Matthew Hulbert started with Jesse James and ended up exploring how the Civil War helped win the West. His 2016 The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West showcases how guerrilla warfare in Missouri was remembered, mis-remembered, or forgotten. “Most guerrilla conflicts happen out in the woods or on somebody’s front porch,” Hulbert says. “That’s much harder to deal with than, ‘Hey we’ll buy these acres of a battlefield and everyone can come visit and learn what happened here’.”

CWT: How did you get interested in guerrillas and Civil War memory?

MH: A fascination with Frank and Jesse James, which led to John Newman Edwards, who was sort of the first architect of the way we remember guerrillas from the borderlands. Following that thread led to a broad, uncharted topic.

CWT: What happened to Jesse James?

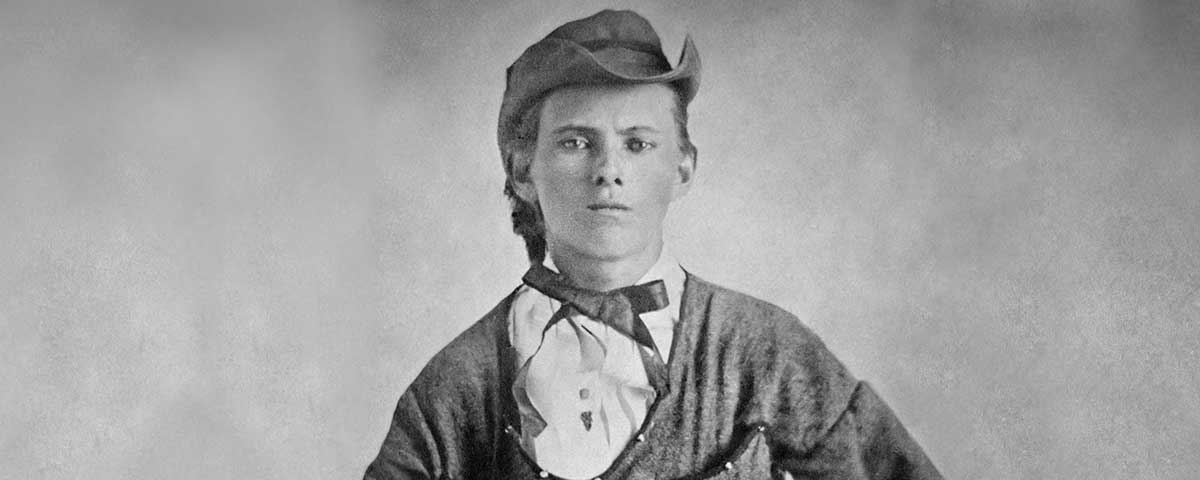

MH: Jesse James joined up in 1863 with William Quantrill’s guerrillas. His brother Frank is already a guerrilla. Frank joins the regular forces early in the war and is paroled and comes home and joins up as a guerrilla. Jesse James witnesses his stepfather Dr. Reuben Samuel being tortured by essentially Union guerrilla hunters who are looking for Frank because they know he is riding with Quantrill. After that Jesse joins as a teenager. He’s in the war for 2½-3 years, and he’s wounded a couple of times. When it comes time to surrender, James falls in with men who were not going to do that—they are staying on the highway, staying in the bush. They gradually consolidate into a crime ring.

CWT: Why are the James brothers famous?

MH: When the war in Missouri ends, it’s very apparent to everyone who waged it and experienced it in the borderlands that this does not look like the conflict that has been fought in the Eastern Theater. The Lawrence [Kan.] Massacre, the massacre at Centralia [Mo.], even the daily household violence where a few guerrillas burn and pillage a house, this doesn’t look like what we see at Gettysburg, Manassas, or Petersburg. John Newman Edwards is really the first propagandist who sees an opportunity to say, “Hey, we have a different story to tell…We might as well exploit that for political purposes rather than hide from it and sort of fabricate this past.” He does it in such a way that plays on their “irregularness,” or their otherness. The James go on to become arguably the most famous criminals in American history. They’re right up there with Bonnie and Clyde.

CWT: Edwards promotes a Missouri Lost Cause.

MH: He starts out as sort of the publicist for the James Gang, and he sees how easy it is to morph them into Confederate heroes: They’re not stealing because they want the money; they’re not stealing because they’re greedy or lazy; they are doing this to get back at the Union. They are pro-Confederate terrorists. He sees how well that works, and he says I could do this with William Quantrill and all these other really well known guerrillas and I can blow this up into something really much bigger. And that’s exactly what he does.

CWT: Were people eager to hear this?

MH: People are eager to hear this. Missouri is split much in the way that Kentucky was—down the middle, about half Confederate sympathizing and half Union sympathizing. So when Missouri fails to leave the Union, all of those pro-Confederates are left in the lurch. They can leave the state or they can fight as guerrillas in the state, and people do end up doing both, but after the war, they are starved for a connection to the Confederacy proper, and Edwards gives them that connection and he does it in a way that doesn’t sell short their experiences. If you experienced the war as a guerrilla conflict, you know you didn’t experience it the same way as someone whose main experience was at Gettysburg or at Manassas. Edwards is telling you that’s fine. We can still be Southerners, we can still be Democrats, can still have a fighting past with the Confederacy.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]Very few people are are familiar with Jesse James the Confederate guerrilla[/quote]

CWT: How does this shape perception overall of the West?

MH: There’s a transition. It starts with what I call outlaw histories, which began competing with the John Newman Edwards narrative in the 1870s. These are very early histories of the war, before history is a professionalized [and carefully sourced]. Standards are not high. These guys start the process of pushing guerrillas out of the story or pushing them west. And those outlaw histories become the source or bedrock for dime novels, predecessors to comic books and cinemas. In illustrated dime novels, and in fictional stories that people assume are based on fact, the James brothers are portrayed as cowboys. They’re in Texas, they’re in Mexico, they’re in Wyoming, they’re having gunfights at high noon, they’re fighting cattle barons. They’re doing all these things we expect of Western cowboys not Civil War soldiers. Dime novels gradually bleed over into cinema, and on film everyone knows Jesse James as the highwayman, the bank robber, the gunslinger, but very few people are familiar with him as a Confederate guerrilla. He is by far the best known figure and becomes the face of the movement to Westernize.

CWT: What do you mean Westernize?

MH: In the book, I am most interested in exploring how the West as an idea gets used to cleanse the war and its mainstream narrative of all those ugly things, of the Lawrence Massacre, of Centralia. There is a counter to Edwards: Edwards says it’s okay to have experienced the war this way, we should play it up. But we have these architects of memory in the East who say, that makes the war ugly and we’re turning the conflict into something honorable and chivalrous. We’re holding up guys like Lee and Grant who are heroes. We really don’t want William Quantrill and Bill Anderson running around scalping people and cutting off fingers and burning down houses with women and children in them, so we’re going to make them like cowboys. If we send them out West, that’s exactly how we expect people to behave on the frontier. It’s not civilized yet, so guerrillas get repurposed. Rather than stock and trade Civil War soldiers, they’re the people who bring civilization in the rough and tumble way to the West because when you’re going to burn down and kill and scalp Indians or other nonwhite people that’s fine to audiences in the 1870s and 1880s; you’ re just not supposed to be doing it to other white people.

CWT: What surprised you most?

MH: I was surprised to find that if you’re in Missouri, you’re supposed to hold a grudge against Kansas, and if you’re in Kansas you’re supposed to hold a grudge against Missouri. A lot of people seemed to know that, but I was a little disappointed to find out that not very many people knew why. The grudge [dating from the states’ differing stances on slavery] has survived but not necessarily the reasoning behind it. Public history in the western borderlands, especially Missouri and Kansas, is just so difficult when you don’t fight on battlefields, when you’re not part of organized armies who have institutions behind them and can commemorate them after the war.

CWT: You say the war was about more than emancipation.

MH: There are scholars looking at this as a continental struggle: On one side we have a war for emancipation going on in the East, but the stakes of that conflict are so much higher when we realize that we’re not just deciding the slavery question in the eastern half of the United States, we’re also deciding who is going to control the rest of the country. What will it look like? Will it be Confederate? Will it be controlled by the Union? Someone is going to establish an empire out of this, and that is what we’re really fighting to control. Missouri is sort of the portal where those two halves get plugged in.

Interview conducted by Senior Editor Sarah Richardson.