You’re dashing around, running a bit late perhaps, and your pinky toe just happens to connect with the corner of an inanimate object that seemingly just popped up on you despite its relatively permanent and solitary position in your home.

Through watering eyes and an emanating pain that doesn’t seem natural for such a small appendage, you let out an anguished “F*CK!” It’s practically muscle memory.

And yet, most remain unaware of their favorite word’s origins, or the notion that, for many, the F-word become part of the daily lexicon due in large part to service members in World War II.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The Etymology of ‘F*ck’

The etymology of the word itself is murky, but the epithet appears to have hit its stride in the 16th century after famed English lexicographer John Florio published “A Worlde of Wordes,” an Italian-English dictionary intended to teach people these languages as they were really “f*cking” spoken.

F*ck, however, remained in the shadows of polite society largely until the onset of World War II, according to historian Tom Harper Kelly.

“One new recruit James Nichol recalled that in basic training he ‘was still very nervous of the F-word (frig being the current substitute, but I avoided that, too),’” Kelly wrote. But a sergeant in Nichol’s training company impressed the young recruit with the word’s “repetition, if not invention. I lay in my bunk one evening and counted the number of times ‘f*ck’ occurred in his conversation. It occurred every four and a half words, though I was counting mentally and might have missed some.’”

In combat, the predilection for using the expletive naturally only grew.

In “Helmet for My Pillow,” Marine Robert Leckie described the word as a “handle, a hyphen, a hyperbole; verb, noun, modifier; yes, even conjunction. It described food, fatigue, metaphysics. It stood for everything and meant nothing … one heard it from the chaplains and captains, from Pfcs and PhDs…”

The frequency in which f*ck was employed in the Marine lexicon had Leckie theorizing that any Japanese soldier who overheard an American conversation must have thought, “by measurement and numerical incidence that this little word must assuredly be the thing for which we were fighting.”

Not The King’s English

Profanity wasn’t just touted by Marines in the Pacific, however.

The F-word became such a notable part of the G.I. vocabulary that British soldiers on the Western Front identified American soldiers of the 84th Infantry Division as friendlies due to their incessant swearing. In this instance, “f*ck” happened to save their lives.

Johnny Freeman, a sergeant in the 84th, recalled being fired upon near their lines when he yelled “you f*ckers turn that thing off.”

“Is that a Yank out there?” a British soldier replied.

“Who the f*ck you think it is?” came Freeman’s retort. The American later commented, “Well, I guess the way we were swearing he knew we had to be okay, so he let us on through.”

PYling On

Some, like legendary war correspondent Ernie Pyle, lamented the linguistic crutch.

“If I hear another f*cking G.I. say ‘f*cking’ once more,” Pyle reportedly remarked, “I’ll cut my f*cking throat.”

The F-train, however, had already left the station.

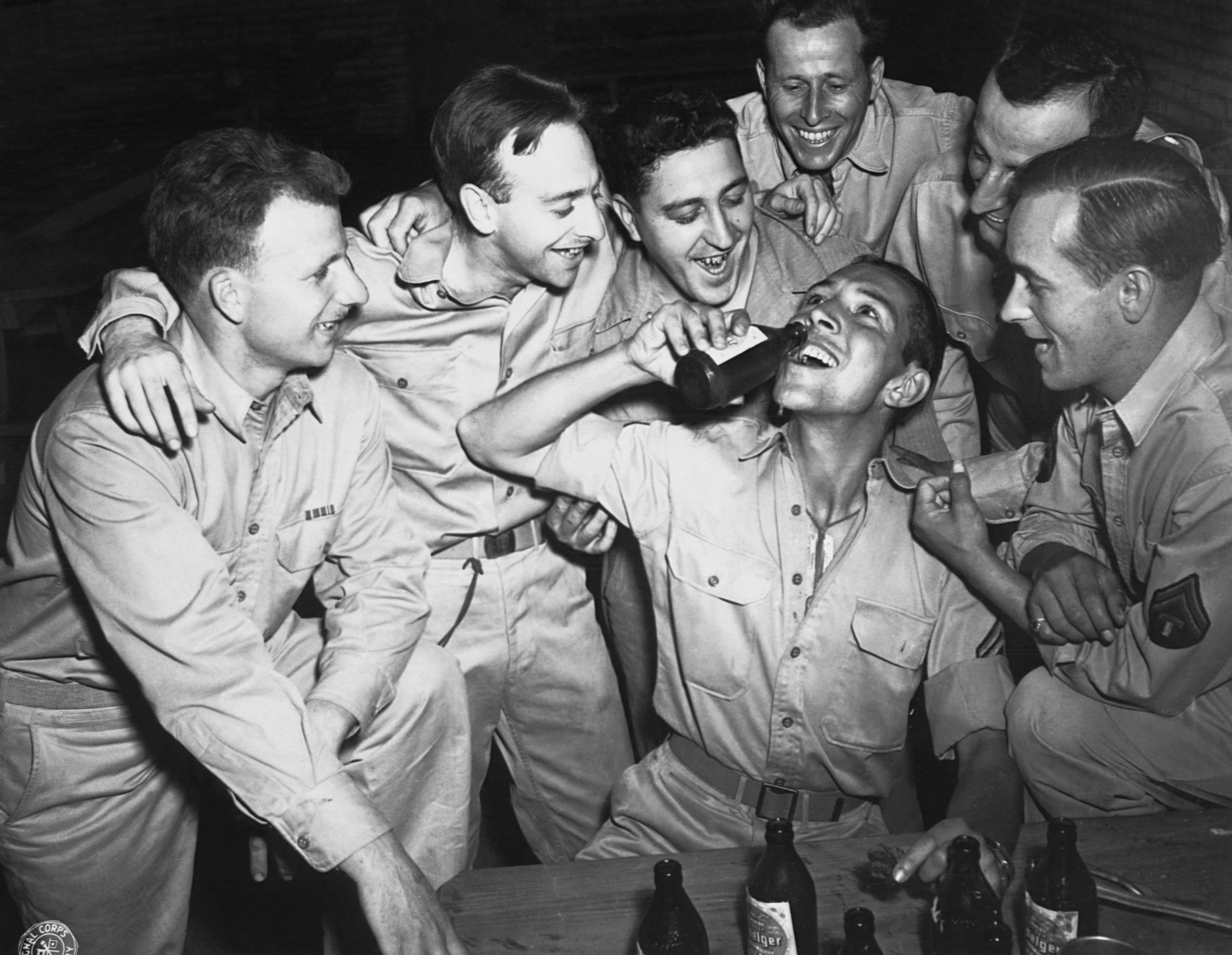

From privates all the way up to the top brass, the word’s usage was firmly inculcated into the minds and mouths of millions of American service members, so much so that it turned out to be a hard habit to kick upon returning home — eventually spreading through the civilian masses and remaining entrenched within military culture.

“I want to see them raise up on their piss-soaked hind legs and howl, ‘Jesus Christ, it’s the Goddamned Third Army again and that son-of-a-f*cking-bitch Patton,’” Gen. George Patton once quipped.

From WWII on down to the Millennial with a stubbed toe, the rampant use of ‘f*ck’ is here to stay.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.