Parties have used lame-duck judicial appointments to advance their agendas since Marbury and Madison were pups

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the 87-year-old Supreme Court justice, died on September 18, 2020. Eight days later President Donald J. Trump announced that he would be nominating Appellate Court Judge Amy Coney Barrett, a 48-year-old conservative Republican, to replace the liberal Ginsburg, a Democrat. In a two-week span—October 12 through 26—Barrett was whisked through the Republican-controlled Senate on party-line votes whose speed and timing stoked Democratic wrath. Vox populi, the Democrats argued, was due to speak on November 3, when the nation indeed did reject Trump’s bid for re-election. By quick-marching Barrett onto the High Court bench beforehand the incipient lame duck and his Senate partisans had pre-empted the people’s choice.

The Founders knew all about judicial power plays, which they pulled not just in the fourth quarter but after the whistle blew, in the interval between defeat and leaving town.

In November 1800, as his term was ending, President John Adams asked Congress to expand the federal judiciary. There were sound good-government reasons for doing so. Federal circuit court judges, and the Supreme Court justices who then heard cases alongside them, had to cover enormous swaths of territory—a mere three circuits served the entire country. Riding circuit, often a literal activity, involved traveling hundreds of miles on execrable roads and untamed waterways. Mishaps ensued. Justice James Iredell, assigned to the Southern Circuit, was thrown out of his carriage by a runaway horse; Justice Samuel Chase of the Middle Circuit fell into the Susquehanna River when the ice on which he was crossing gave way. Increasing the number of magistrates and regrouping them into smaller circuits would reduce wear and tear on judicial bodies and make justice more accessible.

However, judicial expansion was also a jobs program for Adams’s Federalist Party, which badly needed employment.

The election of 1800 had been a debacle: Adams lost the White House to Thomas Jefferson, while Federalists took a beating in both houses of Congress. Gouverneur Morris, one of the Federalist survivors, explained in a letter to a friend what his party was about to do. Foundering as the Federalists were in “a heavy gale of adverse wind,” Morris wrote, “can they be blamed for casting many anchors to hold their ship through the storm?”

The lag between federal elections and winners taking office was twice as long as now, from November until early March. The Federalists used every day of that interval.

A crucial Supreme Court vacancy needed filling. Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, beset by kidney stones and gout, wrote Adams in December that he was stepping down. To replace him, Adams turned to diplomat, wartime spymaster, and Federalist Papers author John Jay. Easy call—Jay had been chief justice 1789-95. The Senate quickly confirmed him—and Jay as quickly responded that he had been there and done that and the hell with it. The High Court, he wrote Adams, lacked “the energy, weight and dignity which are essential to it.” Jay would stay home.

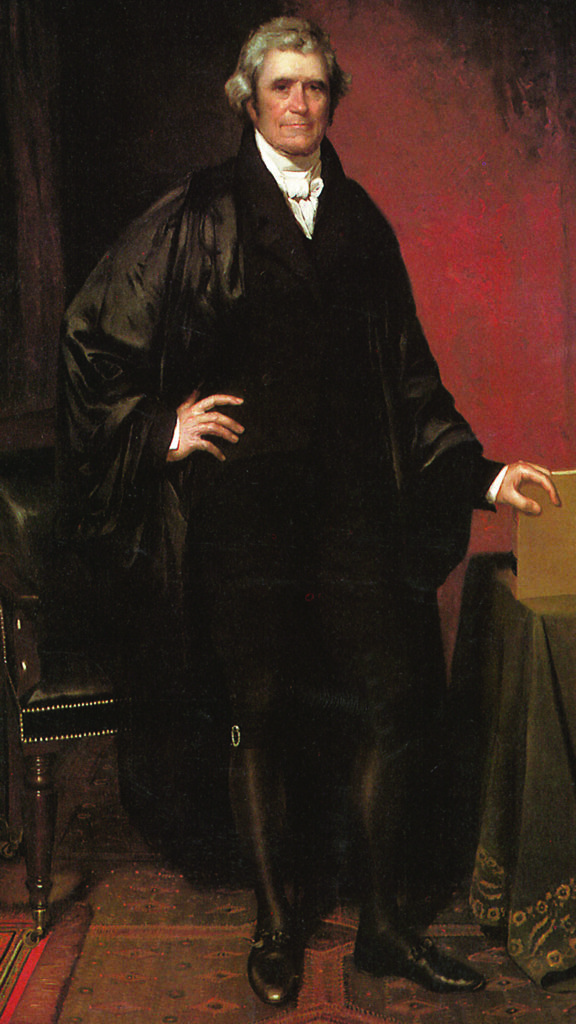

The man who handed Jay’s rejection letter to Adams was his secretary of state, John Marshall. “Who shall I nominate now?” Adams asked. Marshall had no suggestions. After a minute’s thought, Adams decided, “I believe I must nominate you.” Marshall’s only judicial experience had been serving as a judge advocate in the Continental Army at Valley Forge; his only legal training had been home-schooling, plus a semester of introductory law at William and Mary. He had, however, been practicing law successfully in Richmond, and he was right there on the spot, meaning no time would be lost to exchanging correspondence. The Senate confirmed Marshall on January 27, 1801.

In February, Congress addressed Adams’s November suggestion by passing a Judiciary Act that split each federal circuit in two and created 16 circuit court judgeships to administer them. The District of Columbia Organic Act added three more circuit judges sitting in the nation’s newly established capital.

This episode of court-packing on a grand scale bowed to nepotism as well as partisanship—one new DC judge was a nephew of President Adams, another appointee there was James Marshall, younger brother of the chief justice.

Adams finally named 42 justices of the peace for the District of Columbia, responsible for hearing minor cases. In a burst of fair-mindedness, not all Adams’s choices were Federalists—only three-quarters of them, including a Georgetown banker, William Marbury.

In the space of three months, Adams and Congress had nominated and confirmed two chief justices of the Supreme Court, created and filled 19 circuit court slots, and appointed a slew of capital district dogberries. Not bad for a flock of lame ducks.

The victorious Jeffersonians answered push with enthusiastic shove. Most important was ridding the system of those new circuit court judges. The Constitution, in Article III Section 1, says federal judges serve “during good Behaviour”—i.e., for life, unless they commit some offense. Instead of removing the new judges from their jobs, the Jeffersonians took the jobs from the judges. A new Judiciary Act, passed on party-line votes in March 1802, kept the smaller circuits, but pared the number of magistrates to its pre-1801 total.

And what if Congress were to decide that a Federalist judge had behaved badly? The Constitution empowers the legislature to impeach and remove jurists from office; see Article I Sections 2 and 3. Congress began by knocking off John Pickering, a Federalist judge of the New Hampshire district court—the level below circuit courts—in March 1804. That was an easy task—Pickering had lost his mind and taken to drink. The same month, the House took aim at bigger game, impeaching Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase.

The Jeffersonians indulged in modest court-packing of their own in 1807, adding a justice to the Supreme Court. Like the Federalists before them, they had a good government reason—beyond the Appalachian Mountains lay three new states, increasing the caseload. As the Federalists had, the Jeffersonians filled the newly created seat with a good party man, Kentuckian Thomas Todd.

The Jeffersonians’ most minor juridical chore concerned commissioning the District of Columbia’s justices of the peace.

In the Adams administration’s last remaining hectic hours, John Marshall, despite his new judicial eminence, still served as secretary of state. Somehow, Marshall failed to present William Marbury with his official commission. When the Jeffersonians found the certificate on a State Department desk, they refused to deliver it.

Not every one of these countermeasures worked. Chase survived his Senate trial in March 1805 when the House bungled his prosecution. Marbury sued unsuccessfully to obtain his commission, the Supreme Court ruling that the remedy he sought was technically unconstitutional. However, that opinion, a monster written by Marshall, was a long scold of the Jefferson administration for not giving Marbury his job in the first place.

Other retorts succeeded. The courts refused to overturn the Judiciary Act of 1802 when a litigant claimed it to be unconstitutional. Jefferson’s man on the expanded Supreme Court bench would serve for many years—as would justices Jefferson and his successors appointed when Federalists died or retired. To Jefferson’s dismay, the newbies all ended up siding with Marshall, which veers into the x-factor zone of personal and intellectual leadership.

The Constitution’s authors took that document seriously. They would not violate it—but they would wring from it every drop of political advantage they could. Elections allow the people to elevate and to rebuke. But losers serve—and may act—until the moment they leave office—when the winners begin the labor of demolishing predecessors’ handiwork.

This Déjà vu column appeared in the February 2021 issue of American History.