Facts, information and articles about the James Younger Gang, famous outlaws from the Wild West

James Younger Gang summary: The James-Younger Gang was notorious in the latter part of the 1860’s. It was located in Missouri. Most of their unlawfulness centered on robberies. The gang consisted of the James brothers, Jesse James and his older brother Alexander Franklin “Frank” James. Sometimes the Younger brothers, Jim, John, Bob and Cole Younger would join the gang temporarily. Other members would be part of the gang at one time or another. These included John Jarrette who was Jesse James’ brother-in-law, Clel Miller, Arthur McCoy, Matthew Nelson, Charlie Pitts, and Bill Chadwell.

This notorious gang was the outgrowth of men who had known each other the bushwhackers of the Civil War. When the war was over, these were among the men who seemed not to fit into society any longer. They took to robbing banks to support themselves. While they were not very organized at first, some of them drifting together by chance, they soon became a gang that had grown and learned from their mistakes.

While the gang was in Northfield, Minnesota, a Swedish immigrant farmer was killed by a bullet as the gang was trying to rob the bank. The assistant cashier inside the bank would not open the vault for the gang and was shot for his refusal. All the gang got from their robbery attempt was a bag full of nickels. After this failure, they decided to go their separate ways to elude the police.

Eventually, a gun battle ensued between the James Gang and the police. One bullet killed Pitts and others caught the Younger brothers but not killing them. Eventually, the Younger brothers were sentenced to life in prison. Jesse James was killed by one of his own gang members.

![By Cole Younger. No photo credit. The Henneberry Company 1903 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Bob Younger](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/Bob_Younger.jpg/256px-Bob_Younger.jpg)

![By Cole Younger. No photo credit. The Henneberry Company 1903 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Jim Younger](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7a/Jim_Younger.jpg)

Articles Featuring James Younger Gang From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

The James-Younger Gang and their Circle of Friends

During their outlaw careers, the James brothers and the Younger brothers dealt in fine-blooded stock, raced thoroughbreds and rode beautiful American Saddlebreds. All were expert horsemen, always paying careful attention to their animals, which were essential tools of their ‘business.’ Also essential to the West’s most famous outlaw brothers’ success was the support of a circle of trusted friends. Included in those supporters were such prominent and influential families as the Hudspeths, who raised stock and bred horses on their vast landholdings in JacksonCounty, Missouri. Among the most outspoken was Virginia-born newspaper editor John Newman Edwards, who had been Confederate General Joseph O. Shelby’s adjutant during the Civil War. Edwards’ printed words provided alibis and excuses for the James-Younger Gang, which was seen by him and many other Southerners as a collection of well-liked former guerrillas forced into living outside the law by a repressive Republican Reconstruction federal government.

After the Civil War, other ex-guerrillas — who had ridden with the notorious William Quantrill and ‘Bloody Bill’ Anderson — were as well known as the Jameses and Youngers. Some were recruited as gang members. These men were not only known in Missouri but also in a wide area across the South from Kentucky to Texas. The gang’s base, where the leaders recruited and planned, was the farm of Frank and Jesse’s wealthy uncle, George W. Hite, at Adairville, in Kentucky’s Logan County, 10 miles from Russellville, scene of an 1868 bank robbery. The James boys’ father, Robert, was born in Logan County and graduated from Georgetown College near Midway, Woodford County. Their mother, Zerelada Cole James Samuels, was born at Midway. After meeting and marrying in Kentucky, they had moved to Missouri in the early 1840s.

From February 13, 1866, through the September 7, 1876, Northfield raid in Minnesota, the James-Younger Gang reportedly robbed 12 banks, five trains, five stagecoaches and the gate cash box of the ticket booth at the Kansas City Exposition. A network of friends showed sympathy and support for Frank and Jesse even after the famous fiasco at Northfield. Others, though, turned against the boys — not only those people who could no longer see them simply as ‘victims’ of Northern aggression and big business, but also personal acquaintances and even some new gang members.

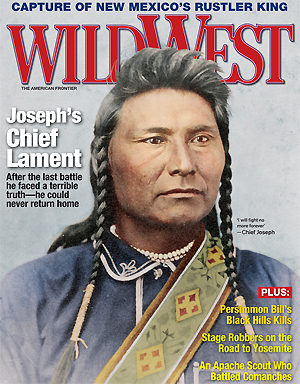

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

In such a dangerous line of work, the old gang could not last forever. Gang member Oll Shepard was killed in 1868 at Lee’s Summit. Brothers Bill (‘Bud’) and Tom McDaniel were captured and killed in 1874 and ’75, respectively. Tom Webb, alias Jack Keene, was captured in Kentucky with Tom McDaniel. Up in Minnesota, Clell Miller, Bill Chadwell (alias Bill Stiles) and Charlie Pitts (alias Sam Wells) were killed, while brothers Cole, Jim and Bob Younger were wounded, captured and imprisoned for a quarter of a century in the state penitentiary. Thus, in 1879, when Frank and Jesse James resumed their criminal careers in Tennessee and Kentucky, no old gang members were available. The loyal network of friends, however, provided them alibis and gave them sanctuary as Frank and Jesse lived freely using aliases — ‘Ben J. Woodson’ and sportsman ‘Tom Davis Howard.’

The James-Younger Gang always rode in style. Newspaper accounts of the gang’s robberies often reported that the outlaws were mounted on the finest horseflesh in Kentucky. The boys took great pride in their horses, too. According to the Little Rock Daily Gazette, when traveling on a raid, the gang usually rode ‘two abreast about one hundred yards apart. One man would lead a horse, and he being the odd man, would ride at the rear.’ This practice, which allowed one horse to rest while the others were ridden, was mentioned by eyewitnesses after the train robbery near Gads Hill, Mo., on January 31, 1874.

All along their routes, the outlaws conducted themselves as gentlemen, paying for everything they received and not drawing attention to themselves. As no photographs of them were yet published, they could take on any identity they wished. While traveling — to such places as Columbia, Ky., in April 1872; Adair, Iowa, in July 1873; Corinth, Miss., and Muncie, Kan., in 1874; and to the new bank at Huntington, W.Va., in September 1875 — they used maps and a compass and, to be on the safe side, avoided well-traveled roads. Daniel Webster ‘Kit’ Dalton, a former guerrilla and gang member and the author of Under the Black Flag, said that he supplied information for the Corinth bank robbery and also rode with the gang when it was operating in Missouri, Kentucky and Texas. The boys did get around and were always prepared for trouble, each member wearing as many as three revolvers and carrying rifles and shotguns in their saddle scabbards. After their crimes, they could always count on family and friends to provide hideouts and support.

The James and Younger boys considered themselves sporting men (Frank and Jesse’s cover in Nashville from 1877 to 1881; Jesse James was co-owner of the racehorse Jim Malone, which won $5,000 in 26 starts in 1880-81). Alexander Frank James, who was born on January 10, 1843, and Jesse Woodson James, who was born on September 27, 1847, learned to ride and appreciate horses in the 1850s — and those lessons paid off in the 1860s. During the war and their postwar criminal careers, good horses meant the difference between freedom and capture, life and death. Horses were also a lot of fun. Frank and Jesse were no strangers to the health resorts frequented by the wealthy sporting crowd of their day — such as Monegaw Springs in St. Clair County, Mo., and Hot Springs, Ark., where there was horse racing. The Daily Gazette and John Gould Fletcher’s book Arkansas reported that the outlaws had been seen at the springs before the January 15, 1874, stagecoach robbery on the road between Hot Springs and Malvern, Ark. By the early 1870s, Frank and Jesse were also going to Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and Long Branch, N.J., (Monmouth Park racetrack opened near there on July 30, 1870) to run their thoroughbreds. A picture of Jesse was taken at the Long Branch resort. Records in Kirk’s Guide to the Turf show Jesse James’ horse Skyrocket, which was foaled on April 12, 1873, near Midway, Ky., raced at Monmouth Park in 1875-76.

In the meantime, the Youngers were racing thoroughbreds in Missouri, Louisiana, Texas and Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Their knowledge of racehorses also went back to their childhood. According to the March 26, 1874, Louisville Courier-Journal and the May 8, 1901, Chicago Tribune, their grandfather Charles Younger, who had moved his family to Crab Orchard, Ky., from Virginia, was a man ‘of wealth and sporting proclivities, owning stock, and of the anti-emancipation aristocracy.’ The family eventually moved to Missouri, where Charles’ son Henry Washington Younger married Bursheba Fristoe of Independence in 1830. The family home (and Cole Younger’s birthplace) was Big Creek, southeast of Lee’s Summit.

Sometime in 1869, according to an article in the March 27, 1875, Chicago Tribune, a horse race led to some trouble for Cole Younger in Louisiana, where he had lived for a time shortly after the Civil War and still had plenty of friends. Younger, according to the article, put every dollar he had — $700 — on his own horse, ‘one of the famous long-limbed, blue-grass breed of racers, an animal not fair to look upon but of great speed.’ Younger’s horse had a comfortable lead until someone came out of the crowd waving a cloth, causing the horse to lose its stride and finish second. When Younger refused to pay up, he found himself opposed by an angry mob. His response, according to the newspaper, was to draw two Dragoon revolvers and empty them into the crowd before dashing away. ‘Three of the crowd were killed outright, two died of their wounds, and five carry to this day the scars of that terrible revenge,’ the newspaper reported, adding that the deadly affair previously had been ‘apparently overlooked in the crimes attributed to [the Youngers] by the press.’ Whatever happened that day didn’t keep Cole Younger out of the state. According to a letter published in the November 30, 1874, St. Louis Republican, Cole claimed that he was in Louisiana’s Carrol Parish from December 1, 1873, to February 8, 1874, and thus could not have participated in three alleged James-Younger crimes — stagecoach robberies at Shreveport, La., (January 8, 1874) and Hot Springs, Ark., and the train robbery at Gads Hill, Mo. That March, the Louisville Courier-Journal ran an article stating that Cole and his brothers ‘all are good-looking, manly, and to a certain degree accomplished gentlemen. They would be accepted at any hotel or on any Mississippi steamer and hardly [be] taken for what they are — desperadoes without pity or fear.’ In short, the Younger boys, like the James brothers, had solid roots and were anything but antisocial loners. They were well educated and of aristocratic origin, with the manners of gentlemen. One of those gentlemen, John Younger, the brother of Cole, Bob and Jim, was killed by a Pinkerton Detective agent in a shootout near Monegaw Springs on March 17, 1874.

The James-Younger connection with Joseph Orville Shelby is well known. Born in Lexington, Ky., in 1830, Shelby was a boyhood playmate of John Hunt Morgan, who became a prominent Confederate raider in Kentucky. Shelby, whose family was related to the first governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby (1750–1826), rose to brigadier general in the Confederate Army. He served in every major Civil War campaign west of the Mississippi River, including the disastrous Missouri campaign in 1864. John Newman Edwards, whom he had befriended in Lexington, became his adjutant. Both Shelby and Edwards came to admire the courage of Frank James and the other Missouri guerrillas who were resisting Union forces. Frank was one of the guerrillas who saved General Shelby from capture on December 7, 1862, at the Battle of Prairie Grove, Ark. After Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered in April 1865, Shelby relocated to Mexico to offer his military services to Emperor Maximilian. Although Maximilian was soon shot by a firing squad, Shelby prospered in Tuxpan, Mexico. In 1867, he returned to Missouri, still a Confederate at heart. Almost certainly he harbored Frank and Jesse James when they were being pursued. Shelby owned 1,000-acre Travelers Rest, nine miles from Lexington, Mo., in Lafayette County, and he also owned 960 acres at Adrian in Missouri’s Bates County. He was one of the largest wheat growers and landowners in the state.

When Frank James went to trial in Gallatin, Mo., in August 1883 for his actions (he had allegedly killed passenger Frank McMillan) during the July 15, 1881, Winston, Mo., train robbery, Edwards was still urging in the newspapers for all to be forgotten and for Frank to be acquitted. And Shelby was still in Frank’s corner, testifying as a character witness for his old friend. Shelby said that he had seen Jesse James in November 1880 but hadn’t known that Jesse was wanted by the authorities. Shelby added, ‘The last time Jesse was at my house was at Page City, in the fall of 1881, where I saw Frank James in 1872, which was the last time I saw him.’ The lead prosecuting attorney, William H. Wallace, questioned Shelby about a waybill the old general had signed for Frank’s wife, Annie Ralston James, in the spring of 1881. Drunk at the time of his testimony, Shelby didn’t like that line of questioning and threatenedWallace. The next day, he apologized to the court for his earlier behavior, but Judge Charles H.S. Goodman still fined him $10. After court had finished, Shelby again tried to intimidateWallace, this time outside the courtroom.

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland appointed Shelby the U.S. marshal for the Western District of Missouri. Shelby died in office on February 13, 1897, at Adrian and was buried with full military honors in Kansas City’s Forrest Hill Cemetery on February 17. ‘Thousands of people lined the streets through which the procession passed,’ the Lexington Morning Herald reported the next day. ‘The sermon was preached by Rev. S.M. Neil of the Presbyterian Church and there was an address by Judge John Finis Phillips of the U.S. Circuit Court, a lifetime friend of the deceased.’ Judge Phillips had been part of the legal team at Frank James’ trial in Gallatin, and in 1915 he would give the eulogy at Frank’s funeral.

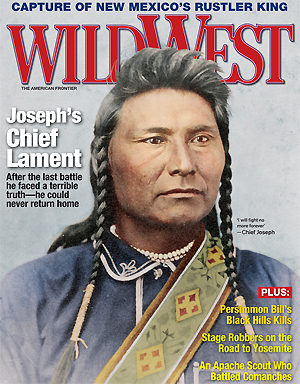

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

Far less well known is the James brothers’ connection with James H. Workman, a prominent resident of Union Township in Missouri’s Nodaway County. The parents of James Workman were among the first settlers of Nodaway, having migrated there from Indiana. James became a noted horse breeder, and his brother William was a wealthy landowner and respected citizen in the county. Although perhaps somewhat reluctantly, James Workman bought and dealt in blooded horseflesh with the James-Younger Gang, which paid him in $20 gold pieces. The gang sometimes camped in thick timber near Clear Creek, which bordered the Workman farm, west of Pickering. Four gang members, most likely Frank and Jesse James, Cole Younger and Clell Miller, may have been at that location before riding north into Iowa in early June 1871 to rob the Ocobock Brothers’ Bank in Corydon.

The gang’s inner circle of friends also included, to name a few, Howard County (Mo.) resident John McCorkle, an ex-guerrilla who had befriended Cole Younger and Frank James and later wrote Three Years With Quantrill; former Confederate Colonel Robert McCulloch, who lived near Boonville, where ‘The Great Cole Younger and Frank James Historical Wild West’ show performed on September 2, 1903; former Confederate Captain Warren Carter Bronaugh, a Missourian who worked hard to get the Younger brothers paroled from the Minnesota State Penitentiary at Stillwater; and, as mentioned earlier, the extended Hudspeth family of the ‘Six Mile Country’ (between Independence and Lake City) in Jackson County, Mo.

According to Through the Years With the Hudspeths, a three-volume family genealogy by Anna Ford, Major William Hudspeth had migrated to Missouri by 1828. He had been a soldier in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 and had founded Franklin, Ky. William was also considered a sportsman, bringing with him to Missouri a fine collection of foxhounds (the Hudspeth hounds later became famous, thanks to the efforts of a grandson, Thomas Benton Hudspeth). The major and his wife, Tabitha, whom he married in 1801, had 11 children — Nathan Beall, Thomas Jefferson, Sylvia, Joseph W., Missouri L., Silas Burke, Benoni Morgan, Joel Ephriam, George Washington, Robert Nichols and Malinda Paralee. The Hudspeth Settlement, as it was first known, was established at what is now Lake City, Mo. Robert Nichols ‘Bob’ Hudspeth, who never married, gave land for the small town. His house was about eight miles northeast of Independence. When he died in 1885, he owned 1,500 acres of land, which was being used for raising stock and farming. During the Civil War, Robert Hudspeth had served briefly with Quantrill, and Frank James was a good friend. Robert and brother Silas, who owned a 120-acre farm, supplied the James-Younger Gang with valuable horses and allowed their homes to be used as hideouts. Frank James’ only son, Robert Franklin (1878–1964), was named for Robert Hudspeth, according to descendant Joe Elsea, whose great-grandfather was Joel ‘Rufus’ Hudspeth (1839–1895).

Rufus Hudspeth was one of the children of Joseph W. Hudspeth, who had married his first cousin Amanda in 1830 and become a prosperous Jackson County farmer. After Amanda died in 1850, Joseph married Louise (Rice) Brown, and they had one more child — Joseph Lamartine (‘Lam’) Hudspeth. Rufus, who played with Frank and Jesse when they all were schoolboys, was one of several Hudspeths to serve in Quantrill’s guerrilla band, while other family members harbored the Rebel raiders. Rufus also later served under General Shelby and Maj. Gen. Sterling Price. After the war, Rufus went to Kentucky with Quantrill, but he returned to Missouri in 1865, married Sarah Franklin the next year, had four children — Joseph, Mary Amanda (Elsea), Elvira Beall (Chiles) and Charles B. — and became a prominent farmer and stockman. Rufus’ brother William Napoleon ‘Babe’ Hudspeth also served with Quantrill. After the war, Babe married Nannie Ragland of Independence and built a large two-story Victorian home that still stands in Lake City, which was then a thriving community with stockyards and a racetrack.

Other sons of Major William Hudspeth living nearby included George Washington Hudspeth and Joel Ephriam Hudspeth, who inherited the family farm. An 1877 history of Jackson County states: ‘It is probable that no finer nor a more extensive view of the surrounding country can be obtained than from the hill upon which the residence of Joel E. Hudspeth is located. It overlooks the Valley of the Blue. Its landscape is in its rural beauty.’ Many of the Hudspeths vacationed at Monegaw Springs, where James-Younger Gang members were known to hang out.

A strong connection between the gang and Hudspeths, if not already known by the authorities, became obvious from the testimony of former gang member James Andrew ‘Dick’ Liddil at the 1883 Gallatin trial of Frank James. Liddil, who once rode with Quantrill, had been part of Jesse James’ new gang, beginning with the October 8, 1879, train robbery at Glendale, Mo., and then had surrendered to the sheriff of Clay County on January 24, 1882. Liddil told the law most of what he knew about the gang, but his surrender was not publicized, so as not to alert Jesse James. The news didn’t become public until March 31. At his St. Joseph, Mo., home on the morning of April 2, 1882, Jesse read about it and supposedly commented that Liddil was a traitor who deserved to be hanged. Shortly thereafter, Bob Ford fired a shot heard around Missouri and beyond — the ball struck Jesse in the back of the head, killing the famous outlaw.

During his testimony at Frank James’ trial in 1883, Liddil said that after the Glendale train robbery, he, Jesse James and Ed Miller rode into the Six-Mile Country and went to Bob Hudspeth’s farm. From there, Liddil said he traveled about two miles to the 40-acre farm of Lamartine Hudspeth. Liddil had worked for Bob Hudspeth in 1870–75, and he testified in 1883 that he had lived at Bob’s ‘off and on for nine years.’ There, he added, he had become acquainted with John Younger and Jesse and Frank James, who often stayed around ‘a day or a night or two nights.’ Liddil told of the time he had been ‘riding a horse of Bob Hudspeth’s, which I had [taken to] Lake City for the purpose of running a race.’ He ran two heats before he was chased from the area by Deputy Marshal Ed Lee. Liddil then returned to Bob Hudspeth’s home to put the horse in the stable. From there, Liddil’struck out on foot, and next day went to Ben Murrow’s [place], who knew I was dodging the officers, and bought a horse from him in trade.’ Ben Hudspeth Murrow’s mother was Major Hudspeth’s oldest daughter, Silvia. During the war, Ben had served under General Shelby and had later joined Quantrill. Liddil also said that in 1879 he met with Jesse James, Wood Hite, George Hite, Ed Miller, Daniel ‘Tucker’ Bassham and Bill Ryan at Murrow’s 56-acre home (built by the Hudspeths in 1830) west of Buckner, Mo. Ben Murrow would be a pallbearer at the 1882 funeral of Jesse James and the 1915 funeral of Frank James.

Lamartine Hudspeth (1858–1915) also received further mention in Liddil’s testimony. Liddil said that he bought a chestnut sorrel horse from Lamartine before the Winston train robbery on July 15, 1881. Lamartine lived in Lake City, but he owned a beautiful racing stallion named John Morgan and he attended horse races at Louisville and New Orleans. In The Complete and Authentic Life of Jesse James, Carl Breihan noted that a fresh horse was always waiting for Jesse at the Hudspeth stable. ‘On some mornings when Lamartine went out to the barn,’ Breihan wrote, ‘the fresh horse was gone and standing in its place was a tired animal that Jesse [or Frank] had left.’ After Jesse James was killed, Lamartine Hudspeth was one of the people called upon to identify the body. Lamartine later ran into his own serious trouble with the law. On November 25, 1899, he went on trial for killing Joe Kesner, a married railroad station agent who had apparently been showing too much interest in Lamartine’s niece. Lamartine’s attorney was Arthur N. Adams, considered the best in Jackson County at the time, and Lamartine was acquitted.

The Hudspeths sometimes bred their horses with the horses of another prominent Jackson County family, the Chiles. Jim Crow Chiles and Kit Chiles were both members of Quantrill’s raiders, while William Chiles was an early member of the James-Younger Gang. Bill Chiles was one of the men suspected of holding up the Clay County Savings Association bank in Liberty, Mo., on February 13, 1866. Although Jim Crow Chiles may never have ridden with the James boys, he became involved in a dispute with gang member and ex-guerrilla Payne Jones, whom he caught stealing a valuable horse from him before the gang robbed the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin on December 7, 1869. Jim Crow’s name also surfaced after the ticket booth at the Kansas City Exposition was robbed on September 26, 1872. Jesse James was one of the accused men, prompting him to write a letter to the Kansas City Times in October, denying his involvement. Among other things, Jesse wrote: ‘It is generally talked about in Liberty, Clay County, that Mr. James Chiles, of Independence, said that it was me and Cole and John Younger that robbed the gate, for he saw us and talked to us on the road to Kansas City the day of September 26th. I know very well that Mr. Chiles did not say so, for he has not seen me for three months, and I will be under many obligations to him if he will drop a few lines to the public, and let it know that he never said such a thing.’ Jim Chiles did respond with a letter, in which he denied seeing Jesse or the two Youngers on or near the date of the robbery. That November, Cole Younger wrote a letter to the St. Louis Republican denying his own involvement, but in detailing his movements on the day of the robbery, he said he had had a long talk with Chiles at the Big Blue River and had spent the night at Silas Hudspeth’s place in Jackson County. Bill Chiles’ son, Ike, was in the Saddlebred business for many years. One horse bred by the Chiles family was known as Jesse James’ Mare. They also bred the Saddlebred mare Mary Low, whose sire was Lamartine Hudspeth’s stallion John Morgan.

After Jesse James was killed, the Hudspeths continued to support Frank James. Frank’s 1883 murder trial in Gallatin, Mo., lasted 16 days, and he was acquitted after the jury deliberated for 3 1/2 hours. Because Dick Liddil had implicated Frank in the March 11, 1881, holdup of a paymaster in Muscle Shoals, Ala., Frank also stood trial in Huntsville, Ala. That trial lasted 10 days in April 1884, and again Frank was declared not guilty. Once back in Missouri, he faced charges for the July 7, 1876, train robbery at Otterville, because a captured gang member, Hobbs Kerry, had fingered him long ago. However, just two days before the trial was scheduled to begin in Kansas City in February 1885, the case was dropped because evidence was missing and there were no living witnesses available. Frank James was now clear of all charges in Missouri, and newly elected Governor John Sappington Marmaduke, a onetime Confederate general, had no intention of turning the former guerrilla over to Minnesota authorities to stand trial for the Northfield robbery. Marmaduke, according to newspaperman Edwards, had merely advised Frank to go to work on a farm and ‘to keep out of the newspapers. Keep away from fairs and fast horses, and keep strictly out of sight for a year.’

Over the next 30 years, Frank James would continue to be welcome whenever he made a visit to one of the Hudspeth homes in Lake City. On January 8, 1897, the former outlaw was in St. Louis when he wrote a letter to Mrs. Malinda Paralee Hudspeth Wood, the youngest daughter of Major William Hudspeth:

Dear Friend, I have just received your favor. It grieves me more than you can imagine to learn of the death of my dear friend. I am anxious to visit the old place before you leave it, from the fact that around that hospitable home of yours, many fond recollections are recalled and were it possible to turn back memories page and live over those happy days again, that big fire in the west room and around it seated Joel, Silas, Robert, George, Rufus, Babe, Lamartine, Ben Murrow and the others would be a picture that would gladden the heart of all. But as this cannot be, I hope that when I do come, I will have the pleasure of meeting all those that are living around that same dear old hearth. It will not be so very long before the restless flapping of death wings will no doubt be heard around the persons of many more of our dear friends and so on down to the end of time, one generation after another. My sympathy goes out to you in this dark hour and I trust you will be given courage by the Supreme ruler to bear this burden — as He gave you courage and strength to do so on other occasions. We will give you due notice in advance of what time we will be at your home. Present my regards to Ben, Babe, Lamartine, Uncle George, in fact to all our friends. Mrs. James also joins me in love to all. I am yours most respectfully, Frank James.

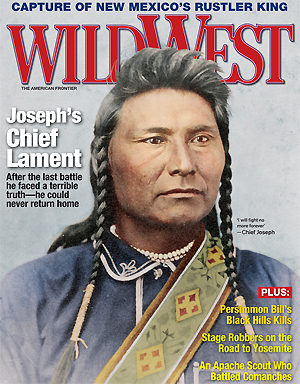

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Read More in Wild West Magazine

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

George Hudspeth died six years after the letter was written. Babe Hudspeth died in 1907. Malinda Paralee, to whom Frank wrote the 1897 letter, died in 1913, two years before Lamartine Hudspeth and Frank James himself died. Ben Hudspeth Murrow lived until 1916, as did Cole Younger. During their criminal careers and afterward, the James and Younger brothers had an inner circle of good friends, and few were better than the Hudspeths, faithful to the end.

This article was written by William Preston Mangum II and originally appeared in the August 2003 issue of Wild West magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!

Featured Article

When the James Gang Ruled the Rails

Liberty, Missouri has a nice ring to it and will no doubt be remembered for as long as folks recall the Wild West’s most famous anti-establishment rebels–the James (or James-Younger) Gang. It was on February 13, 1866, that at least a dozen former Southern guerrilla soldiers, including Frank James and Cole Younger, held up the Clay County Savings Association in Liberty. Jesse James was recovering from wounds suffered as a Confederate guerrilla and probably wasn’t able to help brother Frank and Cole, but the Liberty bank job is considered the James-Younger Gang’s first robbery.

Adair, Iowa, might not have the same ring to it, but it was there on July 21,1873, more than seven years after the Liberty holdup, that another James-Younger first occurred–the gang’s first train robbery. Using their wartime guerrilla skills–riding and shooting and eluding the enemy–the boys may have robbed as many as nine banks before they got around in 1873 to tapping into this new, lucrative source of treasure, the railroad industry.

Actually, the James brothers and the Younger brothers were not the first post-Civil War train robbers in the country. Another set of brothers, the Renos, had held up an Ohio & Mississippi passenger train near Seymour, Ind., in October 1866. The Reno Gang struck again in May 1868 at Marshfield, Ind., but its third attempt at a train robbery bombed that July outside Brownstown, Ind. Within two years of the Renos’ first train robbery, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, with help from local vigilantes, had destroyed the gang.

Apparently no outlaw gang was strong enough or bold enough during the next five years to take on the railroad industry. But the railroads were routinely transporting millions of dollars in gold, silver and greenbacks, and even though the Jameses and the Youngers had made out quite well robbing small-town banks, they must have envisioned greater profits by stopping trains. In any case, by the summer of 1873, they were ready to attempt the first train holdup west of the Mississippi. Such a robbery did have a few advantages over bank jobs. They could stop a train at a point of their own choosing, and by destroying the nearest telegraph office to delay news of the robbery, they would not have to immediately contend with a posse. Also, they would have the element of surprise working for them–at least the first time.

The trouble with train robberies, especially after the James-Younger Gang reinitiated them wholesale, was that the railroads put armed guards on their trains and kept the schedules for their big shipments of bullion and currency a secret. For that reason, the gang found it necessary to spy on the railroads for information about valuable cargoes and accompanying guards. When the famous Missouri outlaws struck at Adair, they started a veritable war with the powerful railroads and their detectives.

The James-Younger Gang’s first train robbery did not come close to matching the monetary haul of its first bank robbery. In fact, the $60,000 taken at Liberty was most likely more money than was collected in any of the gang’s later robberies. The previous year, Confederate soldiers had robbed a bank in St. Albans, Vt., but the heist in Liberty is considered the first successful peacetime daylight bank robbery in U.S history.

Liberty only seemed to whet the gang’s appetite for loot. Within 15 months, three more banks in Missouri were held up, though Jesse and Frank James may not have participated in any of those robberies. The James boys, as well as Cole Younger, most likely did rob a bank in Russellville, Ky., in March 1868. After a bank holdup in Gallatin, Mo., in December 1869, the Jameses became the chief suspects in that and other crimes. As the gang fled Gallatin, Jesse James was unseated from his horse and forced to double up on Frank’s horse. Later, the fine-blooded horse left behind was recognized as belonging to Jesse James of Kearney, Mo. The James-Younger Gang went on to rob banks in Corydon, Iowa; Columbia, Ky.; and Ste. Genevieve, Mo., before it got around to working on the railroads.

In July 1873 the gang learned of a big gold shipment being sent by rail from Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. The outlaws–now probably including Cole Younger’s brothers Jim, John and Bob–planned to strike the eastbound Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific train outside Adair, Iowa, and rode into that town about July 18. Posing as businessmen, they picked up information about the train schedule and also explored the rails. On July 21, they were camped near a blind curve along the line. Before dark, according to the Leavenworth Daily Times, they pulled up several railroad spikes holding down a rail on one side of the curve. They then hitched a large rope around the end of the loosened track and waited. At dusk, they heard the loud puffing of a steam locomotive approaching their position. As the ground trembled under their feet, the bandits tugged at the rope, pulling the rail inward and out of alignment.

Aboard the train, engineer John Rafferty peered down the track through the twilight, alert as he entered a sharp curve in the line. Then there were shots, and a bullet tore through the engineer’s right thigh. Rafferty threw the engine into reverse, but it was too late. His engine lurched off the track, crashed into a ditch and toppled on its side, breaking his neck. The fireman, Dennis Foley, was badly burned but survived. A towering cloud of steam and smoke spewed from the wrecked locomotive. Wearing masks, the outlaws quickly approached the stalled cars. They broke into the U.S. Express Company’s safe but found only about $2,000. According to the Daily Times, 3 1/2 tons of gold and silver bullion was also on the train but was apparently too heavy for the outlaws to carry away. (Later accounts of the robbery maintain that a following train carried the bullion.) Disgusted, the bandits moved among the passengers, lifting wallets, jewelry and valuables before they took off, heading south.

The outlaws’ trail led straight into Missouri. Several people in the area of the robbery said that two of the outlaws looked like Frank and Jesse James. In response, on December 20, 1873, Jesse James wrote the St. Louis Dispatch from Deer Lodge, Montana Territory, denying the brothers’ complicity in that and other crimes. If Missouri Governor Silas Woodson would promise them protection, Jesse wrote, ‘we can prove before any fair jury in the state that we have been accused falsely and unjustly. The protection would be from a mob, or from a requisition from the Governor of Iowa, which is the same thing.

Just over a month after that letter was written, the James-Younger Gang targeted a train at Gad’s Hill, Mo., a flag stop 120 miles south of St. Louis on the Iron Mountain Railroad line. About 4:45 p.m. on January 31, 1874, five bandits armed with Navy Colt revolvers and double-barreled shotguns captured the stationmaster and flagged down the Little Rock Express. Conductor C.A. Alford later described the outlaws to a St. Louis Republican reporter as tall men dressed in Federal Army overcoats and wearing white cloth masks with holes for eyes and nose. One of the bandits had grabbed Alford by the collar and told him, Stand still or I’ll blow the top of your head off! The passengers, who were gaping out the windows, were warned that if anyone fired a gun, the conductor would be killed.

Boarding the train, the bandits relieved the 25 passengers of their money and jewelry, preying especially on what they scornfully called the plug-hat gentlemen. Each male passenger was asked tauntingly if he was Mr. Pinkerton, whom the outlaws said they wanted. After rifling the mailbags and robbing the Adams Express safe, one of the bandits, thought to be Jesse James, handed engineer William Wetton (or somebody else, accounts differ) a whimsical press release titled A true account of this present affair. It stated: The most daring robbery on record. The southbound train on the Iron Mountain Railroad was stopped here this evening by five heavily armed men and robbed of___dollars….The robbers were all large men, none of them under six feet tall. They were masked, and started in a southerly direction after they had robbed the train, all mounted on fine-blooded horses. There is a hell of an excitement in this part of the country! (Jesse had conveniently allowed for the railroad to fill in the amount lost, but apparently that was never done.) A 25-man posse formed the next day but was unable to follow the outlaws’ trail.

The first train robbery in Missouri had gone off seemingly without a hitch–nobody had been killed at Gad’s Hill, and the outlaws had enjoyed themselves. However, because registered mail had been taken, the Pinkertons were immediately called in to track down the robbers. Pinkerton agent John W. Whicher arrived at Liberty on March 10, 1874, and consulted with D.J. Adkins, president of the local Commercial Bank, and O.P. Moss, a former sheriff, about his plans. He told them that he intended to obtain a farmhand’s job at the Samuels’ farm (the farm of the Jameses’ stepfather and the boys’ hangout). When the opportunity was ripe, he said, he would capture the outlaws. Both of the local men cautioned Whicher against such a bold plan. Moss told him, The old woman [the James boys’ fiery mother, Zerelda] would kill you if the boys don’t. The cocky 26-year-old detective would hear no more. After getting directions to the Samuels’ farm, Whicher dressed up as a farm laborer (though he was described as having a tender complexion and hands like a city fellow) and, at 5:15 p.m., boarded a slow freight taking him to within four miles of the farm. Unfortunately for Whicher, the James boys had already been alerted, most likely by banker Adkins. Whicher’s body was found the next morning, south of the Missouri River near Independence, Mo. He had been shot through the head and heart, and a rope dangled from his neck.

Meanwhile, two other Pinkertons were hot on the trail of the Youngers in St. Clair County. On March 15, 1874, agents Louis Lull (using the name W.J. Allen) and James Wright (also known as John Boyle)–accompanied by a part-time deputy sheriff from Osceola, Mo., Edwin B. Daniels–set out from Osceola for Roscoe. After staying at the Roscoe House hotel that evening, the three left the next afternoon for the farm of Theodrick Snuffer, a family friend of the Youngers, some three miles out of town. Wright fell back out of sight as Lull and Daniels approached the farmhouse. Snuffer came out to talk to the two men, who posed as cattle buyers. John and James Younger watched the exchange from Snuffer’s attic. The two strangers in the yard were well armed and suspicious looking. When they departed to rejoin Wright, the two Younger brothers followed them.

When the Youngers were within shouting distance of Lull, Wright and Daniels, John Younger ordered the trio to halt. Wright panicked and put spurs to his horse. Jim Younger fired at him, shooting his hat off, but Wright kept on going. Lull and Daniels turned around slowly in the road. The Youngers told the two cattle buyers to throw down their guns and then questioned them about what they were doing in this part of the country. Rambling around, Lull replied. An argument ensued, and John Younger leveled his shotgun at Daniels. Lull saw his chance. He pulled a No. 2 Smith & Wesson from inside his coat and shot John Younger in the neck. Recoiling, the wounded Younger fired both barrels of his shotgun at Lull, striking him in the left arm. Lull’s horse now bolted eastward, with John Younger in pursuit. As Lull attempted to regain his reins, John rode beside him and fired twice, one of the bullets tearing into Lull’s left side. The detective’s horse then charged into a thicket, where a low limb stripped Lull from the saddle. Meanwhile, John turned back toward his brother, rode a few yards, and tumbled into the road dead. By that time, Jim Younger had killed Daniels and had received a flesh wound in his hip. The seriously wounded Lull was taken to Roscoe later that evening, but he died within six weeks.

The deaths of Whicher and Lull enraged William Pinkerton, head of the detective agency, and the Pinkertons began accusing the gang’s Missouri friends of harboring and supporting the outlaws. Newspapers debated the issue. Missouri Governor Woodson hired secret agents J.W. Ragsdale and George W. Warren to aid in the outlaws’ capture. None of these developments kept Jesse James from marrying his cousin Zee Mimms in Kearney in late April 1874 after a nine-year courtship, or Frank James from eloping with Anna Reynolds Ralston that June.

By December 1874, the James boys and two of the surviving Youngers, Cole and Bob, were ready to rob their third train. After learning of a huge gold shipment from the west, five gang members forced section hands to pile ties on the tracks of the Kansas Pacific Railroad near Muncie, Kan., on December 8. Then, using a red scarf, the outlaws flagged down an express train and stole at least $30,000, perhaps as much as $55,000. During the holdup, shots were fired at the conductor as he ran from the train, apparently to flag a freight train that was following the express. He was not hit. In response to this latest outrage, the Kansas Pacific Railroad Co., the governor of Kansas and the express company together promised at least $10,000 for the capture of the robbers, dead or alive. The suspects included Jesse and Frank James, of course, but only one man, Bud McDaniel, was ever captured and charged with the crime. McDaniel never confessed or squealed on anyone; he escaped jail before he could be tried and was soon after shot and killed while being pursued.

On January 26, 1875, the Pinkertons pursued their most desperate solution to capturing the James brothers. That night, a special train eased out of Kansas City, Mo., carrying a team of heavily armed detectives and their horses and gear. Conductor William Westfall let them off near Kearney and then returned with the train to Kansas City. The detectives rode to the Samuels’ farm, where they sent a cast-iron ball filled with flammable fluid crashing through the window of the Samuels’ parlor in a shower of fire and glass. Reuben Samuel, Frank and Jesse’s stepfather, rushed into the room and, fearing the house would go up in flames, kicked the flaming ball into the fireplace. A tremendous explosion rocked the house, mortally wounding 9-year-old Archie Peyton Samuel (Jesse and Frank’s half brother), mangling Zelda Samuel’s right arm (which later had to be amputated at the elbow), and wounding her black servant. The detectives left as abruptly as they had come, without even summoning a doctor. A neighbor of the Samuels family, James A. Hill, rushed to Kearney and brought back Dr. James V. Scruggs, but there was nothing the doctor could do for young Archie.

Exactly what happened during the raid is unclear, and it has been debated whether the object thrown was intended as a bomb or a flare. Likely, at least one of the outlaw James boys had been in the house, for later someone borrowed Dr. Scruggs’ horse to escape from the area. There was also talk that some of the detectives had been killed, but that was never verified. What is clear is that a revolver left behind by the detectives bore the inscription P.G.G. (Pinkerton Government Guard). That organization, however, refused to accept responsibility for the attack.

In March, a Clay County grand jury found murder indictments against Robert J. King; Allan K. Pinkerton, William Pinkerton’s son; Jack Ladd, a Pinkerton spy who worked at Daniel Askew’s farm, next to the Samuels’ place; and five other men. But no one was ever arrested. Many at the time believed that high-placed officials in the Missouri government prevented the arrests to protect themselves, the Pinkertons and the railroads. Ultimately, so much public sympathy was aroused for the Jameses because of the debacle that a move was made in the Missouri Legislature to provide amnesty to the James Gang. While the vote was 58 to 38 in favor of amnesty, the measure still failed because a two-thirds majority was needed. In the meantime, the James brothers dispensed their own justice. John Askew, the Samuels’ neighbor who had hired the Pinkerton spy, was gunned down in front of his house on the night of April 12, 1875. That September, a bank was robbed in Huntington, W.Va., that may have involved the James-Younger Gang (see story in December 1998 Wild West).

The James-Younger Gang renewed its attacks against the railroads on July 7, 1876, when it struck a Missouri Pacific train at a site known as the Rocky Cut, near Otterville, Mo. Riding out of heavy woods, the gang seized Henry Chateau, a watchman guarding a railroad bridge under construction, and his red lantern was used to signal the incoming train to halt. As the train squealed to a stop, discharging pistols and terrific yells rang out, accord-ing to the Kansas City Evening Star. John B. Bushnell, the chief messenger, fled to the other end of the train with the U.S. Express safe key. Once inside the baggage car, the outlaws held a gun to the head of baggage master Louis Pete Conklin (sometimes referred to as Conkling) and forced him to lead them in search of Bushnell. As the masked bandits proceeded through the train, women shrieked and men scrambled beneath their seats. After finding Bushnell and threatening him with death, the outlaws retrieved the key and opened the safe. They then obtained the engineer’s coal pick and broke into the Adams Express safe. From the two safes the bandits gathered more than $15,000, which they stuffed into the gang’s signature two-bushel flour sack. A small posse soon formed but had no luck–the hard-riding gang was long gone.

The railroad and express companies responded by persuading Chief of Police James McDonough of St. Louis to send his agents into southwest Missouri to chase down the criminals. In turn, McDonough enlisted the help of Larry Hazen, a well-known detective from Cincinnati. This effort led to the arrest of inexperienced gang member Hobbs Kerry, who had been flashing money in Granby, Mo. Told there were witnesses who recognized him from the Otterville robbery, Kerry broke down and confessed, naming as his accomplices Jesse and Frank James, Cole and Bob Younger, Charlie Pitts, Bill Chadwell and Clell Miller. A case was now building against the gang–if it could be captured. Jesse James continued to write disclaimers to newspapers, calling Kerry’s confession a well-built pack of lies from beginning to end in one letter published in the Kansas City Times in August. The Kansas City Journal described the letters as suspiciously–almost nauseatingly–monotonous. Cole Younger later wrote that Kerry’s implication of the Jameses and Youngers convinced the gang members to make one haul, and with our share of the proceeds start life anew in Cuba, South America or Australia.

The next month, the gang was changed for all time when the Jameses and Youngers not only went back to robbing a bank but also chose a bank far from their usual stamping grounds. The aborted robbery of the First National Bank of Northfield, Minn., on September 7, 1876, took the Youngers out of the James-Younger Gang. Cole, Jim and Bob Younger were all captured and sent to prison in the aftermath of that fiasco, which had also cost the lives of Pitts, Chadwell and Miller. Jesse and Frank James escaped, but now they had to recruit new men. After Northfield, the notion that the James boys were being accused of robberies that they had not committed played poorly in Missouri. The gang of ex-Civil War guerrillas having problems with postwar adjustment had become a gang of common thugs in the eyes of many disenchanted Missourians. Outsiders now called Missouri the Robber State and an Outlaw’s Paradise, and lawmen increasingly targeted the gang.

The James brothers were not heard from for months after escaping from Minnesota, but they had not gone to South America or Australia. More likely they had spent time with family in either Texas or Kentucky. By the summer of 1877, they had moved to Tennessee, where Frank adapted to the quiet life better than his younger brother. In need of money and perhaps excitement, too, Jesse recruited new gang members and took on the railroads again, this time without Frank.

The new James Gang struck on October 8, 1879, at Glendale, Mo., a little station on the Chicago & Alton line 15 miles east of Kansas City. The outlaws abducted at gunpoint a handful of Glendale citizens, the stationmaster and the telegraph operator. After smashing all of the station’s telegraph equipment to prevent outside knowledge of the robbery, they ordered the telegraph operator to lower the green light (a signal to the conductor to stop the train for further instructions). When the operator refused, the muzzle of a gun was shoved into his mouth and he weakened, according to a Kansas City Times reporter.

To ensure that the train stopped, the robbers also covered the tracks with stones.

At 8 p.m., Jesse and company halted the eastbound train and fired enough shots to keep the passengers inside. The express messenger, William Grimes, filled a satchel with money from the U.S. Express Company’s safe and tried to escape out the back of the express car. Anticipating this move, a gang member intercepted Grimes and struck him on the back of the head with the butt of a revolver, knocking him unconscious. Some 30 minutes later, the outlaws rode off uttering wild whoops of exultation, according to one account. Estimates of the take ranged from $6,000 to as much as $50,000.

Jesse James returned to Nashville after the Glendale robbery, but he was heard from twice in September 1880 in Kentucky–holding up a Mammoth Cave tourist stage and then a Dovey Cove Mine payroll in Mercer. Jesse had a nice haul at Muscle Shoals, Ala., on March 11, 1881, when he robbed paymaster Alex Smith of $5,000. But things took a downturn two weeks later when one of his gang members, Bill Ryan, was arrested in Tennessee. Ryan was eventually convicted for his role in the Glendale train robbery after another of Jesse’s recruits, Tucker Basham, testified against Ryan in Missouri. Basham also mentioned Jesse James as an accomplice, which caused James confederates to burn Basham’s Jackson County home. Basham fled the area.

The James Gang wasn’t through with trains yet. In fact, Frank James returned to contribute his expertise. On the evening of July 15, 1881, a Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific train stopped at Cameron, Mo., and was boarded by two gang members wearing dark suits of clothes [and] high caps, according to the Kansas City Evening Star. A few miles to the northeast, at Winston, Jesse and Frank James and their cousin Wood Hite boarded the train and put on masks. As the train proceeded, William Westfall, the same conductor who had brought the Pinkertons to the Samuels’ farm back in January 1875, collected fares in the smoking car. Suddenly, a tall man with black whiskers and wearing a linen duster (probably Jesse James) yelled, Stop! and ordered the conductor to raise his hands. Instead, Westfall crouched and raced for the back of the car. One of the bandits then shot him in the back. Westfall reeled onto the back platform and tumbled dead off the moving train. The bandits then cut the bell rope, signaling the engineer to stop the train.

Meanwhile, gang members Dick Liddil and Clarence Hite, another James cousin, fired into the locomotive, shattering its windows and ensuring that the engineer pulled onto a siding at Little Dog Creek Bridge. As the outlaws robbed the express car, a curious passenger, Frank McMillan, gaped at them from the platform. A bandit shot him in the head, and McMillan rolled from the train. In the express car, bandits had pistol-whipped the two messengers and robbed the express safe. Exactly how much money was taken is uncertain. The Kansas City Evening Star on July 16 called the crime the most daring, reckless, and cold-blooded murder and robbery ever enacted in the country. Liddil later confessed to participating in the Winston train robbery and said that Jesse shot Westfall and Frank shot McMillan.

Missouri Governor Thomas Crittenden was determined to stop the James Gang once and for all. The governor was under considerable pressure, since Missouri was trying to cast off its reputation as the Robber State. With the aid of Colonel Wells H. Blodgett, attorney for the Wabash Railroad, he called a meeting of railroad and express company executives in St. Louis on July 26, 1881. The officials promised to pay $5,000 each for the delivery of Frank and Jesse James. Another $5,000 each would be offered for their convictions.

The James Gang was not quite done. On September 7, 1881, exactly five years after the failed bank robbery in Northfield, the outlaws stopped a Chicago & Alton train where the tracks ran through Blue Cut, some two miles west of Glendale. Along with Jesse and Frank, participants likely included Clarence Hite, Dick Liddil and a new recruit, Charlie Ford. They used a red lantern to get the train to stop, broke open the express car and struck messenger H.A. Fox with a pistol butt. The gang leader not only didn’t wear a mask but also announced that he was Jesse James. Engineer Choppey Foote later said that the bandits took all the money they could but that the leader gave him $2 to use to drink the health of Jesse James tomorrow morning. The outlaws collected $1,000 at most, as well as jewelry. They made a clean getaway, but there would be no more robberies for the James Gang.

In February 1882, Clarence Hite was arrested in Kentucky and extradited to Missouri, where he pleaded guilty to involvement in the Winston robbery and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Another cousin of the Jameses, Wood Hite, died early that same year at the hands of Dick Liddil and Bob Ford, Charlie Ford’s younger brother. Apparently, both Liddil and Wood Hite had been vying for the attentions of the attractive widow Martha Bolton, the sister of the Ford brothers. Liddil turned himself in and told all he knew about the James Gang’s robberies.

On Monday, April 3, 1882, Bob and Charles Ford were visiting with Jesse James in his St. Joseph, Mo., home when Bob shot the famous outlaw in the back of the head. Two weeks later, the Fords were indicted on murder charges, found guilty and sentenced to hang. Governor Crittenden granted them full pardons that very afternoon. Many people assumed there had been a conspiracy involving the governor to eliminate Jesse James. In a letter to the Missouri Republican that he supposedly wrote in February 1884, Bob Ford said that he had not been hired by Crittenden or anyone else.

On October 5, 1882, Frank James, with no desire to return to outlawry and fearing the same treatment as Jesse, personally surrendered to Crittenden in Jefferson City. Frank’s wife later said that her husband could not even cut a stick of wood without looking around to see if someone was slipping up behind him to kill him.

In August 1883, Frank James stood trial for the murder of train passenger Frank McMillan during the 1881 Winston robbery. Frank’s star-studded troop of lawyers got him off, overcoming the testimony of a gang member turned informer, Dick Liddil. They got a boost from the governor himself, who testified that Liddil initially told him that Jesse James was the one who had shot McMillan. Furthermore, in February 1884, Crittenden dismissed all other charges against Frank James in Missouri.

That April, Frank did have to stand trial in Alabama for the 1881 Muscle Shoals robbery, but he was found not guilty. By the middle of 1884, 41-year-old Frank James could begin to pursue honest work under his real name. The first bank robbery at Liberty in 1866 and that first train robbery at Adair in 1873 no doubt were impossible to forget, but at least they could now be dusty, distant memories for Jesse’s big brother.

This article was written by Donald L. Gilmore and originally appeared in the August 2000 issue of Wild West magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!