced discussion and required a detailed briefing on the papers and the circumstances of their capture. Credible witnesses document each step. It is inconceivable that in those few hours, amid hectic circumstances, a secret plot to exploit the papers could have been hatched, the many necessary decisions made, special stationery printed, expert copyists located, the forged papers properly aged, and, finally, a cover story concocted and promulgated. (A similar forgery at breakneck speed would have been required for the pocket notebook, which reached Richmond on March 31 and was in print the next day.) Thus, the charge of forgery must be dismissed out of hand on this single count: It was literally impossible for the Confederates to have carried it off for lack of time.26

Last and certainly not least, a string of witnesses to the Dahlgren papers existed who would have had to have been corrupted into buying the new story of arson and pillage and murder–starting with Fitzhugh Lee, the commanding general’s nephew, and extending down the chain of command to Colonel Beale, Lieutenant Pollard, the Reverend Bagby, and teacher Edward Halbach. Each of these men went on record swearing that the papers taken from Colonel Dahlgren’s body that they read were the same papers printed in Richmond’s newspapers on March 5. That is hardly a cast of conspirators likely to universally bear false witness. In addition, such a deception would not have worked unless numbers of people who served in the Confederacy’s executive office and the War Department agreed to swear to eternal silence, an implausibility to say the least.

In order to finally close the case, however, it is necessary to dispose of certain peripheral evidences of alleged forgery, as set forth by Duane Schultz in The Dahlgren Affair. This is quickly done.

Unaware of the BMI’s role in the raid, Schultz labels as secondhand the testimony of John McEntee and John Babcock.27 Theirs was, in fact, firsthand testimony by eyewitnesses of solid reputation who had close connections with Dahlgren before and during the operation. In the case of McEntee, no one in the raiding party was in a better position to know Dahlgren’s secret agenda.

Shultz writes that it was significant that Dahlgren’s second in command and other subordinates testified that they were not told in advance of any secret agenda for the raid. An obvious inference, reading Kilpatrick’s admission that he saw Dahlgren’s address before the raid, is that Kill-Cavalry’s stricture stopped Dahlgren from delivering the address to his men. It is equally obvious that thereafter Dahlgren operated on a need-to-know basis. Until Richmond was entered and the prisoners released, nothing needed to be said about arson and murder, if for no other reason than the destructive impact the orders would surely have had on morale. It is safe to say that these troopers, Regulars and volunteers alike, had not enlisted to be assassins.

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in American History MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

In any case, the released and maddened prisoners were to carry out the heinous acts, not the raiders. Thus Dahlgren’s failure to inform his officers of his plans in advance was not in the least an indication that those plans were forgeries. It was perfectly proper for him to inform John McEntee, however, for McEntee and his BMI intelligence team were there to serve as guides once Richmond was entered; Dahlgren was aware they knew where to find Jefferson Davis and his cabinet.28

At two points in his instructions Dahlgren wrote, ‘As General Custer may follow me, be careful not to give a false alarm.’ Schultz points out that Brig. Gen. George A. Custer’s orders for a diversionary cavalry operation did not mention cooperating with the Dahlgren raiders and that therefore this is evidence of a Confederate forgery. In fact, Custer was directed to meet with the raid’s leaders before he issued his final orders, and it is reasonable to suppose that he and Dahlgren discussed a possible cooperation for carrying out the orders to destroy Confederate communications on the upper James, and Dahlgren wrote of this conference in his planning notes. Custer, ordered to march toward Charlottesville, would have been only some thirty miles from the point where Dahlgren intended to cross the James. A manuscript of unknown origin, and therefore uncertain credibility, even has Dahlgren revealing his secret orders to Custer. However that may be, it at least indicates the two were together prior to the raid. As for the Confederates forging these Custer references, there is nothing on the record to indicate that by March 4, when any deceit had to be completed, they even knew Custer would lead the cavalry diversion. Finally, no possible purpose would be served by adding this entirely irrelevant Custer detail to their forgery plot.29

In another supposed proof of forgery, Schultz finds it strange that three Confederate officers involved in the Dahlgren party’s ambush–Captain Edward C. Fox (who led the late-arriving Fifth Virginia Cavalry), Lieutenant James Pollard, and Colonel Richard L.T. Beale–made little or no mention of the infamous papers in their reports. In Fox’s case there is nothing strange about this omission, for there is no mention in Captain Halbach’s account of ever showing the papers to Fox. Pollard’s reports focused on the ambush itself, in response to queries from headquarters for details of the action to ascertain proper credit. In any event, Pollard, in an unpublished account of the incident, offered a fulsome description of the contents of the papers. Colonel Beale told of receiving ‘a note-book and sundry papers’ taken from Dahlgren’s body, certainly all that he needed to say on that subject for his report. By then, March 9, everyone knew of the papers and their contents, and there was no need for colorful writing. Nothing here supports a case for forgery.30

Finally, there is the question of why Colonel Dahlgren, ‘an experienced military officer,’ saw fit to carry such incriminating evidence on his person during a mission behind enemy lines.31 That is indeed a good question, but it speaks more to the character of Colonel Dahlgren than to any argument for forgery of his papers. Dahlgren was in fact utterly inexperienced in a command position. His voluminous note-taking suggests anxiety about that role, and his failure to take the basic precaution of destroying any mission papers he was carrying, much less these explosive ones, is evidence of his inexperience and his poor command judgment. Ulric Dahlgren was reckless, immature, and careless of consequences, characteristics perhaps suited to executing a bloody agenda like his but certainly ill-suited to rescuing a mission gone bad.

It can be accepted then that the authenticity of the Dahlgren papers is established beyond a doubt. There is not the least scrap of credible evidence for their forgery. There is ample evidence, on the other hand, for their content being exactly what was printed in the Richmond newspapers. The label ‘contestable’ does not apply to the Dahlgren papers.

That does not end the story, however. It leaves one further question of crucial importance to be answered: Who authorized the secret agenda of arson, pillage, and murder as set forth in the papers? The answer cannot be documented as readily as the question of the papers’ authenticity. Still, a credible presumption of guilt can be offered.

On March 7, two days after the Dahlgren papers appeared in print, an editor of the Richmond Sentinel expressed an opinion on the question of guilt that was widely applauded across the South. ‘Dahlgren’s infamy did not begin or die with him…,’ the editor wrote, ‘he was but the willing instrument for executing an atrocity which his superiors had carefully approved and sanctioned. Truly there is no depth of dishonor and villainy to which Lincoln and his agents are not capable of descending.’32

It is indeed quite impossible to imagine Ulric Dahlgren dreaming up this murderous scheme on his own. At age twenty-one, a newly appointed colonel acting in his first command role, Dahlgren lacked everything from motive to inspiration to initiate a program of assassination and wholesale destruction in the enemy’s capital. A willing instrument he certainly was but nothing more than that. The notes and instructions in his papers, especially those in his notebook, refer to plans of other commands beside his own and include notations about what are clearly orders and directions given him by his superior–who was, of course, Judson Kilpatrick. Indeed, in admitting to General Meade that he had read and approved Dahlgren’s address to his men, Kilpatrick was implicating himself in the villainy.

General Meade obviously recognized this, for he made sure that Judson Kilpatrick never again served in the Army of the Potomac. Kill-Cavalry next surfaced under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s command. ‘I know that Kilpatrick is a hell of a damned fool,’ said Sherman as he prepared for his march from Atlanta to the sea, ‘but I want just that sort of a man to command my cavalry on this expedition.’33

If young Dahlgren did not conceive the crime, the perpetrator of his deadly orders can only have been Judson Kilpatrick, conceiver and commander of the expedition. Assigning Kilpatrick to investigate the Dahlgren papers after their story broke in the Richmond papers was akin to assigning the fox to investigate casualties in the hen house. He smugly reported seeing a harmless address written by Colonel Dahlgren before the raid, thereby immediately marking the investigation closed. No matter how the case turned out, no matter what the perfidious Rebels might claim (or forge) concerning the papers, no one would be implicated but the late, lamented colonel. Adding that he had marked the address approved in red ink was simply a red herring.

Everything we know about Judson Kilpatrick indicates he would have had no scruples about plotting and executing a scheme of murder and destruction as outlined in the Dahlgren papers. But everything we know about him further suggests that he would never have dared to carry out this plot without at least tacit approval from some higher authority. Kilpatrick was ignoble enough to execute the mission’s secret agenda, but he was hardly brave enough to return with the corpse of Jefferson Davis unless he knew he would find a welcome in Washington.

Therefore, from Kilpatrick’s doorstep the trail of responsibility appears to lead straight to the office of Secretary of War Stanton. From first to last, there had been no intervening stops anywhere in the chain of command. Army commander Meade, whatever his views afterward, originally knew nothing beyond the stated objectives of the raid. General Pleasonton, commander of the Cavalry Corps and Kilpatrick’s immediate superior, distanced himself from the mission from its inception.

The plan for the Richmond raid and its stated objectives emerged from Kilpatrick’s private meeting with Stanton at the War Department on February 12. The idea for the raid’s secret agenda almost surely also came from that meeting. Stanton was never one to demonstrate respect for the niceties of civilized warfare. He had been, for example, the behind-the-scenes author of the set of draconian measures inflicted on Southern civilians in 1862. He was also exceedingly devious. An image comes easily to mind: Secretary Stanton describing for his visitor the perfidies of Jefferson Davis, rather in the manner of King Henry II speaking of Thomas à Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, before an audience of his eager courtiers, saying, ‘Will no one rid me of this man!’ To Judson Kilpatrick, ambitious and ruthless, his duty would have seemed clear enough. To his new patron, the thought of liberating the suffering prisoners from Belle Isle and Libby Prison to wreak vengeance on their captors would have seemed a pleasing rationalization for the scheme.

To be sure, there is no certain evidence tying Edwin Stanton to the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren plot. Only the fact of their February 12 meeting can be documented. Yet no other reasonable explanation meets the case. It cannot be imagined that Kilpatrick had the courage to carry this out on his own without sanction, and only Stanton could have filled such an approving role. It certainly cannot be imagined that the president countenanced political assassination and black flag warfare against civilians. Lincoln approved the capture of Davis, perhaps as a hostage for the release of Union prisoners, but nothing we know about the man suggests he would have gone beyond that.

What is especially significant in regard to Edwin Stanton’s possible role in this affair is his determination to get rid of the evidence. In late November 1865 Stanton ordered Francis Lieber, the keeper of captured Confederate records, to furnish him with everything relating to the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid. On December 1 of that year Lieber complied, handing over to Stanton a packet of papers and correspondence from the Confederate archives that included material found on Dahlgren’s body, including his instructions, the address to his men, and his pocket notebook. These papers–the Dahlgren papers–have not been seen since. Historian James O. Hall, who tracked down the Lieber-Stanton transaction and who has searched widely for the missing papers, writes with considerable authority that the’suspicion lingers that Stanton consigned them to the fireplace in his office.’34

Consequently, the present-day historical record of the Dahlgren papers consists of a badly faded set of the photographs taken by the Confederates, held in the National Archives; copies of Dahlgren’s address and instructions made by the London lithographer in 1864; and the transcriptions of these papers and of the pocket notebook printed in the Richmond newspapers on March 5 and April 1, 1864. Whatever Stanton’s motives were in laying his hands on the papers, historical research confirms both their existence and authenticity.

One irony of the Dahlgren case is that its wartime impact never depended upon this matter of authenticity. The Confederates never had the slightest doubt on that score. The papers were in their hands, and they could document where they had been found. In the South their implications were seen with stark clarity. ‘If the Confederate capital has been in the closest danger of massacre and conflagration,’ wrote the Richmond Sentinel‘s editor, ‘if the President and Cabinet have run a serious risk of being hanged at their own door, do we not owe it chiefly to the milk-and-water spirit in which this war has hitherto been conducted?’35

Some historians claim the heinous proposals contained in the Dahlgren papers were the motivation for the equally heinous shooting of Lincoln in Ford’s Theatre. This theory is well documented in Come Retribution: The Confederate Secret Service and the Assassination of Lincoln, by William A. Tidwell with James O. Hall and David W. Gaddy. Whatever linkage may be suggested between the assassin John Wilkes Booth and the plan of the would-be assassin Ulric Dahlgren, there is no doubt that the ‘milk-and-water spirit’ of warfare the Sentinel‘s editor complained of underwent a dramatic change, so far as the Confederacy was concerned, following publication of the Dahlgren papers. To Richmond’s leaders, the message seemed obvious: The North had taken off the gloves, and now the South felt free–indeed obliged as a matter of self-defense–to do the same. Subsequently there was a greatly enhanced sense of motive and a rationalization for the growing commitment to covert activity.

Read More in Civil War Times MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Read More in Civil War Times MagazineSubscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

The ultimate irony in this sordid tale of villainy and retribution is that it was all so senseless and unnecessary. The Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid was a fiasco, its fate sealed from the beginning with the choice of co-leaders. Its bloody secret agenda need never have emerged, at least during the war, but for hot-blooded young Dahlgren’s failure to destroy the incriminating papers he was carrying. Judson Kilpatrick, Ulric Dahlgren, and their probable patron Edwin Stanton set out to engineer the death of the Confederacy’s president; the legacy spawned out of the utter failure of their effort may have included the death of their own president.

1 Duane Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998); Stephen W. Sears, ‘Raid on Richmond,’ MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 11, no. 1 (Autumn 1998), 88-96; Stephen W. Sears, Controversies & Commanders: Dispatches from the Army of the Potomac (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 225-51; James M. McPherson, ‘A Failed Richmond Raid and Its Consequences,’ Columbiad: A Quarterly Review of the War Between the States 2, no. 4 (Winter 1999), 130, 133.

2 The Butler raid is detailed in Joseph George, Jr., ‘ ‘Black Flag Warfare’: Lincoln and the Raids Against Richmond and Jefferson Davis,’ Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography 115, no. 3 (July 1991), 291-318.

3 Stephen Z. Starr, The Union Cavalry in the Civil War, vol. 2, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981), 57-8; S. Williams to A. Pleasonton, Feb. 11, 1864, United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereinafter referred to as OR), ser. I, vol. 33, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), 552.

4 Lincoln to Joseph Hooker, May 8, 1863, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55), vol. 6, 202-3

5 Judson Kilpatrick to E.B. Parsons, Feb. 16, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 172-3.

6 A.A. Humphreys to Kilpatrick, Feb. 27, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 174; George Meade, ed., The Life and Letters of General George Gordon Meade, vol. 2, (New York: Scribner’s, 1913), 167-8.

7 Feb. 26, 1864, John A. Dahlgren Papers, Library of Congress.

8 The BMI is definitively examined in Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996).

9 Kilpatrick report, March 16, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 185.

10 James Pollard statement, Western Reserve Historical Society. Narratives of the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid are found in Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, Sears, Controversies & Commanders, and Virgil Carrington Jones, Eight Hours Before Richmond (New York: Henry Holt, 1957).

11 Edward H. Halbach statement, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 13 (Richmond: Published by the Society, 1902), 546-51.

12 Contents of the two documents are from the photographic copies of the originals, entry 721, serial 60, RG 94, National Archives; contents of the notebook are from the Richmond Examiner, April 1, 1864; the loose sheets are described in R.L.T. Beale statement, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 3, 221.

13 J. William Jones, ‘The Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid Against Richmond,’ Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 13, 551.

14 Halbach and Beale statements, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 13, 549, vol. 3, 221.

15 Fitzhugh Lee statement, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 13, 553-4; Judah P. Benjamin to John Slidell, March 22, 1864, James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, vol. 2, (Nashville: United States Publishing Co., 1905), 639.

16 Richmond Dispatch, Richmond Whig, Richmond Inquirer, March 5, 1864.

17 Robert E. Lee to James A. Seddon, March 6, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 222-3.

18 Benjamin to Slidell, March 28, 1864, Richardson, ed., Messages and Papers of the Confederacy, vol. 2, 641; Jones, Eight Hours Before Richmond, 125-6; James O. Hall, ‘The Dahlgren Papers: Fact or Fabrication,’ Civil War Times Illustrated (Nov. 1983), 36-7.

19 Samuel Cooper to R.E. Lee, March 30, Fitzhugh Lee to Cooper, March 31, R.E. Lee to Meade, April 1, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 223-4, 178; Richmond Examiner, April 1, 1864.

20 Meade, Life and Letters, vol. 2, 190-1; Pleasonton to Kilpatrick, March 14, Kilpatrick to Pleasonton, March 16, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 175-6.

21 Philadelphia Inquirer, March 11, 1864, New York Times, March 15, 1864; Meade to R.E. Lee, April 17, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 180.

22 Meade, Life and Letters, vol. 2, 191.

23 Marsena R. Patrick, Inside Lincoln’s Army: The Diary of Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Provost Marshal General, Army of the Potomac, ed. David S. Sparks (New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1964), 347-8; Babcock statement, John C. Babcock Papers, Library of Congress.

24 New York Times, July 28, 1864; John A. Dahlgren, Memoir of Ulric Dahlgren (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1872), 233.

25 Jubal A. Early to J. William Jones, Feb. 14, 1879, Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 13, 559; Hall, ‘The Dahlgren Papers,’ 37-8; broadsheet: collection of James O. Hall. See also David F. Riggs, ‘The Dahlgren Papers Reconsidered,’ The Lincoln Herald (summer 1981), 658-67.

26 Fitzhugh Lee to Samuel Cooper, March 31, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 224.

27 Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, 247-8.

28 Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, 250-2.

29 Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, 252-3; Pleasonton to Kilpatrick, Feb. 26, 1864, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 183; ‘Memoranda of the War,’ Virginia Historical Society, cited in Ernest B. Furgurson, Ashes of Glory: Richmond at War (New York: Knopf, 1996), 255n.

30 Reports of Edward C. Fox, James Pollard, R.L.T. Beale, OR, ser. I, vol. 33, 206-10; Pollard statement, Western Reserve Historical Society.

31 Schultz, The Dahlgren Affair, 252.

32 Richmond Sentinel, March 7, 1864.

33 James Harrison Wilson, Under the Old Flag (New York: Appleton, 1912), vol. 1, 372.

34 Hall, ‘The Dahlgren Papers,’ 39.

35 Richmond Sentinel, March 6, 1864.