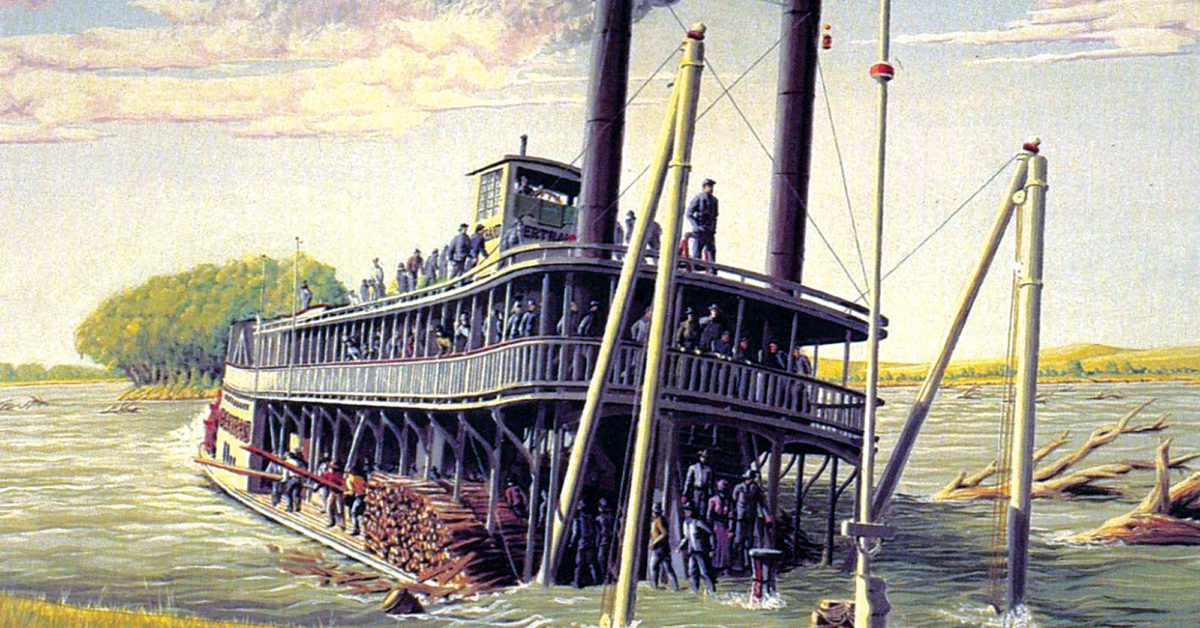

In the frontier West of the mid- to late 1800s the cutting-edge method of travel, both commercially and privately, was the steamboat. The continental United States is blessed with excellent waterways, none grander than its two mightiest rivers, the Missouri and the Mississippi. While the Mississippi wends a relatively languid and gentle course, the Missouri has earned its reputation as an unpredictable and sometimes hazardous body of water.

American Indians were undoubtedly first to ply the Missouri by boat, but it was the big 19th century fur companies, principally John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Co., that initiated the first large-scale attempts to conduct commercial and passenger transportation along the Missouri. The benefits of a steamboat for transporting trade goods to the forts on the upper Missouri were manifold. Fur trader Pierre “Cadet” Chouteau Jr. spelled out some of those in advantages in an Aug. 30, 1830, letter to American Fur headquarters in New York:

Since the loss of our keelboat [Beaver] and the arrival of Mr. [Kenneth] MacKenzie [American Fur’s principal trader], we have been contemplating the project of building a small steamboat for the trade of the upper Missouri. We believe that the navigation will be much safer in going up, and possibly also in coming down, than if it is by keelboat.…I imagine that there will always be a little risk to run, but I also believe that if we succeed, it will be a great advantage to our business.

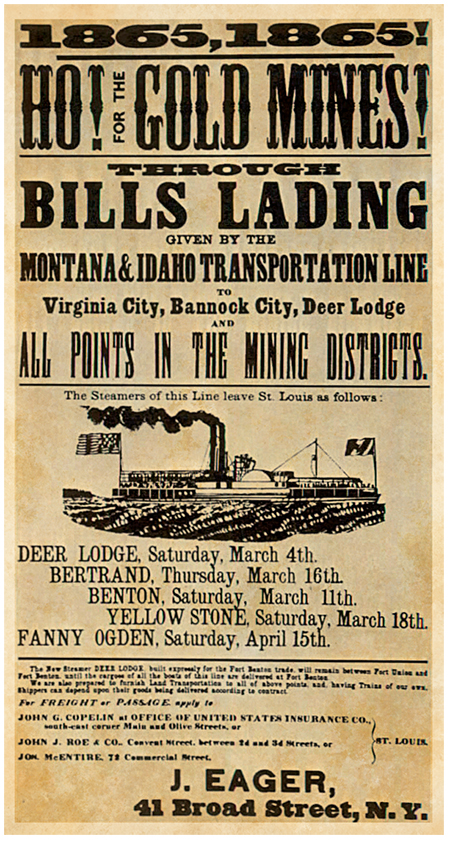

In July 1831, on its maiden voyage out of St. Louis, American Fur’s side-wheel steamboat Yellowstone completed the first successful commercial run of the upper Missouri, navigating past its many hazards as far as the Dakotas and back. The following year it steamed some 2,000 miles upstream to the mouth of its namesake river. Three decades later myriad steamboat companies and business concerns were utilizing the river as a superhighway west for the transport of goods, livestock and passengers. Major gold strikes in what would become Montana necessitated the import of mining equipment, sturdy clothing and vast stores of dry goods. The quickest and most cost-efficient shipping method was by steamboat. The 161-foot paddle wheeler Bertrand was typical of those in operation on the Missouri in 1865, as touted in an ad from the February 9 edition of Daily Missouri Republican:

The new fast and light draught steamer Bertrand…will leave St. Louis for Fort Benton on the opening of navigation to Omaha. Shippers and passengers seeking transportation to Fort Benton, Virginia City, Deer Lodge and the Bitterroot Valley cannot improve this opportunity.

Though such ads promised passengers safety, travel on the Missouri was fraught with danger. The main channel was also known to shift widely, and shoals and sandbars could pop up in unexpected spots between voyages. Submerged fallen trees, known snags or sawyers, were particularly hazardous, as they were essentially undetectable until a vessel hit one, often resulting in costly repairs or even the loss of the vessel. The boilers on these steam-powered vessels could, and sometimes did, explode, resulting in the destruction of the vessel and/or deaths of passengers and crew. In an 1897 study noted engineer and historian Hiram M. Chittenden recorded the loss of 295 steamboats on the Missouri from the 1831 outset of commercial river traffic. The majority of losses were due to snags (193), while other boats succumbed to river ice (26), fire (25), submerged rocks (11), collisions with bridges (10) and the dreaded boiler explosions (six), among other causes.

Thus, trusting passengers and shippers placed their fates in the hands of chance when Bertrand departed St. Louis at 10 a.m. on Saturday, March 18, 1865, bound for the upper Missouri. Launched a year prior, the steamboat was owned by the St. Louis–based Montana & Idaho Transportation Line, founded by experienced steamboatman John J. Roe, son-in-law John G. Copelin and partners. The partners already owned a wagon freighting line and hoped to increase their share of the upriver trade with a large shipment of dry goods and supplies for the mining camps in Montana Territory. Stowed aboard with their shipment was a cargo of various consigned goods also intended for the goldfields. Among the consignees was “Mr. Montana” himself, the pioneering Granville Stuart, who operated a mercantile store in Deer Lodge that supplied miners. Stuart and the owners of Bertrand, as well as the passengers, were all in for a shock. The ship never reached its destination.

On April Fools’ Day Bertrand was proceeding up the Missouri past De Soto, Neb., some 25 miles upstream of Omaha, when it hit a snag. Fortunately for the passengers and crew, the wreck occurred in daylight, the weather was mild, the boat took 10 minutes to sink, and no one died. The next afternoon Bertrand’s master, Captain James A. Yore, and several passengers checked in at Omaha’s prestigious Herndon House hotel.

Among the items initially salvaged from Bertrand were goods labeled for Stuart and other consignees. Later reports and rumors also claimed the doomed steamship had been carrying a fortune in mercury (aka quicksilver, used to refine gold), as well as 5,000 gallons of whiskey in oaken casks. A report in The Omaha Daily Bee dated July 19, 1896, more than 30 years after the wreck, related the efforts of four would-be salvors and a hired civil engineer to locate Bertrand and salvage the rumored 35,000 pounds of mercury aboard. They appear to have failed, as the salvage operation vanished from the public record.

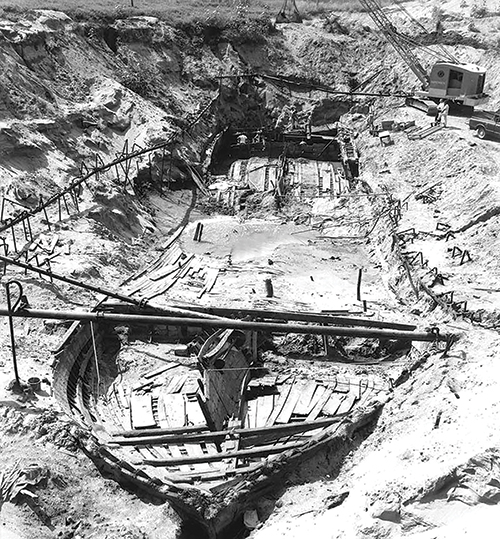

The next serious attempt came 72 years later when Omaha-based treasure hunters Jesse Pursell and Sam Corbino went in search of Bertrand. On scouring period newspaper accounts, the pair had discovered the name of someone who had owned land along the Missouri near the wreck site. They correctly reasoned that over the decades the river had shifted its course, leaving Bertrand buried beneath a certain field. In 1968, having narrowed their search and obtained the permission of the current landowner, the salvors used fluxgate magnetometers to scan for buried ferrous metals, such as those contained in the cargo of a ship holding hardware. That February they homed in on a likely target and, with the help of heavy equipment operators and some 60 other kindred spirits, began excavating the site. Proof positive of their prize came when they pulled up wooden crates stenciled “BERTRAND STORES.”

The salvors brought up nine wrought-iron vessels filled with mercury, each holding 76 pounds of the liquid metal. If the cargo had included 35,000 pounds of quicksilver, it would appear that salvage divers hired by the original insurers back in 1865 had removed most of it. Regardless, the true treasure of Bertrand turned out to be the trove of ordinary stores, clothing, foodstuffs and hardware that had lain encased in thick river mud for more than a century and emerged in a state of near pristine preservation. The salvors recovered such hard goods as knives, firearms and mining and agricultural tools, as well as fragile textiles and clothing, including shoes, coats, shirts and pants. Foodstuffs such as candy, ketchup, canned cherries, tomatoes, meat, peaches, pepper and spirits also survived the ravages of time. On display at the visitor center of the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge, near Missouri Valley, Iowa, the items recovered from Bertrand provide invaluable insight into everyday life in the late 1860s, while the story of the wreck itself is illustrative of the incredibly risky steamboat business in the emerging Western United States. WW