Anyone interested in the military history of the Civil War owes a debt to William F. Fox and Frederick H. Dyer. Both Union veterans, they engaged in almost unimaginably tedious research, organized a mass of statistical and descriptive information, and compiled their findings in accessible formats. Although more recent publications that draw on manuscript materials unavailable in the late-19th and early-20th centuries have provided a fuller statistical picture of many particular aspects of the war, they have not superseded the pioneering volumes by Fox and Dyer as invaluable reference works.

Fox’s Regimental Losses in the American Civil War 1861-1865, an oversize volume of nearly 600 pages published in 1889 and reprinted by Morningside Bookshop in 1974, originated in “the patient and conscientious labor of years” marked by “[d]ays and often weeks…spent on the figures of each regiment.” An officer in the 107th New York Infantry during the war, Fox devoted more than half of his text to a long chapter titled “Three Hundred Fighting Regiments—Statistics and Historical Sketch of Each.” This roster featured regiments “which sustained the heaviest losses in battle.”

The cutoff was for regiments with 130 killed or mortally wounded for the war, “together with a few whose losses were somewhat smaller, but whose percentage of killed entitles them to a place in the list.” Aware that some veterans might take offense at having their units excluded (his own 107th New York did not qualify), he acknowledged that other regiments undoubtedly “did equally good or, perhaps, better fighting, and their gallant service will be fully recognized by the writers who are conversant with their history.”

Each unit’s page offers a table of casualties by company for the war (killed and mortally wounded in action and deaths due to disease and accidents), percentage killed during the entire conflict, losses at most important battles, and “Notes” filled with miscellaneous information. Every regiment of the Iron Brigade made the list, headed by the 7th Wisconsin’s 281 killed or mortally wounded in action as the highest total and the 2nd Wisconsin’s 19.7 the highest percentage loss. Nineteen of the 20 regiments with the most combat fatalities served in the Army of the Potomac. Among African American units, Fox included the 79th USCT, which served in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the 8th USCT, and the famous 54th Massachusetts.

The “Notes” sections reward a close perusal. Regarding the largely forgotten 137th New York Infantry, which under Colonel David Ireland anchored the Union right on Culp’s Hill on July 2, 1863, Fox wrote: “This regiment won special honors at Gettysburg, then in Greene’s Brigade, which, alone and unassisted, held Culp’s Hill during a critical period of that battle against a desperate attack of vastly superior force.” Fox also commented about the far more celebrated service of the 20th Maine Infantry at the other end of the Union line: “Chamberlain and his men did much to save the day at Gettysburg, by their prompt and plucky action at Little Round Top. Holding the extreme left on that field, they repulsed a well-nigh successful attempt of the enemy to turn that flank, an episode which forms a conspicuous feature in the history of that battle.”

Apart from the 300 fighting regiments, Fox tabulated casualties by regiments in one battle, for the war, and in comparison to losses in European armies. He devoted chapters to Union corps, to “Famous Divisions and Brigades,” and to “The Greatest Battles of the War.” Primarily interested in the U.S. side of the conflict, he also allocated one chapter to Confederate losses and strengths.

Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, a massive tome of nearly 1,800 pages, was published in 1908 and reprinted in three volumes in 1959 (Thomas Yoseloff; introduction by Bell I. Wiley) and in two volumes in 1978 (Morningside; introduction by Lee A. Wallace Jr.). Dyer’s service had been in the ranks of the 7th Connecticut Infantry, first as a young drummer boy (he enlisted under the name Frederick H. Metzger) and then as a private.

His preface explained why he undertook the project. Pronouncing the 128-volume Official Records “practically impossible to use except by a specialist,” he sought to present “certain statistics and data of great interest and value” in a more usable fashion. Divided into three parts, the Compendium provides detailed information about the organization and commanders of U.S. military forces by department, army, corps, division, brigade, and regiment, followed by a list of more than 10,000 military events arranged by state that includes date, nature (battle, skirmish, siege, action, affair, etc.), location, and troops engaged. A very useful table on “National Cemeteries and Their Locations” provides the number of known (176,397) and unknown (148,833) burials as of the early 20th century, informing readers that the figures included 9,300 Confederates.

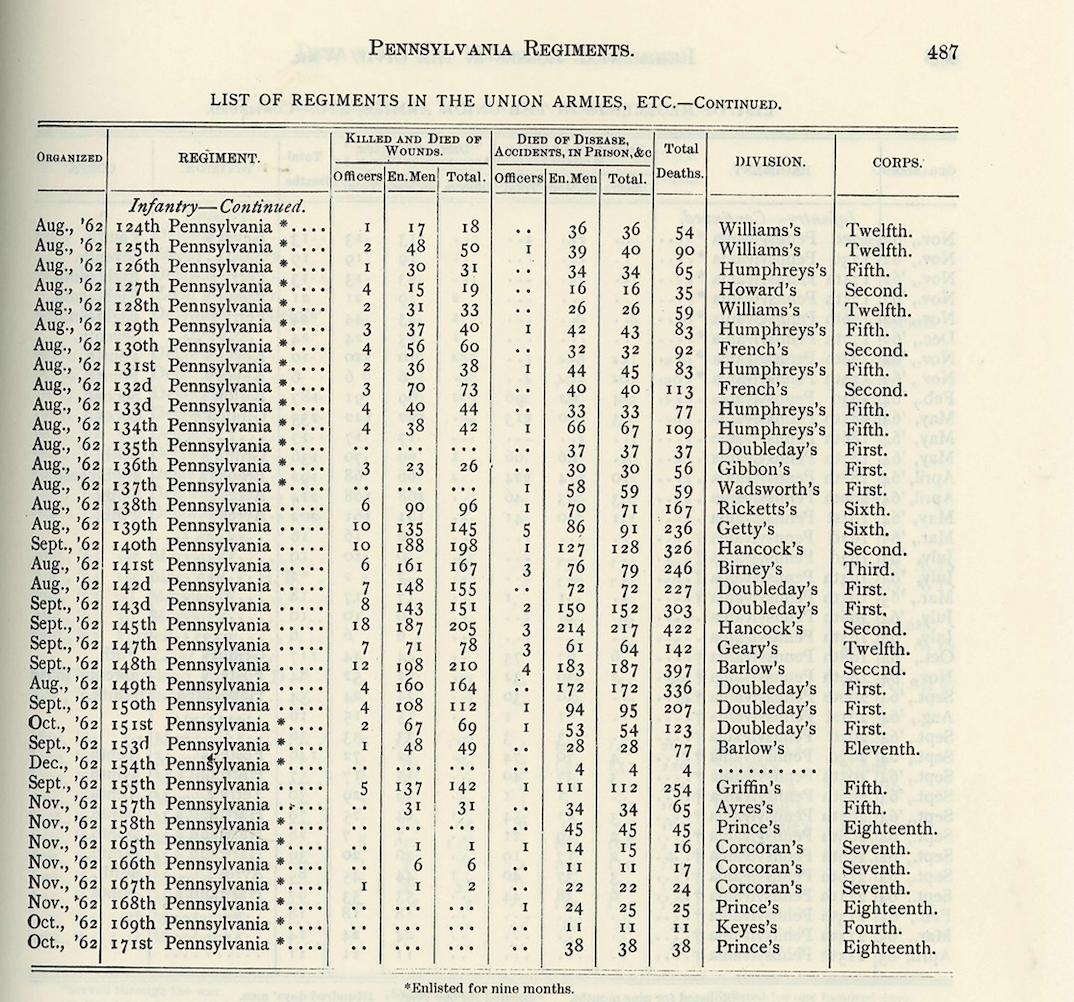

Brief histories of nearly 2,500 Union regiments and artillery batteries fill the last 750 double-column pages of the Compendium. Arranged by state or territory and varying in length from a few lines (e.g., Ohio’s 2nd Independent

Battalion of Cavalry and New York’s 28th Independent Battery Light Artillery) to more than a page and a half (for example, 6th Michigan Cavalry and 47th Illinois Infantry), the entries begin with the date of organization, trace all deployments during the war, and conclude with the date of mustering out. Dyer also provided figures on deaths due to wounds and disease for officers and enlisted men. After more than a century, this last section of the Compendium remains the most convenient place to look for basic information about Union regiments and batteries.

One bibliographer noted that Dyer inevitably recorded “a few incorrect dates, a number of incorrect assignments, and omitted some commanders” but insisted that the work remains “among the most comprehensive, important, and useful of this type.” Bell Wiley reached a similar conclusion, pronouncing the Compendium “outstanding from the standpoints of organization, scope, comprehensiveness and richness in detail. It is unquestionably the most valuable Civil War reference work complied by one author.” I keep copies of both Fox and Dyer close at hand in my own library, shelved with other titles I often consult. For anyone whose bookcases lack space for additional large volumes, full texts of Regimental Losses and the Compendium await interested users online.