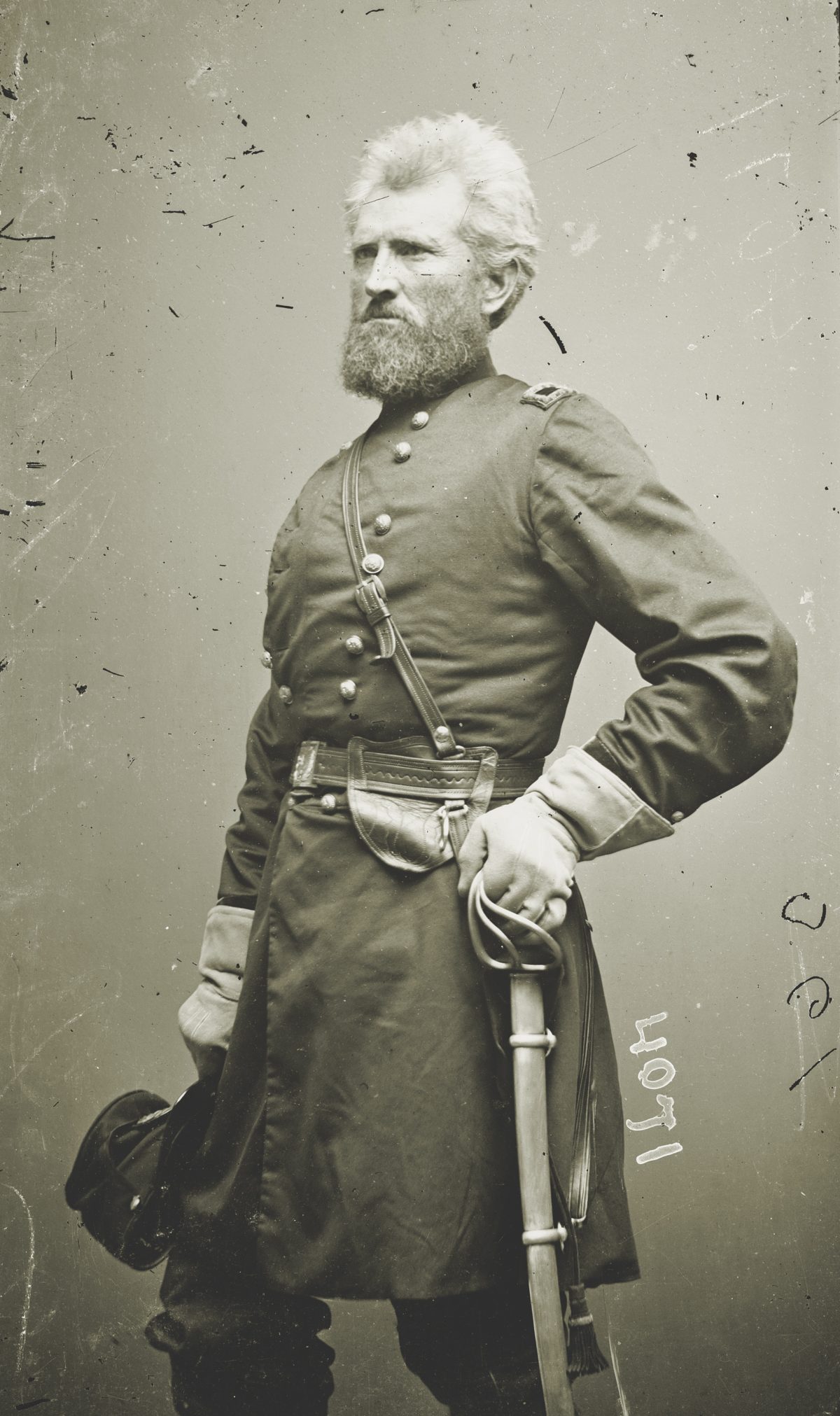

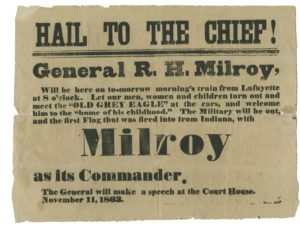

In the final hours of Union Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy’s life, with family gathered at his home in Olympia, Wash., the 73-year-old veteran had a singular focus—making certain that history did not judge him harshly for his defeat at the Second Battle of Winchester during the Confederate advance to Gettysburg in June 1863. On March 28, 1890—the day before his death—Milroy, according to a newspaper correspondent, “sat up all day…and dictated matter…touching upon the supreme event of his life, the battle of Winchester.” As Milroy spoke to A.S. Austin, a justice of the peace in Olympia, and May Sylvester, who was collaborating with Austin “in compiling a volume of the general’s military memoirs” (unfortunately never completed), the “Gray Eagle” stated emphatically that he was not ultimately responsible for the disastrous Union defeat at Winchester on June 13-15, 1863.

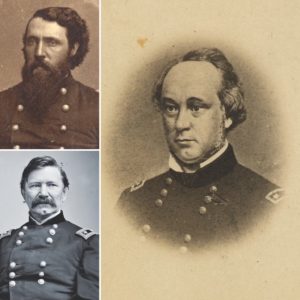

Throughout Milroy’s occupation of Winchester in the first half of 1863, General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck fretted for the safety of Milroy’s command. On April 29, Halleck reminded Milroy’s immediate superior Maj. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, commander of the Middle Department headquartered in Baltimore, that Winchester and its immediate environs was “no place to fight a battle. It is merely an outpost, which should not be exposed to an attack in force.” One month later, in the wake of the Army of Northern Virginia’s momentous victory at Chancellorsville, Va., Halleck’s anxieties about the safety of Milroy’s garrison neared a fevered pitch. He warned Schenck that “forces at Harpers Ferry, the Shenandoah Valley, and Western Va., should be on the alert and prepared for attack.”

Beyond Halleck’s warnings, Milroy’s Jessie Scouts—Union soldiers who donned Rebel uniforms and infiltrated Confederate lines to gather information—reported regularly in Chancellorsville’s aftermath that Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army was on the move and that Milroy’s command should expect an attack of some form. Colonel Joseph Warren Keifer, who “was given special charge” of these scouts in May, believed the evidence compelling. “So uniform were their reports as to the proposed attacks that I gave credence to them, and advised Milroy that unless he was soon to be largely reinforced it would be well to retire from his exposed position,” he explained.

Milroy, however, refused to believe the reports. Intent on remaining in the lower Shenandoah Valley to protect the area’s Unionist civilians and to continue implementing the Emancipation Proclamation, Milroy was convinced the information was inaccurate. By the first week of June, intelligence gathered by scouts revealed that the Confederate forces would reach Winchester on June 10. Recalled Keifer: “I gave this information to Milroy, but he still persisted in believing the whole story was gotten up to cause him to disgracefully abandon the Valley.”

When June 10 came and went without incident, Milroy was only further buoyed in his belief “that Lee would not dare to detach any part of his infantry force from the front of the Army of the Potomac.” But as the Gray Eagle nestled into a false sense of security, Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps spearheaded Lee’s advance west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. While Ewell’s command marched toward the Shenandoah Valley, Schenck’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. Donn Piatt, arrived in Winchester to inspect Milroy’s position. After examining Milroy’s defenses—Star Fort, Fort Milroy (Main Fort), and West Fort—Piatt seemed convinced by the time he departed Winchester on June 11 that Milroy’s position was strong. “All looks fine,” he telegraphed Schenck. “Can whip anything the rebels can fetch here.”

Although Piatt was initially confident in Milroy’s ability to defend Winchester, his perspective changed—undoubtedly because of a message sent by Halleck during Piatt’s return trip to Baltimore that noted, “Harpers Ferry is the important place, Winchester is of no importance other than as a lookout.”

Piatt sent a note to Milroy instructing him to take steps for an immediate withdrawal from Winchester. Incensed, Milroy wired Schenck, “I think I have sufficient force to hold this place safely.” On June 12, Schenck ordered Milroy to “make all the required preparation for withdrawing,” but also instructed the Gray Eagle to “hold” his “position in the meantime…but await further orders.”

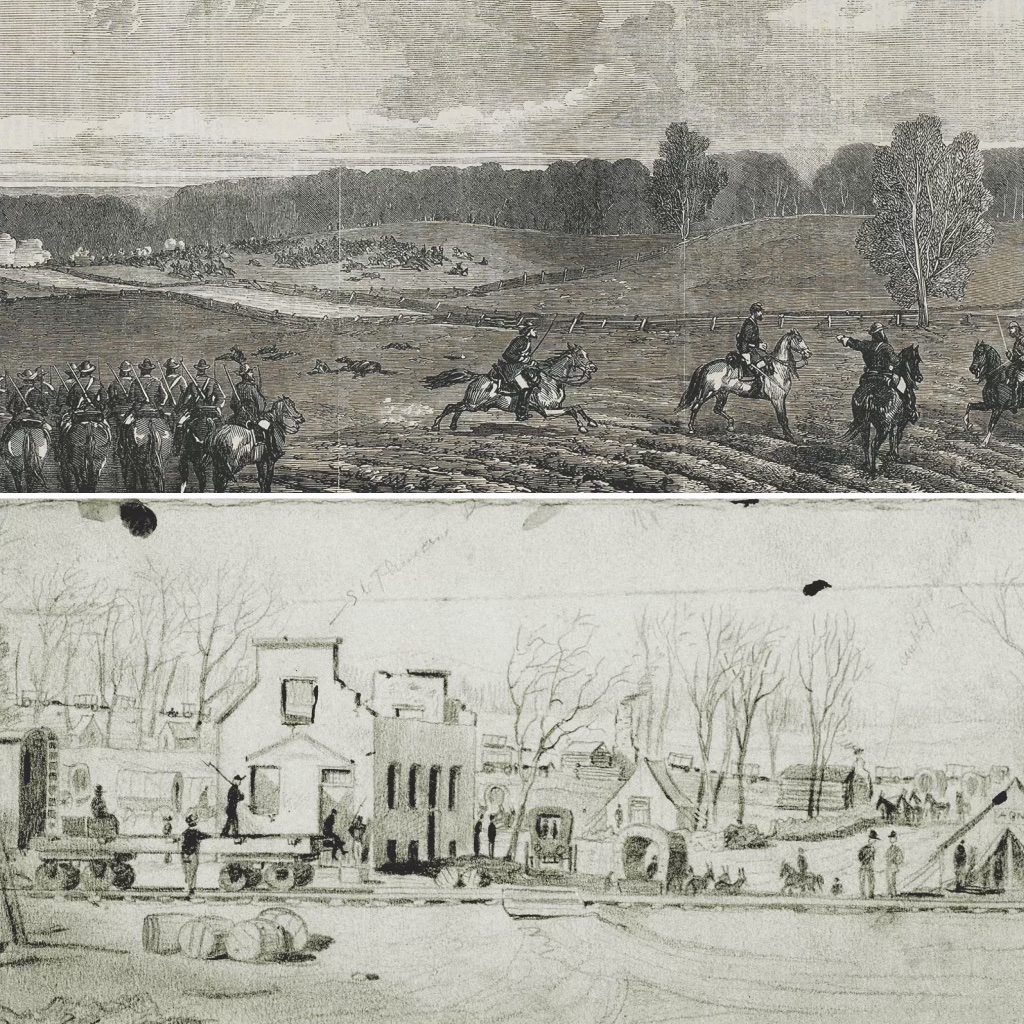

As the telegraph lines buzzed with messages between Halleck, Piatt, Schenck, and Milroy on June 12, Ewell’s Corps appeared 15 miles south of Winchester in the small hamlet of Middletown—where in October 1864 Union forces would win a decisive victory at the Battle of Cedar Creek and end the Confederacy’s dominance in the Shenandoah Valley. Fighting with elements of Ewell’s command intensified on June 12 in Middletown, Kernstown and Winchester’s southern outskirts. The following day, Schenck was pressured by President Abraham Lincoln to “Get Milroy from Winchester to Harpers Ferry if possible,” and finally ordered Milroy’s withdrawal. Milroy, however, would never receive a critical series of messages from Schenck, as Ewell’s troops had torn down the telegraph lines.

Without an opportunity to repair the lines, Milroy drew his command into his fortifications and awaited Ewell’s attack on June 14. After Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division launched a successful attack against the smallest of Milroy’s defenses, West Fort, followed by hours of artillery bombardment between Confederate guns in West Fort and the Baltimore Light Artillery battery in Star Fort, Milroy understood his situation was dire. About 9 p.m., the general held a council of war with his brigade commanders, finally conceding that the withdrawal to Harpers Ferry was the Federals’ best alternative.

After destroying what could not be carried and spiking the guns, Milroy’s command marched north in the early morning hours of June 15; however, Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s Division intercepted Milroy’s command near Stephenson’s Depot. Although Milroy avoided capture, 4,030 of the troops in his 7,000-man command were not so fortunate that morning. In addition to the capture of more than half of Milroy’s force, 95 Union soldiers were killed and 348 wounded during the multiple-day battle. Confederate casualties totaled only about 2 percent of Ewell’s command: 47 killed, 219 wounded, and three missing.

At about the time Milroy gathered his brigade commanders the night of June 14 to decide what should be done, Lincoln, Halleck, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles met to discuss the movement north of Lee’s army. Although there had been no communication with Milroy for two days and Johnson’s Division had not yet delivered the final crushing blow to the Federal force in Winchester, Lincoln had begun to fear that Milroy would inevitably suffer the same fate that Colonel Dixon Miles’ command had at Harpers Ferry during the Antietam Campaign the previous September. According to Welles, Lincoln informed the group: “It is Harper’s Ferry over again.”

Welles suspected that if things indeed went badly at Winchester, Milroy would become “the scapegoat, and blamed for the stupid blunders, neglects, and mistakes of those who should have warned and advised him.”

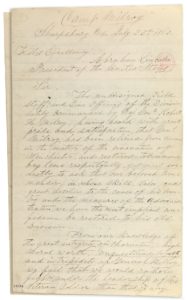

Welles’ suspicion proved true when Halleck ordered Schenck to place Milroy under arrest on June 27. Now confined in Baltimore, Milroy began a fierce letter-writing campaign to secure his release. As Milroy penned letters to Lincoln, Halleck, and Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher—a fellow Hoosier—to restore him to command rather than keep him in “this disgraceful inactivity during the present terrible crisis of my country,” he watched events unfold in southern Pennsylvania and quickly recognized the significance of the Union Gettysburg victory. On July 13, 1863, Milroy opined in a letter to Lincoln that the Army of the Potomac’s victory “will complete the destruction of Lees [sic] army.”

Milroy was incensed that his arrest had prevented him from participating in such a momentous battle. “Having been denied the privilege of participating in the glorious battle of Gettysburg…,” he wrote Lincoln, “adequate Justice cannot now be done me.” In the same letter, Milroy pleaded with Lincoln to “be restored to my old command” or appoint him to “some other command,” and also asked the president to be permitted to publish his “official report” of what had transpired at Winchester, which Milroy had written on June 30. All his requests fell on deaf ears.

Confined and silenced, Milroy’s reputation suffered significantly throughout the summer as newspapers across the North branded him a coward and contended that he was singularly responsible for the catastrophic defeat at Winchester. For instance, an Ohio correspondent identified only as A.B.M., noted that “the unaccountable defeat of Milroy in which he lost more than half of his command…smacks of cowardice…the fault lies with the commanding officer.” Comments such as these not only incensed Milroy, but also many of those whom he commanded at Winchester.

Although some of Milroy’s men relented that his Second Winchester performance had been poor, plenty detested the criticisms leveled against him by the press. When a veteran of the 116th Ohio Infantry read A.B.M.’s remarks, the soldier, who identified himself as “For Milroy,” came to his former commander’s defense. “No one who knows Milroy will ever call him a coward. And no one will make this charge a second time in hearing of any of the men of his old Division.”

Similarly, a contingent of officers from Milroy’s division sent a letter to Lincoln on July 23, 1863, hoping to convince the president of the general’s value as a field commander. “We feel that we would rather fight under the leadership of this veteran soldier than that of any other commander,” the officers wrote from “Camp Milroy” in Sharpsburg, Md. The officers continued in praise that “no other man living can inspire the officers and men of this Division with the same amount of courage, zeal and enthusiasm in the work of crushing out this infamous rebellion.”

‘Heroes of the Highest Magnitude’

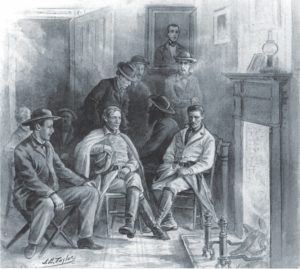

As artist-correspondent James E. Taylor sat in Joseph Denny’s home in Winchester, Va., in early December 1864, conversing with several others in Denny’s sitting room, two men dressed, as Taylor recalled, “in Confederate uniforms and overcoats,” entered the room quietly, took a seat, and enjoyed “the comforting warmth of the blazing logs in the great open fireplace.” Taylor wondered about the “status of the mysterious visitors equipped for the warpath.” Denny, one of Winchester’s Unionist sympathizers, informed Taylor that they were “Jessie Scouts.”

Formed in 1861 by Union Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont while in command of the Department of the West, the scouts wore Confederate uniforms, carried appropriate documents, and aided in gathering intelligence for Frémont. Named for Frémont’s wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, the Jessie Scouts were initially commanded by Charles C. Carpenter, who one Kansas newspaper correspondent wrote in the early autumn of 1861 could “[im]personate even the devil when necessary for the success of his schemes.”

When Frémont took command of the Mountain Department in March 1862, he brought Carpenter and 25 Jessie Scouts east with him knowing “that the safety and efficiency of his army in a wild wooded and rugged region,” depended “upon the accuracy with which he received information of the plans and movements of the enemy.” In late June 1862, after Frémont resigned his command in protest of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s appointment as commander of the newly created Army of Virginia, the Jessie Scouts came under General Milroy’s command, which served as part of Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel’s 1st Corps.

Although the Jessie Scouts’ connection with Frémont ended in late June 1862, various Union commanders who operated in Virginia and what in 1863 would become West Virginia—including Milroy and Brig. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan—understood the usefulness of such scouts who dressed in “the Rebel’s uniform, from hat to boots…[who] went through the country, through the [Confederate] army, in camp or on the march, gathering much valuable information…without creating any alarm.”

Milroy used them throughout his half-year tenure in the northern Shenandoah Valley. Milroy’s Jessie Scouts not only provided him with valuable information, but one, Archibald Rowand Jr., saved Milroy’s horse, “wounded and hobbling,” during the Second Battle of Winchester. (In 1873, Rowand received the Medal of Honor for his gallant acts later in the conflict.) Feared and detested by Confederate soldiers and civilians alike, to those who supported the Union cause, the Jessie Scouts proved “heroes of the highest magnitude…a noble and courageous character…patriotic, quick-witted, intelligent and terribly in earnest.” —J.A.N.

In addition to refuting the charge that Milroy had acted pusillanimously, an unidentified veteran from the 116th Ohio argued, in a letter penned to an Ohio newspaper, the Messenger, from Martinsburg, W.Va., on August 23, 1863, that the fighting in which Milroy’s division engaged as early as June 12 proved significant in delaying the Army of Northern Virginia’s advance into Pennsylvania and that, had Ewell’s Corps not confronted any resistance, the outcome of the Gettysburg Campaign may well have been considerably different. “Was it cowardly to check the advance of Lee’s army for three days, and thus give the Potomac army time,” the Buckeye pondered.

The Ohio soldier, who signed his letter to the Messenger “Yours for Milroy,” was not the only one to claim in Gettysburg’s aftermath that the general’s efforts were ultimately beneficial to the defeat of Lee’s army. On August 18, 1863, the 10th day of the court of inquiry investigating the Union commander’s conduct at Winchester, Milroy argued the same point. “I checked the advance of Lee’s army three days, that was certainly something for the country,” he stressed. “If they had been allowed to go on, they would have had three days longer for pillage and robbery in Pennsylvania, and probably ten times as much property as I lost would have been destroyed in that time.”

Milroy and the 116th Ohio soldier could, of course, be accused of partiality, but Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt could not. Nearly one month after Milroy made that statement before the court of inquiry—a proceeding that summoned 16 witnesses—Holt penned his “Review” of the “Record of the Court of Inquiry Relative to the Evacuation of Winchester by the Command of Maj. Gen. R.H. Milroy.” The 12-page review not only exonerated Milroy, a conclusion President Lincoln affirmed on October 27, but seemed to suggest that the presence of Milroy’s force at Winchester had, as the Gray Eagle contended, proved beneficial. Holt concluded that the “strategic view” advanced by Milroy “may, perhaps have some weight.”

Piatt echoed Holt’s sentiments in declaring, “The check that the rebels received at [Second] Winchester must have been of importance to us.”

Despite Milroy’s exoneration and Lincoln’s statement in support of the inquiry’s findings “that serious blame is not necessarily due to every serious disaster,” the battle of public perception remained to be fought. Some histories of the war do little to bolster any of the claims made by Milroy, his veterans, or Holt. For example, William Swinton’s Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac entirely discounted the court of inquiry’s findings and charged that Milroy’s “defence of the post intrusted to his care was infamously feeble, and the worst of that long train of misconduct that made the Valley of the Shenandoah to be called the ‘Valley of Humiliation.’”

For the remaining 27 years of Milroy’s life and beyond, those who fought with Milroy at Winchester vociferously defended his conduct and continued to advance the notion it was wrong to downplay the battle’s importance. Regimental historians such as the 116th Ohio’s Thomas F. Wildes, the 18th Connecticut’s William Walker, the 87th Pennsylvania’s George Prowell, and Frederick Wild of the Baltimore Light Artillery reiterated that claim.

“Had it not been for the check given Lee’s army during the 12th, 13th, and 14th of June…Gettysburg would have been fought three days’ march further north,” Wildes penned in 1884. The following year, Walker, the chaplain of the 18th Connecticut, echoed that Second Winchester was “instrumental in checking the advance [of the] foe for three days, and thereby ensuring the Union army victory at Gettysburg.” Walker took the argument one step further, noting that had Milroy’s command “not stood fast…the enemy would have had comparatively an easy task to have reached Gettysburg three days sooner, and who could have computed the results to Harrisburg, Philadelphia, and Baltimore?”

In 1903, Prowell leaned on the court of inquiry report and Holt’s conclusion to cast the argument in Milroy’s favor. Nearly a decade later, Wild concluded in his history of the Baltimore Light Artillery that “it was for the best, after all, that we staid [sic] at Winchester as we did.”

Veterans such as the 87th Pennsylvania’s John M. Griffith berated histories in an article he penned in the National Tribune in 1909 that did not properly credit “that little force at Winchester…with the important part it played in the Gettysburg campaign. The under dog in the fight seldom does receive much attention.”

Several months later, R.H. McElhinny, a veteran of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, echoed Griffith’s criticism of histories that overlooked the fight at Winchester. “The historians say nothing about it,” McElhinny complained. “If Lee had slipped past Winchester quietly[,] Gettysburg would never have been a noted battlefield.”

Despite the efforts of Milroy’s veterans to redeem their general’s reputation and in turn highlight their role in the Gettysburg Campaign, detractors continued to diminish Milroy’s reputation and downplay the role his command had played. Approximately two weeks after Milroy’s death, a columnist for the Morning Oregonian—at a time when newspapers eulogized Milroy and lauded his commitment to the Union’s preservation and slavery’s destruction—chastised those who defended Milroy’s conduct at Winchester and ridiculed the “claim that Winchester…fixed the fate of Gettysburg….The truth is that Milroy’s holding on at Winchester had no influence whatever upon the fate of the campaign except needlessly to swell its losses.”

Historical judgments are difficult things. While the impact of Milroy’s defense of Winchester on the Union victory at Gettysburg could be debated to the point of exhaustion by modern-day historians, there is no denying that Milroy, individuals whom he commanded, and the inquiry that exonerated him believed there some strategic advantage to what Milroy’s command did at Winchester. The conundrum is quantifying the extent of that benefit. For John Laird Wilson, who authored Pictorial History of the Great Civil War in 1878, the middle ground seemed the best course. “General Milroy was severely taken to task for his conduct at Winchester” and “was vindicated by others,” Laird wrote.

For Milroy and his allies, however, there was never any middle ground. They believed, as did 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry Captain Peter Bricker, that when “the past historian will review his work,” “the future historian pause, [and] reflect,” and “the great artist…dwell so rapturously upon the battle of Gettysburg” and “applaud its heroes” that they will mark Winchester “as the preliminary part of this famous battle” and “pause sufficiently long to write upon the surge and swell of the wave that humble name of one of the bravest of the brave, Milroy.”

Jonathan A. Noyalas, director of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute and a history professor at Shenandoah University, is the author or editor of 14 books, including, “My Will Is Absolute Law”: A Biography of Union General Robert H. Milroy and Slavery and Freedom in the Shenandoah Valley During the Civil War Era.