Thoughts On Hinton Rowan Helper’s Book “The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It”

Hinton Rowan Helper claimed that “an irrepressibly active desire to do something to elevate the South to an honorable and powerful position among the enlightened quarters of the globe” drove him to publish The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It. The peculiar 1857 treatise warned that Northerners were taking advantage of the slave system to make economic pawns out of their Southern brethren.

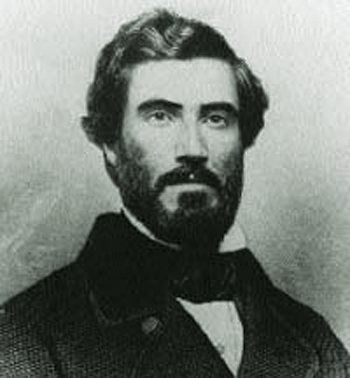

Helper was no moralizing Yankee; he was a native Southern, born into a slave-holding family in North Carolina in 1829. An adventurer and a writer, Helper had already traveled to the California gold fields and written about those experiences when he tackled Impending Crisis. He used his new book to champion the interests of the non-slaveholding Southerners who made up the majority of the region’s population. He contended that wealthy planters, whom he provocatively described as “the slave-driving oligarchy” and “chevaliers of the lash” who spent their time “lolling in…piazzas,” used the slave system to maintain power—thereby stagnating the South’s cultural and industrial evolution and hindering the fortunes of middle-class Southern farmers and businessmen.

Helper was no moralizing Yankee; he was a native Southern, born into a slave-holding family in North Carolina in 1829. An adventurer and a writer, Helper had already traveled to the California gold fields and written about those experiences when he tackled Impending Crisis. He used his new book to champion the interests of the non-slaveholding Southerners who made up the majority of the region’s population. He contended that wealthy planters, whom he provocatively described as “the slave-driving oligarchy” and “chevaliers of the lash” who spent their time “lolling in…piazzas,” used the slave system to maintain power—thereby stagnating the South’s cultural and industrial evolution and hindering the fortunes of middle-class Southern farmers and businessmen.

Helper did not think slavery was morally wrong—he in fact became a rabid white supremacist after the war—but he believed it did not provide a proper economic model to advance the South.

In 12 chapters, Helper used tables and charts to compare Southern industrial and agricultural production and wealth with the North’s, debunked the perception that the Bible sanctioned slavery and weighed literacy and educational rates of the regions. In all comparisons, the North came out on top.

Though he wrote most of the book in Baltimore, Helper had to have it printed farther North, as Maryland law forbade the printing of any tract that could entice “people of color” to aggressive action against their masters. That, he claimed, indicated slave-owners had successfully infringed on freedom of speech. To end slavery, Helper backed re-colonization of slaves to Africa, but even advocated slave-against-master violence if necessary.

Although Helper hoped his Dixie comrades would accept Impending Crisis “in a reasonable and friendly spirit” and “as an honest and faithful endeavor to treat a subject of enormous import,” he quickly became persona non grata in the South.

The “free soil” Republican Party, however, quickly saw an advantage in the book and used it as campaign propaganda for the 1860 presidential election.

Abraham Lincoln rewarded Helper by appointing him U.S. consul in Buenos Aries, a post he held from 1861 to 1866. Helper struggled after returning from Argentina, diving deeply into racial prejudice, perhaps in an effort to regain the graces of some Southerners, and concocting a failed trans-Americas railroad scheme before committing suicide in Washington, D.C., in 1909.

“The world had wrestled with him and thrown him,” the Louisville (Ky.) Courier-Journal observed in his obituary. “His mind was shattered and his heart broken. Friendless, penniless, and alone, he took his own life, and died at the age of eighty—this man who had shaken the Republic from center to circumference and who at a critical period had held and filled the center of the stage.”

Often overshadowed by Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Helper’s Impending Crisis is nonetheless one of the most interesting and influential books relating to the sectional crisis—yet most people have never heard about it. The book combines sound history and reasoning with whim, and screed against the slave-owning class—“Down with the Oligarchy!”—with pleas for the Southern middle class to accept his theory. Despite its unevenness, the volume comes off as prescient. Helper predicted nothing would really be settled until the “Flag of Freedom shall wave triumphantly alike over the valleys of Virginia and the mounds of Mississippi.”