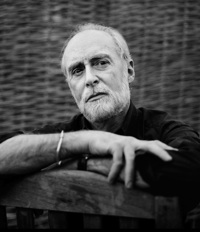

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Sydney Schanberg’s experience as a New York Times reporter in Cambodia as it fell to the Khmer Rouge in 1975, and that of his colleague Dith Pran, was immortalized in the 1984 film The Killing Fields. As a reporter and columnist after the war, Schanberg became the most prominent journalist to extensively investigate allegations that American POWs had been knowingly left in Laos in 1973 by a Nixon administration desperate to end the war. In a provocative, evidence-laden 2008 article, Schanberg described Senator John McCain’s role in the POW controversy and succinctly laid out the documentary record of what he believes has been a decades-long effort to conceal the facts.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Sydney Schanberg’s experience as a New York Times reporter in Cambodia as it fell to the Khmer Rouge in 1975, and that of his colleague Dith Pran, was immortalized in the 1984 film The Killing Fields. As a reporter and columnist after the war, Schanberg became the most prominent journalist to extensively investigate allegations that American POWs had been knowingly left in Laos in 1973 by a Nixon administration desperate to end the war. In a provocative, evidence-laden 2008 article, Schanberg described Senator John McCain’s role in the POW controversy and succinctly laid out the documentary record of what he believes has been a decades-long effort to conceal the facts.

The first-ever compilation of his war reporting, and the 2008 article, are presented in his new book, Beyond the Killing Fields: War Writings, published last fall. Schanberg spoke recently to Vietnam magazine and in this expanded version of the interview appearing in the February 2011 issue, Schanberg talks about Cambodia, Nixon’s decisions that sealed the fate of hundreds of POWs, his career and the state of journalism.

You didn’t set out to become a journalist?

No, journalism was kind of an accident for me. My father owned a neighborhood grocery store so we lived very modestly, but I got a scholarship to Harvard and I got good grades, When I graduated I really didn’t know what I wanted to do, so I decided to apply to law school and got into Harvard Law. Three months later I knew it was wrong place for me. My family was in mourning because I wasn’t going to the Supreme Court. I got a job in New York with a large company as a sort of an intern, an assistant to a vice president, and soon found that wasn’t going to do it either. I thought that if I just got away from the hullabaloo in a big city I might think it through and know what I wanted to do. So, as the draft was still in effect, I moved my name up. I did my basic training and they advanced me to Ft. Hood, and then our group was going to be shipped to Germany. I thought I really didn’t want to be doing maneuvers in the snow, so when I heard that there were openings on the division newspaper I applied. I had a very easy time but I learned a lot.

How did being in the military expand your worldview?

I learned about people who were career soldiers and who had fought in World War II, and I came to see, to understand some of what they went through, and understand what was meant when people talk about liberty, honor and courage and so forth. I also met some professional reporters covering the Cold War, and I just thought to myself, this is something that I’d love to do.

So after the service you launched your career?

When I got back, I started applying to newspapers and eventually I went to the New York Times and they gave me sort of like an SAT test. I must have passed because I got to be an office boy. That’s where it began, and I spent 26 years at the Times.

Your first venture into the Vietnam War actually took you to Cambodia?

In the Nixon incursion in 1970, I went to Cambodia for about five months. It was terribly important for me because I didn’t stay in Saigon, I went right to where it was happening up in the Northern provinces. And that was what spread the war all over Cambodia, which had been trying to stay neutral. Then we pulled our troops out after a short period, but what it did was push the Vietnamese deep into their country.

When did you get back to covering the war?

I was posted in India, and I went back around September or October to New Delhi, where I was a bureau chief. And then there was a war in India. When my stint in India wound down, they sent me to be Southeast Asia correspondent, covering all the countries except those engaged in the Vietnam War—the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and so forth. I did that, but I was still thinking about Cambodia, which was being covered by only a handful of people and getting really no attention. So I started going there. My editor wanted more reporting from Indonesia and Malaysia, but my heart wasn’t in it. I mean I did the best I could in the sense that there were interesting stories going on but none as dramatic or important to me as a little country being overrun by a war and nobody in the world giving a good hoot. So I just kept going back to Cambodia, and eventually they recognized that this was OK and that we could let Indonesia and the Philippines have a rest.

What happened to you in the spring of 1975 as the Khmer Rouge closed in?

When the Americans evacuated, I went to the U.S. Embassy and I got their permission to take out the family of my sidekick, Dith Pran. So his family was taken to the United States, and Pran and I stayed behind. We could not imagine ourselves sitting in Bangkok to cover the end of the war, which is what the rest of the press did. But the bad news was Pran was no longer protected from the onslaught coming. It was a very important piece in my life and it has remained very important.

Your book, The Life and Death of Dith Pran, and the movie Killing Fields won great praise, but you were criticized for not seeing the insanity that would come.

In the first hours of the Khmer Rouge entering Phnom Penh, there was celebration, everyone running around and waving flags. It looked like it was going to be peaceful. But soon we began to hear disturbing news from other parts of the city that they were telling people to get out of their houses and go into the countryside for the agrarian revolution. And they were firing guns in the air so that people would move, and I think a few people were killed inside the city because they weren’t moving fast enough or whatever, but there was no bloodbath. But you could tell that they couldn’t be reasoned with. Now, there were people in the American embassy in Cambodia saying “There’s going be a bloodbath,” but they had been bullshitting us for years about what was going on in the war. By then, we were surrounded by the Khmer Rouge, so you couldn’t go very far outside Phnom Penh. We were with 2 million people who were trying to be positive and so on. I admit I was so weary of the war and the killing that I think wishful thinking guided me.

I won’t look for excuses. When I wrote the 10,000-word piece in the Times about Pran and Cambodia, I said very high in the main story that I was wrong, and that we had been guilty of wishful thinking. But the truth of the matter is that in the history of war, at least American wars, our military and political leaders would often say, “We can’t leave because if we leave they’ll be a bloodbath.” They said it about Vietnam. They said it about a lot of wars prior. And while there was harshness in Vietnam, at rehabilitation camps and all that kind of thing, there was no bloodbath. But in Cambodia, it was true. We didn’t know how crazy the Khmer Rouge people were. But the truth is that when I look back on it, yes, we were all wrong, but the war never had any meaning. It didn’t have to happen. Cambodia didn’t have to be engulfed in war. I’ve said many times we were guilty of wishful thinking, but when I think about it and try to balance it, there was nothing we would have written that would have stopped it. America had decided to get out, so there was nothing that we could have said at the end that would have prompted the United States to go running in with a division of soldiers. So the reality of it was that this was going to happen, no matter what we had said.

How did that affect your journalism?

I sure think it was a mistake in judgment. What happens when you make a mistake like that is you know that you’re not ever going to do it again. I learned to never make predictions. Never try to describe what a country, or place or a situation is going to look like in the future. Just tell what you know.

How did you keep from becoming a victim of the Khmer Rouge yourself?

Pran and I and others were captured and taken to the banks of the Mekong River. We figured the Khmer Rouge were going to do what they’d done before in the war, that is, kill their captives and roll them into the river. It’s a long story, recounted in my book and the movie, but Pran talked them out of it. I was set free, but others on the riverbank were just waiting for their turn to get killed.

The POWs Left Behind

When the peace accords were signed in 1973, did you have any reason to believe that prisoners were left behind?

I had doubts, but hadn’t done the reporting. The Times did have a big story saying the State Department and other agencies were in shock, because even though they didn’t have proof that the North Vietnamese themselves had prisoners, they knew about POWs in Laos, and had names and numbers. The U.S. Embassy knew there were men in Laos. There was a story about Admiral Thomas Moorer halting the POW repatriation for a day because he was challenging the official list of prisoners, which had only nine listed from Laos. What nobody found out until eyewitness testimony years later was how Moorer pounded on Defense Secretary James Schlesinger’s desk, yelling, “The bastards have still got our men!”

Did you begin to believe early on, after you returned to the States, that we had left POWs behind?

I did, but it wasn’t by any ingenuity of mine. When I came back to New York, I was made city editor at the Times. That’s a very big job and you don’t cover foreign affairs from there. But people I had met in Southeast Asia who felt they could trust me came to me with maps and documents and stuff they collected. I didn’t have a real grip on the POW story but I knew it needed to be explored. So I took the information to the foreign desk and national desk. But I couldn’t get anyone to follow up at the time. But, I put it in my back pocket and years later, when I became a columnist covering New York, I did write some on Cambodia and POWs, but in a very general way, about reports that some prisoners were left behind.

In January 1973, did President Nixon, knowing he’s leaving POWs behind, make decisions he could never reverse?

I think so. It’s like, in life, if you tell a whopper of a lie, as each day passes, it becomes harder to confess. When they made the decisions to get the peace agreement signed, they could never turn back. It’s early 1973, Nixon’s just been reelected and Watergate is beginning to boil. We’ve bombed North Vietnam to bring them to the negotiating table in Paris, and now Nixon is trying to get the peace treaty signed. The North Vietnamese have the upper hand, however, because they know how bad we want to get out of the war. So, perhaps the pressures influenced Nixon into thinking, I’ve got so much on my back, I have just got to get out of this war now.

The peace treaty is signed on January 23, and then the North Vietnamese show us the list of prisoners to be released. This is when Admiral Moorer explodes. Nobody from the list of more than 300 names of prisoners who we are certain are alive are on the list of prisoners supplied by North Vietnam. No one from Laos is on the list. Nixon responds, saying that this was inconceivable. He even sent a message on February 2, 1973, to North Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, saying so.

So, what do you think was motivating Nixon to go along?

It is very peculiar. Was he worried about being accused of breaking international law by being in Laos? Why be worried about that when we are talking about 300 prisoners? Did he think the rest of the world was going to do something or charge him with war crimes? Whatever it was, it was never going to happen. Maybe he thought they could get the POWs back after some time passed. They were desperate in a way, they wanted to get the war over. With the Watergate scandal breaking, Nixon had other reasons to be desperate. I don’t think it was evil intent driving the POW coverup, but weakness. Then, how could either side admit to the lie later on?

You write about a Rand Corporation study for the Pentagon that actually predicts what will happen.

The Pentagon asked Rand to do study what the North Vietnamese might be planning to do after a treaty was signed. In the report they take up the issue of prisoners, and at the very end they predict they will do as they did when they defeated the French and hold prisoners to get the reparations they want. The French paid to get all of their prisoners out. They didn’t announce it, but they paid it covertly and their men came home.

What could Nixon have done, at that point, to get the American POWs out?

He could have paid the ransom, and we wouldn’t have lost anything. That is the one thing he could have done. I don’t think anyone would have howled too much about it because you are getting the people out.

Were you optimistic when the Senate Select Committee on POWs/MIAs was convened in 1991?

When the committee was formed and I saw that Sen. John Kerry was the chairman, I thought, well, he’s a smart guy, maybe he’ll bust this thing open. But the opposite was true. I was a columnist at Newsday and had very good sources because there were many people in the government who were angry. I wrote dozens of columns in the year and a half the committee was working. During this time I also went to North Vietnam with a POW family and wrote a four-part series.

Do some of the newly released Nixon Oval Office tapes shed light on the decisions?

The Pentagon is tasked to push Vietnam on this issue, but they get no response. While most of the Nixon tapes from this period have been released, when you go to look, many are heavily redacted. Even so, you can still tell when they are talking about the prisoners in Laos. In one conversation, Nixon says something like, “Maybe we could bomb southern Laos so they would loosen their grip.”

Is more information coming to light?

There is no stoppage in the flow of documents that people send me. I don’t always know where the documents come from or how they got them. Sometimes they will have already been declassified. But even though declassified, they can be very hard to find as they may be filed in places you would never know to look. I still get the stuff, your eyes would pop out if you saw it. A batch came in the other day about a sighting in Laos that happened six years ago. It is very clear and direct, saying that some Laotian citizens came to the U.S. Embassy in 2004 to report sightings and that they were arrested.

Why have so few of the Vietnam-era journalists worked the POW story?

Most didn’t go to Laos very often, they were side trips from Saigon. In any case, if you’re covering the war, you don’t know anything about captured men because it’s not brought up. Some were captured in South Vietnam, but most were captured elsewhere and journalists weren’t around. It just wasn’t an issue for those based in Saigon.

Are there other reasons?

Well, I had a friend, a journalist who was there, and we don’t talk to anymore. He’s an ideological liberal and the war was all bad for him. We talked about the POWs and you could tell he wasn’t a believer. And so I asked him to read my pieces, and he would never read any of the articles I wrote. So finally I said, “Well tell me how you can be so sure that it didn’t happen if you haven’t examined the evidence?” He said, “Well look, all I know is that if it had happened we would have known about it by now.” And I said how would we have known about it if there were only reporters running around like you? I decided that the fact was that he wasn’t committed to journalism, he was committed to ideology and to being angry at the war.

You are critical of reporters today for having cozy relationships with officials.

I’m not here to make anybody look good or bad, I just have to tell what I find out. In any case, many reporters are really in the pockets of people, especially in Washington. They cover the Pentagon, they go on trips with the defense secretary and he’s a pretty straightforward guy, but his anthem isn’t theirs and it shouldn’t be. They are afraid of losing access. It’s not good. We need the tension, not because we have to demonize anybody, but because, at least in my mind, we really owe it to the public to tell people what war’s all about.

Doesn’t the public have an obligation to know and isn’t the media beholden to informing them, especially about war we are paying for?

What you’re paying for is not just in treasure but in the men we lose, men and women now. Is every war necessary or unnecessary? There has to be a reason for war and an explanation why we can’t do it some other way. Presidents always say it’s a last resort but we’ve seen that’s not true. I am as much disappointed in—even more so in a way—in my profession than I am in the broken-down government we have now.

Like the POW issue, the original motivations for our current wars are not challenged but rather seem to be just accepted by the media?

Well we really didn’t have a handle completely on everything, because we didn’t have all the information. But you know in the press, Knight-Ridder was gung-ho on exposing the falsehoods and the evidence. They were purchased by McClatchy newspapers, and they are still doing it, still holding the government accountable and it’s very good to watch. However the rest of the press, they won’t touch it. And what’s their explanation? I asked an editor on a major paper and his explanation is sort of something like “Well you know, I don’t see their stuff.” And I would say, “What are you talking about?” And he said, “Well they have no large paper in a major city.” So in other words, they’re not in the capital, they’re not in New York, Chicago or Los Angeles. And I said, “And that is why you’re not looking at their stuff everyday to decide whether you should be doing the same kind of thing?” It’s sad.

Do we have a flawed model?

The press corps that sits in the capital is often the least aggressive because of all the access stuff. That’s not new. You know, you need to feel independent. And a lot of these people don’t.

Even with your bona fides, you’ve fallen out of the mainstream.

I think that what I have become, at least in mainstream journalism, is someone who has challenged many of the mainstream media’s, let’s say, rules of the game. And so, I guess I’ve pissed off a lot of people. I don’t take that as a badge of honor, but I think you really do have to piss off a lot of people and you will automatically piss them off if you write about what they really do. Because usually, you know, it’s the same old story.

Most of the time, I enjoy being who I am. And sometimes, you know, getting rebuffed makes me sort of howl at the moon, you know. But I only do it for a few minutes and I come back in and get back to work.

So, after all these years, your efforts and those of others, how does the truth about our POWs ever come out?

I believe there are only two ways the story will come out. One would be if a POW is still alive and escaped and were given asylum by another government and were able to prove that they were not a deserter. That would really peel the lid off the thing. The other way is if somebody who was or is in our government stands up and says, this is what happened.

What do you say to your colleagues who just think this is a crazy conspiracy theory?

When someone says, “How can you believe this, it all sounds like a fairy tale,” I say just look at the evidence. If you can refute it, go ahead, but I know you can’t.

Hasn’t there been a conflation of this issue with the far right wing that has harmed credibility?

I think that’s quite true that people often assume this is a right wing issue and we shouldn’t listen to them. I know a lot of people d exaggerate and hurt the cause, but they have been lied to for so long. People say to me, “You’re a liberal, why are you writing about this?” I say, “Whatever I am, I’m not a liar.” This is a national story.

Is there any legitimate reason that information about the POWs should remain classified?

It’s been 38 years since that first terrible decision was made, and I think you have to be brainwashed to believe there is any national security issue still involved. I tell people: If you don’t want to reveal names or methods of intelligence gathering, or things that shouldn’t be divulged, take it out. I don’t need to know the CIA’s methodology; I don’t need sources’ names. I really do believe that if information like this is allowed to come out, we become more of a democracy. Democracies are inefficient. Dictatorships are the easiest way to go. So it would be difficult for a while and you have to win back the people’s faith. People will holler and yell and scream, but it needs to be brought out into the light. I think it can be done.

After all these years working this story, what are you hoping for now?

What we really deserve at the least, especially the families, is to get the documents out so we can see them and clear the air. I’m not looking for a way to excuse anything or turn everyone involved into a demon. We don’t have to have a war crimes trial. The truth is enough. Then we can go on from there.

It is still one hell of a story.