“It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens we’ll come back for you,” Major Yoshimi Taniguchi promised a young Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda on February 28, 1945.

Taniguchi kept his promise—but it would take 29 years for him to fulfill.

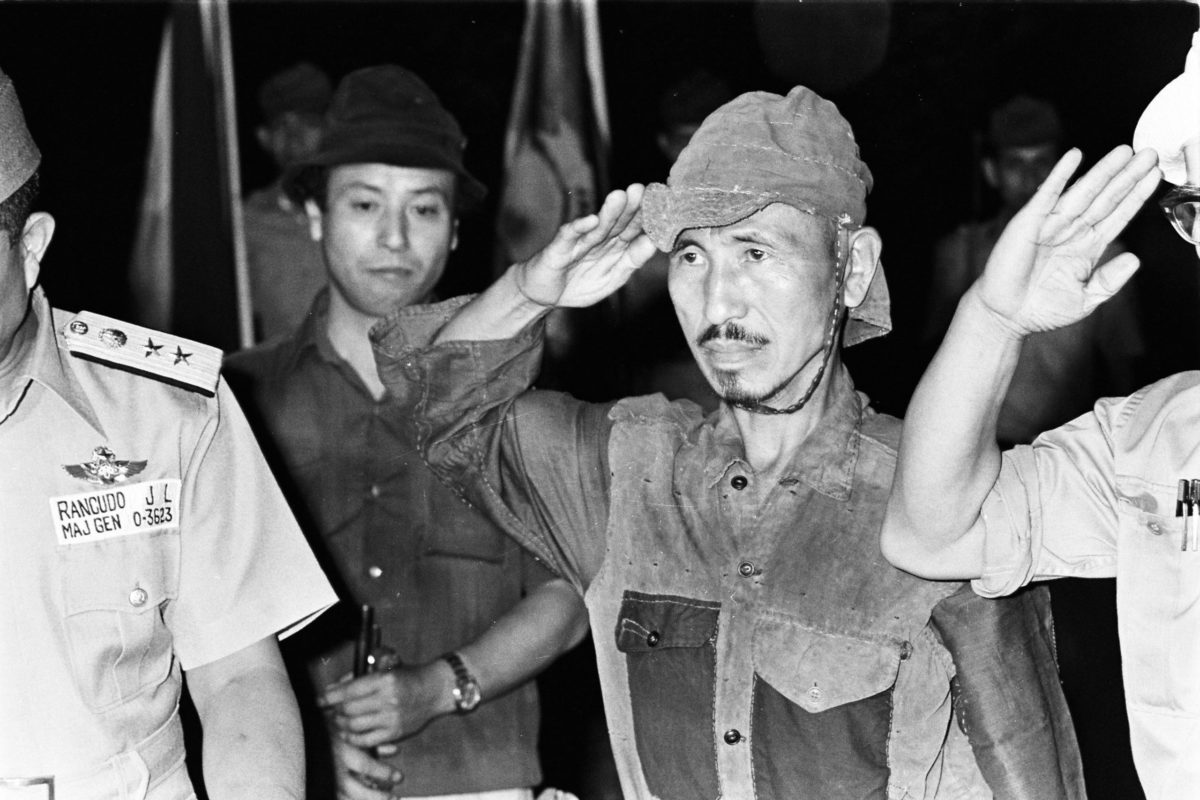

On March 9, 1974, Onoda emerged from the Philippine jungle, his Imperial Japanese uniform—worn since 1945—tattered but in remarkably good shape despite the 29 years of depravation.

Officially declared dead in 1959, Onoda was tracked down by Japanese student Norio Suzuki in February of 1974. Onoda still refused to surrender, telling Suzuki that he would not return home until he received official orders.

Suzuki returned that spring, this time flanked by a Japanese delegation, the lieutenant’s brother, and Taniguchi. After nearly three decades on the run, Onoda was convinced to capitulate.

Laying down his sword to Philippine President Ferdinand E. Marcos, a weeping Onoda became one of the last Japanese soldiers from World War II to surrender.

“I became an officer and I received an order. If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame. I am very competitive,” Onoda told ABC in 2010.

Born on March 19, 1922 in Kainan, Wakayama, Japan, Onoda joined the Japanese Army in 1942 and was singled out for specialized training at the Nakano School—Japan’s primary training center for military intelligence operations. As a student, Onoda studied guerrilla warfare, philosophy, history, martial arts, propaganda and covert operations. Such training would be key to his survival in the ensuing decades.

Onoda later recounted in his memoir No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War, that as American forces landed on Lubang, a small strategic island 93 miles southwest of Manila Bay, his commanding officer, Taniguchi, gave the young lieutenant his final order—stand and fight.

That command drove Onoda and three enlisted men into the jungles of Lubang where they engaged in guerilla warfare in the subsequent months against locals and those believed to be in cahoots with the Americans.

In the chaotic final months of the war in the Pacific, American troops encountered a near fanatical Japanese Army. When Japan officially surrendered in September of that year, Onoda, like many other Imperial soldiers, refused to believe it.

“The leaflets they dropped were filled with mistakes, so I judged it was a plot by the Americans,” he told ABC.

Surviving off of bananas, coconuts, and pilfered rice from nearby villages, Onoda and the three soldiers continued to believe that they were at war, occasionally clashing with local residents and soldiers they took to be enemy guerrillas. Over the span of several years, 30 island inhabitants were killed by the roving Japanese soldiers.

By 1974, however, Onoda was alone. “One of the enlisted men surrendered to Filipino forces in 1950, and two others were shot dead, one in 1954 and another in 1972, by island police officers searching for the renegades,” writes the New York Times.

Pardoned by President Ferdinand for the crimes committed by while still believing he was at war, the then 52-year-old soldier returned to an almost unrecognizable Japan. Although welcomed as a national hero, Onoda soon became disillusioned with the materialism and changes within the Japanese society.

The following year the former soldier moved to a Japanese colony in São Paulo, Brazil, seeking a more tranquil life raising cattle. There he married Machie Onuku, a Japanese tea-ceremony teacher. In 1984 the couple returned to Japan, founding the Onoda Nature School, a survival-skills youth camp. The pair moved back and forth from Japan and Brazil until Onoda’s death in 2014.

For many, Onoda was the last link to the old guard—a man who personified the traditional values of duty and sacrifice like the Samurais of yore.

When asked in 1974 what was going through his mind for those 29 years in the jungle, Onoda said simply, “nothing but accomplishing my duty.”