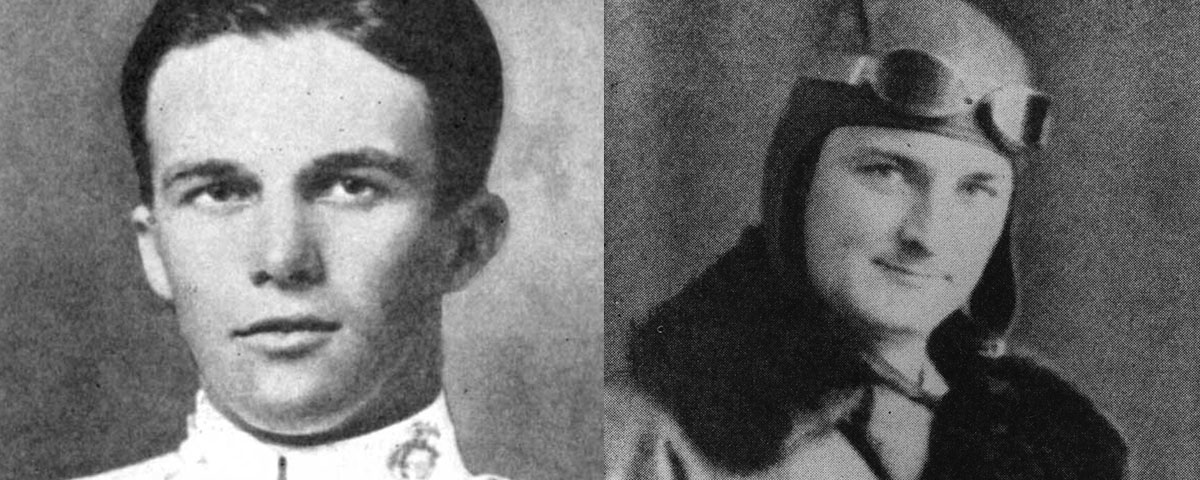

In the annals of aviation history, the aerial dogfights of World War I stand out for the sheer brutality, tenacity, and possible insanity of the combatants. And while names like Raoul Lufbery, Eddie Rickenbacker, and the “Red Baron” Manfred von Richthofen are noteworthy, there were many other heroes of the air. Two of those men, Ralph Talbot and Robert Robinson, certainly made their case.

Talbot and Robinson made up the crew of a Marine Corps Airco DH-4 serving with the 1st Marine Aviation Force in late 1918.

Talbot, the pilot of the aircraft, first began flying while a member of Yale’s Artillery Training Corps. In October 1917 Talbot enlisted in the Navy with the hopes of becoming a Naval Aviator. Upon completion of his training however it became apparent that serving in the Navy was no way to get into active combat in Europe. Talbot decided to resign his Navy commission in order to join the Marines heading for France. Talbot was assigned to Squadron C, 1st Marine Aviation Force and shipped out to France in July 1918.

Robinson, the observer and rear-gunner of the airplane, was what was known then as a “flying sergeant” – maintaining the airplane on the ground before climbing aboard to do battle in the air. Having enlisted in May 1917, Robinson quickly ascended to the rank of gunnery sergeant.

By October 1918, the two men found themselves flying bombing and observation missions over German lines. And on October 8, while conducting an air raid alongside the Royal Air Force’s Squadron 218, they got into their first serious scuffle. Their plane was singled out by nine German scout planes and relentlessly attacked. Robinson, manning a Lewis gun in the rear position, sent one of the attackers earthward. Talbot fired the forward-facing guns as the pilot downed another of their attackers before making good on their escape.

Six days later Talbot and Robinson joined an air raid over Pittham, Belgium. Their plane, along with another, experienced engine trouble and dropped out of formation. Almost instantly they were pounced on once again by German fighters. Twelve enemy aircraft swarmed the sky around them. They quickly lost contact with the other aircraft. The two men were all alone and severely outnumbered.

Undaunted, Robinson swung his Lewis gun into action and shot one of the German attackers out of the sky. As the rest of the Germans pressed the attack his gun jammed. Before he could clear the jam, a bullet tore through the elbow of his left arm nearly severing it. Talbot then, according to his Medal of Honor citation, “maneuvered to gain time for [Robinson] to clear the jam with one hand, and then [return] to the flight.”

With his one good arm, Robinson cleared the jam in his weapon and began firing at the Germans once again – keeping them at bay – while Talbot searched for a way out of their predicament. But before they could escape, two more bullets slammed into Robinson hitting him in the stomach and hip, rendering him unconscious.

With his tail now dangerously exposed Talbot was running out of options. One German plane stood between Talbot and friendly lines. With a burst from his machine gun, in a fortuitous mix of skill and luck, he sent the German down in flames before diving to 50 feet and flying as fast and low as his failing engine would carry him.

Talbot landed at the nearest hospital so Robinson could be treated before returning to his aerodrome. After numerous and extensive surgeries Robinson would recover from his wounds. Talbot, however, was tragically killed a few days later, on October 25, when his plane crashed on take-off during a test flight.

In two separate engagements the two men had faced over 20 German adversaries, shot down four of them, and lived to tell the tale. For their actions both men were awarded the Medal of Honor.