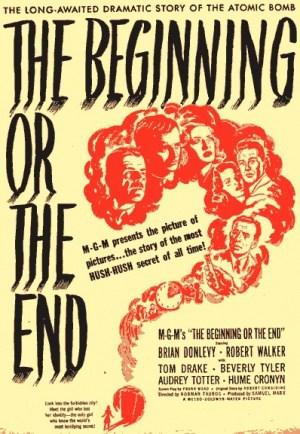

When Hollywood’s largest studio, MGM, decided in autumn 1945 to create the first major movie about the creation and use of the atomic bomb, producers naturally sought the approval of key Manhattan Project scientists. The movie, in fact, had been inspired by an urgent letter written by a young atomic scientist. Before coming to work at the Oak Ridge site in Tennessee, Edward Tompkins had taught high school chemistry in Iowa. Writing to actress Donna Reed, a former student, Tompkins pleaded with her to get Hollywood to make a movie that would warn the world about the dangers of building even more powerful weapons, leading to an inevitable nuclear arms race and perhaps the end of civilization.

Reed happened to be well-positioned to get such a film made. Her new husband, Tony Owen, was a talent agent and friend of MGM studio chief Louis B. Mayer. Within days Owen had pitched the idea to Mayer, who immediately signed off on a docudrama. Mayer promised that The Beginning or the End, as the film came to be titled, would be the “most important” movie he’d ever release. To achieve that, however, the studio would have to get signed releases from the leading characters. These figures ranged from military officers to scientists Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard, Enrico Fermi, and the scientific chief at Los Alamos in New Mexico, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

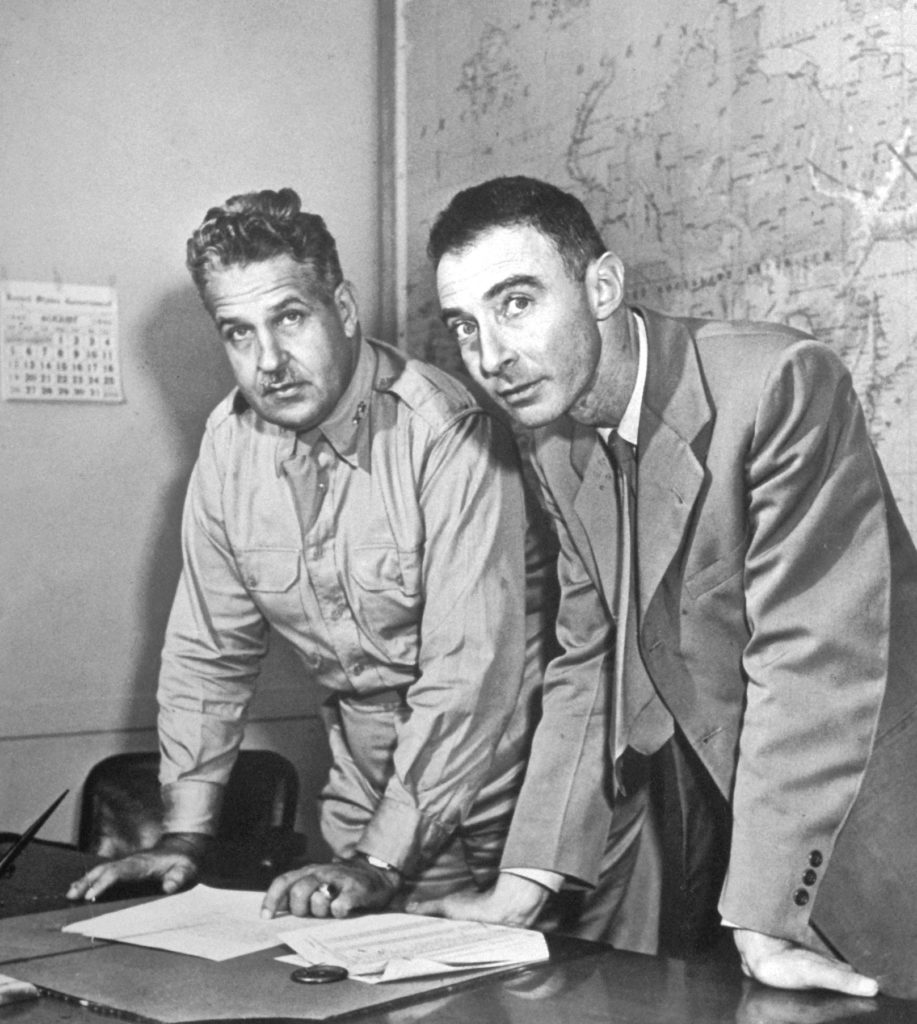

The key military man, Lt. Gen. Leslie R. Groves, overall director of the Manhattan Project, quickly signed a contract and—in the most crucial move of the film’s trajectory—secured the right from the studio to approve the script. Groves also negotiated a $10,000 fee—today, $130,000—for serving as chief adviser. President Harry Truman received a similar veto power. Among other moves, Truman wielded his authority to get an actor cast to play him fired and to order a costly re-take to bolster his defense for using the bomb against two Japanese cities. Thanks to Groves and Truman, the movie’s message would lurch far from the original goal of a cinematic warning, becoming an endorsement of the bomb and its use against Japan.

None of the scientists involved were to be paid or given script approval, but MGM could not proceed unless these individuals signed releases. This led in early 1946 to rather desperate attempts to gain the scientists’ signatures, after sending them portions of the script. For a time, the studio seemed unlikely to make an ally of the very skeptical and always outspoken Szilard. Einstein, now leading a public campaign for international control of the atom and convinced there had been no need to use the bomb against Japan, was so hostile to the idea that he penned a dismissive letter to Mayer. “Although I am not much of a moviegoer, I do know from the tenor of earlier films that have come out of your studio that you will understand my reasons,” Einstein wrote. “I find that the whole film is written too much from the point of view of the Army and the Army leader of the project, whose influence was not always in the direction which one would desire from the point of view of humanity.”

Mayer replied that he “was most anxious to have the picture made,” adding, “As American citizens we are bound to respect the viewpoint of our government….It must be realized that dramatic truth is just as compelling a requirement to us as veritable truth is to a scientist.” Einstein, understandably, still balked.

After MGM invited Szilard to Hollywood and let him lightly revise the script’s depiction of his involvement in early atomic experiments, he offered his approval. Szilard convinced his reluctant friend Einstein to sign on as well, more out of fatigue than anything else. The film, however, would make no mention of Szilard’s forceful efforts to slow Truman’s decision to drop the first bomb.

Oppenheimer characteristically acted the Sphinx for months, one moment mocking the project, then acting intrigued, never deigning to read a script. He briefly installed David Hawkins, a former aide at Los Alamos, at MGM to serve as his eyes and ears. Oppenheimer, however, sat for two lengthy interviews with novelist Ayn Rand, at work on a competing screenplay for producer Hal Wallis at Paramount. The Paramount project never reached fruition, but Rand would later base a key character in her novel Atlas Shrugged on Oppenheimer.

MGM grew so discouraged about gaining Oppenheimer’s permission the studio for a time renamed his character “Whittier.” After finally reading the script in April 1946—he found its depiction of scientists often laughable—Oppenheimer hosted the movie’s producer, MGM’s Sam Marx, for dinner. Over a meal at his hillside home in Berkeley, California, Oppenheimer lobbied for revisions. When Marx agreed to attend to them, Oppenheimer, observing that the film’s characters often acted “stiff and idiotic,” gave verbal approval. Afterward he confessed to a friend that perhaps he had made a mistake—the script was filled with “ignorance and bad writing” and despite the revisions would never be any good.

While all this was transpiring, the FBI was closely monitoring Einstein’s mail, and shadowing Szilard and Oppenheimer. Bureau director J. Edgar Hoover viewed the entire Manhattan Project team as possible security risks for harboring leftwing views; Oppenheimer was alleged to have belonged to the Communist Party. The FBI tapped his home phone in Berkeley. On at least one occasion, agents taped Kitty Oppenheimer discussing the MGM movie with former Los Alamos staffer turned Hollywood factotum David Hawkins.

One evening in May 1946, FBI agents taped and transcribed a revealing cross-country call between the Oppenheimers that’s detailed for the first time in my new book, The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, published today by The New Press.

Robert was back East. Near the end of their lengthy conversation, Kitty Oppenheimer informed her husband that an actor named “Hugh Cronin,” as the name was transcribed, had sent him a letter explaining “why he would like to be you.”

Robert: “Bill Cronin?”

Kitty: “Hugh Cronin—that bloke that belongs to MGM.”

(The reference actually was to actor Hume Cronyn, cast by MGM to portray Oppenheimer.)

Robert: “Well, I’ll tell you what I did on this. This very ugly creature [Colonel William A. Consodine, a top Groves aide] called me and said that Marx had said it was all right and would I sign the release, and I said sure. I got the release and I signed it with a paragraph written in saying that all of this is subject to my receipt of a statement from Mr. Sam Marx that he believes the changes that have been made are satisfactory.”

Possibly to re-assure Kitty, Robert told her David Hawkins was still at the studio.

Kitty: “Oh.”

Robert: “Well, I didn’t think there was anything else to do. I don’t want anything from them and if I can work on his [Marx’s] conscience, that is the best angle I have. It just isn’t worth anything otherwise, darling.”

The signal began fading in and out.

Robert: “The FBI must have just hung up.”

Kitty (as transcribed): “Giggles.”

Robert: “The only thing we can do there is to try to persuade them to do a decent job.”

MGM released The Beginning or the End in February 1947. Largely reduced to pro-bomb propaganda and laced with romantic sub-plots and factual errors, the film drew mixed notices and did weak box office. Reviewing the first A-bomb feature for the new publication Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Oak Ridge chemist Harrison Brown lamented its “poor quality” and “falsification of history.” No response from Einstein or Oppenheimer was recorded, but Leo Szilard said, “If our sin as scientists was to make and use the atomic bomb, then our punishment was to watch The Beginning or the End.”