Angela Zombek, assistant professor of history at University of North Carolina-Wilmington, grew interested in military prisons during a visit to Camp Chase, a Union facility in Ohio. Over time, her studies turned to the 19th-century penitentiary movement, where incarcerated criminals were subjected to solitary confinement and conditions designed to evoke penitence and rehabilitation. How that tradition influenced Union and Confederate military prisons during the crisis of the Civil War is the subject of her book Penitentiaries, Punishment, and Military Prisons.

CWT: Tell me about the pre-Civil War state of prisons.

AZ: Long term imprisonment developed at the turn of the 19th century when the middle class thought having a public pillory wasn’t a good idea anymore because the danger in that, or in having a public execution, is arousing sympathy for criminals. Penitentiaries and a long-term system of punishment develops. Corporal punishment and executions moved behind penitentiary walls, away from the public.

CWT: Yet sometimes the public could participate?

AZ: Penitentiary executions were advertised as spectacles, if you were basically middle class, you could buy a ticket to see that. They also decided that they could charge admission so people could see the operation and see how inmates interacted with the guards. Those things came up later in military prisons. Governor David Tod of Ohio, for example, allowed curious people to tour Camp Chase for 20 cents.

CWT: How many were imprisoned?

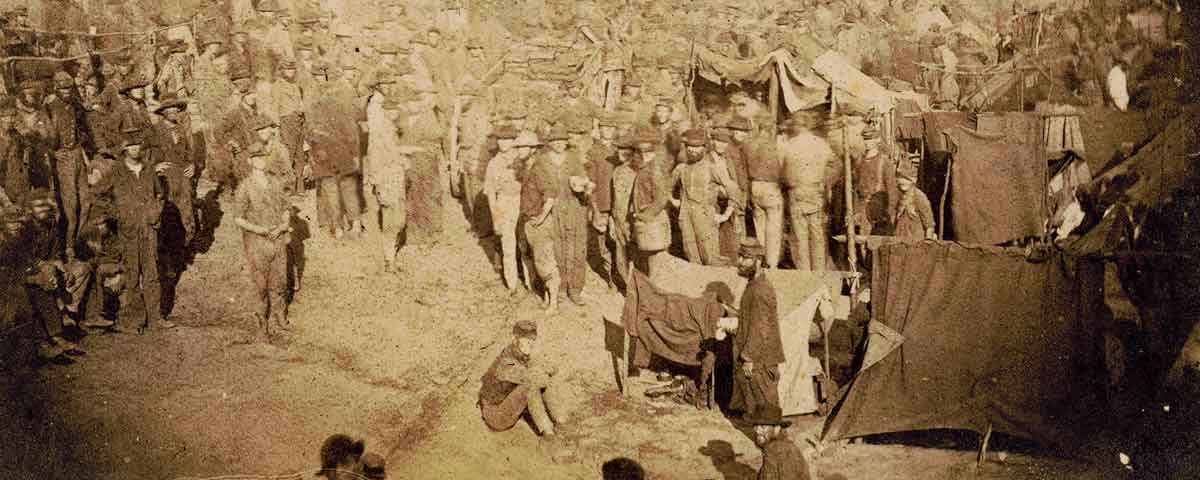

AZ: People have estimated that about 490,000 people total were incarcerated during the war. That number is just limited to military prisons that got established by the Union and the Confederate governments. That number wouldn’t necessarily include the people who weren’t POWs or were suspected of treason.

CWT: Did prisons in the North and South face different challenges?

AZ: I think they really did. That is apparent at Andersonville, Ga., which is established late in the war. There aren’t clear lines of authority. That’s not just related to Andersonville. When the prison at Salisbury, N.C., gets established, the first commandant is appointed by the state governor and he doesn’t know if he has the authority to do anything. That was the case at both Andersonville and Salisbury.The commandants had very little authority over prison conditions. Take Henry Wirz, the commander at Andersonville. He became a scapegoat at the end of the war when he was executed. But the things he could actually do to administer the camp were few and far between. For example, he had no power over the commissary. He had the rank of captain. There were literally some commanders of the guard regiments who outranked him.

CWT: Was there a general understanding about how POWs should be treated? You mention political philosopher Francis Lieber’s 1863 General Orders No. 100 on the conduct of war.

AZ: Both prisoners and officials are looking back on penitentiary imprisonment in the earlier part of the 19th century for guideposts. That’s what Lieber did because he was held as a political prisoner in Europe [in his native Prussia in the 1820s]. He was well aware of the standards that wardens in the state should use to treat incarcerated criminals, and those standards are basically transferred in terms of food, clothing, and cleanliness, over to military prisoners.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]Ohio Governor David Tod allowed people to tour Camp Chase for 20 cents[/quote]

CWT: Prisoners were also worked as laborers in some cases, although Union soldiers often refused to be clerks for the Confederacy.

AZ: Those were basically efforts by Confederate officials to make up for lack of manpower. If they wanted a prisoner to be a clerk, for example, he was made to swear allegiance to the Confederacy. If Union prisoners had to go out to collect wood, that’s one thing because it’s for survival, but if they are going to work in a position sanctioned by the government, that is basically shooting arrows at their own cause. There was a lot of resentment toward prisoners who decided to take those positions in the Confederacy.

CWT: What other kinds of work did prisoners do?

AZ: Lieber wrote in the General Orders No. 100 that prisoners may be made to work for their captors. So officials on both sides used prison labor to make improvements to the camp, to build barracks or forms of shelter, to dig ditches, to clean up waste in various forms.

CWT: You also mention Confederates who brought slaves to prison.

AZ: That was an issue that caused controversy in Columbus, Ohio, when Confederate officers held in Camp Chase brought their slaves with them. Once the civilians in Columbus got wind of that, they were absolutely irate, had no tolerance for it, started writing editorials to local newspapers drawing attention to it and contacting the Lincoln administration to stop that practice, which they eventually did.

CWT: What happens at war’s end?

AZ: Officials try to send prisoners home as quickly as they could. The Union did it by rank and were much more likely to send home privates than officers. They wanted to keep closer tabs on the people who actually led the companies, maybe even led the armies. That process is slow. The prisons in the South, especially in Richmond, were taken over by the U.S. government and used to help keep order in the city. That’s basically the case with Castle Thunder.

CWT: Is there a takeaway for the war’s impact on our current prison system?

AZ: Number one, it got the federal government involved. Before the Civil War, there was only one federal prison, the D.C. penitentiary. It was shut down in September 1862. It got reopened toward the end of the war due to the need for space. But in the latter part of the 19th century we start to see the opening of federal prisons. Number two, the Civil War generates another reform wave because of Congress’ investigation in 1867 of Southern military prisons and because of what had gone on during the war. The National Prison Association forms in 1870, and is drawn again to the same issues, such as the conditions, the crowding, the food, the treatment. But again the actual reform of the institutions falls by the wayside.

CWT: Anything else you’d like to add?

AZ: The correspondence that prisoners in both military prisons and penitentiaries had with people at home was so moving. In correspondence from family members on both sides, I saw so profoundly that relatives of convicts and relatives of POWs say you have to trust in God and put faith in him. ✯

Interview conducted by Senior Editor Sarah Richardson