Jakob Reimer mastered dodging the past—and passing as an ordinary U.S. citizen.

ON A FRIGID WINTER DAY in 1994, Jakob Reimer stepped onto the front porch of his rambling frame house along the shoreline of New York’s Lake Carmel, sized up the stranger who had come to talk about the war, and abruptly declared, “I am the most hated person in America.”

Reimer’s Eastern European accent had softened over the years and, in bedroom slippers and slacks, with tufts of silver hair combed over his ears, he looked every bit the ordinary American. At 76, he had long ago eased into a quiet retirement in the lakeside hamlet of 8,000, 60 miles north of Manhattan, where slower days waited on a spit of a beach and in the faded blue dinghies that bobbed along the water.

But now a visitor was asking pointed questions about Reimer’s involvement in some of World War II’s darkest moments—a deadly stretch of deployments in German-occupied Poland. Two years earlier, federal prosecutors in Washington, D.C., had accused him of helping to train and lead members of a brutal SS killing force behind the most skillful and comprehensive mass murder operation of the Holocaust.

The details had been buried for decades in the archives of Communist countries, but in a dusty basement in Prague in 1990, two American historians with a U.S. Department of Justice Nazi-hunting unit, Peter Black and Elizabeth “Barry” White, had unearthed an SS roster from the war years. It contained the names of more than 700 men—Reimer among them—who had been sent to an obscure training camp in the Polish village of Trawniki, an SS school for mass murder where some 5,000 recruits in all were armed, empowered, and deployed on deadly missions across occupied Poland.

The so-called “Trawniki men” became a ruthless workforce: a small army of collaborators who helped the Germans murder 1.7 million Jews, along with Roma, Poles, and Soviet POWs, in fewer than 20 months. Black, who would go on to become the world’s foremost expert on the training camp, called the recruits “foot soldiers of the Final Solution.”

Jakob Reimer, federal prosecutors alleged, had been a trusted Trawniki leader, one of the camp’s most steadfast workers. Reimer had denied the government’s allegations, insisting that he had never taken part in the persecution of Jews. But he had gone on to confess under questioning to shooting at a prisoner during a massacre deep in the woods outside the camp.

“I just say that I had to make one effort at least while the German was looking at me,” Reimer had told prosecutors two years earlier. “I shot at the direction…. I couldn’t very well just stand there. I had to make an effort or something.”

More than 40 years after Reimer had slipped into the United States alongside thousands of war refugees from Europe, the Justice Department was pressing to strip him of his U.S. citizenship and remove him from the country. It was an intolerable thought to Reimer, who had an American wife and American sons, a church, a Social Security card, a respectable end to a career running a potato chip franchise in Brooklyn.

Pacing his front porch, he studied New York magazine journalist Jeffrey Goldberg, who was writing a story about the government’s pending denaturalization case. All his life, Reimer had survived on his wits and easygoing manner, staying one step ahead of fate even during the most trying times. Under the unflinching glare of the Justice Department and history itself, he was quite certain that his future depended on how he answered for his past. He looked at Goldberg.

“They have the wrong man. I did not do anything to the Jewish people.”

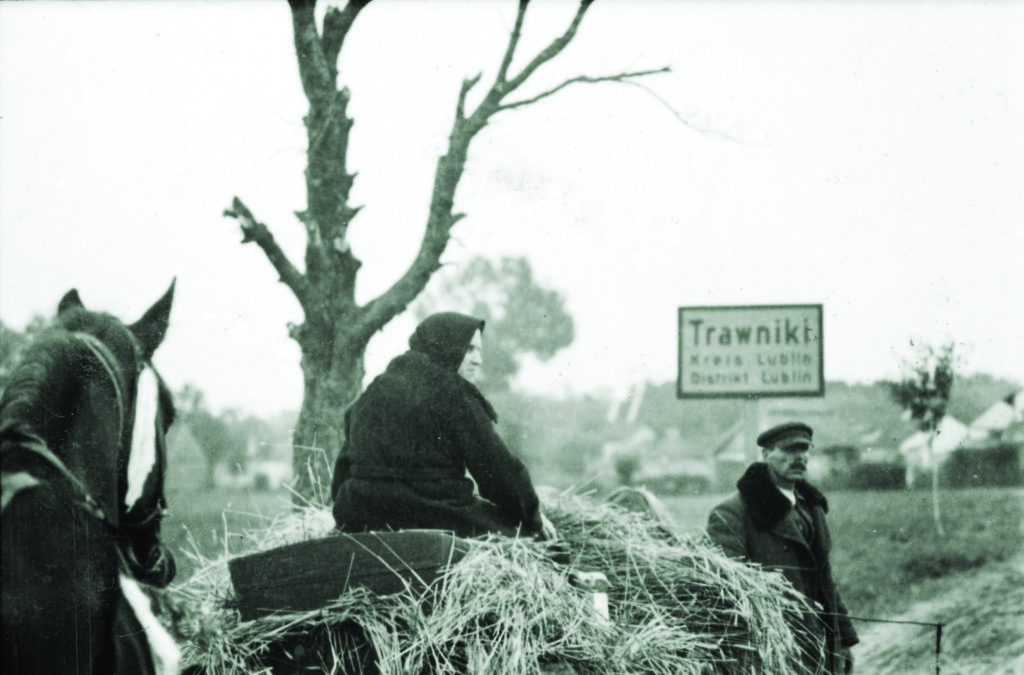

IF IT WEREN’T FOR a sugar refinery and a railway station, there may never have been a thriving Polish settlement in the village of Trawniki. Traders and craftsmen migrated to the area at the end of the 19th century, turning the sprawling countryside about 130 miles southeast of Warsaw into a small village, with thatched-roof houses and farms that in the summer months grew bright-yellow canola flowers.

One hundred Jewish families from a nearby congregation had settled on land near the refinery and, even after the plant closed a few decades before the war, the modest village maintained a tiny industrial core, linked to the rest of Poland through rail lines that snaked across the country in every direction.

An ideal place to train and deploy a makeshift army.

In late summer 1941, Jakob Reimer, a then 22-year-old ethnic German born in Ukraine, arrived in Trawniki in a convoy of captured Soviet soldiers, altogether surprised that he was still alive. The Germans had overrun his platoon in Minsk, and Reimer—a Red Army officer with the 447th Soviet Infantry Regiment—had been taken to Stalag 307 in eastern Poland.

If the Germans discovered his rank, Reimer knew there would be no mercy. Hitler had instructed the high command of German armed forces to summarily shoot officers and Communist officials at the time of capture. Word of the order had spread among Red Army soldiers. Reimer had been sure to destroy his papers, but it seemed only a matter of time before the Germans identified him as an artillery lieutenant who had commanded a platoon of Soviet soldiers.

But he had been recruited, not killed—a startling twist of fate.

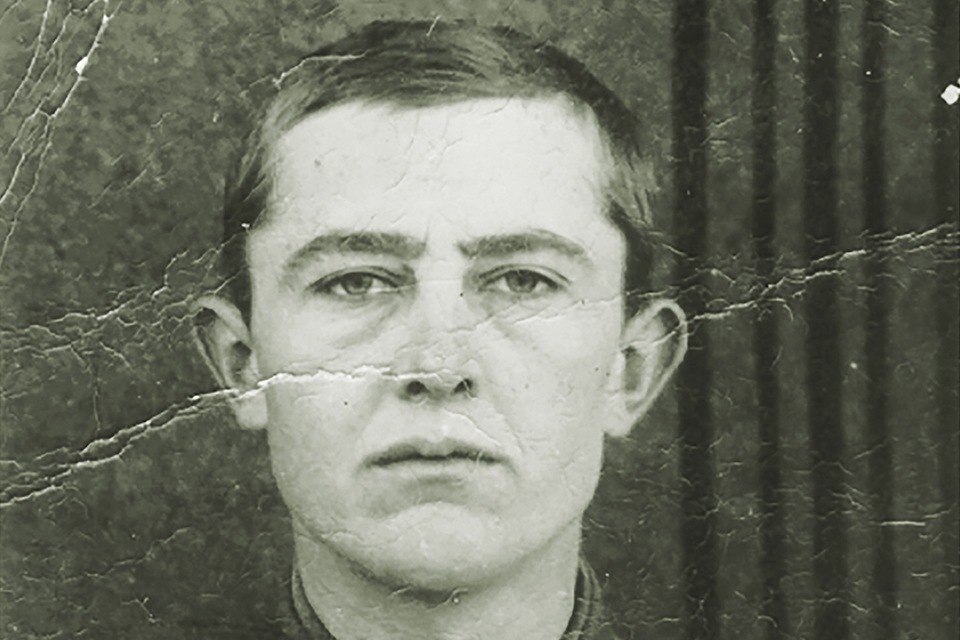

And now he found himself in what appeared to be an SS training camp, posing for a service photo as a newly dubbed auxiliary police guard. Black hair, gray eyes, the lines of his mouth drawn into something of a grimace.

Did he ever belong to the Communist Party? Reimer had said no. Was he racially pure? Did he have Jewish ancestors? Reimer knew quite well that Germans routinely shot Jewish soldiers of the Red Army. No, he’d said again.

Reimer was fingerprinted and offered a hand-me-down Polish army uniform that had been dyed black. He was also given an identification number that would follow him throughout his career as a Trawniki man: 865.

Reimer followed the other recruits to a barn where they would be housed, in the shadow of a watchtower. Most of the men were like Reimer—Soviet POWs who had been recruited to serve the SS. They would undergo rudimentary training: military drills and lessons on how to use the weapons they would soon be issued. They would be taught German marching songs and attend lectures about the superiority of the German race. If they served with honor, they would receive food, beds, and spending money of one half a Reichsmark per day.

For that, Reimer was grateful.

He had been born in 1918 in a farm village in Soviet Ukraine, the sixth of seven children. His father had come from Holland, but his mother’s family was among the Volksdeutsche who had migrated from Germany to the Ukrainian countryside under the rule of Tsarina Catherine the Great in the 18th century. Drawn by the prospect of work in agriculture and of exemptions from German military service, thousands had settled in the region.

Reimer’s village, along a half-mile stretch of dirt road, was filled with families from northwestern Germany that spoke a dialect known as “Plattdeutsch.” On a plot of land lined with rose bushes and fruit trees, Reimer’s father had grown wheat and taken it to the windmills to grind into flour. The family attended a small church in the village, and Reimer went to school with other Volksdeutsche children.

In the 1930s, famine swept the Soviet Union—instigated by Joseph Stalin to impose forced collectivization—and Soviet authorities started confiscating Volksdeutsche farms and holdings. Reimer’s family lost everything: the land, pigs, and horses. Reimer’s father was sent to a labor camp and his older brother to Siberia. Reimer, his mother, and younger brother fled to a Mennonite settlement in the Caucasus. Reimer, a skilled horse trainer and jockey, found work at a nearby track, learning Russian and quickly impressing his Soviet supervisors. Keenly aware of the repression his family suffered, he enrolled in a Russian school, a sure way to survive under Stalin’s rule. He planned to become a librarian. But at the start of the war in 1939, he was drafted into the Red Army. Well-schooled and eager to display his loyalties to the Soviet regime, he was made an officer and given his own platoon of soldiers.

In the barn at the Trawniki training camp—hundreds of miles from home and wearing the uniform of his enemy—Reimer studied the eclectic group of recruits: fellow ethnic Germans, Lithuanians, Latvians, Ukrainians, the occasional Pole. Most were young, like Reimer, still in their early 20s. They were filthy and starving, but Reimer knew they were among the lucky ones.

The Germans, busy fighting on the Soviet front, were desperate for manpower. SS chief Heinrich Himmler planned to eventually Germanize the occupied East, a strategic and economic stronghold for the Reich, with lush farmland that Nazi leaders intended to turn over to ethnic German settlers living in Yugoslavia, Hungary, Romania, and the Soviet Union. Under the command of the SS leader for occupied Poland’s Lublin District, the SS had pulled men from Soviet POW camps: German speakers, skilled workers, and those who looked reasonably healthy. Reimer and the other recruits had been offered food and straw for bedding, a much-welcome gesture after imprisonment behind barbed wire.

“We lived like animals,” Reimer would say later to federal investigators. “Now there was a building; you had a bath.”

To survive at Trawniki, Reimer would have to put his Soviet past behind him and start again—this time as a trusted collaborator of the SS.

IN MARCH 1942, seven months after Jakob Reimer arrived at Trawniki, the entire camp prepared to head north. The first major deployment would turn into an assignment spanning several weeks in the nearby city of Lublin and its Jewish ghetto, crowded with tens of thousands of people. By then Reimer had leveraged his German-language skills to great advantage. He had been promoted to platoon leader, tasked with training and leading Trawniki recruits.

Reimer and hundreds of Trawniki men—almost all of those recruited since the establishment of the training camp—arrived in Lublin after nightfall and, in the still-dark early-morning hours, fanned out along the perimeter of the ghetto, rifles cocked and ready. They lighted the streetlamps and summoned surprised families outside. Some Trawniki men panicked, prompting an early round of bloodshed. Gunshots rang out into the night air. Rifle butts cracked against bone. Whips snapped against flesh. Years later, witnesses would recount how the men of Trawniki had tossed children out the windows of apartment buildings and shot the elderly and sick on the spot, how afterward bodies lay on cobblestone streets.

The ghetto was one of the largest in Poland, packed with Jews from Lublin as well as thousands who had been sent on trains from surrounding towns. For weeks, the Trawniki men, assisted by local police forces, took as many as 1,500 people a day to waiting boxcars two miles away. They were deported to Belzec in southeastern Poland, an SS-run center built solely for death, with double-walled gas chambers only a few hundred feet from the train platform.

Some SS and Trawniki men went to the Jewish hospital in Lublin, where they loaded 200 patients onto trucks, drove them outside the city, and shot them. They also murdered residents of a nursing home and children from a Jewish orphanage.

Early one morning that spring, a company of Trawniki men climbed onto SS trucks and headed north, winding some 10 miles along country roads to the entrance of the Krępiec Forest, hushed and still. Another truck pulled up, this one filled with several dozen Jewish prisoners from what was left of the ghetto, a terrified mass of men, women, and children. The prisoners were told to drop their belongings on the ground by the side of the highway. The Trawniki men drove the prisoners deep into the woods, down a trail with twisted branches and crushed leaves.

There was a clearing about 1,000 yards away. Some of the Jewish men had been told they would be put to work in the woods, but they found only a large, jagged hole in the ground. Women started to wail as the Trawniki men used their rifle butts to prod the prisoners closer to the pit. Gunfire erupted. In seconds, the bodies were motionless, a mass of tangled limbs. More transports showed up, each truck filled with 50 people.

The shootings lasted well into the night.

AS EFFICIENT MASS MURDER increasingly expanded under German rule, Reimer was deployed to the southern Polish city of Częstochowa on the Warta River northwest of Kraków. In September 1942 on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, German police, reinforced by Trawniki men, began ordering the city’s 40,000 Jews to gather their hand luggage and assemble on the streets. The elderly and frail were shot on the spot; the rest, made to remove their shoes to deter the possibility of escape, were forced onto 58 train cars bound for the killing center Treblinka.

During the mission Reimer had positioned guards in the ghetto and coordinated with the Germans and local authorities; for his success, he was promoted to Zugwachmann, a guard staff sergeant.

In April 1943, Reimer arrived in Warsaw for his third deployment. The largest ghetto in German-occupied Poland had once confined more than 400,000 people in less than two square miles of space. By the time Reimer showed up, during the Jewish holiday of Passover, the SS and police had killed or deported to Treblinka most of the ghetto’s residents. About 60,000 Jews were left. During a previous attempt to remove Jews, the Germans had met resistance. They expected more now.

Reimer reported to the German security police just inside the ghetto. Three hundred and fifty Trawniki men were already there, ready to help suppress any Jewish resistance. The Germans had brought in combat engineers, demolition experts, a squad of flamethrower specialists, tanks, armored carriers, machine guns, and explosives. Even the Luftwaffe stood ready.

They expected to round up thousands of people, but many of the ghetto’s remaining inhabitants had fled to a labyrinth of dugouts, bunkers, cellars, and passageways dug deep beneath the earth, some equipped with cots and food supplies meant to last months. Resistance fighters took aim from sniper holes; several dozen mounted a German truck and drove off. Jewish women fired pistols with both hands and tossed grenades that they had concealed in their undergarments.

It was the start of a fierce, bloody operation, and at nightfall, Reimer and the Trawniki men, armed with rifles, bayonets, and ammunition pouches, retreated to a bunker in a schoolhouse a half-mile west of the ghetto.

The Germans decided to burn the ghetto, street by street. Soon, flames charred apartment buildings, warehouses, stores, and workshops. German forces threw tear-gas bombs into sewers and poison gas into dugouts and bunkers. Those still in hiding scrambled out into the light, hands on their heads, dirt on their faces. A first glimpse of black leather boots. A final surrender into the eye of a cocked machine gun.

The Warsaw ghetto uprising ended three weeks later, with all but eight buildings leveled, more than 7,000 Jews killed, 7,000 deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka, and 42,000 sent to Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp outside Lublin or to forced-labor camps in the villages of Trawniki and Poniatowa. The German commander in charge of the Warsaw operation praised his patchwork army, including the Trawniki men, for “pluck, courage and devotion.” Assured the commander: “We will never forget them.”

Reimer earned a two-week paid vacation. He went to find his sister in the Ukrainian countryside in July 1943 before making his way back to Trawniki. Only months after his return, the Germans would shoot nearly every Jewish prisoner then being held at Trawniki and two nearby camps in a massacre known as Operation Harvest Festival.

IN THE SPRING OF 1945, as Soviet forces pushed west, Reimer’s commanders issued one final order: burn your papers and run.

Reimer ditched his Trawniki uniform, donned civilian clothes, and made his way toward Munich. With three successful deployments, Reimer’s service at Trawniki had earned him service medals and citizenship in Nazi Germany. Now, his life depended on his ability to keep his identity a secret. If he were found out, the Soviets would call him a traitor; the Americans, a Nazi collaborator. To survive, he would have to put his past behind him, find a way to recast himself all over again.

He decided to masquerade as a war refugee and again make use of his German-language skills. He got a job with the U.S. Army’s 26th Station Hospital, chauffeuring GIs to movies and frequenting dance halls at night. Still, it would be best—safest—if he could start again. Ships with thousands of refugees were leaving Germany, bound for America. In passing the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, the U.S. Congress had offered to provide refuge to hundreds of thousands of Europeans, particularly those fleeing Communism.

“I was determined to get out of there,” Reimer would tell prosecutors years later. “Quite frankly, I didn’t have my hope up.”

Reimer filled out an immigration application, careful to say that he had worked only as an interpreter for the German army during the war. He likely would have received quick approval, but U.S. authorities flagged the case after learning that Nazi Germany had granted him citizenship in 1944. The U.S. Army Counterintelligence Corps launched an investigation. What was Trawniki? Reimer had noted his service at the camp on his German citizenship application. He told the Americans that he had been only a guard-soldier and interpreter, and later a paymaster in the Trawniki administration. It had been mundane work for the Germans, he said, bureaucratic in nature.

Luckily for Reimer, the U.S. State Department knew little about the camp. In June 1952, the transport ship USS General M. L. Hersey left Bremerhaven, West Germany, and crossed the choppy waters of the Atlantic. It eased into the harbor in New York City, where David Garroway was anchoring the Today show and Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra were on a winning streak that would take the Yankees to their fourth consecutive World Series.

Hundreds of European refugees spilled out onto the streets of the city. One of them was Jakob Reimer, Trawniki recruit 865.

ON THE FRONT PORCH of his house in Lake Carmel in 1994, Reimer was frustrated. Turning to journalist Jeffrey Goldberg, Reimer insisted that he had done nothing wrong. He had been a supply sergeant at Trawniki—nothing more—forced into service by the SS and kept in the dark about the fate of the Jews. From his porch, Reimer started to shout. “Did World War II happen? Yes. Did I do what they said I did? No. I’m at peace with myself.”

But federal prosecutors had more than 80 German documents and 132 statements from victims, witnesses, and Nazi perpetrators. The work of Peter Black and other historians, and the prosecutors at the Office of Special Investigations, had laid bare Reimer’s stretch of deployments and the scope of the Trawniki training camp itself.

Four years after Reimer’s interview in Lake Carmel, the Justice Department presented its case against him in the Southern District Court of New York. Then 79, Reimer insisted he was innocent. In a courtroom packed with lawyers, journalists, and Holocaust survivors, he described himself as a starving prisoner of war and an unwitting Nazi recruit.

“Have you ever persecuted any Jewish people?” Reimer’s lawyer asked.

“No, I haven’t.”

“Have you ever hated any group of people—African Americans or Gypsies or Jews or

anybody?”

“No way, no,” Reimer answered. “You are supposed to love all the people.”

Four years after the hearing, in September 2002, the judge found that Reimer had “logistically supported” the SS during the most violent months of the Holocaust. He was stripped of his U.S. citizenship and given 30 days to turn in his passport.

In New York, U.S. Attorney James Comey, who would go on to become the seventh director of the FBI, told the New York Times, “Reimer’s presence in the United States is an affront to all those killed in the Holocaust.”

Though Reimer’s past and the history of the Trawniki training camp had officially become part of the public record, pieced together by a small group of American Nazi hunters, Reimer managed to stay a step ahead of fate. Before the federal government could find a country willing to take him, he died in Pennsylvania in 2005. ✯

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of World War II.