Sharpshooters wore camo and hefted state-of-the-art rifles with longer, flatter trajectory

The green-clad soldiers waited patiently in the shadows of the Pennsylvania woods. Their uniforms blended into the summer foliage, and the deep shade prevented the bright sun from reflecting on the barrels of their deadly rifles. It was a warm day in early July 1863. As the marksmen positioned just south of the town of Gettysburg scanned their surroundings for signs of Confederate forces, they drained their canteens and waited for the enemy to appear. The soldiers were members of Berdan’s Sharpshooters, an elite infantry unit equipped with fine breechloading percussion rifles—the Sharps Model 1859. The Rebels learned soon enough to fear this enemy.

At the start of the conflict, Hiram Berdan, a 36-year-old New Yorker and nationally known marksman, believed his greatest contribution to the war effort would be the formation of a sharpshooting regiment made up of the best riflemen in the Northern states. After receiving formal approval from military authorities, Berdan opened regional competitions to decide who could join his ranks.

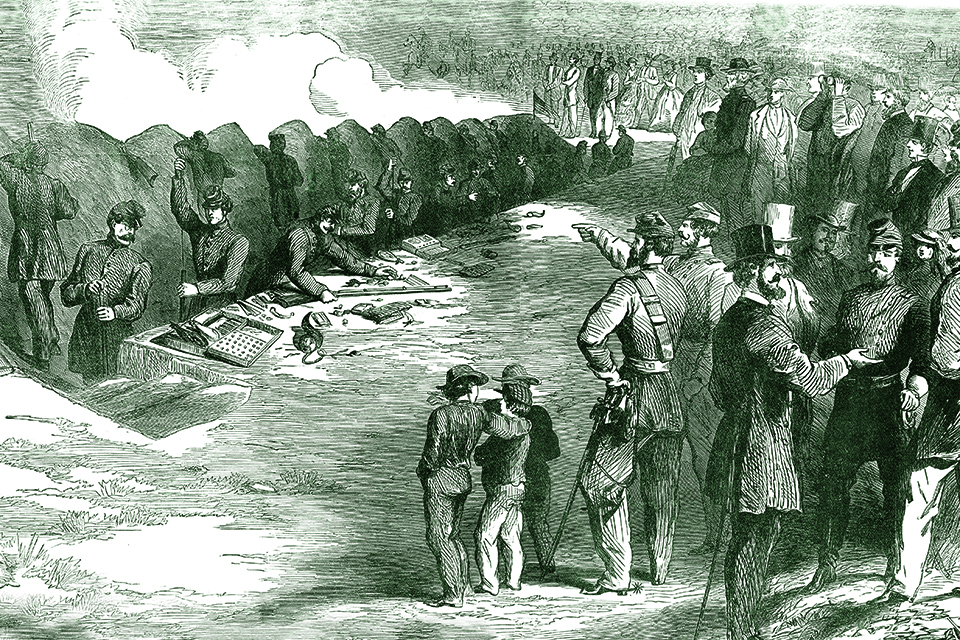

In the summer of 1861, Berdan’s recruiters scoured the Northern states for qualified candidates. At the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, in fact, the 2nd Regiment had representatives from Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Vermont. Men were given plenty of incentives to join the unit. Berdan offered enlistment bonuses and even compensation for those shooters who brought their personal target rifles. The distinctive uniforms they would wear was another advantage: dark green caps, trousers, and coats, essential in helping them blend in with the scenery while operating among trees and brush.

Acceptance, however, was hardly guaranteed. To qualify as a sharpshooter, all prospects had to place 10 consecutive shots inside a 10-inch circle (roughly the size of a dinner plate) from 200 yards at rest (or 100 yards off hand) without the aid of a telescopic sight. Ultimately, some 2,000 marksmen qualified. As early as August 1861, they were assembled into what became the 1st and 2nd United States Sharpshooters.

At first, Berdan wasn’t certain what weapon he wanted his men to carry. He had initially placed an order with Brig. Gen. James W. Ripley, head of the U.S. Army Ordnance Department, for 750 Springfield rifles, which Berdan felt would serve in an interim capacity until a first-class alternative weapon became available. Then, while the sharpshooters were in training at Fort Corcoran in Washington, D.C., a former gold miner and hunter named Truman Head joined their ranks. Given his West Coast background, the men quickly dubbed the new recruit “California Joe.”

“There is a new man here in my company that is all attention,” one sharpshooter wrote in his diary. “He is a craggy old monument from California and can shoot better than many as he was a bear hunter. He favors…an old Sharps and has told all that will hear that he will obtain a newer edition to fight rebels shortly.”

An outstanding marksman, Joe was disgusted with the old, cast-off guns that many of his fellow sharpshooters had been issued—mostly worn-out Halls rifles and smoothbore muskets. True to his word, he eventually bought the M-1859 Sharps. Berdan got to fire the rifle, and immediately ordered a thousand for his men. Because of a production backlog at the Sharps factory, though, he also arranged for a consignment of M-1855 Colt revolving rifles.

The men—to put it mildly—hated the Colt, finding it inaccurate, unreliable, and unsafe in the event of a chain fire (the accidental simultaneous discharge of all rounds in the weapon’s cylinder). After constant demands for a replacement, the Army replaced the detested revolving rifles for the M-1859 Sharps. In May 1862, the men finally had their new guns and, by June, a shipment of 200,000 cartridges.

Three features made the M-1859 Sharps such a fine instrument: loading design, action, and ammunition. The brainchild of Connecticut gunsmith Christian Sharps, his latest model was an outgrowth of his original 1848 concept for a percussion lock breechloader. At a time when most firearms loaded through the muzzle—utilizing an awkward combination of ball, powder charge, and ramrod—a gun that loaded from the breech offered numerous advantages, especially for the sharpshooter.

As true during the Civil War as it is today, sharpshooters depended on coverage and concealment. Standing a rifle on its butt and fumbling with powder, ball, and ramrod could betray one’s location to the enemy. Loading from the muzzle was an even more difficult procedure to perform from a prone position.

The breechloading design, on the other hand, enabled shooters to reload effortlessly regardless of how they were situated. They could load the single-shot Sharps while standing, kneeling, or prone, sending up to 10 well-aimed rounds downrange every minute—nearly triple a muzzleloader’s rate of fire.

The falling-breechblock action was another valuable element of the gun’s design that enabled the soldiers to reload quickly. A lever attached just forward of the trigger guard internally raised and lowered a rectangular chunk of metal known as a breechblock.

When closed, this piece sealed the rifle’s chamber and, upon firing, effectively transferred the recoil to the weapon’s stock.

The Sharps did not make use of a metal cartridge with a built-in primer, but it did use a unique cartridge that consisted of a bullet attached to a powder charge wrapped in paper or thin linen, and the consolidated round saved time during loading. The powerful .52-caliber, roughly one-ounce Sharps projectile left the muzzle at a scorching 1,200 feet per second, compared to the muzzle-loading Pattern 1853 Enfield’s 900 feet per second. The result was a flatter long-range flight trajectory along with a bit of surprise. As one Confederate soldier observed of the rifle’s supersonic round, “the [Sharps] bullet got to you before the report, but if it was a muzzleloader the report got to you before the ball.”

A double-set trigger system included a ‘hair trigger’ that increased accuracy. The Sharps was, indeed, a firearm built for discerning and deadly shooters.

Berdan’s men were soon able to test their breechloaders in battle. At Malvern Hill, Va., on July 1, 1862—the final clash in the Seven Days Battles—their pinpoint fire destroyed in only 10 minutes the 1st Richmond Howitzers of Colonel William Barksdale’s Brigade. “We went in a battery and came out a wreck” a Confederate gunner later wrote. “[W]e came out with one gun, ten men and two horses, and without firing a shot.”

The sharpshooters figured prominently again at the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. In the devastating fighting in and around the Cornfield, the 2nd had 13 officers killed and wounded, as well as 54 enlisted men killed, wounded, or missing.

One of those slain was 2nd U.S. Adjutant Lewis C. Parmelee, who took command of the regiment when Colonel Henry Post was wounded. When fired upon by Rebel troops after exiting the Cornfield, the 2nd “returned fire and the Confederates started to break, leaving ‘guns, knapsacks and everything that impeded their progress on the ground beside their dead and wounded comrades,’” writes Civil War historian Jim Woodrick, director of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

According to Woodrick, Parmelee seized a flag from a wounded enemy color-bearer and attached it to his sword to rally his men. He had advanced only a few steps, however, before he was struck down by gunfire, reportedly hit at least five times.

“[W]e shot our rifles today fiercely,” one sharpshooter wrote in his diary that day. “I saw Parmelee fall.”

Parmelee was one of nine members of the regiment to be buried on the battlefield after the battle, though his family later had his remains reinterred elsewhere.

The role Berdan’s men played in the Union victory at Gettysburg may well have been their most defining moment. During the critical fighting on July 2, the two regiments were part of Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward’s 2nd Brigade in the 1st Division of

Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles’ 3rd Corps. Ward was responsible for the extreme left of the Army of the Potomac’s defenses, and when Colonel John Buford’s cavalry was dispatched about noon to Westminster, Md., to “refit and reshoe” their mounts, Ward sent out eight companies of the 2nd Regiment to the southwest of his position.

Major Homer Stoughton, the 2nd’s commander, reported after the battle that he had been instructed by Berdan to place his men on Big Round Top, what he called Sugar Loaf Hill. He placed four companies straddling a crossroad whose trace today occupies Slyder Lane; one in a ravine at the base of the hill; and one on the brow of the hill, with “videttes” overlooking the ravine. Stoughton kept the two other companies in reserve, though they would be brought forward soon enough.

According to Gettysburg licensed battlefield guide Gary Kross, writing in Blue & Gray magazine: “The Sharpshooters usually deployed in no larger a group than ‘cells,’ where four men were responsible for each other during combat….The ‘videttes’ referred to by Stoughton on Big Round Top would have been comprised of a number of ‘cells’ in strategic positions along the western slope of the hill.”

A group of 15 men from several companies that had moved forward enough on Big Round Top witnessed the early-afternoon arrival of infantry of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s First Corps on the southern end of the battlefield, as well as the arrival earlier of Confederate artillery. When two Rebel scouts were captured, Adjutant Seymour F. Norton was able to report back to his superiors the escalating Confederate presence.

When Confederate artillery began moving into position on the southern end of Seminary Ridge, some of the batteries were placed immediately in front of members of Stoughton’s skirmish line. A few sharpshooters crept through the woods and deployed behind a stone wall before unleashing a quick salvo on a North Carolina battery under Captain James Reilly.

That seemingly minor disruption affected the preparations of Evander Law’s Alabama Brigade ultimately headed for Little Round Top. Without informing his regimental commanders of his intent, Law detached about 200 men from five of his companies to seek out and confront the unseen force that had just fired on Reilly’s guns. The sharpshooters, however, had already pulled back up Big Round Top, and, according to Kross, the 200 detached Alabamians would miss the Confederates’ subsequent attack.

The advance on the Union left by Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division began about 4 p.m. Almost immediately, Stoughton’s sharpshooters opened fire, followed quickly by Union artillery. Several Confederates later wrote of the devastation wreaked upon them by the Federal marksmen. “We advanced through a field about half a mile before we reached the…foot of the mountain,” wrote a member of the 5th Texas, “our men tumbling out of ranks at every step, knocked over by the enemy’s sharpshooters.”

Private John C. West of the 4th Texas, Company E, recalled in a letter written to his young son shortly after the battle: “When the command was given to charge[,] we moved forward as quickly as we could….Yankee sharpshooters were on the higher mountains, so as to have fairer shots at our officers. On we went yelling and whooping…minnie [sic] bullets and grape shot were as thick as hail, and we were compelled to get behind the rocks and trees to save ourselves.”

A soldier of the 4th Alabama recalled the chilling death of a comrade during the advance at the hands of a sharpshooter: “Taylor Darwin, Orderly Sergeant of Company I, stopped, quivered, and sank to the earth dead, a ball having passed through his brain.”

By nightfall July 2, Federal forces had withstood the repeated attacks on Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac’s vulnerable left flank, setting the stage for its victory the following day. Stoughton’s 2nd Sharpshooters regiment had disrupted the Confederates long enough to allow other Union units to fill what had been a glaring gap in the defenses along Little Round Top, most notably Colonel Strong Vincent’s 3rd Brigade in Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ 5th Corps and the 20th Maine Infantry under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain.

According to Colonel Berdan’s after-action report, 450 of his marksmen were engaged during the battle, expending 14,400 rounds of ammunition and suffering fewer than 30 total casualties.

Gettysburg was Berdan’s last time in the field with his elite unit. He was soon promoted to division command, only to resign his commission in early 1864. That December, the two regiments were merged into one force, but Berdan’s men never again had the sort of impact they’d had at Gettysburg, a prime example of what was possible when used in the role for which they had been created.

Nevertheless, Berdan’s Sharpshooters hold a distinguished honor in our nation’s history. Although military units with a similar purpose had been in use by armies in Europe, and American armies had adopted the use of isolated marksmen, Berdan’s was the first organized unit to wear camouflage and wield breechloading rifles in combat. Furthermore, their exploits as mobile marksmen—the “squirrel hunter of the war,” according to one of their own officers—set the stage for the eventual and critical military recognition of the scout-sniper in modern warfare.

Doug Wicklund is a senior curator at the NRA’s National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Va. Michael Williams is a freelance writer, and an NRA and Maryland State Police certified firearms instructor.

_____

Tools of the Trade

First designed by Christian Sharps in 1848, and slightly updated in 1863, the Model 159 Sharps rifle was rugged, accurate, and capable of firing 8-10 rounds per minute. The breechloading, single-shot rifle (converted post-Civil War to fire self-containing metallic cartridges) remained in production through the 1880s and became the preferred weapon of the Western Plains buffalo hunters (the 1874 Sharps, in several calibers, became renowned as “Old Reliable.”

Specs:

Manufacturer: Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company, Hartford, Conn.

Length: 47 inches (9 inches shorter than 1861 Springfield rifle-musket; Sharps carbine was 39 inches)

Weight: 9.5 pounds (0.5 pounds heavier than 1861 Springfield rifle-musket)

Caliber: .52 (1861 Springfield rifle-musket was .58-caliber)

Ammunition: “Paper” (waxed linen)-wrapped cartridges (lead bullet & 50 grains black powder)

Ignition: Percussion cap (or “Sharps pellets”—Sharps’ patented similar system)

Action: Lever-activated “falling block” (vertical sliding breechblock)

Rate of Fire: 8–10 rounds per minute (vs. muzzle loader 1861 Springfield rifle-musket’s 3 rpm)

Muzzle Velocity: 1,200 feet per second (slightly “supersonic” vs. 1861 Springfield rifle-musket’s 1,000 fps)

Sights: Barrel-mounted, open “ladder” sight

Effective Range: 500 yards (800–1,000 yards with skilled marksmen)

Bayonet: Standard triangular “socket” bayonet (none for carbine version)

Government Cost: $40 ($1,142 in today’s dollars)

Union Army Purchased 1861–65: 9,141 (80,512 carbine versions—meanwhile the U.S. government purchased 1 million Springfield rifle-muskets during that time). The $40 purchase price included for each weapon: one thong and one brush (for barrel cleaning—the Sharps had no ramrod); one wrench and screwdriver; one cartridge stick (as a form for hand-rolling paper-wrapped cartridges); one extra cone; and one extra primer spring. In addition, one ball-mold (for casting lead bullets) was provided for every five weapons. –Jerry Morelock

_____

A Tight Spot

Berdan’s Sharpshooters rushed into an open field ahead of the main assault on Stonewall Jackson’s troops at the Deep Cut during the Second Battle of Bull Run. Keeping up a steady fire, they managed to repel  Confederate skirmishers, but provoked Jackson’s men to fire back from the cover of a trace of an unfinished railroad and became pinned along a dry creek bed. George Albee of Company G, who was wounded during the action, returned to the spot after the war and placed a signboard on a tall cedar post to mark the location of his company during the attack. Although the pole has been replaced several times over the years since, a present sign occupies the same spot as the original at the Manassas National Battlefield Park.–Melissa A. Winn

Confederate skirmishers, but provoked Jackson’s men to fire back from the cover of a trace of an unfinished railroad and became pinned along a dry creek bed. George Albee of Company G, who was wounded during the action, returned to the spot after the war and placed a signboard on a tall cedar post to mark the location of his company during the attack. Although the pole has been replaced several times over the years since, a present sign occupies the same spot as the original at the Manassas National Battlefield Park.–Melissa A. Winn