The Union Army’s 17th Missouri Infantry arrived at Bridgeport, Ala., on the Tennessee River in late November 1863. Known as the Western Turner Rifles, they fought in Maj. Gen. Peter Osterhaus’ 1st Division in the Army of the Tennessee’s 15th Corps, part of Ulysses S. Grant’s command reinforcing besieged Chattanooga, Tenn. “We have had hard times since I left you,” wrote Private William Heldman of the 17th. “First we had to fight every day and now we have marched about 200 miles without one day’s rest and not enough to eat. They are making a railroad bridge here across the river today. I don’t think we will stay here long. We have got the right wing of the army.”

Grant’s arrival in Chattanooga on October 23 had effectively opened a key Union supply chain into the city known as the “Cracker Line”—welcome relief not only for the starving Federal soldiers inside the city but also the army’s animals. “The men had been on half rations of hard bread for a considerable time,” Grant would note. “The besieged Union troops were happy to get the food supplies but they were without sufficient shoes or other clothing suitable for the advancing [winter] season.”

That’s not to say their counterparts in gray weren’t suffering, too. The torrential rains had muddied the roads to the Confederate positions, significantly preventing the routine flow of supplies. As President Jefferson Davis noted of the Army of Tennessee during an October 10 visit: “[T]hey had given still higher evidence of courage, patriotism, and resolute determination to live freemen, or die freemen, by their patient endurance and buoyant, cheerful spirits, amid privations and suffering from half-rations, thin blankets, ragged clothes, and shoeless feet, than given by baring their breasts to the enemy.”

Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee recalled that as Davis and his staff galloped by the Tennessee troops, the soldiers mixed cheers with chants of “Send us something to eat, Massa Jeff! I’m hungry!” Those supplications were answered by the end of October; Davis had made sure his men were much better fed and clothed. The 19th Louisiana Infantry, in Colonel Randall Gibson’s Brigade occupying Missionary Ridge, were among those to draw jackets, pants, caps, shirts, drawers, shoes, and blankets. Private George A. Bruton, however, lamented the lack of a key item in winter time, writing to his sister: “As for clothes, I now have plenty of evry thing but socks. Socks can not be had for love or money.”

Douglas John Cater, the regiment’s drum major, described the unbalanced food situation: “Our cooks were with the wagons in the rear and brought rations to us between Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. For the first eight days these rations consisted of cornbread and bran coffee, but on the eighth day, Ram[e]y Lafitte, our company cook, got in possession of a yearling calf and made jerked beef of it. This was in addition to our bill of fare and we ate it with good relish.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Despite the supply relief, the Louisianans were disappointed to see some of their own moving on to another brigade. In General Braxton Bragg’s reorganization of his forces, the 5th Company, Washington (La.) Artillery was separated from Gibson’s Brigade, resulting in “quite a commotion.” Gibson’s infantryman shouted to the artillerists, “Boys, you will lose your guns to-day; we will not be there to stand by you.”

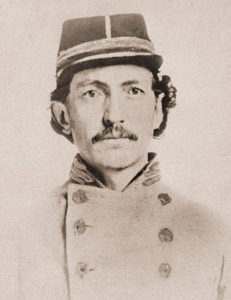

A petition was drawn up requesting that the Louisianans be left to fight together, circulated by the 19th’s commander, Colonel Wesley Parker Winans. To no avail. Recalled one gunner: “[I]t was the first time the battery had been separated from Louisiana infantry units.”

The Confederates began bracing for “a big fight every day.” Wrote Lafitte: “[W]e are station[ed] on a high Ridge from where we can see Yankee tents. They are just as thick as bees…” Bruton’s patriotic ferver was particularly apparent. “Old Jeff Davis is determined to keep us here until my heads are as white as coton or I die with old age,” he wrote. “A great many men are geting out of servis by diserting but I will stay here for ever before I disert as many have done.”

Nevertheless, as often happened with two armies in such close proximity for an extended period, enemy soldiers began trading goods with each other. Private William Hamner of the 19th Louisiana told his family that he had done so several times, and drum major Cater wrote that he saw his men “giving tobacco [to the Yankees] in exchange for coffee. In this way we found out that they too were sometimes almost without provisions.”

Lookout Mountain

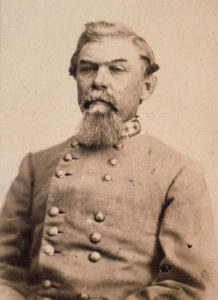

On November 4, Braxton Bragg directed Lt. Gen. James Longstreet and his two divisions, reassigned from the Army of Northern Virginia, to advance toward Knoxville to deal with the threat posed by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Ohio. Burnside had occupied the important city, only a few days’ march north of Chattanooga. It was up to Longstreet not only to keep Burnside’s army away from Bragg’s, but also to break the Union occupation of Knoxville.

Grant responded quickly when he learned of Longstreet’s departure. On November 23, he sent troops forward to capture a lightly occupied Confederate observation post on Orchard Knob, a small hill midway between Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge. Bragg responded to the loss of Orchard Knob by repositioning sections of his army. The 19th Louisiana’s longtime division commander, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, was given command of the left side of the forces on Missionary Ridge, while Lt. Gen. William Hardee assumed command on the right. “The night we got to the Ridge, though late, thousands of camp fires were sparkling in the valley beneath,” wrote John Jackman of the 9th Kentucky Infantry. “A belt of fires encircled Chattanooga, showing the lines of the enemy and all around the base of the Ridge, our fires were glowing.”

The next Union target was Lookout Mountain, which a 10,000-man force commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker captured on November 24. Unable to provide assistance, the men in the Washington Artillery were left to observe the battle as it unfolded. The famed gunners also took time “to partake of some delicacies received from far off Louisiana”—joined by Breckinridge, his staff, and other dignitaries.

Lieutenant James E. Carraway of the 19th Louisiana had a prime view of Hooker’s attack:

“We were on picket duty in the valley just below and to the right of the battlefield. We could see the charges made by the opposing lines as they wavered to and fro. The mountaintop was made dense with smoke and the air hideous with the cries and groans of the wounded. It was a grand yet solemn sight to behold. And at a late hour of the night, ere the battle ceased, the moon which was shining brightly was suddenly enveloped in darkness as if to show the powers of heaven upon the cruelties of war, and the painting of the earth below red with the blood of human lives. The battle at last hushed. Adjutant Ben Broughton of our regiment visited the picket line, having brought and almost whisperingly delivered orders to fall back. We took up the line of march east, and at the break of day we were ascending the west side of Missionary Ridge, which with its projecting rocks was difficult to do, and not without our lines becoming frequently disordered. Yet by sunup we had reached its summit….”

The Union occupation of Lookout Mountain severely exposed Bragg’s left flank on Missionary Ridge, which required another troop shift.

“After midnight having repulsed every attack of the Rebels, our Div. had a few hours rest with only an occasional picket shot along our line in our front, which ceased entirely towards dawn of the 25th of Nov.–” recalled Captain John G. Langguth of the 17th Missouri. “Soon daylight revealed the fact that the Johnnies had left Lookout Mt. and the Union troops were in full possession. With the rising of the Sun on that beautiful clear Nov morning, a mighty shout arose from the troops on the Lookout upon their seeing the Stars & Stripes again floating proudly to the breeze on the White House [today’s Cravens House, which the home’s owner called “Alta Vista” at the time]….”

Fierce Fighting on the Ridge

As Colonel Winans had predicted upon his arrival on Missionary Ridge, pieces had begun to fall in place. “Another great fight is imminent at Chattanooga,” he wrote to this sister, Mary Winans Wall. “…I expect in the course of a month to test my luck or fate in the Waterloo of this revolution. Both sides are reinforcing—.”

The 19th Louisiana stacked arms near Breckinridge’s headquarters and hurriedly cooked up the five days’ rations that they had been issued, all the while allowing themselves ample time in the frigid temperatures to enjoy the heat of the fires. “[Bragg] ordered the line in single file which gave it the appearance of an army twice its real size,” remembered Carraway. “Then came an order for each company to build breastworks equal to its front, and all this was done while the dense fog hung between us and the enemy. But the greatest difficulty confronting us just at this moment was procuring of picks, spades, and other implements to enable us to build the breastworks which we had been ordered to do. Nothing of the kind could be commanded, and if ever such things were possessed by our army they were far away with the wagon trains.”

Recalled Langguth: “In due time after coffee, hardtack and replenishing ammunition in our cartridge boxes, the Union troops, our Division in the lead began their march down the mountain winding their way like a large blue snake in the warm rays of the morning Sun. It was a beautiful morning and a grand Panorama—the distant thunder of Sherman’s artillery on the left of the line, the camps around and in Chattanooga alive with massing troops, 1,000’s of glistening guns, all moving in one direction, towards Bragg’s host’s [sic] on Missionary Ridge.”

For Carraway, the 19th Louisiana’s new position elicited strong memories. “The face of the mountaintop…was covered with rocks of almost every conceivable shape and size,” he wrote. “We could no longer hold them [the Federals] in check, and for a while at different places along the line the Rebs and the Yanks were engaged in hand to hand combat, guns were clubed, bayonets used and the artillery swabs instead of their being used in driving home the charge the empty guns were hurled in the face of the enemy until the line was enveloped in smoke.”

As the regiment valiantly tried to rally, its ammunition began to dwindle. To stem the approaching tide of blue, some men resorted to throwing rocks.

Already facing an attack from the base of the ridge, the Louisianans were shocked to watch the disintegration of the brigade to their left. Because of the extremely loud gunfire, Winans had split his command into two wings, with Captains Winfrey B. Scott and Michael G. Pearson operating each flank and Winans astride his horse, Delia, maintaining control of the center of the regiment. This allowed him to relay commands easier amid the sounds of battle.

The enemy “advanced and crossed Chickamauga Creek,” Cater recalled. “Our men in rifle pits on the ridge were about one man every ten or fifteen feet, and we were attacked in front. We could not check the advance of the enemy because they were three lines deep and our men were in single file. We did some good shooting but there were not enough of us. When the Federals which were on the left of us in the ridge were coming from that direction, making an enfilading fire on us, it was either leave the trenches or be killed, so we left them. We didn’t leave soon enough because we lost many of our best men before we got out of range of their guns. Our loved Col. Winans was killed on this ridge.”

Scott praised his men in his after-action report. “[T]he enemy made a gallant assault but were soon scattered and driven back….,” he wrote. “Never did I witness men who appeared more cool, deliberate, and confident of being able to repel any force that could be brought against them than did our men on this occasion. No one seemed to dream of being driven from our position….It was about this time the enemy began to fall back on the first charge that Colonel Winans received his wound and was carried to the rear.”

“A part of the regiment was rallied and gave the enemy fight again,” Scott would recall, “but we could not get the regiment reformed until we got near the bridge….”

Of the ensuing Union sweep up Missionary Ridge, Langguth wrote:

“Our column—Hooker’s were out of sight[—]reached the Valley without molestations, moving across Chattanooga Creek and thus forming the extreme Right of Genl. Grant’s Army; while thus marching through the woods, the Rebels send a shell occasionally our way. Our movements now brought us to the rear of the Rebel left (Breckinridge’s Corps), some of the Johnnies showed their heads but were quickly induced to skedaddle or surrender, the terrible firing to our left indicated the charge of [Maj. Gen. George] Thomas’ troops, which soon became evident by a whole brigade of Confederates running our way & were captured, bag & baggage, with many stands of colors. Our Division then halted and we witnessed one of the greatest sights a soldier can ever witness: A Conquering Army. Regiment after regiment swept over the brow of Missionary Ridge amid hurrahs and excitement, following up the enemy, every man in his place in company front, stepping brisk & fresh with the stars & stripes carried proudly aloft, the many days or weeks of hardship were forgotten and only ‘Forward!’ ‘Forward!’ was their cry until late in the night.”

In addition to describing Winans’ fall, Carraway divulged his own near-fatal wounding that afternoon:

“[Winans] who was in command of our regiment was killed (hit by a minieball in the neck which failed to stagger him yet he was in ten minutes, even walked away from the line of battle a few steps to the rear) and the remains of the gallant [Winans] was all that was left to us. At this command of the regiment fell into the willing and gallant hands of Capt. Pierson [sic] who was the senior Captain of the regiment. [The] regiment…had retreated more than one hundred yards from in the rear of the position from which we had been fighting, [soon] to rally. It was here, halting in obedience to the command of Captain Pierson I was shot down on the rocky mountain.

“As I lay there in this almost half conscious condition, four of my men threw a folding litter on the ground beside me and placed my helpless body on it. Shot was raining around us, raining a perfect whirlwind of dust and dirt. These true friends had not borne me far ere Andrew Davis, one of the bearers, fell with his back broken. He never uttered a word. This dropped me by the side of my dying companion, and my shoulder was resting on his left arm. By this time I had located my wound. It was a crease in the back of my neck. So by an effort I arose to my feet. I knew the direction my command had gone, and also the one I wanted to go, but at first my legs were tottery and refused to lead me in that direction.

“The last rebel out of sight, not a soul in view except those who were seeking my life. I had not gone more than two hundred yards when in crossing a ravine I saw standing not far from me, in a sort of hillside ravine the horse [Delia] of our dead [colonel], who seemed to be waiting patiently for the coming of [her] master. I walked up to and climbed on…and made my way eastward.”

The Search for Winans

Langguth was of course ecstatic in victory, crowing, “[T]hat great battle of the Civil War, which will ever stand as one of the greatest achievements of the American soldier—it was a picture no painter or artist can ever portray.” As the defeated Confederates moved south, they mounted a strong defense at nearby Taylor’s Ridge. Then, with harsher weather approaching, Bragg’s army settled into winter quarters at Dalton, Ga.

Back in Louisiana, grief for lost loved ones was rampant. Mary Wall, Winans’ sister, was no exception. So distraught from not knowing what had happened to her brother’s remains, she wrote Hardee asking his assistance. The heart-wrenching missive said in part: “I had only one brother. Oh, how I loved him! He was handsome, popular, useful, necessary to many. On November 25, 1863, he was shot. He walked to the bottom of the hill, by the assistance of a friend. The surgeon told him that his wound was ‘mortal.’ He said, ‘My regiment acted gallantly today.’ The Federals now passing our folks, and they were obliged to fall back. My brother was left in charge of a young man of his regiment while ‘they all passed by and left their Colonel alone to die.’ This man reports he took off the Colonel’s pistol, and belt, leaned him against a tree and left him ‘not yet dead.’”

Mary implored Hardee to find out if anyone in his command was by Winans when he passed. “Did any kind soul give him water or hold his dying head? Did my brother say anything? Was he dead when the Federals found him and was he buried in the common graves? If he had a separate grave, can anyone identify it? My brother was the only ‘field officer’ who fell that day. He was about 5′8″ tall, had light hair, I think he had a mustache, his eyes were black, and his feet and hands were very small. I suppose some of his apparel was marked ‘W P W’ or ‘Winans.’ He had on gold or heavily gilded spurs, these had his name on them and the name of the giver, C[amp]. Flournoy. He wore his wife’s double cased gold watch. The stars on his coat were gold. I mention these particulars that you may be able to identify what person I inquire after. Though I mourn him as dead and it nearly kills me at the bottom of my heart. [C]an I suppose if you can recover those spurs and the watch, the person from whom you get them will want them as mementoes. I promise to pay for them.”

Hardee inquired if the commanders and men in the Louisiana brigade or other nearby troops knew anything about Winans, without success. Having known Hooker while at West Point, Hardee decided to query the Union commander, who had graduated the year before him. Surely, someone in the Northern forces would remember a Confederate field grade officer wounded on the left side of the ridge where Hooker and his men under Generals Cruft, Geary, and Osterhaus had charged upon and overrun the Louisianans’ position atop the ridge. Hooker agreed to assist his old fellow cadet in Mary’s quest to determine her brother’s final hours. He asked his three division commanders to question those in their command on what might have happened to Winans. Unfortunately, no one in the 17th Missouri or any other unit in Osterhaus’ command recalled seeing the mortally wounded Winans.

Geary was a bit more informative after collecting the reports of men under his command. He replied, “Two of my surgeons…think his name was Winans. They were called by some privates of my lines which they saw was that of a rebel colonel. They did not examine it. The casualty was about a quarter mile to our right from the final resting place of Gen. Hooker’s command for the night. A rebel officer said to be a colonel was brought to a house by them as he was reported mortally wounded.”

At nearby Ringgold, Ga., Winans was reportedly cared for by a Mrs. W. Donald, but little else was known. Agreeing with Geary’s findings, Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard forwarded the results to Hooker, who in turn sent the new information to Hardee via a flag of truce. Cruft remained an important part of the final key to obtaining further details on what had happened to Winans.

“I…made the assault on the extreme left of the enemy’s line,” Cruft wrote in his report. “As our lines moved northward along the ridge, I spied a Confederate officer who appeared to be mortally wounded & in great agony. He was reclining on the ground & leaning back against a tree. He spoke to me and asked to be cared for. I promised to send him a surgeon as soon as possible. The lines were now pressed forward at a charging pace and the interview with the officer was but momentary. A party of Confederate prisoners happening to be nearby, I ordered one of them to care for the officer & stay with him & if possible assist him to the rear or down the hill. One of the prisoners stepped out and said, ‘[I] would stay with him as he belonged to his regiment.’ I thought at the time that the wounded person was a field officer but do not know this to be so. He was well dressed and was an intelligent & gentlemanly man. He did not state his name or regiment or rank.”

The general was attempting to provide as many details as possible to Mary to bring her some peace. In addition, Cruft noted in his response, “A surgeon was sent back, according to my hurried promise to look to him but no report as to his condition or fate. Some of my staff think they can remember a resemblance to the description given in the letter of Colonel Winans’ sister. The whole thing was momentary. If this officer was Colonel Winans he probably died where he was seen by my staff, myself, or a very short way down the hill & was buried with the other dead. The wounded of the Confederates lying on the ground fought on by my division were all collected & sent, in the division ambulances, to Chattanooga during the night & the dead were buried soon after daylight the following morning by a burial detail. I saw two other Confederate officers lying on the field severely wounded whom I supposed to be at the time line officers.”

These men likely both belonged to the 19th Louisiana, as Captain Andrew J. Handly was mortally wounded and Lieutenant Barney H. Sears suffered a bad wound to the head, from which it took him several months to recuperate.

Cruft had no further information for Mary, but he did mention in his missive to Hooker, “[N]or was any portion of the personal effects described reported or heard of by me.” The query for information among the Federal commanders did have one last reply. Wanting a thorough inquiry, each division leader sent out a request to each regiment, who in turn sent the information to their company captains. Captain John B. Mattison of the 19th U.S. Infantry, who also served as the unit’s provost marshal, sent a message up the line that provided more details of Winans’ mortal wounding. He wrote, “[Here is the] information from the officers of this command relative to Colonel Winans, 19th Louisiana (Rebel) Vols….In reply, I have to state he was the only field officer of the enemy killed in front of this command. He was shot by a non-commissioned officer of the 18th Infantry. The officer in question was wounded at the left of the hilltop, along the southern end of the ridge. He was seen to fall from his horse. He had been injured in the left side of the abdomen passing through the body. The brigade inspector, in posting the pickets that evening had [Winans] removed to a log cabin near the picket line.”

Exact locations of the Confederate burials are unknown. When General Thomas was asked if he wanted the bodies buried by state, he replied, “No, no, mix them up. I’m tired of States’ Rights.” Although Mary Winans Wall never found her beloved brother’s final resting place, she knew Hardee and Hooker had done their best to bring her some peaceful closure. Amid the horror of war, humanity won out.

Richard H. Holloway, an ACW advisory board member, thanks Rodney Huffman, Beth Horner, and Robert Sears for their help with this article.