It was seven minutes before midnight on August 28, 1945, when a large unidentified object appeared on the radar screen of USS Segundo, a Balao-class submarine on patrol south of Japan. It had been 13 days since Japan’s surrender announcement, and Segundo’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander S.L. Johnson, was on the lookout for remnants of Japan’s naval fleet. Segundo was 18 days out from Midway, and except for an encounter with a Japanese fishing boat, the patrol had been uneventful.

Soon after Segundo changed course to intercept the blip, Commander Johnson and his men realized they were on the trail of a Japanese submarine. After tracking the sub for more than four hours, Johnson tired of the cat-and-mouse game and radioed for it to stop, receiving a positive acknowledgement in reply. But as Segundo closed in, Johnson and his crew were literally in for a big surprise.

The vessel 1,900 yards off their bow was not your average Japanese submarine; it was I-401, flagship of the I-400 class known as Sen-Toku, or special submarines. At the time I-400s were the biggest submarines ever built, and they would remain so for nearly 20 years after the war. The sub Commander Johnson intercepted simply dwarfed Segundo.

Johnson and his men were about to discover that they’d happened upon one of the war’s most unusual and innovative weapon systems. Not only was I-401 bristling with topside weaponry, the sub was also designed to carry, launch and retrieve three Aichi M6A1 Seiran floatplane attack bombers. In other words, I-401 wasn’t just a major offensive weapon in a submarine fleet used to playing defense—it was actually the world’s first purpose-built underwater aircraft carrier.

Japan’s I-400 subs were just over 400 feet long and displaced 6,560 tons when submerged. Segundo was nearly 25 percent shorter and displaced less than half that tonnage. Remarkably, I-400s could travel 37,500 nautical miles at 14 knots while surfaced, equivalent to going 1½ times around the world without refueling, while Segundo could travel less than 12,000 nautical miles at 10 knots surfaced. I-400s carried between 157 and 200 officers, crew and passengers, compared to Segundo’s complement of 81 men.

Originally conceived in 1942 to attack U.S. coastal cities, the I-400 subs and their Seirans were central to an audacious, top-secret plan to stop the Allies’ Pacific advance by disguising the floatplane bombers with U.S. Army Air Forces insignia and attacking the Panama Canal. It was a desperate, Hail Mary–type mission to slow the American advance in the closing days of World War II. However, when the giant subs were finished too late in the war to be effective in stemming the Allied tide, they were reassigned to attack U.S. carrier forces at Ulithi Atoll, the launch point for a devastating air campaign against Japan in preparation for Operation Olympic, the planned invasion of the island nation.

But Commander Johnson and his men did not know any of this at the time because the United States was unaware that Japan had underwater aircraft carriers and knew little about its powerful attack bombers. As a result, when Johnson got a good look at I-401, he marveled at the “latest thing in Jap subs.”

After I-401 and its sister sub, I-400, surrendered in August 1945, U.S. officials were similarly staggered by their size, long-range capability and ability to carry and launch floatplane bombers. The Allies had nothing comparable in their fleet. Had the I-400s been built just six months earlier and succeeded in their mission, they could have thrown a major wrench into the Allied advance, giving Japan valuable time to regroup and rearm.

The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, which has restored the last surviving Aichi M6A1, calls the I-400–class subs and their Seirans “an ingenious blend of aviation and marine technology.” In other words, it was a state-of-the-art sub with a similarly sophisticated plane designed to inflict serious damage.

The I-400s boasted a maximum speed of 18.75 knots surfaced, or 6.5 knots submerged. They could dive to a depth of 330 feet, shallower than most U.S. subs at the time, and had a draft of 23 feet—fairly deep but hardly surprising given the sub’s size.

Nevertheless, the I-400s were to submarines what the Yamato class was to battleships. They carried Type 95 torpedoes, a smaller version of the Type 93 Long Lance torpedoes, the most advanced used by any navy in the war. The oxygen-powered 95s traveled nearly three times farther than the American Mark 14s, carried more explosive punch, left virtually no wake and were the second fastest torpedoes built during the war (Type 93s were the fastest). They were launched from eight 21-inch forward torpedo tubes, four on each side (two upper and two lower). Unlike U.S. subs, I-400s had no aft torpedo tubes, which could prove a shortcoming in certain situations, but topside they were all business, with one 5.5-inch rear- facing deck gun, three triple-barrel 25mm anti-aircraft guns on top of the aircraft hangar and a single 25mm gun on the bridge.

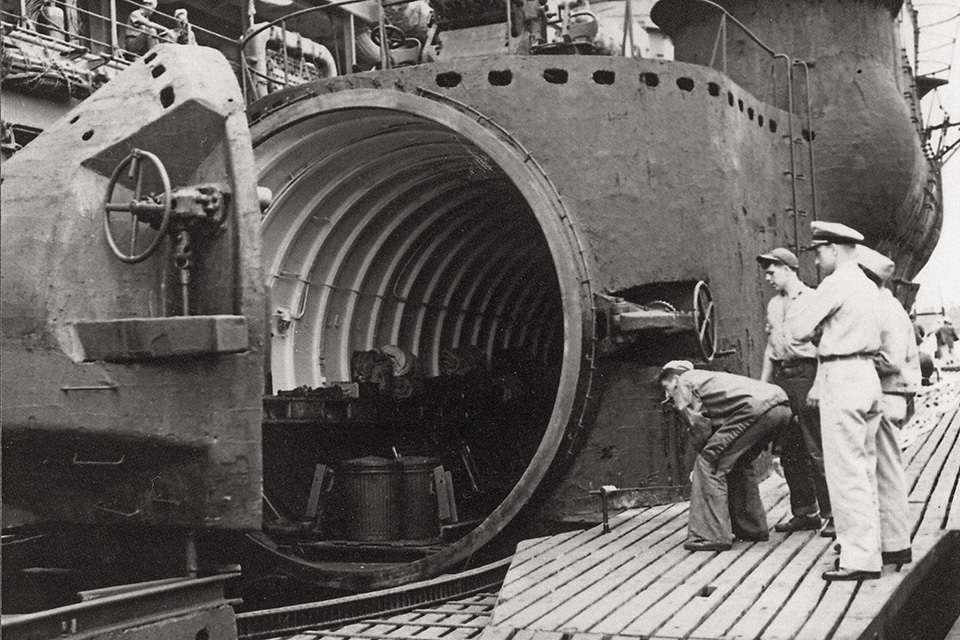

The most innovative aspect of the I-400 subs, however, was their role as underwater aircraft carriers. Each packed three Seirans in a huge, 115-foot-long watertight hangar that projected from the bridge structure onto the deck. The hangar was so large that the conning tower had to be offset seven feet to port of centerline to accommodate it. The hangar in turn was offset two feet to starboard to compensate for its size. A massive hydraulic hangar door opened onto a 120-foot-long compressed-air catapult that launched the Seirans. A collapsible hydraulic crane lifted the planes back on board for hangar storage. It was the unusual, bulbous shape of I-401’s hangar that especially captured the interest of Johnson and his men.

In a recent interview at his son’s home outside Tokyo, Lt. Cmdr. Nobukiyo Nambu, who captained I-401, said the I-400 subs were maneuverable for their size. “I-401’s maneuverability under the sea was no different than other subs, though it had a greater turning radius on the surface,” recalled the 97-year-old, who is surprisingly tall for a submarine captain and still maintains an erect bearing.

Born in 1911, Nambu is a living history lesson. Though he walks with a cane and is hard of hearing, he recently authored a successful book about his adventures aboard I-401. His navy career began with a scholarship to Etajima, Japan’s naval academy, attending submarine school and graduating as a member of class number 62. Nambu served as the chief torpedo officer on I-17 during the Pearl Harbor attack and later shelled Santa Barbara, Calif., in February 1942, an incident that became the basis for Steven Spielberg’s movie 1941. After the war he served in Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force, achieving the rank of rear admiral.

Lieutenant Muneo Bando, Nambu’s chief navigator and a sometime observer aboard a Seiran, remembered I-401 as harder to navigate than a smaller sub. He said the big boat required one kilometer to stop and the crew experienced a 30-second delay in response to steering commands. But I-400s gained a reputation for riding smoothly in rough seas due to their double hull construction—essentially two large steel tubes laid side by side.

The I-400s were specifically designed as underwater aircraft carriers to support the M6A1 Seiran, designed by Aichi’s chief engineer, Toshio Ozaki, and built in the company’s Nagoya factory. The Seiran was intended to strike directly at the U.S. mainland. Unlike previous sub-based aircraft designed for reconnaissance or defensive measures, it was a purely offensive weapon built to command respect.

In the book I-400: Japan’s Secret Aircraft-Carrying Strike Submarine, Lieutenant Tadashi Funada, a test pilot who flew the first Seiran prototype, is credited with naming the aircraft. The name Seiran is composed of two Japanese words that can be translated as “storm out of a clear sky.” According to the authors, Lieutenant Funada’s hope was that the bomber would gain the key element of surprise by suddenly seeming to appear out of nowhere.

Aichi completed the first Seiran prototype in the fall of 1943, and the Imperial Japanese Navy was happy enough with the result to order production to start immediately. The original production goal of 44 aircraft was eventually reduced to 28 (including two M6A1-K trainers) due to the plane’s cost and war-driven material shortages, not to mention two major earthquakes and relentless bombing by B-29s, both of which damaged Aichi’s Seiran factory.

Former Lieutenant Atsushi Asamura, the leader of Squadron Number 1, which was responsible for the planned attack on the Panama Canal, confirmed the difficulties surrounding Seiran production. Interviewed in his Tokyo apartment, the 86-year-old former pilot said, “The Seirans that were custom built were of good quality, but as they scaled back production the quality became poor due to material shortages and difficult manufacturing conditions.” In fact, many of the Aichi employees responsible for building the Seirans were high school students.

Nevertheless, Lieutenant Asamura, who remains fit and speaks in a strong voice, recalled the Seiran as “a good performance aircraft,” confirming its reputation as streamlined and responsive, with excellent attack power. “It was a versatile plane since it was both an attack bomber and had long distance range,” Asamura said, illustrating the Seiran’s easy handling by holding his arms out like wings, then grabbing an imaginary stick. “But there was no big difference in how it handled a sea landing compared to other planes.”

Asamura also recalled that the Seiran’s liquid-cooled engine provided pilots with much better visibility than the bulkier and more common air-cooled engines in use at the time. The Atsuta 30 series 12-cylinder inverted Vee engine (Japan’s version of a German Daimler-Benz DB 601A) delivered 1,400 hp, and its liquid-cooled design meant it didn’t need as much warm-up time as an air-cooled engine, so the plane could launch faster. Given the danger subs faced on the surface, this was a distinct advantage.

The Seiran featured a metal frame construction with a riveted metal fuselage and triple-blade propeller. It required a crew of two: a pilot and an observer who sat in a tandem configuration. The observer served as radio operator and navigator, also manning the flexible rear-facing 13mm machine gun, which flipped up from a recess in the fuselage and locked into place for firing. The aircraft carried either a 551-pound bomb with its floats attached or a 1,764-pound bomb (or torpedo) without floats. The heavier ordnance meant that the pilot would have to ditch the plane upon his return, or it was a one-way suicide mission.

By necessity, the Seiran had hydraulically folding wings similar to the Grumman F6F Hellcat’s that rotated 90 degrees to ensure the aircraft fit inside its small, tubelike hangar, which was only 11 feet 6 inches in diameter. Part of the horizontal stabilizer and the tip of the vertical stabilizer also folded down to accommodate the tight fit. The plane’s floats were detachable and stored separately, as were their support pylons and spare parts.

One of the key requirements of the Seiran was that it could be rolled out on a dolly, assembled by its ground crew and launched in a very short time. Reports vary on how fast this could be accomplished. According to Commander Nambu, intensive training enabled the I-401 crew to launch three planes within 45 minutes. But Nambu also noted that given the rough handling the Seirans received during sea launches and landings, it was difficult to keep all three in good operating condition at the same time.

The Smithsonian notes the Seirans had “interesting design features built in…that ranged in engineering quality from the ingenious to the seemingly absurd.” The fact that some of the floatplane’s parts were painted with luminescent paint for night assembly certainly has to fall into the former category. Lieutenant Asamura claimed the Seiran cost “50 times more than a Zero to produce,” and though it’s not possible to confirm the exact cost, clearly they were expensive to manufacture.

Although some German and British subs had carried reconnaissance aircraft on their decks during World War I, Japan was the only nation to use submarine-launched aircraft in WWII. At the beginning of the war, it had approximately 63 oceangoing subs, 11 carrying one catapult-launched reconnaissance plane each. Eventually, Japan would expand this to a total of 41 aircraft-carrying subs.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet and architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, gets credit for the I-400 class of submarines and its Seiran bomber, though I-401’s Commander Nambu says the actual idea for an underwater aircraft carrier probably originated from lower down in the command structure. Admiral Yamamoto’s vision in 1942 was for the underwater aircraft carriers to launch their Seiran attack bombers against U.S. coastal cities such as Washington, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, to deliver a Doolittle-like blow to American morale.

The original plan was to build 18 I-400– class subs, but after Yamamoto was ambushed and killed by Lockheed P-38 Lightnings in April 1943, the guiding hand behind the I-400 subs was gone. Construction plans were scaled back to nine subs, due in part to steel shortages. Actual construction began on five subs but was later reduced to three, of which only two (I-400 and I-401) made it into service. A third, I-402, was converted into a fuel tanker and completed in July 1945 but never saw active duty.

Final design plans for the underwater aircraft carriers were finished by May 1942, and construction on the first sub (I-400) began at Kure’s dockyards in January 1943. I-401’s construction quickly followed. By December 30, 1944, I-400 was complete, and I-401 was completed less than two weeks later. Both subs immediately deployed for their shakedown cruises.

In December 1944, the Imperial Japanese Navy organized the 1st Submarine Flotilla and 631st Kokutai (Air Corps), with Captain Tatsunoke Ariizumi commanding both units. The force consisted of I-400, I-401 and two AM-class subs, I-13 and I-14, which were smaller and carried two Seirans each, for a total of 10 Seiran bombers. An experienced naval officer from a distinguished military family, Ariizumi and had been in charge of the midget sub attacks at Pearl Harbor.

In March 1945, Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa, vice chief of the navy general staff, toyed with a plan to use the Seirans to unleash biological weapons on a U.S. West Coast city in revenge for the firebombing of Tokyo. The notorious Japanese Unit 731 had already conducted successful experiments in Manchuria using rats infected with bubonic plague and other diseases to kill Chinese citizens. But the operation was canceled later that month by General Yoshijiro Umezu, chief of the army general staff, who declared, “Germ warfare against the United States would escalate to war against all humanity.” Instead, the Japanese decided to target the Panama Canal.

By 1945 there was little doubt among the Japanese that the war was going badly. If Germany was defeated, the Allies would be on their doorstep next. The Panama Canal was a major transshipment point for war materiel essential to the Pacific theater. Closing it off would slow down if not stop the Allied advance, which would give Japan much-needed breathing room. As a result, the plan to attack the canal, drain Gatun Lake and block Allied shipping made strategic sense.

Japanese engineers had helped to build the canal, so Japan had construction plans to work from. Since Japanese carriers couldn’t get close enough to attack without being discovered, the 1st Submarine Flotilla and 631st Koku-tai were selected for the task.

The four submarines were to leave Japan in June 1945 and surface 100 miles off the coast of Ecuador, where they would launch their 10 Seirans at night. The Seirans, painted to resemble U.S. Army Air Forces planes, would fly northeast over Colombia, turn west over the Caribbean, then attack from the north at dawn, torpedoing the Gatun locks. After returning to their launch point, the pilots would ditch their planes and swim to their respective subs.

Before I-400 and I-401 crews could begin training for the mission, however, the Japanese had to deal with a severe fuel shortage resulting from the Allies’ sinking their tankers. The I-400s did not have enough diesel to complete their mission, so I-401, disguised as a frigate with a false funnel, was ordered to Manchuria to get more fuel. On April 12, shortly after departure, the sub was damaged by a mine and had to return to port for repairs, but I-400 was sent in its place and returned with the necessary fuel.

By June 4, the sister subs had arrived in Nanao Bay for battle training. There the crews practiced speeding up the assembly of the Seirans, night catapult launches, and submerging and surfacing the submarines in preparation for launches.

“The sub’s pitching and rolling made catapult launches difficult; the navigator had to time it just right,” Lieutenant Asamura remembered. “Nevertheless, compressed air made it a smoother launch than catapults that used gunpowder.” Asamura also recalled the importance of launching against the wind to make sure the Seiran got enough lift. As a result, he said, “It could be dangerous if the wind direction changed on you during a catapult launch.”

A full-scale mockup of the Gatun locks was constructed to practice Seiran torpedo runs, but training conditions proved extremely difficult. The I-400s had to deal with relentless Allied bombing and strafing as well as heavily mined waters. There were not enough experienced pilots for the mission, and two Seirans were lost during training. In fact, only one pilot had the requisite torpedo experience, so it was decided the Seirans would carry a single large bomb instead of a torpedo. To ensure success, the pilots would fly their aircraft directly into the locks rather than risk inaccurate bomb drops.

Born in Osaka in 1922, Asamura now lives in Tokyo’s Nezu section in a high-rise apartment with his wife. A small, balding man, he has an interest in history and a fair understanding of English.

Asamura remembered that for the pilots, “life on a submarine was 180 degrees different than flying in the air. You couldn’t tell night from day on the sub, so I never knew what meal I should be eating.” But he also noted that though they ate canned rather than fresh food, there was enough to go around, which often wasn’t the case for the Japanese army. Pilots had no duties to perform on the sub, and he recalled that crew relations were good.

Asamura said the Panama Canal mission was an open secret among I-401’s crew. But with the U.S. already positioning an enormous armada of ships, aircraft and troop transports in the Pacific for the planned invasion of Japan, the Japanese navy’s high command decided the Seirans should attack U.S. carriers at Ulithi Atoll instead of the canal.

Captain Ariizumi was disappointed that the Panama mission had been canceled and argued the decision with his superior officers. According to Captain Zenji Orita in his 1976 book I-Boat Captain, Ariizumi was told, “A man does not worry about a fire he sees on the horizon when other flames are licking at his kimono sleeve!”

Asamura recalled that he was not disappointed at the change in mission objective despite the intensive preparation because he knew the situation. “I understood the importance of the Panama mission, but the U.S. was on our doorstep and that was more imperative,” he said.

I-400 and I-401 received orders on June 25 for a two-part operation. The first phase was called Hikari (light). I-13 and I-14 were to offload four Nakajima C6N1 Saiun reconnaissance aircraft at Truk Island, where the planes would scout the American fleet at Ulithi and relay target information to I-400 and I-401. The second part of the operation, called Arashi (storm), involved the two I-400 subs launching their six Seirans to carry out kamikaze attacks on the U.S. carriers and troop transports in coordination with Kaiten (manned torpedoes).

Fake U.S. markings were applied to the Seirans on July 21, and two days later I-400 and I-401 set out following separate routes to reduce their chance of discovery. The mission, however, was plagued by problems. En route, a Japanese shore battery accidentally shelled I-401, and I-13, carrying two of the Nakajima surveillance planes, was sunk, most likely by an American destroyer. Additionally, I-400 failed to pick up a crucial radio message, which led to its missing its rendezvous with I-401. As a result, the attack was postponed until August 25, giving the two subs time to regroup.

I-401’s Commander Nambu recalled picking up Allied broadcasts on August 14 announcing that Japan would soon surrender, but he did not believe them at the time, assuming they were either propaganda or a trick. Even when Emperor Hirohito made his August 15 radio broadcast asking the Japanese people to “endure the unendurable,” the captain and lieutenant commander debated whether to continue the mission, return to Japan or scuttle the ship. Asamura said he missed the emperor’s surrender announcement because he was sleeping at the time, but was not surprised that Japan had to surrender as he knew the war was going badly.

Some of I-401’s crew wanted to go ahead with the plan to attack U.S. forces at Ulithi. In fact Nambu said that even after I-401 received specific instructions canceling the operation and ordering the sub back to Japan, some crew members wanted to keep the sub and become pirates instead.

Finally, I-401’s crew hoisted the black triangular surrender flag and on August 26 fired all of its torpedoes. The crew destroyed its codes, logs, charts, manuals and secret documents, and after punching holes in the Seirans’ floats, either pushed or catapulted them into the sea. I-400 surrendered on August 27 on its way back to Japan, and two days later I-401 encountered USS Segundo.

Captain Ariizumi appointed Lieutenant Bando, I-401’s chief navigator, to negotiate the surrender of his flagship to Segundo, in part because Bando spoke some English. Despite the Japanese navigator’s English training, however, Commander Johnson wrote in his war patrol report that he and Bando “held a doubtful conversation…in baby talk plus violent gestures.”

Johnson initially responded with disbelief to Bando’s assertion that I-401 carried 200 men, stating, “This could quite possibly be an error on his part, as I think the war interrupted English instruction.” But of course Bando’s figure was correct.

Bando remembered Captain Ariizumi becoming impatient with the surrender negotiations, preferring to scuttle the submarine and have the officers and crew commit suicide. Johnson was also concerned about the possibility of mass suicide aboard the sub, but after some haggling, terms were agreed upon and a prize crew from Segundo boarded I-401, checked that there were no torpedoes left, chained the hatches open to prevent the sub from diving and accompanied it on its return to Japan.

At 0500 hours on August 31, the U.S. flag was hoisted aboard I-401 and Commander Nambu delivered two samurai swords as a symbol of surrender to Lieutenant J.E. Balson, Segundo’s executive officer and prize crew chief. Shortly thereafter, Ariizumi shot himself in his cabin with a pistol; his body was subsequently buried at sea. “It was a small boat,” Asamura said. “Everyone knew the commander had killed himself.”

Nambu recalled that the officers and crew of I-401 “received gentle treatment by the U.S. Navy after the surrender.” Bando noted that Johnson even invited him to visit the United States after the war.

Escorted by Segundo, I-401 sailed to Yokosuka in Tokyo Bay, where it officially surrendered to the U.S. The sub was stricken from the Imperial Japanese Navy’s active duty roster on September 15.

The I-400 submarines only saw eight months of service from their launch to their surrender, and the Seirans likely never flew in combat. But the U.S. Navy was so impressed by the underwater aircraft carriers that it decided the subs merited further study. On December 11, 1945, I-400 and I-401 sailed with an American prize crew of four officers and 40 enlisted men (as well as a load of smuggled Japanese war souvenirs in I-400’s hangar) from Yokosuka to Pearl Harbor. They were escorted by a sub rescue vessel, and after an uneventful trip arrived in Pearl on January 6, 1946.

According to the late Thomas O. Paine, who served as executive officer and navigator during I-400’s trip to Pearl Harbor, the absence of manuals for the I-400s did not stop American crews from figuring out how to operate the subs because “Japanese submarine design…followed fairly standard practice.” In an unpublished memoir, Paine wrote that the prize crews developed their own drawings and color codes for I-400’s operating systems as well as “learned under the critical eyes of Japanese petty officers.”

Paine explained that I-400’s interior included a “large torpedo room, chief’s quarters, radio shack, capacious wardroom featuring fine wooden cabinet work, a Shinto shrine, officer’s staterooms, and a large control room.” He also described the sub’s aft crew compartment as having “raised wooden decks polished like a dance floor—you took your shoes off before walking there.”

Both subs were extensively studied at Pearl, though the Navy never tried submerging either one. When the Soviets asked for access to the I-400s as part of an information-sharing agreement, U.S. officials decided to prevent them from obtaining potentially disruptive technology by scuttling the submarines. I-402 was sunk off Japan’s Goto Island in April 1946, and I-401 was torpedoed by the submarine Cabezon and sunk off Pearl Harbor on May 31. I-400 quickly followed it to the bottom.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag

In March 2005, the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory, using two deep-diving submersibles, located I-401 off the coast of Kalaeloa in 2,665 feet of water. The main hull sits upright on the bottom. The bow is broken off just forward of the airplane hangar, and the “I-401” designation is still clearly visible on the conning tower. Otherwise the sub appears in remarkably good condition. I-400 and I-402 have yet to be found.

Nambu, who knows that his old sub command has been rediscovered on the ocean floor, believes I-401 and its Seirans comprised a strategic weapon. But though he feels the Panama Canal bombing mission was an objective worthy of his flagship sub, he thinks the mission would have needed to occur at least a year earlier than planned in order to be truly effective.

Some reports have suggested that the I-400 submarines’ technology was incorporated into future U.S. submarine innovations like the Regulus sub-launched missile program, much as Wernher von Braun’s V-2 program became the backbone of future U.S. ballistic missile and space programs. Though this may give the technology more credit than it warrants, the underwater aircraft carriers were clearly superior in important ways to subs at the time.

And though Nambu is proud of what he accomplished in defense of his country, he feels Japan did not make full strategic use of submarines during World War II. “Subs were not meant to be deployed as cargo carriers,” he said, referring to the many missions in which submarines were used to provide supplies to the Japanese army on remote island outposts. “Subs were meant to attack.”

Fortunately for the United States, I-401 and its Seirans never got the chance.

John Geoghegan, who frequently writes about marine and aviation adventure and exploration, is a director of the SILOE Research Institute in Marin County, Calif. Additional reporting for this article was done by Takuji Ozasayama. Further reading: I-400: Japan’s Secret Aircraft-Carrying Strike Submarine, by Henry Sakaida, Gary Nila and Koji Takaki.

Want to add the “Canal Buster” to your collection? Build your own Seiran here!

Japan’s Panama Canal Buster originally appeared in the May 2008 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!