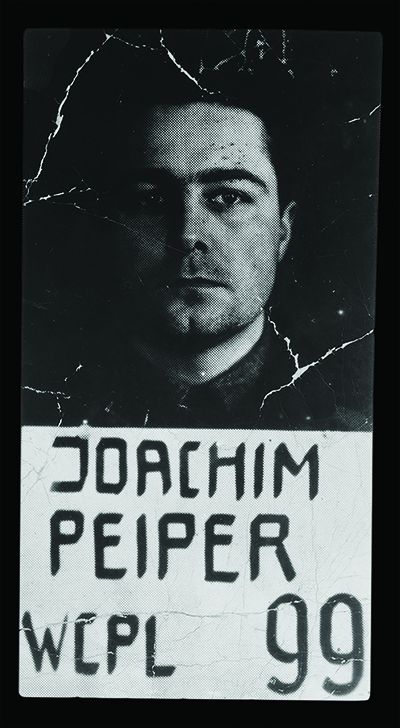

FOR THE AMERICAN SOLDIERS who had suffered and bled in the fight against Nazi Germany, it was a day they never wanted to see. At 2 p.m. on December 22, 1956, former SS colonel Joachim Peiper, whom the Associated Press called the GIs’ “personal No. 1 war criminal,” walked out of Landsberg prison in West Germany a free man.

A decade before, Peiper had been sentenced to be hanged for orchestrating the slaughter of 84 American prisoners near the Belgian village of Malmedy during the Battle of the Bulge. Since then, however, U.S. Army missteps, the Cold War, and international political intrigue had converged in unexpected ways to help Peiper dodge the hangman and gain his freedom.

THE MASSACRE that had set these events in motion occurred in another December—12 years before Peiper strode out of prison.

In December 1944, Germany planned a surprise offensive to win a war that already seemed lost: a lightning thrust through the Ardennes to split the British and American armies and seize the Allied supply port of Antwerp. Americans would call it the Battle of the Bulge. Peiper’s command, the 1st SS Panzer Regiment, was assigned to lead the Sixth Panzer Army’s assault and capture the bridges over Belgium’s Meuse River.

At 29, Peiper was the Waffen SS’s youngest regimental commander. From 1938 to 1941, he had served as an aide to SS chief Heinrich Himmler. Transferred to the Eastern Front in 1941, Peiper had earned fame as a daring combat commander, and his men had gained notoriety for their brutality.

On December 15, 1944, Peiper briefed his officers on the upcoming attack into Belgium. He relayed an order from Sixth Panzer Army headquarters, signed by its commanding officer, SS general Josef “Sepp” Dietrich. The order instructed German troops to fight “with no regard for Allied prisoners of war who will have to be shot if the situation makes it necessary and compels it.” Peiper instructed his men to “fight in the same manner as we did in Russia…. The certain rules which have applied in the West until now will be omitted.” Speed was crucial, he stressed, and they shouldn’t “pay any attention to unimportant enemy goals nor booty nor prisoners of war.”

Before dawn on December 16, the Germans launched their offensive on an 80-mile front. Although poor roads slowed Peiper’s drive and he had to push his men for increased speed, the assault came out of the blue for the Americans and confusion reigned as many outfits were overrun or retreated.

At 1 p.m. the next day, Battery B of the U.S. Ninth Army’s 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion was making a 50-mile road march south from Schevenhütte, Germany, to reinforce U.S. First Army troops in Belgium when a superior force of German tanks and grenadiers brought them to a halt at a remote crossroads two miles south of Malmedy. Riding in 26 jeeps and trucks, the Americans were lightly armed, mostly with carbines, and knew they had no choice but to surrender. The Germans—Peiper’s men—herded the prisoners together and marched them toward an open field near the crossroads. “Young guys they were mostly, but big and arrogant as hell,” Sergeant Kenneth Ahrens recalled of the SS men.

The Germans gathered the 100-plus prisoners and lined them up in the field. The GIs stood 20 abreast and several rows deep, unarmed and with their hands raised. Peiper was not present; he had advanced past the crossroads minutes earlier. Two half-tracks pulled up to the front corners of the field, and another armored vehicle parked between them. A German soldier in the middle vehicle fired two pistol shots, and two Americans fell. As if on cue, the machine guns on the flanks opened up, raking the field from left to right. GIs fell to the ground, some dead, some wounded, and some trying to escape the murderous fire, as agonized screams pierced the air.

After about three minutes, the machine gun fire stopped, but Peiper’s men weren’t done. They walked through the field, finishing off with pistol shots or rifle butts anyone who showed signs of life. “They were having a hell of a good time laughing and joking while the [American] boys were praying,” Ahrens said. Those still alive played dead and waited. As German vehicles passed the field, they fired again at the prone Americans. Private Homer D. Ford heard the thud of bullets hitting the men and cries of pain.

After about 90 minutes lying motionless, those still alive knew it was now or never. “Let’s go,” one shouted, and whoever could do so ran or stumbled from the field. Some were shot by Germans still at the crossroads. Others sought shelter in a nearby café, but the SS men set the building on fire and killed the GIs as they fled the flames. Thirty-five GIs, however, got away and reached American lines, bringing the first reports of the massacre.

The news spread quickly among American troops. Stars and Stripes, the GI newspaper, told of “muddy, shivering survivors, weeping with rage” as they described how “German tank men tried with machine guns to massacre 150 American prisoners standing in an open field.” Enraged soldiers wanted revenge. “If that is the way they want to fight—then that’s all right with us. But let’s us fight that way, too,” Private Herschel Nolan told a reporter. One U.S. infantry regiment even issued an order of dubious legality that “no SS troops or paratroopers will be taken prisoner but will be shot on sight.”

The Malmedy massacre was a shock to both GIs in the field and Americans at home because the Germans typically took prisoners when fighting on the Western Front. Peiper’s men were an exception. The U.S. Army blamed them for murdering more than 360 American prisoners and over 100 unarmed Belgian civilians during the Ardennes offensive—the only organized atrocities of that campaign. Under both the 1929 Geneva Convention and the 1907 Hague Convention, the killing of prisoners constituted a war crime.

American troops did not retake the fatal crossroads until a month later, on January 14, 1945. Battery B’s abandoned vehicles still littered the roadway, and the bodies of the prisoners lay in the field as they had fallen, frozen solid by the cold Belgian winter and covered with snow. Investigators placed a numbered placard on each body for identification, and army doctors conducted autopsies. Nearly all of the 84 victims had been killed by small-arms fire. Twenty had been slain execution-style, shot in the head at such close range that their bodies bore powder burns; three had their skulls caved in by rifle butts. Several had their eyeballs gouged out by a sharp object—probably while they were still alive, an army doctor concluded. From questioning German prisoners, the army knew the massacre was the work of Peiper’s 1st SS Panzer Regiment. Still, identification of the shooters would have to await the end of the war.

BY THE SUMMER OF 1945, with the war in Europe over, the army War Crimes Branch shifted into high gear. More than 500 SS soldiers suspected of war crimes, including Peiper and his men, were rounded up from scattered prison camps and hospitals throughout Europe and the United States and brought to an Allied internment camp in Zuffenhausen, Germany.

Any hope of building an easy case against the men of the 1st SS Panzer Regiment dissolved in October 1945, however, when 15 Malmedy survivors viewed Peiper’s men but couldn’t identify any shooters. For a successful prosecution, the War Crimes Branch realized, “the Germans would have to convict themselves” by confessing and implicating their comrades. With hard-bitten SS veterans, that would be no easy task, as the first interviews showed. Each German told a convenient story: he had passed the crossroads just before or just after the massacre. They said the order to shoot prisoners had come from an officer known to have been killed in the war’s closing days.

In December 1945, the prisoners were moved to a civilian jail in the southern German town of Schwäbisch Hall for interrogation. Twelve investigators were assigned to question the prisoners. Few, though, had experience with criminal cases; the rapid postwar demobilization meant experienced personnel were in short supply, and “we were obliged to use the people we had,” said Colonel Claude B. Mickelwaite, commander of the War Crimes Branch. Some of the investigators were ’39ers—army slang for men who had fled Europe shortly before the war.

One such man was Lieutenant William R. Perl. Born in Prague, Perl, 39, had practiced law in Vienna. When the Nazis began disbarring Jewish lawyers, he emigrated to the United States. Before leaving, Perl had helped several thousand Jews escape to Palestine. He had a personal reason to despise the Nazis: they had held his wife for two years in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Perl was an “eager beaver,” a colleague noted, “very much interested in the case, more so than anybody else.”

The interrogators questioned Peiper’s men aggressively. They used tricks, deception, and ruses—many suggested by Perl—to extract confessions. “Bill was always thinking of some trick or some new angle…it was always a matter of cleverness, the use of some psychological trick,” Captain Ralph Shumacker, a war-crimes prosecutor, later recalled.

The investigators started with the enlisted men, telling them falsely that they were interested in prosecuting only those who had ordered the killings and that the SS men had nothing to lose by confessing since obedience to orders was a defense to a war crime. These techniques worked. “The SS soldier was so completely indoctrinated with the Fuehrer concept that he apparently considered murdering prisoners of no consequence if a corporal, sergeant, or anyone of higher rank ordered it done,” Shumacker said. Once an enlisted man had confessed, the investigators used his statement against him and those he had implicated.

Cooperating German soldiers at Schwäbisch Hall pumped fellow prisoners for incriminating information. Following the instructions of the American investigators, they lied to their comrades, saying they had gotten off with light sentences because they had confessed. Investigators also bluffed, telling suspects they had bugged their cells and overheard incriminating conversations. They even fabricated a story that the United States was out for blood because the son of a senator was one of the Malmedy victims. With officers, they used a different approach: Peiper said Perl had assured him that if he took responsibility for the massacre, his men would go free.

Mock trials were the most controversial technique. A suspect was brought into a room containing a table draped with a black cloth, a candle at each end, and a crucifix in the middle. Several uniformed Americans sat behind the table, pretending to be judges. On the other side of the table were two other Americans—one acting as a hostile prosecutor, the other a sympathetic defense attorney. The prosecutor harangued the suspect, sometimes bringing in a cooperating German soldier to hurl accusations at the prisoner. By the end of the encounter, the suspect believed he had been convicted of a war crime. After the prisoner went back to his cell, the sympathetic defense attorney visited him, telling him he had been sentenced to death but could still save himself by confessing and implicating others.

Investigators had still heavier-handed tactics. They threatened to take away ration cards from the families of uncooperative suspects—a serious matter since food was in short supply in postwar Germany. At times, things may have gotten physical. Herbert K. Sloane of the War Crimes Branch recalled bringing a prisoner, Heinz Stickel, to Schwäbisch Hall in April 1946 and turning him over to investigator Harry W. Thon, a 36-year-old former GI raised in Germany. “I bet I can get a confession before you take off your raincoat,” Thon boasted. He ordered Stickel to remove his shirt to see if his arm bore an SS tattoo. When Stickel didn’t obey quickly enough, Sloane said Thon punched him and then grilled Stickel, who admitted firing a machine gun at the American prisoners. “See, there is your confession,” Thon told Sloane.

Within four months, the War Crimes Branch had put the case together. The investigators had gotten statements from more than 70 of Peiper’s men, confessing or implicating others. In April 1946, prosecutors charged Peiper and 72 of his men as war criminals. The complaint alleged that the defendants—both officers and enlisted men—did “willfully, deliberately and wrongfully permit, encourage, aid, abet and participate in the killing, shooting, ill-treatment, abuse and torture” of the American prisoners at Malmedy. Because Peiper was not present at the massacre, he was charged as an accessory before the fact. His pre-battle orders had authorized and encouraged his troops to murder prisoners, prosecutors alleged, making him as culpable as if he had pulled the trigger himself.

The charges involved a violation of conventional rules of war, and the trial was assigned to a U.S. Army tribunal. Colonel Willis M. Everett Jr., 46, was appointed lead defense counsel. A reserve army officer since 1923 and an attorney since 1924, Everett had spent the war ferreting out Communists and Axis sympathizers near the Manhattan Project’s production facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Assisting him were five other American attorneys and six German lawyers. The chief prosecutor was Lieutenant Colonel Burton F. Ellis, 42; neither Everett nor Ellis had ever tried a criminal case.

Six Malmedy survivors traveled to Germany for the trial. Kenneth Ahrens said he was there “for the poor guys who weren’t as lucky as me. For them and their families back in the States.” Former Lieutenant Virgil P. Lary Jr. said he would have come on his “hands and knees” to bring the killers to justice. Before the trial, Lary confronted Peiper in his cell, demanding to know “why your outfit committed such a crime.” He said Peiper told him: “We had orders to do so…. I take full responsibility.” Lary also had a surprise for prosecutors. He thought he could pick out the soldier whose pistol shots had started the massacre. The SS men were paraded past him, and Lary identified a 23-year-old private, Georg Fleps, as the shooter.

The trial of the 73 defendants began on May 16, 1946. The defendants sat together, about a dozen abreast and several rows deep, wearing uniforms stripped of rank, insignia, and decorations. Each wore a numbered placard for identification. Peiper was number 42. Only nine defendants took the stand, and they didn’t help themselves. “Like a bunch of drowning rats, they were turning on each other,” one of the defense attorneys recalled.

Although fluent in English, Peiper testified in German. Prosecutors introduced a damning statement the SS man had given two months earlier; he hadn’t needed to order his subordinates to shoot prisoners, he had said then, because they were all “experienced officers” to whom it was “obvious” that prisoners would have to be shot.

The trial ended on July 11, 1946, and the seven military judges convicted all 73 defendants. Five days later, the court sentenced 43, including Peiper, to death by hanging; 22 to life imprisonment; and eight to jail terms of 10 to 20 years. Peiper and his men would serve their sentences or await execution at Landsberg prison in Bavaria, the site of Adolf Hitler’s incarceration after his failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. Their sentences would stand unless modified by the U.S. European Theater commander, General Lucius D. Clay.

THE METHODS Perl and his colleagues had used had been brought out at trial and formed the basis of the SS men’s defense. These methods troubled General Clay, and he questioned the reliability of the statements Perl and his men had obtained. Army regulations prohibited “threats, duress in any form, physical violence, or promises of immunity or mitigation of punishment” during questioning. On March 20, 1948, Clay commuted 31 of the 43 death sentences to prison terms, leaving only Peiper and 11 others on death row. “If there was any doubt, any doubt, I commuted the sentence,” Clay said. He also freed 13 other defendants because of insufficient evidence.

Defense counsel Everett believed all the convictions were fatally flawed because of how the confessions had been secured. Now a civilian, he wanted to bring the case before American courts because U.S. law treated coerced confessions as inherently unreliable. In May 1948, he filed a petition with the U.S. Supreme Court; the threshold question was whether an American court had jurisdiction of a case tried in Germany for war crimes committed in Belgium. Four justices found a lack of jurisdiction; four others wanted to hear more. The deciding ninth vote belonged to Justice Robert H. Jackson, who disqualified himself because he had served as the chief U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg war-crimes trials. The tie vote meant the Supreme Court would not hear the case.

German attorneys obtained affidavits from Peiper’s men repudiating their earlier confessions because of alleged coercion and physical abuse. SS sergeant Otto Eble, for example, claimed investigators had put lit matches under his fingernails to make him talk. Edouard Knorr, a German dentist who had treated prisoners at Schwäbisch Hall, insisted that more than a dozen men had had teeth knocked out by American fists. U.S. officials were skeptical because they knew the prisoners had much to gain by recanting. Still, the deceptive tactics the interrogators had used—confirmed on September 14, 1948, by an army commission chaired by former Texas judge Gordon Simpson—gave them pause.

In Germany, the prisoners’ claims were accepted as true, sparking anger among the general population who saw the war-crimes trials as victor’s justice—a penalty for losing the war. German veterans felt the prisoners were simply soldiers who had fought for their country. A German revisionist even claimed Malmedy was not a war crime at all because Peiper’s men had mistaken the Americans in the field—their arms raised in surrender—for combatants.

German public opinion mattered. The Iron Curtain had descended on Europe and Germany was partitioned, with the Soviet Union controlling the eastern section and the United States, France, and Britain occupying the western part. The U.S. needed West Germany as a strong ally and a buffer against Communist expansion and would do “almost anything to soothe and cajole German opinion,” the New York Times reported in 1952. With the imprisonment of Peiper and his men a source of friction, the U.S. Senate wanted to get to the bottom of what had happened at Schwäbisch Hall.

IN 1949, THE SENATE Armed Services Committee held hearings, calling 108 witnesses over five months. Freshman Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin, grabbed the spotlight early on, badgering witnesses and expressing sympathy for Peiper’s men. McCarthy stormed out of the hearings when the panel refused to give army investigators lie-detector tests. As a parting shot, he accused William Perl and his colleagues of “Hitlerian tactics, Fascist interrogation, and the communistic brand of justice.” Less than a year later, McCarthy would find his ticket to fame when he claimed Communists had infiltrated the State Department.

The Senate committee report, issued on October 13, 1949, found no army-sanctioned physical mistreatment and rejected the most lurid abuse claims. The committee disbelieved Otto Eble because he had used a false name, his fingers showed no scars from the torture he claimed, and he had several fraud-related convictions before the war. It doubted the veracity of Dr. Knorr, who had died before the hearings, because he had conveniently destroyed all dental records for the German prisoners despite his standard practice of keeping patient records for 10 years.

Nevertheless, the committee suspected some physical abuse: “in individual and isolated cases there may have been instances where individuals were slapped, shoved around, or possibly struck,” likely “the irresponsible act of an individual in the heat of anger.” It called the interrogation trickery “a grave mistake,” faulting the army for using untrained criminal investigators whose hatred for the Nazis may have convinced them that the end justified the means.

Germans continued to agitate on behalf of war criminals held by the United States, Britain, and France. German religious leaders pushed for their freedom; an organization of two million German veterans adopted a resolution demanding the war-criminal issue be, in their words, “satisfactorily settled”; and a West German parliamentary committee pressed American officials for clemency.

In March 1949, General Clay commuted seven more Malmedy death sentences. On January 31, 1951, his successor, General Thomas T. Handy, reduced the remaining five death sentences, including Peiper’s, to life imprisonment and freed other Malmedy prisoners. On May 12, 1954, General William M. Hoge, Handy’s successor, reduced Peiper’s life sentence to 35 years.

The Germans were not satisfied. They saw the sentence reductions and the release of some prisoners as political opportunism designed to placate them and pushed for more. Behind the scenes, West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer demanded “immediate machinery for clemency” for war criminals. He warned the State Department of the “considerable psychological and public opinion problems in Germany” caused by “the agitation of various soldiers and veterans organizations.”

In 1955, the Paris-Bonn conventions restored West German sovereignty and ended Allied military occupation. The treaty took the war-criminals issue out of American hands and gave it to a Mixed Parole and Clemency Board, made up of three West German representatives and one each from the United States, Britain, and France. The treaty decreed that the board’s members were not “subject to instructions from the appointing governments,” and a unanimous board decision was unreviewable—both of which would allow the U.S. government to wash its hands of any unpopular parole decision. The State Department appointed a career diplomat, Edwin A. Plitt, to the board.

The board quickly drew fire when it released General Sepp Dietrich, whose orders had discouraged the taking of prisoners during the Ardennes offensive. American veterans protested, but U.S. officials noted the board did not answer to them and that they had no say in Plitt’s vote. The American Legion demanded Plitt’s removal, and on January 25, 1956, the State Department replaced him with former senator Robert W. Upton of New Hampshire. Even more alarming to veterans were reports that Peiper would soon go free, but the State Department dismissed those rumors, saying it had no information “to substantiate news report that Mixed Board of Clemency and Parole is about to release Col. Peiper.” Senator Estes Kefauver, a Democrat from Tennessee, urged that Peiper be kept behind bars, calling Peiper and his men “the worst kind of sadistic murderers.”

When Upton arrived in West Germany in March 1956 to join the Mixed Board, he received a shock. Five months earlier, on October 5, 1955, the board had secretly and unanimously voted to free Peiper. It was a fait accompli, and Peiper would be released as soon as his parole conditions were finalized.

When the 41-year-old Peiper walked through the gates of Landsberg prison on December 22, 1956, reactions in the United States were surprisingly mild. Only survivors and veterans’ groups objected strongly. For the survivors, said Virgil Lary, “our hearts are sick after each release.” The American Legion called Peiper’s parole “a callous, criminal betrayal of trust”; the Veterans’ Civic League of New Jersey asked the government to “place the barbaric Colonel Peiper back in jail where he belongs.” The U.S. government, however, was powerless. The Paris-Bonn treaty had seen to that.

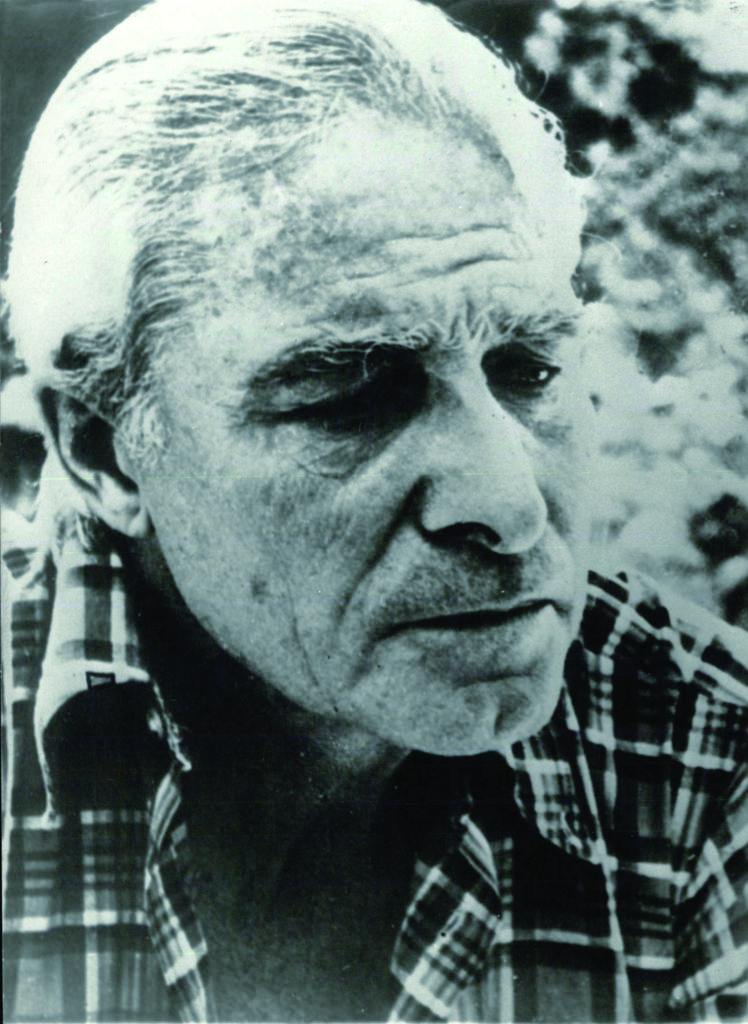

Peiper went to work for Porsche and later Volkswagen in Germany. He lamented his years in prison. “I have paid. I have paid dearly,” he said. In 1972, he moved to the small French village of Traves, 80 miles from the German border, and worked as a translator. Four years later, a reporter discovered his whereabouts after Peiper used his real name to order chicken wire at a local hardware store. The French Communist newspaper, L’Humanité, published an exposé of the notorious war criminal living quietly among the French, and the former colonel was defiant. “If I am here,” he told reporters, “it is because in 1940 the French were without courage.”

On the night of July 13, 1976, unknown individuals firebombed Peiper’s house; he died in the blaze, his body burned beyond recognition. His killers were never found. In the end, the man who had survived the brutal fighting of the Eastern and Western fronts and evaded the U.S. military justice system could not escape his past. To the now middle-aged American veterans of the European Theater, justice had finally been served. ✯

This article was published in the April 2020 issue of World War II.