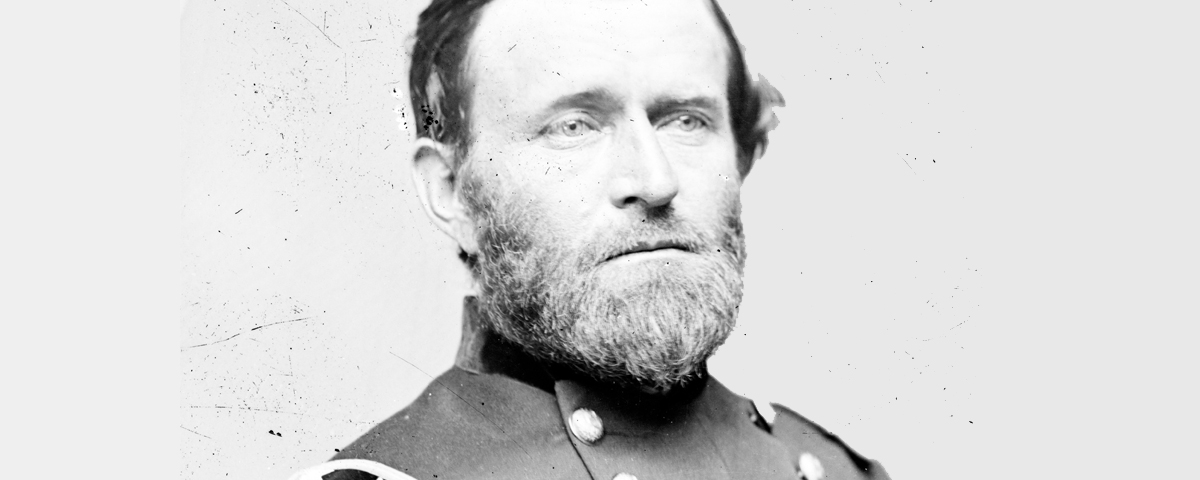

I GREW UP hating Ulysses S. Grant, if only because he was the one most responsible for vanquishing my childhood hero, Robert E. Lee. In our household, Lee came next to God and cleanliness, a paragon of soldierly form and virtue. To me Grant was just some grim romping stomping cigar-chomping lucky bum of a default Union general who came stumbling into history. But a later revelation shook that illusion and took me back to school on the whole subject.

I was reading Mark Twain, who referred to Grant as being “filled with sweetness, gentleness and goodness.” What? The old Butcher General of the Union Army? I could hardly have imagined those words existing in the same sentence as Ulysses Grant (or even Twain himself). My curiosity piqued, I spent months reading everything I could get my hands on about this figure. I was amazed at what I found.

Most historians agree on the basic facts on Grant and his times. Some of his biographers diverge, however, and they seem to share a certain frustration in explaining their enigmatic subject. They just couldn’t get Grant—his life, lineage, persona and vitae just didn’t add up to The Greatest Commander of the Greatest Army in the World.

The way I see it, Grant’s unlikely success in war can be attributed to a perfect storm of historic circumstances, fateful timing and personal attributes. His father remanded young Ulysses to West Point, which he barely tolerated, before he was immersed in the Mexican War, where his experiences imprinted on him the essence of combat, if mainly by keen observation. Later, as a civilian in the 1850s, he couldn’t seem to get anything together and failed at practically everything.

As the Civil War began and the relatively few available Army officers and ex-officers were choosing up sides, one of Grant’s peers—Confederate Richard S. Ewell—observed ominously: “There is one West Pointer…little known…whom I hope the northern people will not find out.” Otherwise, expectations of Grant were very low. He was given a small command, however, and soon got “found out,” proceeding to turn the tables on the South.

He figured out early how to win: Get in the enemy’s face and systematically grind him down with your superior resources. Grant proved to be focused, astute and resilient—but so were dozens of seemingly more qualified and forceful officers ahead of him. How was it that Grant, this middling colonel of Illinois Volunteers, could leapfrog over them all? The scene was set, destiny awaited and his amazing success emerged from the particular qualities of this most unlikely commander.

Centered character

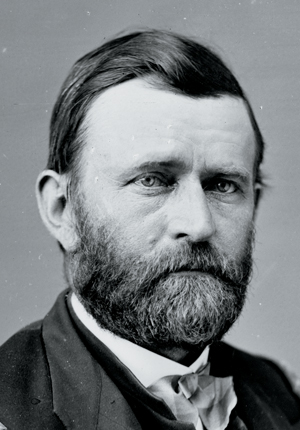

Grant was solid, stoic, low maintenance and utterly trustworthy. His forthright manner, stark honesty and good judgment won him increasing respect. Though he often was attacked and second-guessed, Grant proved to be practically beyond reproach.

The Grant personality was centered; no extreme or rough edges. He was shy, but not coy; pleasant and affable, but not gregarious; dignified, but not aloof; self-confident, but not sanctimonious; purposeful, but not ambitious; sensitive, but not sentimental. Grant was at once placid and a grand latent force.

He did his thing in the most unassuming way. Cool, quiet, humble and austere, Grant was hardly noticed in a room full of greater egos. “His face has three expressions: deep thought, extreme determination, and great calmness…” observed Theodore Lyman, a Union officer who had served under Maj. Gen. George Meade. “As calm as the cyclone’s core” was how writer Herman Melville put it. But when it was time for action, Grant “makes things git,” Abraham Lincoln said.

Grant was not an inspirational leader. Devoid of style and charisma, he did not capture the hearts and imaginations of his soldiers. He was endeared to them, however, by the uncanny power of his battlefield successes and by his total lack of condescension.

Whatever glory came to Grant was not sought. Good natured, tactful and polite, he was not burdened by vanity or ostentation. He was non-judgmental, tolerant and famously magnanimous. Grant had an amazing ability to endure criticism mainly by not reacting to it. He readily accepted blame and gave none himself.

Grant had no functional vices. He was occasionally intemperate, the more noticeable because of an inability to hold alcohol in his small frame, and an over-the-top cigar habit shortened his life. His weaknesses, he said, were “children and horses”: He was whimsical with the former and a skilled near-whisperer with the latter. Grant knew he had a war to win and was loath to let any personal fault or indulgence interfere.

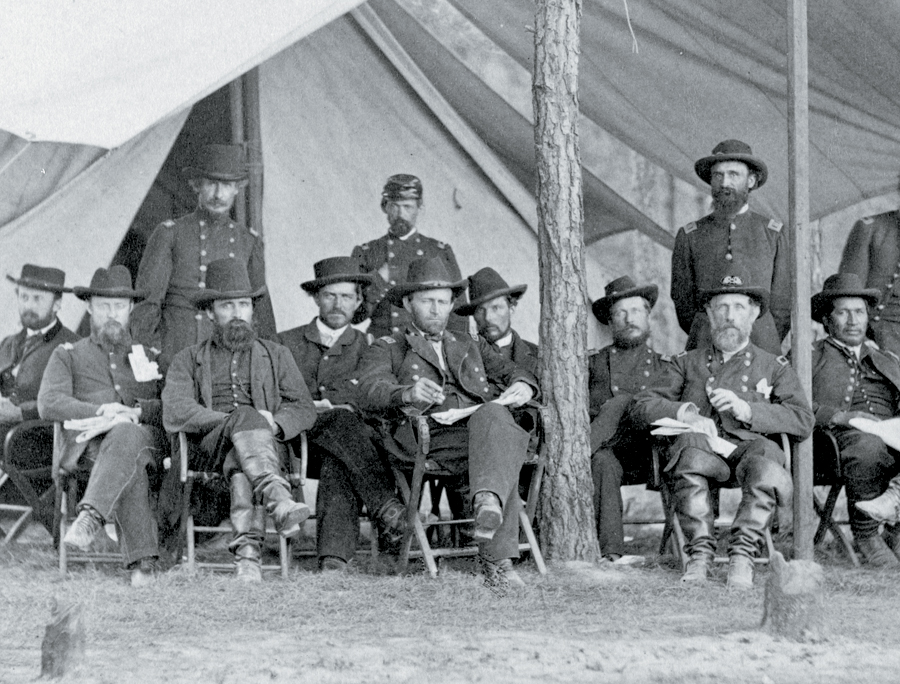

Command and control

There was no part of “when in command, command” that Grant didn’t understand. The military values of loyalty and unequivocal authority were well suited to his no-nonsense style. Although he was not one to take charge, when he was put in charge Grant was all about consistent orders, recognition, adaptation and momentum. Once he began racking up victories, Grant had little trouble getting others on his bandwagon.

Grant was not a debater. He was a good listener and respected his colleagues, but he kept his own counsel and made decisions in an esoteric fashion. Colonel James Rusling described Grant as a man who could “dare great things, hold on mightily, and toil terribly…he knew exactly what he wanted, and why, and when.”

President Lincoln loved him before they had even met. At last he had a real fighter—and one who was particularly easy to work with. Grant required no stroking, didn’t whine about his army’s deprivations and just went about the business of winning battles without bothering the commander in chief too much. Lincoln had been frustrated by having to be the general for all of Grant’s predecessors, who were too cautious, too concerned with glory or just incompetent. Grant and Lincoln combined formed one of the greatest command partnerships in history.

Grant’s greatest exercise in command was, perhaps, of himself. In war, he never let anything out that didn’t have to do with defeating the enemy. He was not without humor or emotions; he just had immense self-control. After the first disastrous day of gruesome combat at the Wilderness on May 5, 1864, Grant was heard sobbing in his tent. Next morning, his staff expected to retreat. Grant, however, turned his army to face the enemy.

Common sense

Although he was no genius, Grant was nevertheless a classic thinker. He was too pragmatic to be considered an intellectual and too colorless to be considered brilliant. But his mind was clear, sharp and intuitive, and he was quick on his feet. Grant also had a phenomenal memory and—some have said—a sixth sense in matters of time, place and terrain. Putting it all together, Grant gained a reputation for just being plain right most of the time, at least in war.

Above all else, Grant was a realist. After filtering for facts, he was driven to apply what he held to be true. Very little got through to or came out of him that wasn’t relevant, critical or certain. Anything having to do with pretense or illusion was stripped away. Factored out were any self-delusions, neuroses or irrational fears. The concept of denial was totally foreign to Grant.

He brought his uber-rationality and agility to bear with a determination that crushed any notions of a Southern victory. Grant could wring optimum utility out of most situations, using even the occasional failures simply to narrow down the remaining possibilities, focusing on the next move. “If his plan goes wrong he is never disconcerted but promptly devises a new one…” said William T. Sherman.

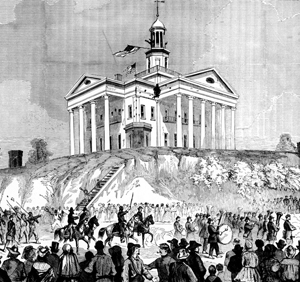

Grant was not afraid to take calculated risks, a number of which resulted in his huge victory at Vicksburg—after which Lincoln conceded, “You were right, and I was wrong.”

Frank communication

If Ulysses Grant had a defining trait, it was his ability to communicate and get his point across. The manner of his speech and writing, without any distinctive style, reflected his character: direct, composed, reserved and utterly clear. His words were few, but of great substance: honest, credible and reassuring. He was a master of syntax and his words were well chosen from an effectual but not overbearing vocabulary. Some occasional trouble with spelling comes off as endearing in sentences that are otherwise lucid.

The most effective tactical weapons in Grant’s arsenal were his own words. He led from the pen with short, comprehensible battle orders. “There is one striking feature about his orders; no matter how hurriedly he may write them on the field, no one ever has the slightest doubt as to their meaning,” observed Horace Porter, Meade’s chief of staff. The recipient could instantly “get it,” allowing Grant’s armies to be fast afoot. The series of orders that Grant gave in his career made for one of the greatest success stories in military history.

With the publication of his hugely popular memoirs, which he completed in 1885 as he was dying of cancer, Ulysses Grant became the most prolific top military memoirist of all time. In both substance and form the memoir was all Grant, with customary candor, accuracy and readability. Today the work still ranks as world-class literature in its own right.

Nurtured confidence

Facing the enemy in his first command, Grant overcame doubts and learned to allay fear. From the moment of his first victory he gained growing confidence in himself and his nation’s cause. Given the means, Grant believed he could roll up the Confederates and win the whole war.

Success bred more success for Union armies under Grant. Wherever he went, he saw the situation, took charge, got results and exploited his weakened enemy. Grant’s optimism and “simple faith in success” were infectious. Momentum built, and his soldiers liked being with a winner. And they didn’t mind that their leader disdained the drama of it all. The Union Army was finally galvanized, and imminent victory gave confidence even to many of Grant’s less talented officers. Joshua Chamberlain reflected that Grant had “the rare faculty of controlling his superiors as well as his subordinates.”

His most critical vote of confidence came from Lincoln himself, whose trust in Grant was “marrow deep.” After Vicksburg surrendered to Grant in July 1863, Lincoln declared, “Grant is my man, and I am his, for the rest of the war.” After the war, the nation had enough confidence in Grant to elect him president twice—without his actively campaigning for himself. Imagine that now.

Because he saw himself as an enlightened commoner, Grant’s success never really went to his head. In his view, if he could be confident in himself, he could be confident in others, too. Tragically, this trusting nature became a weakness in Grant, and his postwar years were marked by misplaced trust in others coming to unhappy effect—from corruption by subordinates during his presidency to bad business associations afterward. Off the battlefield, Grant’s vision was less clear and his ability to control events compromised. But his intentions were good and he never lost the affection of his constituents.

Cumulative courage

Whenever it was time to do the right thing, Ulysses Grant was dauntless. Faced with hard choices after a tough battle, Grant could be counted on to press the enemy. “Ulysses don’t scare worth a damn!” exulted one Wisconsin soldier after watching Grant write a dispatch as a shell exploded directly in front of him. His unflinching bravery in combat was unquestionable. There would sit Grant scribbling orders, with bullets whizzing by, directing his army into harm’s way somewhere else, driving the enemy. Sometimes injured, usually from moving around so rapidly on horseback, Grant would endure with the toughest of his men the pains and privations of an army in the field.

Moral courage is said to manifest in a person willing himself to step outside of his natural bounds and into danger for some higher purpose than security or even survival. It was unnatural for shy, live-and-let-live Ulysses Grant to ask others for such sacrifice, but that’s what he had to do. Achieving peace would ultimately require terrible bloodshed and social wreckage. It fell to Grant to get it over with as quickly as possible, not because he relished the job, but because he was the best-proven warrior in the land.

Grant’s most severe test of courage came long after the war, during the last year of his life. Rendered destitute after being swindled by a business partner and dying of throat cancer, Grant was utterly down and out. The pain was bad enough, but the impact of his new ignominy on his family was perhaps worse. Then Mark Twain came along with a propitious offer: Spend your last days writing those long-deferred memoirs. The volumes would sell stupendously well, lifting the Grant family out of poverty and restoring his honor.

But first Grant had to fight through the pain and stay lucid enough to write, waving off the intermittent drugs that brought both relief and debility. No greater struggle did he ever endure than keeping himself alive long enough to finish his heroic work.

Conviction to the cause

As the war progressed, Grant became a man on a mission, quietly but forcibly crusading for unity and freedom. He had found success in war by constantly leaning forward with his agenda, controlling the battlefield and one-upping the opposing general practically every time. With Lincoln, he enabled one of the most significant societal transformations of all time. None of it might have happened, however, had it not been for the core values and personal constitution of Ulysses S. Grant.

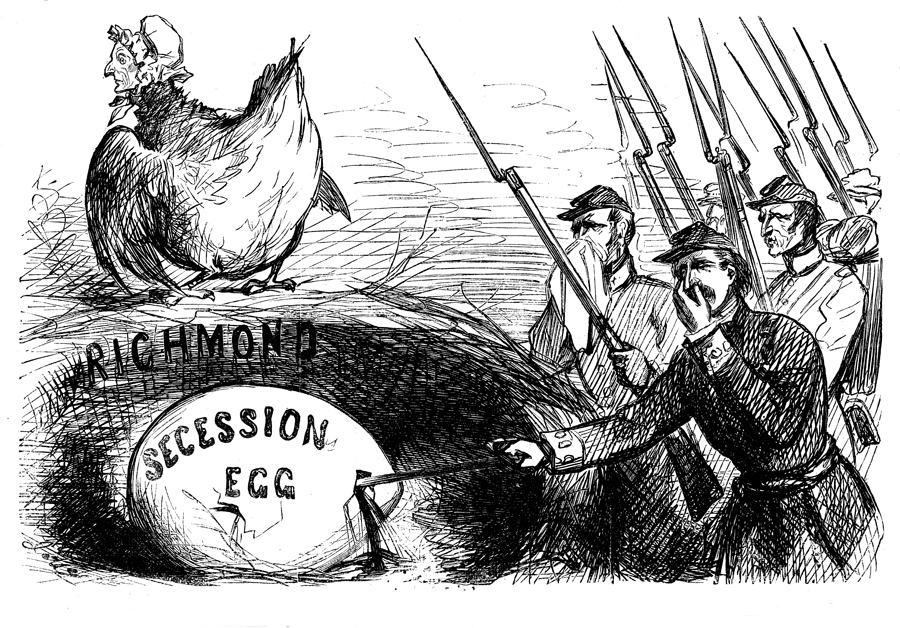

Nobody would figure that the South’s secession would so rile Grant that he would make it his life’s purpose to put down the rebellion. He felt no hatred toward Southerners (indeed few have ever had to fight against so many former friends and colleagues), but he was utterly contemptuous of their cause—“the worst for which a people ever fought,” he observed. Though not passionate about soldiering, Grant would use his position and ability to fight hard as a means to ending slavery and restoring the Union.

Before the war, Grant had been a serious underachiever and was rarely outspoken. Privately, however, he maintained a strong patriotic ethos. A divided America, he believed, only weakened all. In his opinion, unity of purpose and equality were essential, and the new Confederacy threatened them both. “No stouter foe of anarchy in every form ever lived within our borders,” Theodore Roosevelt later observed.

Worse still was the institution of slavery. The more Grant reflected on this abomination, the more incensed he became. Grant could never abide cruelty, abuse or injustice, and slavery was deeply offensive to his egalitarian soul. He became a champion for the oppressed, and later, as president, he was a great friend to African Americans and Native Americans alike.

Despite being made a hero by the Civil War, Grant just wanted unity and order. “Let us have peace,” he urged when he was nominated for president in 1868. He and Lincoln had used the terrible tool of war to drive the nation to its moral senses, and from Appomattox forward nobody did more than Grant to reconcile the societies of the North and South.

Close companions

Finally, two people close to Grant figured significantly in his success. His marriage was a model of love and support, and the many letters from the field to his wife Julia are a chronicle of the war and the inner Grant. Also influential was his adjutant John Rawlins, his best friend and alter ego, in whom Grant had wisely invested his conscience, and to whom he would listen. “I always disliked hearing anyone swear, except Rawlins,” he once said.

This was Grant’s secret weapon: a studiously low profile masking his own good character, ability and drive. He was easy to underestimate. Friends were amazed and foes were bewildered by his unique success. How could this peaceful man of such soft disposition also be so tenacious and steely? Grant was hardly tops in any one skill or virtue, but taking the sum of his parts he was the most complete general in the Army. Once the character of the man is understood it should not be so surprising that he would thrive in a conflict like the Civil War.

My opposing idols from North and South can now be reconciled. My great affinity for Robert E. Lee is undiminished, though Ulysses S. Grant emerges a new hero. Grant will never be an icon like Washington or Lee, though he warrants greater recognition, and his feats are far more instructive on what it takes to succeed.

Jim Stickney of Asheville, N.C., is a reconstructed Southerner and lifelong student of the Civil War.

This article was originally published in the January 2016 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.