Fixated upon his country’s national identity, Miklós Horthy yearned for a way to reclaim its lost glory and lost territory.

IT IS NOVEMBER 20, 1940, and there is excitement in the air. Two months earlier, when the signing of the Tripartite Pact on September 27 brought the three-party “Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis” into being, German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop had announced that “any other State which wishes to accede to this bloc . . . will be sincerely and gratefully made welcome.”

Now, Hitler and Ribbentrop are ready to welcome additional members to their notorious club, and both Hungary and Romania are eagerly maneuvering for the coveted fourth slot. In Berlin, Döme Sztójay, Hungary’s ambassador, is on the phone with foreign minister István Csáky in Budapest. There is a breathless urgency in his voice—Ribbentrop is practically holding out a pen for Sztójay to sign the document, but he must act quickly. Romanian dictator Ion Antonescu will be personally arriving in Berlin within 48 hours.

Hungary’s regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy, wrote in his memoirs that “considerable efforts were made to make it appear that a signal honor was being paid us in allowing us to join Germany, Italy and Japan as a fourth partner, but a hint was also dropped that should we hesitate to accept it, Romania would be given this ‘place of honor.’”

As Ribbentrop waited, Horthy ordered Csáky to tell Sztójay to take the pen and sign. By the time Antonescu arrived in Berlin to join the Axis on November 23, Hungary had been the fourth power for three days.

For Hungary, being fourth carried with it both the prestige of being first to join the original three and the satisfaction of beating archrival Romania. Though Hungary and Romania were now both part of the Axis, their ethnic and territorial animosity was deep-seated, predating even having been on opposite sides in World War I. Much of this centered on Transylvania, a 40,000-square-mile mountainous region that had been Hungarian—albeit with an ethic Romanian minority—for the better part of a millennium, but which was granted to Romania by the victorious Allies after the First World War.

The three original signatories of the Tripartite Pact, because of their size and the weight of their armed forces, determined the strategic direction of the Axis and bore the brunt of the war against the Allies. But they were eager for additional material support, and the new fourth and fifth Axis powers, Hungary and Romania, were equally eager to contribute. For Horthy and Hungary, embracing the apparently invincible Hitler seemed like a brilliant maneuver as, with that stroke of the pen, Hungary was on the road to reclaiming lost territory and lost prestige. But, as Horthy discovered all too soon, there was a price to pay for making a deal with the devil.

WHO WAS Miklós Horthy, once a household name as the fourth Axis head of state but who has since slipped into obscurity?

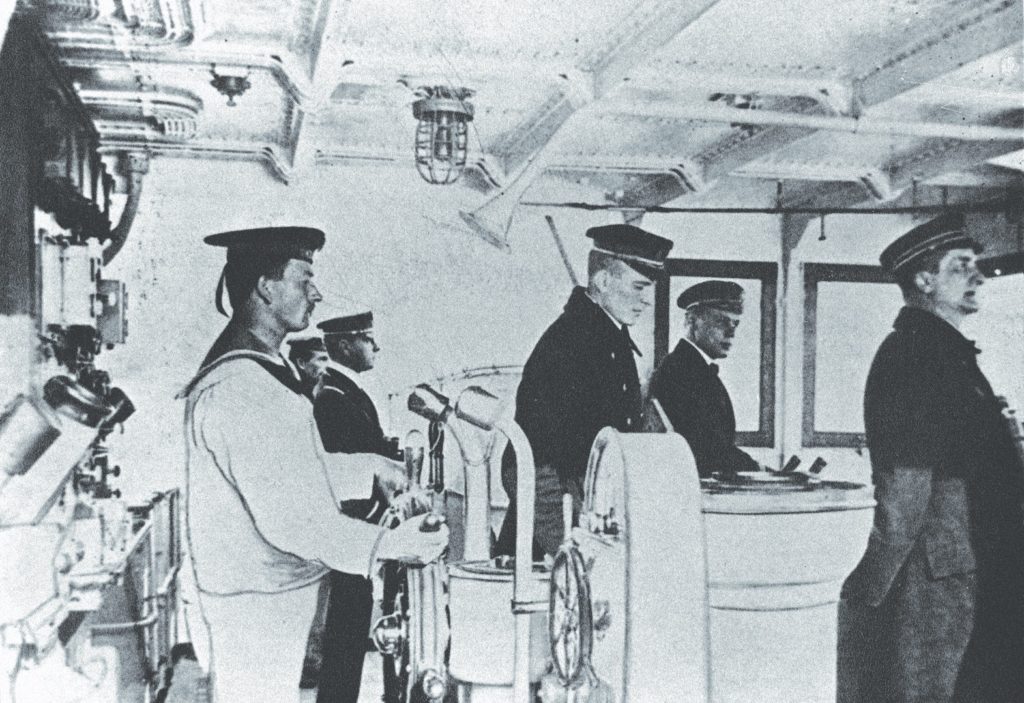

A nobleman from Kenderes, Austria-Hungary, Horthy was a man in the right place at the right time—repeatedly—whose luck consistently allowed him to bounce back from what seemed to be insurmountable calamities. In 1892, he was a young Austro-Hungarian naval officer on an extended cruise to the South Pacific. In Australia, Horthy’s party picked up Austrian geologist Baron Heinrich von Foullon-Norbeck, who was surveying various South Sea islands in search of minerals. On this trip he was headed to the Solomon Islands, then a German protectorate. He went ashore some 30 of these islands, including Guadalcanal, and Horthy was the officer who accompanied him. On Guadalcanal, they found traces of both gold and nickel.

Four years later, the baron returned to Guadalcanal, where he was murdered by locals who took exception to his attempt to climb Tatuve, a sacred mountain. By then, Horthy’s naval career had already taken off. He commanded a series of progressively more important naval vessels and eventually became the naval aide and favored hunting buddy of Austria-Hungary’s Emperor Franz Josef I.

When World War I began, Horthy was in command of the battleship SMS Habsburg. In May 1917, leading a force of three cruisers and other supporting vessels, he achieved a victory over the Allied navies in the Battle of the Strait of Otranto, the largest ship-on-ship surface action in the Mediterranean since the Napoleonic Wars. In February 1918, Horthy was promoted to rear admiral and named commander-in-chief of the Austro-Hungarian Imperial Fleet.

Half a year later, the war ended badly for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which shattered into fragments, some gobbled up by Italy and Romania and the rest reinvented as separate countries. Hungary was one of these. It became an independent entity for the first time in over a century, but it was just a shell of its former self. Before World War I, as part of the empire, Hungary had an area of 125,000 square miles; when the war ended, it was reduced to fewer than 36,000 square miles. A great deal of land was lost to newly created Czechoslovakia—but particularly irritating to Hungarians was the loss of Transylvania to Romania.

Internally, the Kingdom of Hungary descended into chaos and instability, with a revolving door of governments. Karl I, of the House of Habsburg, who had become the Emperor of Austria-Hungary when his great-uncle Franz Josef died in 1916, had also reigned as King Károly IV of Hungary. However, the Allies did not want the Habsburgs on the throne—the 1920 Treaty of Trianon abolished his first job and would not allow him to take the second. Karl/Károly renounced participation in Hungarian affairs but did not abdicate. Therefore, Hungary became a kingdom without a king, and the country fell into political turmoil. In March 1919, the Communists seized power, established the Hungarian Soviet Republic, and began what was called the Vörösterror (Red Terror), a period marked by chaos and political executions.

For Admiral Miklós Horthy, who largely avoided being caught up in the postwar turmoil, the war had ended not so badly. Under orders from his government—who now took their orders from the victorious Allies—he had surrendered all of the Austro-Hungarian navy’s ships and naval bases. He hung up his sword and retired to the family estate at Kenderes.

By 1920, however, having deposed the Soviet Republic and readopted its identity as the Kingdom of Hungary, the country yearned for a steadying hand and turned to war hero Horthy. He was called out of retirement, first to head a new national army to restore order and then to lead the kingdom. Since the Habsburg monarch could not rule, the situation called for a “regent,” or pro tempore ruler. Thus, as a kingdom without a king, landlocked Hungary embraced the admiral without a navy.

As regent, Horthy fixated upon Hungary’s national identity and yearned for a way to reclaim its lost glory and lost territory. Humiliated Hungary and its regent needed a powerful friend, ideally one who shared their disdain for Allied treaties. They found him in the person of Adolf Hitler.

WHEN HITLER CAME TO POWER in 1933 with territorial ambitions toward rebuilding and expanding the German Reich, Horthy hitched Hungary’s wagon to the star with the swastika emblazoned upon it.

In the near term, this seemed to have been astute political mastery. By the mid-1930s, Hitler was in his ascendancy—and, just as he was keen to undo perceived injustices done to Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, he promised Horthy that he could do the same for what Trianon had done to Hungary.

Horthy first met Hitler at Berchtesgaden in 1936, recalling in his memoirs that the Führer was “a delightful host” who “had shown nothing but goodwill toward Hungary” since coming to power. He met with Hitler on several later occasions and was also graciously received by Mussolini in Rome. In August 1938, Horthy and his wife, Magdolna, received an extravagant state welcome in Berlin and then traveled on to the Reich’s naval base at Kiel. Here, Magdolna, as the wife of the Austro-Hungarian fleet’s former commander-in-chief, was honored with christening the German cruiser Prinz Eugen. Her husband, given every naval honor imaginable, beamed. In his memoirs, Horthy claimed that he was already wary of Hitler—but photos from this visit show both men grinning ear to ear.

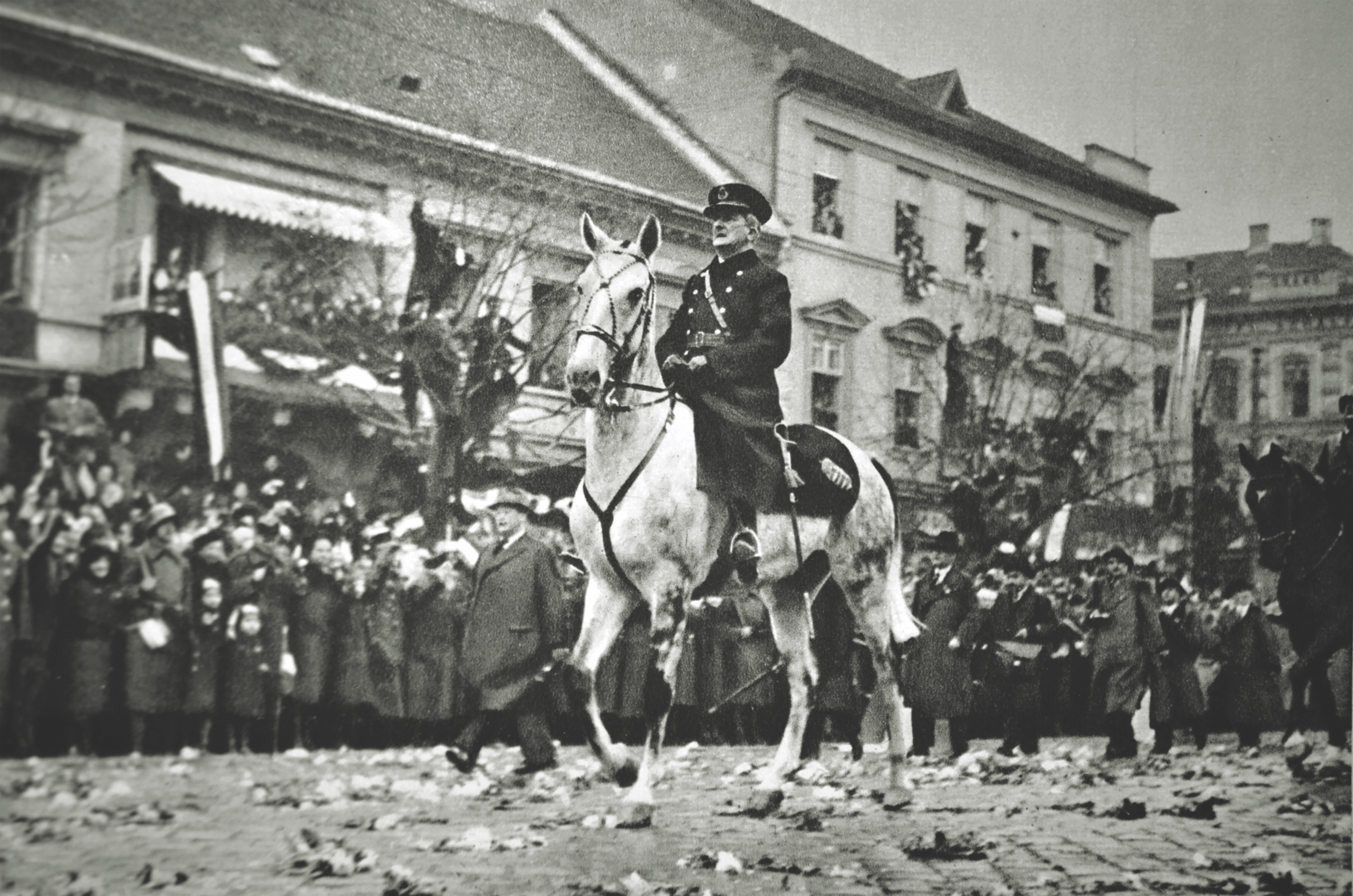

After the infamous Munich Conference of September 1938, Britain and France gave Hitler carte blanche to occupy the German-speaking Sudetenland areas of Czechoslovakia, which he did in October. A month later, Hitler and Mussolini twisted the Czech arm even further in the so-called “First Vienna Award,” giving Horthy the green light to start reincorporating Hungarian-speaking slices of Czechoslovakia into Hungary. Headlines in the New York Times of November 7, 1938, read, “Horthy Is in Tears in Reclaimed City: Hungarian Regent Has Triumph at Komarom—Crowds Shout for More Territory.” Hungary even issued a postage stamp picturing Horthy riding across the bridge into Komárom on a white horse.

Meanwhile, Romania had gained territory at the end of World War I from both the collapsed Russian Empire and from Hungary, but by the summer of 1940 it was between a rock and a hard place. The Soviet Union took back what had been taken from Russia, while Hitler and Mussolini pressured Romania’s corrupt King Carol to return Transylvania to Hungary. In the wake of this, Carol abdicated, handed his dictatorial powers to pro-Hitler General Ion Antonescu, and left his teenage son Michael as a figurehead. In the chess game of eastern European power politics, Antonescu reluctantly accepted Horthy’s reoccupation of Transylvania as the price of having Hitler on his side to counterbalance the Soviets on his eastern border.

Again astride his white horse, Horthy personally and colorfully led the Hungarian First Army into Transylvania on September 6, 1940, two weeks before the signing of the Tripartite Pact. About 1.3 million ethnic Hungarians and roughly the same number of ethnic Romanians became Hungarian citizens. The New York Times reported that 30,000 Hungarians cheered Horthy’s dramatic arrival. For Miklós Horthy, it was the best of times, the apogee of his reign as regent.

In April 1941, when Hitler’s legions marched through Hungary and into Yugoslavia, the Hungarian Third Army marched with them, adding more than 8,000 square miles to Horthy’s Hungary. By the spring of 1941, Hungary had nearly tripled in size since 1938 to more than 90,000 square miles.

Two months later, on June 22, when Hitler launched his Operation Barbarossa invasion of the Soviet Union, he expected Horthy to step up to his role as an Axis leader. Horthy initially hesitated. However, on June 26, an air raid struck the Hungarian city of Kassa. His German friends presented Horthy with compelling evidence that the Soviets were responsible, and Hungary joined in Barbarossa. Through the years, though, many—including Horthy in his memoirs—would insist that the Kassa raid had been staged by the Germans.

In any case, both Horthy and Antonescu supplied forces to serve under the command of the Wehrmacht’s Army Group South. Hungary’s contribution included the 40,000-man Gyorshadtest, or “Rapid Corps.” Considered the most elite organization in the Hungarian Army, it was hardly “rapid.” A late start to its mobilization had left the Gyorshadtest understrength—it contained just two barely mechanized brigades, a border guard brigade, a horse cavalry brigade, and a small air component. Antonescu, on the other hand, sent in his Third and Fourth Armies, comprising 13 divisions.

Despite its shortcomings and the severe losses it incurred, the Gyorshadtest performed well during Barbarossa’s initial stages, especially in the Battle of Kiev in October. However, attrition took its toll on the Hungarians. Casualties spiraled to nearly 30 percent, and most of their heavy equipment was lost. As the Axis offensive ground to a halt amid the drifting snow of the Russian winter, the Hungarians were able to withdraw to regroup, but Hitler made it clear to Horthy that he expected his support when operations continued in the spring of 1942.

THE FIRST COLD BLEAK DAYS of 1942 marked the beginning of a reversal of fortune for Miklós Horthy. On January 6, 1942, when Ribbentrop came to call on him in Budapest to discuss coming Barbarossa operations, Horthy was on the defensive, recalling that “there was a considerable gap between the contribution Hitler demanded of us and that which we were prepared to make.”

However, the German foreign minister replied that the Western Allies, which by then included the United States, “had gone so far in their reckless indifference as to promise the Communists a free hand in Europe in order to encourage the Soviets to make greater sacrifices.”

A chilling fear of the Communists had lingered with Horthy since the chaotic power struggles that had convulsed Hungary two decades earlier, and this trumped his hesitancy to go all-in with Hitler’s planned 1942 offensive. This plan, known as Fall Blau (Case Blue), called for a decisive offensive against the southern Soviet Union. Horthy committed Hungary’s Second Army, including the only Hungarian armored division, with around 200,000 troops—more than four times the number that had seen action in 1941.

When operations began in June 1942, the Second Army was attached to the German Fourth Panzer Army for the Battle of Voronezh, 300 miles south of Moscow, during which it was badly mauled. Nevertheless, the Hungarians pressed eastward, along with the Italian and Romanian armies, as part of the Wehrmacht’s Army Group South. Through the summer and into the fall, they pushed eastward on the road that would lead them to the place—and the disaster—called Stalingrad.

In November, as the Battle of Stalingrad grew intense, the Hungarians helped anchor the Axis line’s northern flank while the German Sixth Army spearheaded the drive into the city. A combination of determined Soviet counterattacks and bitterly cold winter temperatures took a toll on the Axis armies. On February 2, 1943, the Sixth Army, encircled inside the city, surrendered to the Soviets. Meanwhile, only 20 percent of the men in the shattered Hungarian Second Army made it home several months later.

In April 1943, Hitler met separately with Mussolini, Antonescu, and Horthy at Schloss Klessheim in Austria. Each man insisted to the Führer that the war was lost and pined for a way out. Hitler naturally disagreed and argued that his Axis partners were not pulling their weight. Horthy recalled Hitler complaining that the “Hungarian troops had fought badly during the previous winter offensive, to which I replied that the best of troops cannot put up a good show against an enemy superior in number and arms; that the Germans had promised us armored vehicles and guns but had not supplied them; and that the heavy losses of our troops were the best testimony to the strength of their morale.”

Hitler also demanded that the Jews in Hungary “must either be exterminated or put in concentration camps,” to which Horthy recalled that he “saw no reason why we should capitulate to Hitler and change our views on this subject.”

Although Horthy may not have signed on to the idea of Hitler’s “Final Solution,” he was far from a humanitarian. In his memoirs, he admitted that in October 1942, Hungary “had introduced a special levy on Jewish capital as a ‘war contribution’ and had also restricted the Jewish tenure of land.”

As the months dragged on, Horthy and Antonescu—the two archrivals who had cast their lot with Hitler because they feared the Soviets—now watched Germany’s armies, still containing small numbers of Hungarian and Romanian troops, in retreat. Meanwhile, Stalin’s increasingly powerful war machine was moving inexorably toward their borders.

One by one, Hitler’s Axis partners were falling away. In July 1943, Italian troops arrested and imprisoned Mussolini, and the Italians announced an armistice in September. Hitler intervened, occupied the country, rescued and released Mussolini, and continued to fight the Allies in Italy.

Meanwhile, both Antonescu and Horthy battled the approaching Soviet armies—while simultaneously making peace overtures to the Anglo-American Allies that they thought were secret. Hitler found out and, in March 1944, summoned Horthy to Klessheim—while at the same time quietly ordering German troops to occupy Hungary under Operation Margarethe. When Horthy returned to Budapest, he was met by German soldiers. Though he was allowed to stay on as regent, he was compelled to reshuffle his government. Horthy’s party had controlled the National Assembly for years, but in the previous election, the fascist Arrow Cross Party and their allies had taken about 20 percent of the seats. It was Operation Margarethe that finally put the Arrow Cross in full control. The admiral was now a puppet.

Antonescu fared even more poorly. In August 1944, King Michael had him arrested and Romania switched sides. With Soviet help, Michael then made a move to “liberate” the part of Transylvania that Hitler had given to Horthy in 1940.

By September 1944, Germany’s Axis partners in Europe could be counted on the thumbs of one hand. Only Hungary remained, but Horthy was now at war with Romania and so desperate to shake his ties with Hitler that he was sending secret emissaries to Moscow.

On October 15, as Horthy went on the radio to announce that he had signed an armistice with the Soviets, the infamous SS commando leader Otto Skorzeny was already in Budapest to execute Operation Panzerfaust (Armored Fist) and seize control of the country. He took Horthy into custody and sent him to Schloss Hirschberg in Bavaria with orders that he be shot before he could be taken by the Allies. Horthy would never see Hungary again.

Hungarian and German troops now faced off against advancing Soviet and Romanian forces in a desperate final campaign. Budapest fell on February 13, 1945, after a bloody 50-day siege.

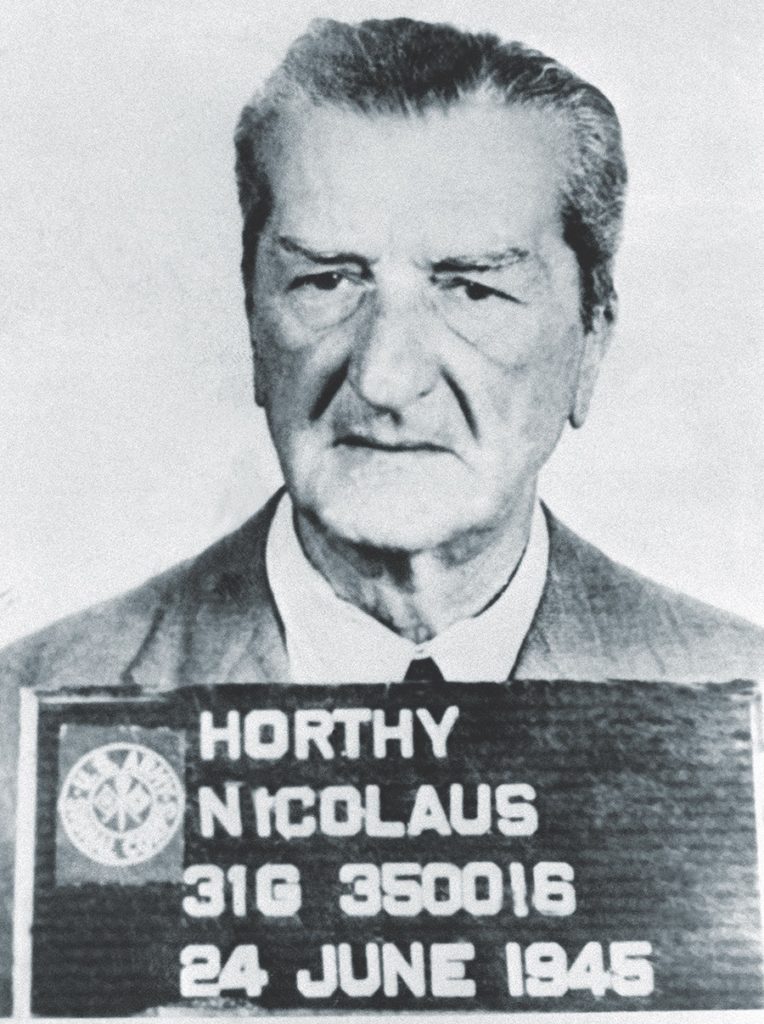

JUST AS HE HAD BOUNCED BACK from the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s collapse after World War I, though, Horthy managed to survive the calamitous climax of World War II. Hitler’s orders to the SS to kill him had yet to be carried out when the U.S. Army’s 36th Infantry Division arrived at Schloss Hirschberg on May 1, 1945.

Initially, the Allies imprisoned Horthy in Nuremberg, but in December 1945 they moved him to a house near Schloss Hirschberg where his wife had taken up residence after the Americans arrived. Here the two remained, literally living off care packages and the largesse of friends. As had been the case so often in his life, Horthy was in the right place at the right time. The Soviets had let it be known that if he were to be released from his American house arrest, he had a date in a Budapest courtroom for a trial with a preordained verdict. A similar fate did befall Ion Antonescu, who was tried and executed in Romania in 1946.

Meanwhile, the borders of Hungary, which Horthy had worked so hard to expand, were returned, with a few minor adjustments, to where they had been in 1920—and so they remain today.

In December 1948, the Americans allowed Horthy and Magdolna to travel to Switzerland, where their son knew the Portuguese ambassador. Visas were eventually arranged, and they traveled onward, via Genoa, Italy, on a slow boat to Portugal.

As guests of Portugal’s authoritarian prime minister Antonio Salazar, the couple settled into Casa San Jose, a comfortable, flower-covered villa in Estoril, an upscale western suburb of Lisbon. At last, the long-landlocked admiral had a refuge with a view of his first love, the sea.

From the Strait of Otranto to his triumphant ride into Komárom, Horthy had always been in the right place at the right time. Spared the wrath of the Guadalcanal islanders who later slew his geologist colleague, he went on to dodge the bullet promised him by the SS as well as a Soviet noose. Now, he would spend the rest of his days anguishing over the Communists then in control of Hungary and writing his memoirs. These were published shortly before his death in February 1957. ✯

This article was published in the December 2020 issue of World War II.